Two recent articles in this journal bring us to the question of the meaning of “movement conservatism,” or rather, what can be “conservative” about such a movement. The first is James Matthew Wilson’s Libertarian Solutions to Communal Difficulties, and the second is Joseph Baldaccino’s Where Movement Conservatism Went Wrong–And How to Fix It.

Dr. Wilson notes, forcefully, the problems with libertarian anthropology. But he also notes the practical necessity of working with people who, like the conservatives, oppose big government. And in fact, there is in some varieties of libertarianism the same reverence for place that one finds on the Front Porch. I speak as an author whose work has been informed, in no small degree, by libertarians of this sort. However, there are also great problems. In the first place, the dominant—and most well-funded—form of libertarianism is the Neo-Austrian variety, a variety founded by a “man of 1779” who bore a peculiar hatred of religion in general and Christianity in particular.

But the greater problem is that libertarians are not opposed to big government; they are opposed to all government, and that is not the same thing. From the libertarian standpoint, if the government acts at all, it acts unjustly. The only just government is an impotent government. But as a practical matter, this does not result in limited government, but in a government that grows to gargantuan size. The libertarians fail to recognize the gargantuan forces in society that result in a demand for gargantuan government. To put it briefly, the higher the piles of capital, the thicker the walls of government necessary to protect them. As a practical matter, when the government tries to limit the influence of these gargantuan entities, the libertarian arguments are summoned forth will all the solemnity of Holy Writ. But when those same entities want a lucrative contract, a bailout, a subsidy, an exemption, or an increase in their power, the libertarians are dispatched to the corner, to stand there like errant schoolboys until they are once again summoned to do their duty. Many libertarians resent playing this assigned role, but if you want to read a defense of monopolistic and oligarchic capitalism, you will have to go to the major libertarian sites.

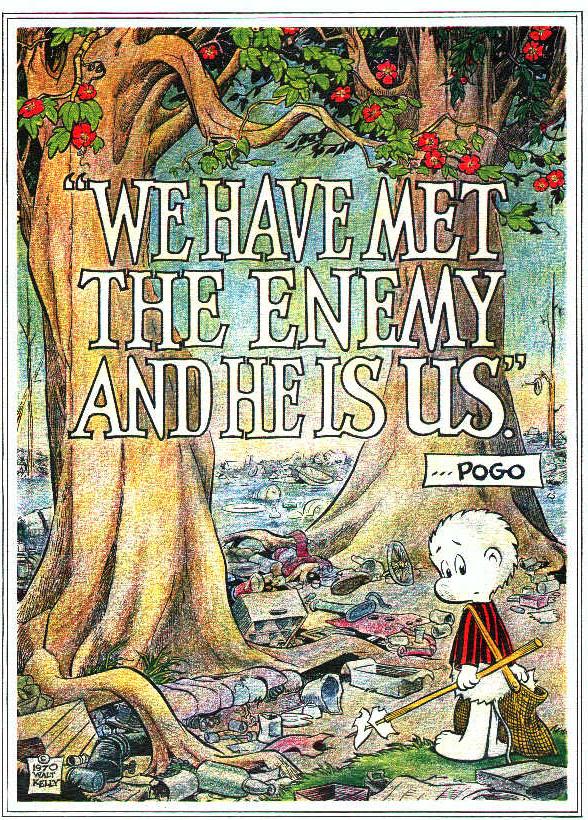

Here we can see into the conundrum that is at the heart of modern conservatism: we have tried to marry social conservatism with economic liberalism. For what we call “capitalism” is merely the Marxist epithet for what was originally called “liberalism.” Our situation then is that we keep meeting in the social realm arguments we have already conceded in the economic realm, and we wonder why our social arguments seem to carry no weight. And we are constantly surprised that what we win in elections we lose in ruling; that no matter what the regime, the results are the same: a bigger state, a larger burden, and a smaller sphere for local self-government. The state grows larger, and the access to the public purse for large corporations grows greater, while the role of the citizen is diminished. The spaces that were once occupied by small retailers and manufacturers are colonized by a few large firms, and political life becomes, more and more, the domain of powerful pressure groups quarreling over their share of the public booty. The political and economic freedom of the family shrinks until it becomes no more than a mere client of the state and the corporations.

A recent Supreme Court decision and two recent articles drive home this conundrum. The Supreme Court, which has a “conservative” majority, declared, by a 7-2 margin, that the corruption of the young is a commercial “right.” This is a court which has also determined that saying prayers in schools would be a violation of rights. Some may be impressed with the “conservative” nuances of the concurring opinions, but this does nothing to diminish the fact that the opinions were concurring.

The first article, Stonewalling Marriage, which appeared in the pages of The American Conservative, was by Justin Raimundo arguing against gay marriage. Now, Raimundo is one of my favorite libertarian authors, and he always says much that is useful and sensible. But he cannot be described as a “conservative,” a fact which he seems to acknowledge when he says “there is an effective conservative—or rather libertarian—case to be made against gay marriage.” He is certainly correct to distinguish a “libertarian” argument from “conservative” one. In this particular case, the problem with Raimundo’s arguments is that they are not so much arguments against gay marriage in particular as against marriage in general. Other than protecting children from neglect and abuse, Raimundo would not allow the law to have any role in anything that people care to call “marriage.” His arguments certainly make sense—from the standpoint of liberalism—but they are hardly arguments which a conservative can endorse. Yet, we have already conceded Raimundo’s arguments in the economic realm; how can we then turn around and deny them in the social realm?

