Devon, PA. Last month, I alerted FPR readers to the appearance of the first part of my essay, “Art and Beauty against the Politicized Aesthetic,” in First Principles. The primary subject of that essay was the consequence of contemporary conservatism’s institutional-political obsession, namely, conservatism’s loss of any purchase or influence on the shape of the broader culture beyond the Beltway. I suggested, further, that the aesthetic sensibility typical to conservatives, while admirable in itself, was also stunted; a taste for the “noble” seemed to operate to the exclusion of the other forms or expressions of beauty necessary for a vibrant appreciation of the fine arts — and, further, for a living cultural tradition worthy of defending and cultivating. The Greek word Kalon, I observed, translates as “the noble” in the context of rhetoric, but properly refers to “Beauty.” And so, in proposing a deepening of the contemporary conservative understanding of Kalon, I articulated the mission to which I call not only conservatives but all persons; for our age, as a general rule, pretends beauty is but an ideology and divides the fine arts into the detritus of the culture industry, fit for human consumption but not for human thought and flourishing, and high art, which generally subsists in a state of self-loathing, flailing at, alternately, the naive ideology of beauty typical to arts prior to the present or the culture of absorption and consumption manifest in the “entertainment” industry, advertising, and the other excretions of “corporate humanism” that dominate and decimate our cultural landscape.

Unless we learn again to appreciate that questions of beauty are, by their nature, also questions of good and evil, truth and falsehood; unless we learn again that in themselves questions of art and beauty are questions in which forms made or seen echo and ramify in the larger waters of our form of life; unless we perceive that Beauty Itself is the voice of our calling; we are all doomed to presume our already advanced degradation is deserved and might as well continue apace. The careful study of a little poem, the casual but sincere elation at a public fountain should serve as the basis for resisting our reduction to creatures of merely zoelogical needs, and refusing our worthiness to be treated as subjects for morally indifferent manipulation by machiavellian technocrats responsible only to the quantifiable assessments of sociologists and bureaucrats. Art, so long as it feels the call of beauty, resists such degradation not in the manner of one more practical strategy or technology in a world obsessed with reducing everything to method and control. Rather, the arts of the beautiful are so many small lights flashing along the dark coast, reminding us that there is more to the rock of this world than what we reduce to use-value, and that we ourselves are ordered to something beyond the maximization of that use-value. They do this, perhaps ironically, in a practical way — for art is, by definition, practice.

I was not entirely happy with the account set forth in Part I only because it ignored a fact that makes contemporary conservatism look grotesque in comparison with the figures and traditions from which it weakly derives. To wit, conservatism historically has manifested itself as a literary, cultural, and intellectual phenomenon rather than as an active political one. In the last two centuries, the most prominent Anglo-American literary figures have been in some sense deeply conservative; they stand as part of a coherent pedigree that itself stands in opposition to the cult of progress — urbanization, industrialization, statism, cultural leveling, crude rationalism — that correspondingly defines the worship of modern liberals. In order to understand the strange paucity of cultural contributions and cultural concern of contemporary conservative political figures, in other words, we must first see that such persons appear as dull anomalies set against the stary night of those who constitute conservatism’s great tradition.

And so, in Part II of this essay, I seek to add some historical depth to the portrait painted in Part I. Beginning with the Revolution controversy and the dispute between Edmund Burke and Mary Wollstonecraft, which I take to be the foundational moment of conservatism, I suggest that the conservative movement, if it is a movement at all, has been a literary one. As such, the attacks on Burke, Wordsworth, and Coleridge–those foundational conservative thinkers–by the liberal critic William Hazlitt and the utilitarian reformer William Godwin,

collectively express a fear within the Anglophone liberal Protestant tradition that Diderot had also contemplated from within French Enlightenment liberalism: the world to which liberals were committed politically would be one true to Wollstonecraft’s words, building a Chinese wall between sensibility and reason, truth and beauty. That is, the world they fought to bring into being would prove one no longer worth imagining, no longer capable of giving aesthetic pleasure or of eliciting our love. Liberalism was a hortus siccus, incapable of life of its own; its fiercest advocates reflexively drank and sought to contain the fructifying waters of conservation and reaction that Burke, Wordsworth, and others came to represent. In this respect, conservatism in the post-Revolutionary world might better be described not as a literary movement but as the continued source of literary achievement in a world committed to rationalizing such things to extinction.

