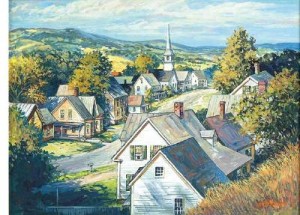

Cold Spring, NY. Leopold Kohr, the author of the great classic, The Breakdown of Nations, once said that his approach to the world–in favor of smaller nations, smaller institutions, smaller associations–was due to his having been born in a small village, Obendorf, just outside of Salzburg, Austria. When your childhood is spent within limits, he used to say, where you get to know a good number of people well and also a lot of people no closer than to say “hello” to, you have some approximate experience of how humans lived for many eons before anyone ever thought of cities.

There is much murkiness here, but the general anthropological opinion is that the original African Homo sapiens settlements consisted of bands of between 25 and 50 people, within tribes that might have been between 500 and 1,000, and this is how we lived for at least 250,000 years. It is, as they now say, encoded in our genes. “the social organization based on the hunter-gatherer ways of life,” as the eminent microbiologist Rene Dubos has said, “lasted so long–several hundred thousand years–that it has certainly left an indelible stamp on human behavior…. The genetic determinants of behavior, and especially of social relationships, have thus evolved in small groups during several thousand generations.”

And so it is that I was born in a village in upstate New York and spent most of my first twenty years there, and that has made an imprint on me–on my philosophy, social attitudes, certainly on my politics–that has lasted powerfully for the rest of my life–even though I spent thirty years of it in its antitheses, Manhattan. I don’t know what the population of Cayuga Heights–overlooking Cayuga Lake, as you might expect–was in the 1940s, but I seem to remember it as being something just over a thousand.

The local elementary school was small and the classes no bigger than twenty, if memory serves. I can remember when it was proposed that the school shrink from eight grades to six, with students to be bussed down to a junior high school grades seven to nine, and I can remember facing what I thought was a large crowd in the school basement when I was one of two students allowed to speak up against the change. I lost then, and not for the last time in a worthy cause, but something in my genes flatly resisted the idea of leaving a human-scale school for the vagaries of education down in the city of Ithaca. All right, not a big city–I guess about 20,000 then–but it seemed bug enough to me.

Not only was the community small but it had something it called the Community Corners as its economic hub, and that was no more than a grocery store, dry cleaners, book store, and maybe a small variety store. I worked in the grocery in the summers for three years, and my impression is that the Corners functioned less as an economic hub–it couldn’t have been doing that much business, and larger, fancier stores were available a few miles away in downtown Ithaca–than a social one. People would gather and talk in knots, in the parking lots, on the sidewalk, at the meat counter in the back, and so many people used to come through the checkout line at my cash register on Sundays with only one or two items that I used to wonder whether they had come out of necessity or just to see other people after church.

The fact that my end of Cayuga Heights blended in with some farms as it went northward, not all of them working but still with open fields where birds sang and fireflies danced in droves, also had some effect on me growing up. I used to skate and play hockey on the pond at one place where the old farmer never even seemed to venture outside in the winter, and I would ride my bike down dirt roads that seemed to lead nowhere past farmhouses and barns that varied from spanking neat to decrepit. Somehow I had the sense that I was connected to people who knew the land, knew how to grow things (besides a Victory Garden like my father had), had some solidity and longevity in place (unlike my family, new to the village).

So I want to argue that in some sense it was inevitable that when I began to formulate a politics, it had to be in opposition to the big, the oppressive, the autocratic, the expansive, the all-embracing, in favor of the communitarian, the local, the democratic, the human scale. I guess it was as a first taste of this that I led a demonstration of some 3,000 students at Cornell University in 1958 against an authoritarian university that declared it was acting in loco parentis (when one of the reasons people liked college is that they escaped their parents), decided to forbid “petting and intercourse” by undergraduates, and diminished student self-government. And not long after that I was led to Murray Bookchin and his arguments for anarcho-communalism, which were in some ways (though I didn’t think of it at the time) a kind of working-out on a grander scale the experience I had had subliminally as a kind growing up in Cayuga Heights.

After that, a career writing about decentralism, participatory democracy, human scale, small-is-beautiful, the corruption of centralized American government, the evils of discovery and conquest, the tyranny of the Industrial Revolution, and now most recently secession and self-determination may be no more than something based on “the genetic determinants of behavior” growing up village.