The second article appeared in First Things. It was Robert Miller’s attack on Alisdair MacIntyre, entitled Waiting for St. Vladimir. One could fault this article for its manifold misunderstandings of economics in general and capitalism in particular, but the central point here is that Miller makes an irreducibly liberal argument for capitalism, which is the only grounds on which it can be defended. Miller argues that capitalism is an arena of pure freedom which does not have any particular goals of its own. But a conservative might critique Miller’s argument on at least three grounds. The first is that he offers us no clue of what he means by “freedom.” We can only glean from hints in the article that it means doing whatever you wish to do—that is, pure “self-interest.” But such an unrestrained pursuit of desire is not liberty, but license, and license always ends up negating liberty. Christian freedom is always oriented towards the good and is never reducible to pure “free choice.”

To take an example, one has a free choice of whether to take one’s cocaine in crystal or powdered form. One can compare the marginal utilities of both and arbitrate the differences through a price system, and proper marketing campaigns can help us to elucidate the relative benefits of each. However, while this may be a free choice, it is never a choice of freedom, since either choice leads to slavery. Licentiousness negates freedom, yet it is this licentiousness, this “freedom” from traditional moral constraints and authorities which is the essence of liberalism. We cannot endorse such licentiousness in the economic realm and not expect to meet it in the social and political realms; that is simply too much to ask.

Miller roots the “justice” of capitalism in the claim that free bargaining will give to both capital and labor what each actually earns, but there is nothing in capitalism which ensures this. Indeed, Adam Smith himself pointed out the fallacy of this theory. Success in bargaining goes to the stronger side, and Smith noted that this would always be the “Masters” and that such contracts could never ensure that labor would get its fair share of production. Contracts arbitrate power, not productivity.

Finally, we can note that Miller asserts that capitalism has no end in itself, but only provides a mechanism for the pursuit of ends that individuals choose for themselves. So if one wants to pursue the sane and limited ends of what Aristotle and Aquinas understood by “economics,” the proper provisioning of the household and the common goods of society, and another chooses to pursue the infinite acquisition of money and purely individualistic ends, capitalism does not discriminate between them. But surely, there are no “neutral” systems. Institutions reward some pursuits and punish others, and those who pursue insane and infinite ends (and insane because they are infinite) will tend to crush those who pursue sane and limited ends. And this is precisely what we see in the market today. Moreover, firms interested only in the infinite pursuit of wealth and guided only by the “logic” of self-interest will not be able to resist the temptations of “regulatory capture,” that is, of capturing the mechanisms of the state and using them to their private ends; of treating the public purse as a private preserve. Any supposed “market discipline” will be undermined by sheer political power.

But perhaps the real problem with the article may be simply the condescending tone, a tone that begins with the title, which seems to accuse MacIntyre of being a closet commie. And what has MacIntyre done to draw this accusation? He has dared to apply the moral law to the material order; he refuses to divorce ethics and economics. But this contradicts Miller’s claim that capitalism is a “morally neutral” playing field, and Miller instructs MacIntyre as he would an errant child, as if the (arguably) foremost conservative philosopher had no knowledge of such things. Indeed, any attempt to join the moral and material realms is to be seen as a case of creeping communism. Not that ethics are to be excluded entirely, but they enter the economic realm only as a matter of private choice, not public policy. As a private choice, ethics have the same status as any other consumer choice, take it or leave it, as one’s “utility” dictates.

However, this claim of “moral neutrality” hides a practical claim of moral superiority. Most of our actions are, in some sense “economic,” and all of our actions are material; even prayer requires the expenditure of energy, an energy that will have to be replaced, most likely in the realm of economic exchanges. This realm of exchanges is to be guided, according to the predominant theory, by the pure pursuit of profit. Now, since morality is about the realm of actions, and much of this action takes place in the economic realm, then the unavoidable conclusion is that most of our actions should be guided by the pursuit of profit, or at least of self-interest.

The “incarnation” of this division of ethics and economics is given, I think, by the Fox media empire. There, consistent support is given to “family values” on the news channels, while doing everything it can to destroy the family on its “entertainment” channels. The moral message is clear: “Morals are great as a personal or political issue, but they must never be allowed to interfere with the pursuit of profit. Hey, this is just business, and people can make their own choices; we just offer products in a morally neutral realm.”

All this, I think, is the answer to the question of why “movement conservatism” doesn’t work. The reason is that there is no conservative movement, only a movement in which the concerns of conservatism are subordinated to the needs of economic liberalism. This will never work, or at least, it won’t work for conservatives; they will be forever wondering why they can run but cannot rule. They will always wonder why, after getting their friends into office, bad things happen, the same bad things, more or less, that happen when their friends don’t win. The same things happen because the same ideas rule, merely in left- and right-wing variants, which really aren’t all that variant.