The essay leaves certain points unsettled. For instance, given the partial perversion of contemporary conservatism into a neo-liberalism owing as much to the French Philosophesas to Adam Smith and Thomas Paine, might we not have expected a shriveling of the literary and artistic achievements of conservatism? Furthermore, insofar as we confuse classical liberalism or neo-liberalism with conservatism — that is, insofar as we take conservatism for a constellation, first, of the hawkish advocacy of an empire of democracy and, second, of a superstitious worship of the free market as an autonomous good — might we not say that the true literary antecendents of the neo-conservatives of our day are Rousseau, Diderot, and Voltaire? That is, those who lend to the term “conservative” a certain pliability may understandably contend that there are very few literary figures who do not in some sense belong to its “tradition,” and that, therefore, the term “liberal” might be deployed simply as an expression of ascedia and sterility. If we must accept such wide definitions, then the words “conservative” and “liberal” seem of little value in themselves, save perhaps to cement still further the association of modern liberal society with the listless, violent, and banal.

The aim of Part II is to suggest that there is a particular conservative tradition beginning with Burke and the two great Romantic sages, and continuing on through Cardinal Newman, G.K. Chesterton, and T.S. Eliot, on — one hopes — into our own day: a particular tradition in the sense that it has a specific content and a limited number of representative figures. If a soi-disant conservative does not recognize his face in the mirror I hold up, my suggestion would be that he has misconstrued something about our history and about himself. If a soi-disant liberal wishes to appropriate some of the figures I mention in the essay — well, I account for that, since it is largely by being appropriated and preserved like seeds within the belly of the liberal beast that the great conservative minds were even available to be discovered by hapless fellows such as myself. Were the liberal order not able to absorb conservatism under the trace of aesthetics and nostalgia, of imagination and arcadia, its tradition would be far more buried than it already is. But even such claims are of limited interest, and, in writing on it, I hope merely to preface the more significant concerns to appear soon in Part III, where I shall try to account for the continued presence of beauty in modern art by means of two of that art’s greatest theorists, Theodor W. Adorno and Jacques Maritain.

12 comments

Janotec

Thank you for that last note on Eliot. It was a lot more pleasant (and informed) than what I would have fumed.

Great man indeed. Saint? I don’t think the old banker would agree, not as one who mourned the hyacinth girl.

James Matthew Wilson

This isn’t the place to get into a dispute about the meaning of Eliot’s “Dry Salvages,” Hudson, but it seems that if you ignore the conclusion to his poem then you are necessarily going to get a reading a) at variance with one that takes account of the whole poem and that is b) wrong. The Quartets moves dialectically, following the practice of John of the Cross, where verse and prosaic sections trade off, alternating lyric intensity and repose. The conclusions to each Quartet reconciles these stylistic alternations and, consequently, presents the most weighty intellectual conclusions in what may appear the formally briefest manner. Ignoring them altogether is sure to drive you to the wrong interpretation.

Far from repeating After Strange Gods, Eliot repeated its central theses in several different forms; the positive arguments about community he repeats in the two essays collected in “Christianity and Culture.” His discussion of blasphemy (with Lawrence, et al.) is repeated also, perhaps best in his introductory chapter to a book called “Revelation” (Faber and Faber, 1937). I don’t think he had anything to repudiate or retract with the *possible* exception of that phrase “free thinking Jews,” the intellectual emphasis being on “free thinking,” which means, of course, atheist, and the “Jews” being a rather significant flourish that answered well to English prejudice. Again, the consensus argument among Eliot Society scholars is that this phrase needs to be read as a critique of Unitarians and liberal Protestants.

As the author of a forthcoming book and several essays on Eliot’s writings, I doubt I fit the bill of someone who has not and does not subject Eliot to critical scrutiny. I just think he was a better man than most men; I trust the opinion of established good men like Russell Kirk, Tomlin, and Jacques Maritain more than I do the anecdotes of someone whose character I can hardly scrutinize.

Hudson

James, thanks for the riposte. It’s always nice to be noticed on a board like this.

