Devon, PA. Outside of certain, very particular, Christian circles, one seldom hears much about man’s fallen nature anymore; and yet, as G.K. Chesterton once observed, original sin may be the only religious dogma we can confirm simply by opening the newspapers. In the disgruntled and disaffected remarks that smatter the conversations of private life in liberal society, we encounter routine complaints about this or that attribute of human nature whose presence seems at once distinctively human and intrinsically troublesome-something that makes us uniquely who we are and yet is, perhaps, not worth the bother. Such things appear as realities that must be sloughed off if we are ever to reach that painless utopia our domination of the world seems to promise-a utopia where human beings will not be welcome as they now happen to be.

I would include human sexuality as typical, even foremost, in this sort of complaint, and not only because the heartache of trials in love so dominate our narratives or even because the temporary, bitter swearing off of such entanglements seems such a typical (if vain) effort at cutting the Gordian knot of suffering altogether.

More abstract items have appeared in this catalogue, however, including reason, and scientific reason, and acquisitiveness; and so too have those more concrete entities that seem to exist entirely outside us only to the degree we have become alienated from them. Edmund Burke called man a “religious animal,” and did so to defend religious belief as a part of human nature against an age that insisted “religion” was just an antiquated, calcified institution as foreign to and hobbling of human life as we might find things were we suddenly to fasten tortoise shells onto our backs and bear them as clumsy, inexplicable burdens. All these items share in the peculiar way they at once explain man’s place in nature, in the world as we find it, and yet set him outside of it as well. We sometimes think of sex and love as what constrains us into beasts, and sometimes as the province where we can most fully elevate and transcend the urges of our bodies.

One may be disappointed to hear, however, that the most incontrovertible aspect of human life that clearly meets these criteria-that appears frustratingly problematic, that sets us apart as the pinnacle of creation, and that, nonetheless, weaves us into nature and reminds us of our belonging to it-is none other than speech. A surfeit of language alienates us from the world, no more so than in modernity where the noise of mass culture has become so thick that even its propagators, the admen, call it “clutter” and are continuously engineering new ways to cut through the clutter in order to add to it. But the age-old silence of the stoic reminds us that the place of speech is one that always threatens to swallow and destroy the person and so, under some circumstances, the only means to persevere seems to be to cut oneself free of the chords and cords of speech. The Jewish and Christian admonitions against idle talk-which so quickly becomes the idol, talk-are not identical with such stoicism, but nonetheless express an appropriate suspicion of how quickly the saying of words departs from the way to life-whose means and end is, it turns out, the Word-to a way of vanity and death.

Against this noisy alienation, however, the more typical response is not a stoic’s silence, but a desperate search for some sign that our very human making of signs can be meaningful and good. Hannah Arendt argued very powerfully that the act of speech-when not futile, that is, when actually heard-was the distinctive achievement of the man who lives well, of the man who would indeed become fully human. On her account, labor and work are servile activities, and so only that particular kind of activity she dubs Action qualifies as properly human. Man is a political animal, she tells us, and so when he acts in the public realm he becomes political. She means by “the political realm” something other than the floor of the legislature or the bureaucratic burrows of the West Wing: any place where a man can speak and be heard by his equals. Only in speech does man have the opportunity to assert his particular character, his singularity among a plurality of other men, which makes him himself rather than simply another instantiation of a species. Speech is the ground of our distinction, as it is of our equality. She writes,

If men were not equal, they could neither understand each other and those who came before them nor plan for the future and foresee the needs of those who will come after them. If men were not distinct, each human being distinguished from any other who is, was, or will ever be, they would need neither speech nor action to make themselves understood. Signs and sounds to communicate immediate, identical needs and wants would be enough . . . Speech and action reveal this unique distinctness. Through them, men distinguish themselves instead of being merely distinct; they are the modes in which human beings appear to each other, not indeed as physical objects, but qua men.

Arendt is surely correct in her account of speech. Life without that particular kind of speech that transcends mere “communication” might be an efficient and biologically flourishing life spent amid a multitude of one’s fellows, but it would not afford the occasions of dignity that allow men to speak of their conceptions of what is good and to reveal themselves as something more than contingent and equal instantiations of an animal species. The speech of one man can never entirely be that of another; and when one speaks in the public realm, as Arendt describes it, that act is not reducible to the content or the use-value of those words. Words carry a part of oneself out into the world and, indeed, constitute the process by which we build up ourselves from mere specimens to fully realized persons who can seek not just our “needs and wants” but the good life for men and even the Good itself.

Arendt’s readers have frequently protested her denigration of labor and work in comparison with Action, and they are right to do so; for if we do indeed become uniquely human in the act of speaking ourselves, such speech does not fully express our social or political nature. We know this so well that to speak of our “alienation” from the world is common enough to be trite. The aspirant Aristotelian seeking to recover the dust of that spiritual polis dissolved in the filthy modern tide, and the spotty and angsty teen with a taste for the noir, both sense that ours is a world where men feel solitary even as they feel unremarkable as well. A sack of cells capable of consuming whatever it can afford so long as it obeys the rules, most of us sense we have lost something more than occasions to hold forth among our fellow citizens-though mass democracy has certainly guaranteed we lost that. Indeed, what is so often denied the contemporary person is the sense of participating in the meaningful work that makes possible the public realm Arendt celebrates.