All that being said, I would certainly l like to work with such people as Justin Raimundo or Robert Miller, when the occasion arises. But we cannot work as junior partners, lending our efforts to the victory but sharing nothing of the spoils. That is to say, I don’t mind working with them; I just don’t want to work for them. So how does a group gain influence in the politics of a democracy? Such a polity tends to be built around factions, and two collections of factions tend to dominate the system. In America, these coalitions of factions are the Democratic and Republican Parties. In such a structure, a group gains influence by the credible threat to withhold support. Take the case of the Tea Party. Although a minority of the Republican Party, they seem to control it right now. Why? Because they have let it be known that they are not “real” Republicans, and that their support of the Party is contingent on the Party’s good behavior. That means that the Party must be continually “bidding” for their support. Say what you like about the legislative agenda of the Tea Party, they have certainly played their political cards right.

We can do no less. Of course, it would help if there were more of us, and if we had more awareness of our own distinctive character. It may be, in the current circumstances, that we can do nothing, save what a remnant always does: wait, pray, prepare; the moment will come. But what we cannot do is both maintain our conservative identity and exist as a mere adjunct to economic liberalism.

This brings us to the problem of the Tea Party. One certainly applauds their goal of a smaller government, and one must certainly sympathize with their anger and passion. But passion is never enough; one needs some understanding as well. In truth, we have seen this movie before, and we know how it ends. We saw it in 1980, and again in 1994, and again in 2000. “But this time is different,” you might say. But that is what they said all the other times. And all the other times, the passion dissipates and the members of the movement who got into office drift into the routine of party politics, seeking lucrative committee assignments, and retirement into jobs as lobbyists or consultants for the industries they were supposed to control.

The ideology of the Tea Party, insofar as I can locate any, is to assert an individualism against the all-powerful state. But as Patrick Deneen points out, individualism is not something opposed to statism, but rather its prerequisite; the state cannot be everything until everything else is nothing. Individualism erodes every other institution, leaving nothing but the state. You end up with a situation where any attempt to assert a common good gets labeled as communism, as Miller does with MacIntyre.

One final exemplar of the problem. Phillip Blond recently made a tour of the East Coast to garner support for an American equivalent to his “Red Tory” movement among “movement conservatives.” I do not know the outcome of these talks, or how much support he was able to garner. But I suspect that Grover Norquist’s response was typical; he particularly objected to Blond’s criticism of the free market. “There’s zero interest in that in the U.S. – given the regulatory and spending explosion the last 20 years, there’s no sense that there’s runaway market liberalism.” Well, perhaps. Maybe the problem with the markets is a lack of liberalism, but it is not even regarded as odd that a “conservative” activist will root his case in liberal arguments. And I find it interesting that Grover’s critique of Blond is that he is insufficiently liberal. At the same time, Mr. Norquist has been disappointed in the past that his group helps to elect conservative candidates, but only ends up with liberal government. But what Mr. Norquist doesn’t seem to realize is that in any argument between a liberal and a liberal, the liberal will win every time.

52 comments

john

If you want staunch localism, with extended family interaction you can find it in WV, which is not the old south nor the north but a state in which we stand by our motto of montani semper liberi. It is not what peopel assume a group of rugged individualists, but rather a large family, interdependent, fighting occasionally like brothers and sisters but turning on mass at anyone who attacks the family.

HFCS

I don’t want to even finish the comments. Quite frankly I’m embarrassed and disgusted by JonF. Embarrassed and disgusted to know he is Orthodox. I don’t appreciate the haughty and condescending denigration of my heritage and ancestry. I’m not apologizing for a damn thing about being a Southerner.

JonF

Re: As I wrote on the other thread, rejecting the entire Southern tradition because of slavery is akin to rejecting the entire Russian Orthodox tradition because of serfdom.

It’s impossible to separate slavery and its attendant racism from the Old South. The South was defined by its peculiar institution, as much as ancient Rome was by its legions or the ancient Hebrews by the Law.

That’s not true of Russia and serfdom: it developed remarkably late, always had its critics and wa abnadoned peacefully because even the most conservative elite realized it was not working and was contrary as well to Christian ethics.

Russia (for a couple of centuries) was a society with serfs. The South was a slave society.

As Anymouse suggests we might do better to look back medieval Christendom for inspiration on how men ought live with one foot in the Kingdom of Heaven and the other foot in a bunch of badly flawed earthly kingdoms.

Anymouse

One way to evade some of this is to go back to the Medieval Tradition, but fewer people remember that or are willing to see it as relevant. However, is it any less relevant than the Old South?

Rob G

“Genovese is as harshly critical of the Southern plantocracy as I have been here.”

Yes, and I agree with him. The difference is, he sees the value of what remains of the Southern Tradition sans slavery, you do not. Hell, even W. E. B. DuBois was able to see it.

As I wrote on the other thread, rejecting the entire Southern tradition because of slavery is akin to rejecting the entire Russian Orthodox tradition because of serfdom.

“The Old South is dead, but nevertheless whenever it is mentioned it’s suddenly 1860 again and we have to make our ritual denunciations of slavery, everyone associated with slavery, everything associated with slavery, and everything associated with everyone who was associated at any point in the past with slavery.”