I reread all five sections of “The Dry Salvages” with your comments in mind. I found the usual stew of ideas, sense perceptions et al, characteristic of Eliot’s longer poems. However bright Eliot might have been, he was not a disciplined writer. I found references to Krishna, continuing the author’s long interest in Eastern religion, and an invocation to the Virgin Mary as Lady of the Harbor, not substantially different from an argonaut’s prayer to Posidon. I don’t think the Incarnation at the end has the force you ascribe to it; it arrives softly like an afterthought. It is not the “animating spark,” as I call it, that gives the poem its weight and beauty, that makes it worth reading.

Eliot was not a pagan, per se, but one could make a good argument that in his poems he was something of a polytheist. You have to take the poet for what he wrote, not what you might wish for him. Also, certainly in part one of “Salvages,” I feel a touch of Whitman. The brown river might well have been the Mississippi, running alongside St. Louis, where Eliot grew up. It’s a very American poem with beautiful passages, an arc and flow to it.

I have always felt that Eliot’s anti-Semitism was of a literary variety. He blew smoke in the face of the Jew, nothing more. He is not claimed as a source of Nazism like Wagner, for example. He was basically a decent Christian gentleman. Still, he did stick out his WASP chest rather boldly during the period that Auden called “a low, dishonest decade.” Refusing to republish After Strange Gods does not exonerate him from writing it. Did he ever publically repudiate it? If he had been smarter and put his ear to the ground like William Shirer and others in Europe, he might have seen what was coming and kept quiet about his petty prejudices.

Never suppose that an author is so intelligent that he gets a free pass from critical scrutiny, that you feel compelled to worship him. Eliot was a complex man and deserves sympathy on some accounts. He did not speak with one mind. In his own way, he was a stoic fighting through nervous crises for years to arrive at personal happiness, which I would ascribe more to his second wife than to religious doctrine. I listen to plenty of desperate women on the subway who yell about how Jesus has changed their lives. You owe it to your students to give them the whole man, warts and all, and not a rose window view of him.

James Matthew Wilson

People seldom notice the photos I include in my posts, Hudson, which is a shame because, among other things, awhile back I included photos I took of original letters exchanged between Jacques Maritain and Allen Tate. Interesting things, in other words, I mean to point out but sometimes forget.

It’s good, also, to see you come by the porch regularly; welcome.

Now, as for “Dry Salvages,” the poem is a critique of paganism. You are right that its opening lines are pagan. That is their point. As with all the Quartets, the opening movement is the errant position from which the rest of the poem moves away and to which it provides correction. In that poem in particular, the temptation the first movement presents is the pagan understanding of gods as intra-historical natural forces, as mere giants within the scale of a nearly infinite, temporal history. By the end of the poem, we learn that gods are not God and that infinite time is nothing like eternity; thus the Incarnation of Christ serves as the our pathway of “escape,” as the means by which we ascend beyond the pagan gods of immanence and enter the eternal life where experience and meaning are one. You are the first person to get a taste of what my Reader’s Guide to Eliot’s Poems will sound like.

Eliot never espoused anything Nazi-like, in fact. He was one of the earliest and most penetrating critics of the modern nation state and political religions. The comments in “After Strange Gods” are embarrassing (hence he never reprinted them), but they are also almost certainly an instance where Eliot identifies what he calls “free thinking Jews” with, well, Unitarians. He was born and raised Unitarian. We have here an instance of self-critique.

As I’ll argue at Notre Dame next month, Eliot’s chief target of criticism was stoicism. The stoicism of Shakespeare, the stoicism of Unitarianism, the stoicism of anyone who denied the integral relation between the life of community and the law of God.

I’ve gone on enough, but let me finish by saying here what I say to students of mine who would write on Eliot. He’s the only modern author I have read who is always already smarter than us. Any criticism of his thought or character I have encountered I have found always to have been anticipated and thoroughly routed in his own writings; see especially his dissertation, where, as a twenty-something kid in Oxford he invented and critiqued phenomenology and grammatology a) before he could have heard of phenomenology and b) decades before Derrida started casting words on the wind.

Read E.W.F. Tomlin’s affecting memoir of Eliot, and see if you do not conclude Eliot’s was at the least a great man and very probably a saint!

There’s my gauntlet, God bless.