8 comments

N. P. West

The problem with Vermont as I see it is that the native population has been supplanted by urban refugees and their progressive worldview. An example of this would be my great-grandmother, a native-born Republican who took pride in her Vermont roots and was a typical taciturn Yankee. When Vermont passed civil unions in 2000 we were watching television together and she turned to me and asked “what is a civil union?” When I explained she shook her head in disappointment.

The point is that what Vermont represents now is an artificial creation of a progressive elite who left the urban centers of New York and Boston or who came in the 1960s and 1970s to practice their New Leftist and countercultural ideas. As is evidenced by my great-grandmother’s reaction to civil unions there is a disconnect between the communitarian worldview of native Vermonters and the cosmopolitan worldview of those “flatlanders” who came later.

D.W. Sabin

Medaille,

A fine comment, to your everlasting credit, you have left me speechless.

John Médaille

What is not generally recognized is that New York City was actually a collection of villages, thousands of them all jammed together, each with its own identity and, usually, ethnicity. Most New Yorkers knew very little about the “tourist” New York, and when they visited that place, they were tourists themselves, no more knowledgeable then the guy next to them from Iowa. The Statue of Liberty was as exotic to them as to the outlander, and the theater district was a foreign country.

I say this because the discussion of place should not, in my opinion, be about “urban vs. rural,” or city vs. town. Rather, it should be about the proper relationship between town and country, about the proper construction of towns, of whatever size. Bill Kaufman is, I believe, from the Buffalo area (Hey Bill, ever visited Medaille College?) and Kirkpatrick from Vermont, all fine places. But I grew up in New York and Los Angeles, and I know well that one of these was a “place” and the other was not. I lament the decline of New York, which is equivalent to the decline of its “villages,” and I know that every city is not Los Angeles. I think that great cities really can be great. “Small is Beautiful,” to be sure, but as E. F. Schumacher pointed out, it is possible to achieve smallness in the midst of the gargantuan, it is possible to find the human scale even in the metropolis.

At one time, Los Angeles was the future and New York the past, but now LA has no future, and the question is whether NY can build on its past. I believe that we need the village, but we all need the great cities, and we need them to be great.

Esmeralda_Pearl

Community Corners is still there. Nowadays, where the roads intersect, it could truthfully be renamed “Confusion Corners.”.” The Corners has become as congested as the old “octopus!” 😉 🙂

Dylan Hales

You are probably aware of this already Bill, but the Bookchin/Abbey split was part of the broader Deep Ecology v. Social Ecology debate that continues to divide much of the environmentalist “movement” today. Abbey, like his friend David Foreman, was an ideological Deep Ecologist. Bookchin saw that world view as inherently anti-human and a perversion of ideas he had been a major advocate of for years (Social Ecology). The end result of this was Bookchin’s dismissal of much of the anarchist movement as “lifestylists.” In turn the primitivist/green anarchist/deep ecology crowd marched themselves out of the historical anarchist mileau entirely and declared themselves to be “Post-Left” – a transcendent state that has proven to be more interesting in theory than in practice.

There is an interesting book chronicling the Foreman/Bookchin debates that will explain the details, but this is largely a case of philosophical abstractions stamping out similarities. Bookchin’s swipes at Abbey were just one manifestation of this.

D.W. Sabin

Bookchin , if he called ole Ed an “eco-fascist” really should be flogged mit snow shovel because Abbey might have been an eco-curmudgeon or an eco-anarch or an eco-bard or even an eco-godamnyouanyway but he was always too busy trying to spike the gas tanks of the Fascists to join their sordid league.

Imprecision in imprecation is impudently improper. He should chew his cud a tad more before speaking next time.

Bill Kauffman

Hey Kirk, my Upstate landsman, nice piece. I’d love to read you on Murray Bookchin. I’ve found him nigh unreadable, though I am perhaps prejudiced by Edward Abbey’s loathing of Bookchin, whom he called a “fat old cow” who deserved to be “whupped with a snow shovel.” (Bookchin started it by calling Abbey an “eco-fascist.”) Burlington friends have described Bookchin more charitably–as a curmudgeonly character, very much part of the scene. I hope you post something on Murray B sometime.

Patrick

Oddly enough, I support decentralism, human scale, and small is beautiful because of New York City. My experience reading Jane Jacobs convinced me that places work best when they are built at a human scale. And I don’t think this view conflicts with my love of the city – it is possible to build the city at a human scale. We simply haven’t been doing it.

Comments are closed.