Indeed. In fact, I’ve thought about making a little laminated card that simply says “I”m against slavery” to carry with me when I get into these discussions with friends or acquaintances. I can flash it every 5 minutes or so, just to reassure them, without having to say anything.

Matt Weber

The Old South is dead, but nevertheless whenever it is mentioned it’s suddenly 1860 again and we have to make our ritual denunciations of slavery, everyone associated with slavery, everything associated with slavery, and everything associated with everyone who was associated at any point in the past with slavery. It’s all so boring and predictable. Slavery is dead and gone and never coming back. The Southern tradition has its problems, which in the modern day include an absurd cheerleading for the warfare state, but in terms of domestic government expansion the South is about the only place left where there is serious opposition. If Northern decentralists will not work with Southern decentralists because of the icky ickiness of slavery, then we might as well just admit defeat and get it over with.

Anymouse

“And at the end of the day it’s still 2011 and the Old South, the Old North and the Old West are still as dead as Alexander the Great.”

Very true.

JonF

Genovese is as harshly critical of the Southern plantocracy as I have been here. In recent years he and his wife have found Christ via Catholicism (and good for them) and adopted a more Burkean perspective, replacing his earlier Marxism (and again, good for him).

I have never been a Marxist; my critique of the excesses of wealth and power has always been grounded in a Christian humanism tethered to the Gospel. You will not find me repenting earlier atheistic follies by suddenly praising massa on his horse, or his modern-day equivalent in corporate boardrooms and lobbyist firms.

And at the end of the day it’s still 2011 and the Old South, the Old North and the Old West are still as dead as Alexander the Great.

Rob G

Read Genovese, then report back.

JonF

Hmm, is the “no true Southerner” fallacy the American version of “no true Scotsman”.

To be fair here, the South some of you are pining for is as moribund as the small town North I am rhapsodizing about, “for all have sinned and come short of the glory of God”.

Rob G

“They’re more Republican than Southern, and expected given the history and origins of the Republican party.”

Exactly. To paraphrase M.E. Bradford, just because one is a conservative from the South does not mean he is a Southern conservative. A true Southern conservative will have serious disagreements with at very least the pro-corporate capitalist nature of the GOP. Southern conservatism has always been wary of the centralizing aspect of both government and corporate power.

pb

“But I see that it is the paternalistic politicians of the South– the Gingriches and Perrys and Scotts and DeMints– who are quickest to do their bidding, and provide them ideological cover under the Orwellian notion that “liberty” is the freedom to oppress others.”

They’re more Republican than Southern, and expected given the history and origins of the Republican party.

JonF

Rob G, you and I differ on the source of the trouble. Though it does seem we both realize there’s problem. For me however the problem is the Southern tradition of Big Government keeping the peons in chains (metaphorical or otherwise), while New England is the tradition of prgamatic small town democracy as epitomized by the town meeting.

Of course our Overclass is very much delocalized: neither Southern nor Northern nor Western– in fact, not even particularly American.. But I see that it is the paternalistic politicians of the South– the Gingriches and Perrys and Scotts and DeMints– who are quickest to do their bidding, and provide them ideological cover under the Orwellian notion that “liberty” is the freedom to oppress others.

Rob G

“the oligarchial faction of our nation (which tradition has the strongest roots in the South) is gradually turning the rest of into a 21st century version of serfs.”

No, it’s the plutocratical faction of our nation, which has its strongest roots in New England, that’s re-feudalizing us. And any number of Southern conservatives have protested loud and long against it.

Anymouse

“I was praising the small town societies of the North and the West, (New England town meetings, barn raisings, that sort of thing), not the crusading do-goodism of the Victorian upper classes.”

Understandable. I think we agree more than we thought.

Maughold

“Yankee Progressive Meddling Do-Goodism has exactly zilch to do with Christ, neither back in the CW era nor today.”

Rob G, this gets my vote for quote of the week. You inspired me to go sit on my front porch, sip Bourbon (neat), and whistle Dixie.

Not that I need much encouragement for any of those things.

And by the way, yes – Genovese is key. Glory to God for all things!

JonF

At the end of the day no slave-based society can be a limited govermment society. It takes unrestrained power to keep people in bondage.

And to clarify my original point (lost in the fracas), I was praising the small town societies of the North and the West, (New England town meetings, barn raisings, that sort of thing), not the crusading do-goodism of the Victorian upper classes.

Anymouse

Indeed, those were serious problems and they brought us into a Civil War. But I don’t think the agenda of those in New England like Horace Mann was any less destructive or dangerous.

JonF

Re: No one wants to re-institute it, so who cares?

No one wants to restore chattel slavery, but the oligarchial faction of our nation (which tradition has the strongest roots in the South) is gradually turning the rest of into a 21st century version of serfs.

Re: the Old South still takes the cake for having the least power in the hands of the Urban Middle Class.

And the most power in the hands of a small band of oligarchs who eventually became corrupted by it, not unlike alcoholics or drug addicts willing to fight to death to maintain their habit.