Hudson

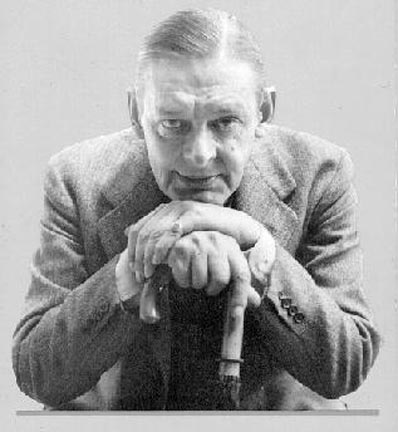

I see it falls upon me to notice Old Possum grinning at the top of the page even though he is barely mentioned in the essay. Eliot’s life was certainly not beautiful like a stained glass window. Compared to an aesthete like Rilke, Eliot’s verse is not beautiful either. Whereas Eliot speaks with authority, Rilke sings.

You could not imagine a more conservative looking person in life than Eliot in his banker’s suit. Ezra Pound wore flaming yellow trousers, by contrast. As a poet though, Eliot was the modernist tiger, while Pound stayed with his 19th Century diction. In essays, Eliot hammered out his ideas of the poet and society, and mounted a defense of his religion and class, going overboard with quasi-Nazi ideas in the 1930s. In his poems, the animating spark might well be pagan, as in these lines from The Dry Salvages:

‘I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god –

…

His rhythm was present in the nursery bedroom,

In the rank ailanthus of the April dooryard,

In the smell of grapes on the autumn table,

And the evening circle in the winter gaslight.’

I met an old Irishman at a theater workshop in NYC in the 1980s, Michael Sayers, who was then in his 70s. He had worked with Eliot on the Criterion literary magazine in London. I asked Michael if Tom Eliot was the morose man in reality that he was depicted as in print. Michael said “yes” without hesitation. Eliot suffered greatly and eventually attained happiness and grace after his second marriage. His virtues were determination, forbearance (with himself), and humor. It is not entirely unfitting that what he is primarily remembered for today is his contribution to the musical Cats.

Bob Cheeks

James, excellent essay!

Ralph Wood!!! Whoa, yes, I agree with Dr. Wilson, I’d like to read his essay on the above mentioned point!

James Matthew Wilson

The Front Porch would be grateful if Dr. Wood would provide a complete essay on this point; we would be honored to post it. But, since I just happened to be typing the following passage from Burke into another essay, I’ll paste it in here:

“One of the first symptoms they discover of a selfish and mischievous ambition, is a profligate disregard of a dignity which they partake with others. To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country and to mankind.”

Chesterton says early in his “Autobiography” that the two truths he advocated for during his whole life was the rediscovery and cherishing of the family and the foundation of gratitude for the mere fact of existence. Burke seems in every way a great antecedent on these two points.

The similarities may end there.

Ralph Wood

It is difficult to link Burke and Chesterton as belonging to the same tradition when the former made the French Revolution one his chief targets and Chesterton made it one of his chief vindications.

D.W. Sabin

Somewhere in my grazings of the last several days, I overheard a talking head quote Chesterton as saying

Liberals seeking to change things manufacture mistakes while it is the Conservative’s job to make the mistake of not reforming the original mistake…….or words to that effect.

As to abstract stained glass..the most remarkable and almost hallucinogenic stained glass I ever had the stunning pleasure of seeing is the upper chapel of Saint Chappelle, built in the 13th century on the Isle de Cite. The ecstatic fluidity of the Rose Window is remarkable. Stare too long and it begins to move and the space begins to resonate and you begin to question your sanity and then the guide breaks the spell. Then again, upon closer inspection, the glass is not abstract, it simply looks that way in total. It is one of those places you wish you could spend a day from sun-up to sun down in…with a ladder and only a brief break to go out and get one of those tres fromage pannini at a sidewalk stand that are also swoon material.

Then there is Corbu’s Ronchamp and a massive, brutalist stained glass wall that whispers mystery and evokes starlight or a distant city flickering at night. Was he thinking of Augustine? I doubt it would be a child’s favorite place but the hushed mystery and robust forms engendered deep spiritual feelings in me.

There is also a form of narrative in religious expression as presented by that new museum of intelligent design where lifelike statues of children cavorting with large reptiles creates an entirely legible story of hilarious quack-brained excess. Narrative, to be worth a plug nickel must have something transcendent within it, a healthy dose of mystery and sometimes, to me, abstraction pulls this off better than the literal…and prosaic.