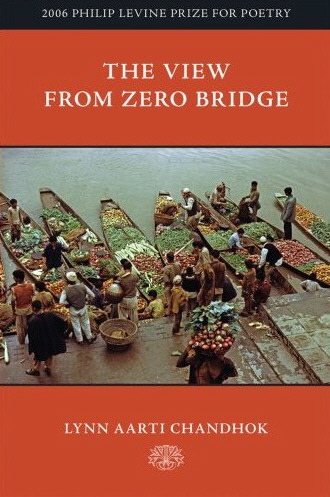

Poetry and other rhythmic art forms have made themselves into the place where we find just this desire and its fulfillment expressed, in large part because the “fine arts” are, according to Arendt, the only instances of true work left in modernity; the fine arts are made, everything else is produced and consumed ad nauseum. We see this with particular clarity in a stunning poem of Lynn Aarti Chandhok’s, “Inside the Carpet Factory”:

At each loom, sitting Bhuddha-like, there’s one

old man who reads the pattern off a scrap

of paper bag he’s tucked into the strings.

The penciled letters look like notes. He sings

instructions like a prayer-the rāg‘s a map

of roads that bleed like watercolor, run

the wrong direction, double back, then bloom

into a tree in bloom. The workers hear

the melody as knots, not notes, the line

as dots to be connected. Rows entwine

according to a master plan that’s clear

only to the old man-until the loom

recedes, leaving a veil of silk threads bound

by what’s unspoken, taking shape from sound.

Much of this scene is servile, Arendt might tell us, and certainly what it shows us is not human speech making the human person shine forth in some singularity, but a revelation of some kind there is. The “Bhudda-like” old man reciting the pattern off a scrap of paper bag: he sends words into the air, and those words are song, his song is command, and that command finds immediate, agile and docile answer in the work of the weavers. Surely this is an instance of signs “and sounds to communicate immediate, identical needs and wants,” but this does not seem an adequate account of the marvel to which Chandhok bears witness.

In such a moment, we see man at his most dangerous, given over to the mind of another and becoming not just a worker but work itself; and we see man at his most beautiful, weaving a gratuitous order into the already ordered world. Insofar as he does that, man’s speech affirms the purposive character of his existence as a part of nature; he does not merely live upon the earth, but enters into its rhythms. Indeed, when we speak of the harmony and the songs of nature, we affirm by figure of speech that our speech and our music at once derive from the natural order around them and also provide the paradigm by which we can see much less understand that order. Note that this is no mere work-song; there is not that sort of gratuity here that suggests the indignity of labor might be made more bearable when accompanied by the pleasure of words and melody. The weaving rhymes of this sonnet enact the auditory notes of the old man as they enter into the pattern of knots that will constitute the pattern of the rug. In the poem we see, and the poem itself reenacts, music as work, words as work.

A rare and cloistered scene in itself, “Inside the Carpet Factory” may remind us that the foundations for a human life that human work builds are no less important than the sense of fulfillment discoverable in the kind of speech Arendt celebrates. It testifies above all to the variability of speech, which can sometimes deafen and frequently seduce and even control us. For Arendt, speech only truly becomes itself when it acts purely as a revelation of the person in his singularity, as a distinct being taking his unique place in a plurality of equals. But Chandhok’s poem affirms that speech is one significant means by which man gains a sense of himself as belonging to others as much as he stands apart from them, and that he fulfills himself as part of a larger work, a way of life. The song-that-is-work, here, reveals him as belonging to an order of reality on which he depends and which is the setting in which he discovers the harmonic beauty of things when they are not particularly seeking to stand out but only to conform to a sound and useful pattern.

7 comments

James Matthew Wilson

Fair enough. It is an ugly word.

I concur in avoiding the techno-neologisms. How ugly.

I further agree with abstaining from Facebook until that strange artifact has properly conformed with a modern American sense of equity. Until all asses are treated with the respect of faces, our society will have failed to live up to its promise — as you say — to pretend that all men have been created equal. How curious that so many people believe that all men are created equal, and yet, present someone with the premise, “all asses are created equal” and he will vehemently deny it, unless, of course, he knows already that he is the biggest ass.

I’m talking about domesticated farm animals, incidentally.

D.W. Sabin

Wilson, Though chary of some forms of media vocab….snark hits paydirt for me because it is one of those words that actually sounds pejorative, a repulsive sounding word for repulsive behavior. It sounds like the call of a malign bird, chattering about the low hanging branches and It verily defines the average movie reviewer who thinks it their role in life to drip sarcasm in a kind of dimbulb haiku of conventionality. I do promise, however, to neither “Twitter”, nor join Facebook, until they have a Division called “Assbook”.

James Matthew Wilson

D.W., your last comment inspires a question. Has “snark” been promoted from the land of grunts to the condign vocabulary of the Front Porch elect? I vote, no!

D.W. Sabin

Esmerelda,

You undersell yourself. The fact that you show up and enter the fray is a productive eloquence all its own.

You also possess that fundamental bookend of eloquence…an ability to assert but also to listen and show respect for those you do not agree with……..something wholly at variance with the current atmosphere of hit and run snark.

Esmeralda_Pearl

Mr Wilson, thank you. 🙂 “clutter” sums up our modern society.

D.W., I have never been eloquent, in writing or in speech. Please know that I appreciate reading your words and those of the other authors at this site. I enjoy and appreciate “an arcane or unusual word”. Thankfully, the internet has allowed forums such as Front Porch Republic, The American Conservative, Taki Mag and Chronicles to exist with an almost limitless readership. 🙂

D.W. Sabin

….”he does not merely live upon the earth but enters into its rhythms”. Well said. Despite the high percentage of schooled people in the U.S. , there is a kind of creeping functional illiteracy afoot. Truncated sentences interspersed with grunts are a means to an end and speaking is merely sufficient…..rather than elevated to a craft that evokes both discipline and artful expression. Anyone attempting to utilize an arcane or unusual word for it’s very precise descriptive power is deemed a crank or braggart. Discursive fads abound in a language of slogans. One of the great pleasures of the English language is it’s layering and polyglot nature and here in this country, where the polyglot was most unleashed, it is becoming deracinated and well on the road to mere gruntery.

Comments are closed.