Sorry, but I cannot admire oligarchy in any form. That corruption doomed other great nations (the Greeks and Romans come to mind) and the inevitable reaction to it, in civil war and revolution, is everything the devils could wish for.

Rob G

“I am an Orthodox Christian (why do you immediately assume I am an atheist?”

I’m not assuming that at all. What I am saying is that Yankee Progressive Meddling Do-Goodism has exactly zilch to do with Christ, neither back in the CW era nor today.

“Slavery is a red herring. No one wants to re-institute it, so who cares? The Southern tradition, albeit much diminished now, has been the one force that has held back the march of centralization in this country. But because it was involved with slavery 150 years ago, we must spurn it.”

Yes, this is like saying that because of the Inquisition we must reject the good that the Roman Catholic Church has done , or perhaps more to the point, the Russian Orthodox Church because it once owned serfs.

“Given your lack of objectivity you should just avoid discussing the South.”

Or at least take a look at a scholar or two who are strongly anti-slavery, yet see the elements of value in the Old South. Genovese in “The Southern Tradition,” for instance, or Christopher Duncan’s “Fugitive Theory.”

T. Chan

“The Constitution also did not enjoin slavery on any state (despite claims to the contrary by some leftwing critics that the Constitution defended and espoused slavery). The matter was left up state sovereignty, and when slaves ran away in the early years of the Republic no one pretended that free states had any duty to return them in defiance of their own laws. Full, faith and credit no more applies here than it does to marriage laws, or to laws defining what sorts of exotic animals one may keep: if Georgia lets you keep pythons, but Michigan does not, then you you have no expectation of being able to keep that python if you relocate to Michigan. (And this is the last website I would expect a one-size-fits-all definition of any laws to be advised upon us!).”

Irrelevant to the points about the Fugitive Slave Act. What is relevant is Article 4, Section 2 of the United States Constitution.

“Please stop defending the indefensible. It just damages your own cause– which is localism, after all, not the vindication of the antebellum South.”

Who is defending the indefensible? If anyone is in danger of discrediting himself it’s you with your admitted bias, which leads you to find inconsistency where there is none. That’s all I am pointing out. Given your lack of objectivity you should just avoid discussing the South.

Matt Weber

Slavery is a red herring. No one wants to re-institute it, so who cares? The Southern tradition, albeit much diminished now, has been the one force that has held back the march of centralization in this country. But because it was involved with slavery 150 years ago, we must spurn it. Well, since we can’t go back and eliminate slavery from history, I guess we’ll just have to live with the uber-state.

Anymouse

I agree that is important to fix problems but I feel that the fixes settled upon by the North and West, and the South as well if one looks at the origin of racism in the 1600’s, were damaging solutions. I do think we need modern transportation and weapons technology in this country, and I have nothing against IBM mainframes or Linux PC’s. But I do feel that the rise of the modern urban environment and the urban middle class has been a root cause of much of our social dysfunction. As a result I have a hard time sympathizing with the parts of the country most responsible for giving rise to those things. I have also probably concentrated too deeply on the South in my historical research, but the Old South still takes the cake for having the least power in the hands of the Urban Middle Class. I also admire the Japanese Empire to some extent as well because they also had a rural society that managed to moderate the influence of anti masturbation hysterics, prohibitionists, radical protestants and other disrupter’s of traditional society.

JonF

Anymouse,

There’s nothing wrong with reform, is there, if it carried out locally? After all, sometimes things are well and truly messed up and they do need to be fixed. Why shouldn’t localities be praised for carrying out those reforms? The cliche that the states are Laboratories of Democracy applies here too. The principle here is that if a reform works in some places, others will see it and say, Hey that works, let’s try it. But if it fails, well, at least it didn’t fail on a nationwide scale. It’s precisely this wedding of can-do let’s-fix-it sprit that I find admirable in the North and the West.

And in the end “Change or Die” is a basic law of nature. Changeless Lothlorien is a sentimental daydream, as even Tolkien recognized by having his Elves ultimately depart time-bound Middle Earth for a hidden realm ruled by being born outside of Time.

JonF

The Constitution also did not enjoin slavery on any state (despite claims to the contrary by some leftwing critics that the Constitution defended and espoused slavery). The matter was left up state sovereignty, and when slaves ran away in the early years of the Republic no one pretended that free states had any duty to return them in defiance of their own laws. Full, faith and credit no more applies here than it does to marriage laws, or to laws defining what sorts of exotic animals one may keep: if Georgia lets you keep pythons, but Michigan does not, then you you have no expectation of being able to keep that python if you relocate to Michigan. (And this is the last website I would expect a one-size-fits-all definition of any laws to be advised upon us!).

George Washington himself lost at least one of his slaves to freedom in Pennsylvania. He did not send federal troops after her, nor sue Pennsylvania in court for her return. He did write her letters (apparently she could read) complaining of her flight and reminding her how well she had been treated at Mt Vernon, inviting her to return– though she did not.

Please stop defending the indefensible. It just damages your own cause– which is localism, after all, not the vindication of the antebellum South.

T. Chan

Like it or not, the Constitution did not outlaw slavery, and to enforce property rights under the Constitution did not violate the Constitution or state sovereignty.