But as to Your Volume II;

A stirling essay !…the pejorative of mere eloquence and the preening superiority of the pragmatists and their armoring of Reason. To what perversion we have come down to with anti-intellectualism beating the dead mule of conservatism. This is one of your more illuminating pieces …thanks for it.

Not to mention ,

“…discovered the dry powder of conservatism tucked away in the base of the heaving windmill of modern liberal society”. Such romantic descriptive stage-setting….How downright unreasonable of you!

Romantic puffery worthy only of a derogatory tongue lashing by Ms. Wollstonecraft in her pseudo-peasant get-up. Limo liberals were once horse drawn. At least they were forced to reckon with horse pucky whilst in transit.

Now finish Part III and make it snappy …skippy. If you’d stop staring out that window at the fall foliage, you might have the discipline, clarity of mind and benevolent purpose to achieve the victorious logic of completion.

James Matthew Wilson

Let me begin, Casey, by seconding your story. Six miles in the opposite direction is Our Lady of the Assumption, where my three year-old began explaining the Stations to a little old lady and her ward; I don’t remember what else she said, but at one point she pointed to the Roman soldiers about the Cross, and said, “They’ll be sorry.”

The Anglo-American conservative tradition begins with Burke, and runs through Wordsworth and Coleridge into the Oxford movement; that’s a simple but accurate historical geneaology. Naturally, we’re dealing with broad categories here — if we don’t accept that, then we are merely confusing things to think of a theological and ecclesiological movement as standing in any relation to the word “conservative.” Burke’s theory of society as organic, with his theory of the constitution as a community of prudential readers addressing, reinterprting, and developing custom in the light of present experience translates quite precisely into the theory of Tradition that the Oxford movement worked out. The constitution abides organically as a “possession” of the community it binds, for Burke; doctrine abides in the Church tradition, with the Church as the interpreting people of God, for Newman. Whether Newman’s ecclesiology varied from this after his conversion to Catholicism is another question, and one that I’m not equipped to answer (though I would like to).

In any case, any art that tries to short-circuit, conceal, or deny its dependence on narrative is art that may be of experimental value, in a sense, but is ultimately a limited or even a bad art — for the simple and true reasons you suggest. If Memory is mother of the muses, then surely we depend on the stories of memory for the making and perception of art.

Post Vatican II Liberal Catholic obsessions with “getting modern” in terms of architecture strike me as expressing a kind of self-love and self-possession neatly analogous to the homosexuality (the physical self-love of like-and-like) those same liberals call on us to “lighten up” about and which have, of course, bankrupted diocese after diocese.

Good art engenders, it reaches out to another, it communicates or speaks to us. Even difficult art does this, if it is any good, but why one would adorn churches with difficult art is beyond me. St. Ann’s Church in Somerville, MA has many stained glass windows, all but one of which depicts scenes of catechesis: parents, priests, and saints passing on the Faith to children. The prevalence of that trope speaks volumes about its importance to the people who built that church. What do abstract cubes of light tell us about the contemporary Church’s commitment to catechizing children as opposed to flattering the enlightened sensibility of our swinging age?

Casey Khan

Can we put Cardinal Newman into the same camp as Edmund Burke? I guess if we look at conservatism in a very broad context, probably. Didn’t Newman, however, find substantial fault in Burke since his conservatism was one of conserving a world which originated with Henry VIII’s destruction of the English Church, and its subsequent looting?

Nevertheless, you’re right to emphasize the importance of beauty and its truth. I’m learning this lesson slowly through the eyes of my sons. For example when we initially attended the Rosemont Villanova chapel, the stained glass and art was radically abstract, to which the children could not identify. But when we started going to Our Lady of Lourdes 6 miles up the 30, the beauty of the Church there truly acted as a catechism, one that the little child could understand. My three year old often comments on the stained glass mural of the Holy Family, with St. Joseph and Christ wielding hammers and chisels. He also laments those “bad Roman soldiers!” found in the stations of the cross.

It is through these experiences that I have found deeper meaning in Matthew 19:14: “Let the children come to me, and do not prevent them; for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.” The abstract modern Churches seem to be preventing the little ones from coming to Christ, which I think should play into the consideration of beauty which opens the door to the kingdom of heaven.

Comments are closed.