T. Chan

“That’s not what the old South was about at all. Don’t fall for the old propaganda: it was much a lie as anything Stalin ever concoted. Whenever the South had sufficient power it rolled right over other states’ sovereign laws. Again: see the Fugitive Slave Laws, which basically instructed all the free states that they were bound to enforce the slave states’ laws on that subject.”

“Full faith and credit” and the other relevant constitutional principles regarding property under the Constitution. This is not to say that human beings should be considered property, just pointing out that it’s not inconsistent with the contemporary understanding of state sovereignty and the federal union.

Anymouse

“There most certainly were prohibitionists in the South. Both the Baptist and Methodist Churches were teetotalers who supported the ban– and some areas of the South remained dry well after 1933. The South also has a rightwing version of the Social Gospel,”

I acknowledge that, but that was largely after the Civil War and the rise of the New South, which had little to do with the Old South except the racism. Maine was the first state to engage in Prohibition of alcohol by a constitutional amendment. The South did not seriously pick up on Prohibition until the Progressive era. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohibition_in_the_United_States#History

“If you are looking for localism, why not look to the small town traditions of New England and the upper Midwest, or the frontier traditions or the American West?”

Those are to be admired, but I admire the Old South’s tendency to explicitly reject the trappings of Modernity such as the aforementioned social reform movements that those regions embraced. The dominance of a rural Elite was an important part of that, and is part of the reason why I do not trust an urban middle class as our leadership.

Human Dignity

You don’t get it. Corporations only have power because the Government gives them benefits (e.g., limited liability and regulations designed to help big corporations crush little ones). If you want to limit corporate power, then limit the benefits that government gives corporations.

JonF

Re: What was that I wrote on the other post about humanitarianism without Christ leading to the gas chambers?

I am an Orthodox Christian (why do you immediately assume I am an atheist?). My basic reflex is toward pacifism, though I know that in this fallen world war is sometimes the only option.

Yes, I was rather irrascible last night. But those feelings I expressed were genuine: I despise Old Dixe and everything it stood for, including its latter-day zombie influence on American politics.

If you are looking for localism, why not look to the small town traditions of New England and the upper Midwest, or the frontier traditions or the American West? The former especially are much less fraught with problematic history.

Re: No prohibitionists, a weak Social Gospel movement, and a Strong Belief in the dignity of one’s family.

There most certainly were prohibitionists in the South. Both the Baptist and Methodist Churches were teetotalers who supported the ban– and some areas of the South remained dry well after 1933. The South also has a rightwing version of the Social Gospel, and belief in the family can be found anywhere; nothing uniquely Southern about it.

Henry Wirz was hanged after due process for war crimes. Read the history of Andersonville; though warning: it’s nauseating. And my suggestion is that perhaps some of the Southern leaders ought have been hanged (also after due process) for treason and rebellion. They created a war in which half a million Americans died, unforced and unnecessary. Comparing that to the Katyn massacre is frankly absurd, a rightwing version of the crocodile tears shed over the Rosenbergs, or the “Free Mumia” balderdash.

Preston Brooks’ crime demonstrates the evils of an honor/shame culture where morality is replaced with social standing. We see the same thing in today’s lower class environs where “dissing” someone can get you killed. Or in the lands of Islam for that matter. I’d rather have the ethics of virtue, thank you.

Anymouse

The Old South had a great and evil mark against it: a brutal and racist slavery. Other than that it had many things to recommend it over the North: No prohibitionists, a weak Social Gospel movement, and a Strong Belief in the dignity of one’s family. Whatever one says about Preston Brooks beating of Sumner it demonstrates an attachment to ones extended family that was rapidly being eroded in the North by public schooling, middle class adolescence and the nuclear family.

Rob G

“…I rather wish General Sherman had had a bit more time for arson, and that Capt. Wirz had been sent to his dark reward with a good deal more company doing the devil’s dance beside him.”

What was that I wrote on the other post about humanitarianism without Christ leading to the gas chambers? Apparently it leads also to the validation of war against civilians and to wishes for some American equivalent of the Katyn Massacre.

This, friends, is why liberalism is tyrannical.

JonF

Re: The desire for “small government” is not incompatible with a doctrine of state sovereignty

That’s not what the old South was about at all. Don’t fall for the old propaganda: it was much a lie as anything Stalin ever concoted. Whenever the South had sufficient power it rolled right over other states’ sovereign laws. Again: see the Fugitive Slave Laws, which basically instructed all the free states that they were bound to enforce the slave states’ laws on that subject. Also there’s the matter of the Mexican War wherein, at the South’s behest for more Sklavenraum we grabbed a bunch of land from a neighhbor who had really done nothing in particular to merit that action.

I’m the proud great-great-grandson on two men who gave their lives to defeat that evil wanna-be empire and when I see how old Dixie has risen from the grave and now haunts our body politic like the Curse of Dracula, I rather wish General Sherman had had a bit more time for arson, and that Capt. Wirz had been sent to his dark reward with a good deal more company doing the devil’s dance beside him.

Albert

I always look forward to Mr. Medaille’s posts. Thanks again. It’s a fine summary of our situation and what led to it.

I do agree with the minor criticism that “no government” is descriptive of anarchism rather libertarianism; it’s a small point, but it’d be wise not to give detractors any room to complain.

Rob G

“Let’s remember that the Southern tradition is stained indeliably with a very great evil and should be suspect at its core for that reason.”

Actually, no. The pertinent aspects of Southern conservatism have absolutely nothing to do with slavery. The fact that such a stalwart anti-slavery man as Genovese is is able to see this (without, by the way, ignoring the problem of racism in the South) speaks to the value of that particular tradition.

pb

“Calhoun and his ilk complained about a government they did not control; when they controlled govermments (as they did in their own states) they used government for their own ends as brutally as any fascist or comissar. Nor did they have a problem using the Federal Government when they could to trample on the rights of people in localities distant from their own. See: Fugitive Slave Act.”

“Seriously?” The desire for “small government” is not incompatible with a doctrine of state sovereignty, and is entirely consistent with that tradition of American federalism. Similarly, the “use of the Federal Government” is consistent with the Constitution.

JonF

Let’s remember that the Southern tradition is stained indeliably with a very great evil and should be suspect at its core for that reason.

Also, the old South was no friend to small government. Calhoun and his ilk complained about a government they did not control; when they controlled govermments (as they did in their own states) they used government for their own ends as brutally as any fascist or comissar. Nor did they have a problem using the Federal Government when they could to trample on the rights of people in localities distant from their own. See: Fugitive Slave Act.

John Médaille

Stephen, I think you have grasped the nettle when you say ” the lobbyists and their puppets in DC won’t let it.” Exactly. They won’t let them do anything that limits the power of government, save and except when that power threatens to interfere with corporate power. So the corporation is the prior problem. But by definition, he cannot move against the corporations. It’s a lose-lose proposition.

The bailout is a perfect example of the problem. Yes, Paul opposed the bailouts, as I did. But he had nothing else to suggest, other than “let the market take its course.” That would have been a disaster; the banks really would have failed, and there really would have been rioting and bankruptcy all around. These banks held 35% of all our deposits, and if they failed, the regionals would not be far behind. Bush did the wrong thing, but he was right to do some thing. What they did is reward the banks for their failures; but the right answer isn’t to let the banking system–and the country with it–fail.

Rob, I agree, there is a long traditon of real conservatism. De Tocqueville writes of what is an authentically conservative nation. And along with Southern agrarianism, there is a northern and Western tradition as well. Thanks for the link to Skidelsky; that is very good.

Rob G

“If conservatism is apriori undermined by its wedding to economic liberalism, have there been conservatives in the U.S. since the Tory’s of George III?”

One place to look is at the Southern conservatism which was given a voice by the 12 Southerners of ‘I’ll Take My Stand,’ then was continued through the work of Richard Weaver and the scholars influenced by him, incl. Russell Kirk. See Weaver’s ‘Ideas Have Consequences’ and Eugene Genovese’s ‘The Southern Tradition.’ It is entirely possible to support business and what might be called “small market capitalism” while rejecting corporate/industrial/finance mega-capitalism.

That economic liberalism is in some sense tainted at the source:

http://www.firstthings.com/article/2011/05/the-emancipation-of-avarice

Stephen

Mr. Medaille, you say,

“Yes, like all libertarians he has an excellent critique of crony capitalism. But where is the legislative program to limit it? Here he is caught in his own trap: for the government to do something about it, it would have to do something, and having the government do things is excluded by the theory.”

His legislative program to limit crony capitalism is: 1) vote against bailouts and the other sweetheart deals for banks and corporations, 2) reverse monetary policies designed to devalue the currency (which reduces the effective value of debts), and (3) abolish the Federal Reserve, which uses tax funds to give cheap loans to various large corporations. I’m not sure that I agree with (3), but taken all together, these proposals are a serious approach towards ending “too big to fail” and crony capitalism in general.

Perhaps you think that we have to first reduce the power of corporations, and then downsize the federal government. As long as the federal gov’t remains such a powerful institution, that’s not going to happen: the lobbyists and their puppets in DC won’t let it. On the other hand, if we stop bailing out car companies and investment banks and let the next failing firms go through the normal process of bankruptcy, we’ll make it clear to those companies that they have to assume the risk for their behavior, and can’t rely on the citizenry to pay for their mistakes.

Marchmaine

Is MacIntyre’s response available to the public yet?

Charles

“But the greater problem is that libertarians are not opposed to big government; they are opposed to all government, and that is not the same thing. From the libertarian standpoint, if the government acts at all, it acts unjustly.”

Wrong, and wrong. Stopped reading here, and feel pretty good about not wasting my time on a ridiculous straw man article.

Hugh

“Yes, like all libertarians he has an excellent critique of crony capitalism. But where is the legislative program to limit it? Here he is caught in his own trap: for the government to do something about it, it would have to do something, and having the government do things is excluded by the theory.”

If “doing something about it” involves the government limiting its activities, then I don’t think that type of action is excluded by the theory.

If conservatism is apriori undermined by its wedding to economic liberalism, have there been conservatives in the U.S. since the Tory’s of George III? Also, what then is the definition of “conservative?”

Leonard W. Grotenrath Jr.

Mr. Medaille,

Have you ever had occasion to speak with MacIntyre about distributism? His response to Robert Miller via letter in First Things, as well as other aspects of his political philosophy seem to be compatible with a distributist-like socio-political order. Thanks for another excellent post.

MacIntyre will be among the presenters at this year’s conference at Notre Dame sponsored by the Center for Ethics and Culture.

John Médaille

Stephen, I think Ron Paul is exactly what I am talking about. Yes, like all libertarians he has an excellent critique of crony capitalism. But where is the legislative program to limit it? Here he is caught in his own trap: for the government to do something about it, it would have to do something, and having the government do things is excluded by the theory. There are no transitional states permitted, nor any action legitimized by the current situation. So at a practical level, you just sit around and wait for the corporations to whither away. I like Ron Paul, and I think he is a man of integrity, but I don’t think he really has anything concrete to offer. At the level of action, the theory nullifies itself.

And yes, there are differences in Libertarian theories, but the major difference comes down to this: the anarchists say the gov’t should do nothing and the Austrians say the gov’t should do nothing but protect property and contract. At the level of theory, this is an important distinction, but at the level of practice, it doesn’t amount to much. “Protecting property” turns out to be an expensive affair, requiring armies, courts, police, regulations, and the whole panoply of the modern state. And it doesn’t help that they never bother to to define property and its origins, so the theory ends up as just the state protection of whatever property relations are in effect.

The anarchists limit property to use, which is closer to the Christian (or at least Patristic) understanding, but they have no means to protect it. Or rather, they believe that such means will arise spontaneously at the local level, without the aid of government. That’s a charming belief, but I suspect what would arise “spontaneously” is warlord-ism, which would smother any rival before it could get properly started.

Rob G

Too often, though, it seems that libertarians and conservatives of a libertarian bent blame the state for corporate sins, as if the only reason that corporations do bad things is because the state enables them somehow. The unspoken assumption is that if there are ever injustices in the economy, they are always due to state intervention of some sort. Thus, “crony capitalism” is seen to have little or nothing to do with the corporations seeking after cronyist favors.

JonF

Re: I think there is an unstated disagreement among folks here at FPR concerning which comes first: economic or political centralization.

I vote for economic centralization. If you look at history, both in the US and abroad, you find industrialization and globalization happening first, then the growth of the state in response to some manner of crisis sparked by the economic trends.

Stephen

Mr. Medaille,

You say,

“[T]he greater problem is that libertarians are not opposed to big government; they are opposed to all government, and that is not the same thing. From the libertarian standpoint, if the government acts at all, it acts unjustly.”

What you are describing here is anarchism, not libertarianism. The two are sometimes related (e.g. Rothbard), but are not identical. Perhaps this is done for rhetorical effect, but it diminishes the credibility of your critique.

A second mistake is when you say,

“[W]hen those same entities [large corporations] want a lucrative contract, a bailout, a subsidy, an exemption, or an increase in their power, the libertarians are dispatched to the corner, to stand there like errant schoolboys until they are once again summoned to do their duty. Many libertarians resent playing this assigned role, but if you want to read a defense of monopolistic and oligarchic capitalism, you will have to go to the major libertarian sites.”

I certainly prefer the distributist critique of crony capitalism (such as Chesterton and Belloc’s), but in our country, the strongest critiques of the bailouts and corporate giveaways came from libertarian leaning folks like Ron Paul. Pinning crony capitalism on libertarians is unfair. I know some would be inclined to say that libertarianism makes a strong national government inevitable by breaking down all social institutions, etc, etc, but please keep in mind that crony capitalism has flourished most in collectivist societies, not individualist ones.

Perhaps this is a bit of an aside, but I think there is an unstated disagreement among folks here at FPR concerning which comes first: economic or political centralization. This is an important question, for it gives us some clue as to whether using a powerful national government to break the power of large corporations is a good strategy for porcher ends, or whether a more libertarian approach is better. Hopefully at some point a contributor might take up this question specifically.

Rob G

The Right needs to learn that social libertinism and economic libertinism spring from the same poisoned root — a de-Christianized individualism. As Wendell Berry has written, you can’t take greed off the list of sins then presume to put some sort of limit on it. You can’t tell people they can be greedy “up to a point,” any more than you can tell people they can be lustful “up to a point.”

JonF

Re: This is a court which has also determined that saying prayers in schools would be a violation of rights.

This is false. Anyone may pray in a school as long as they are not disruptive. And since prayers can be said without voicing them, there’s no way for schools to prevent such prayers, absent telepathy.

What is forbidden are state-mandated prayers. And I have to say I wonder at people who criticize Big Govermment one minute and then opine that the govermment is competent to define how we should pray. I can think of nothing, not even the details of the marriage bed, that is more a matter of private determination. Moreover, given that we are religiously diverse society, even down to the neighborhood level, any government-written prayer will be some horrid cludge of theological compromises that sterilize it to nullity. Hardly pleasing to God, and perhaps rather directing us into the ways of those Pharisees who loved to pray in public for public praise, about whom Jesus had no high opinon.

Comments are closed.