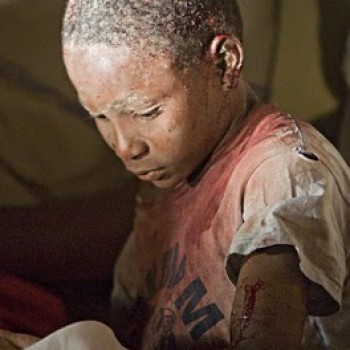

Kearneysville, WV. The recent earthquake in Haiti and the subsequent human suffering touched us all in various ways. Who can forget the images of thousands of displaced persons desperately attempting to cobble together shelter from scraps and pieces of plastic? Who can forget the plight of the children, many newly orphaned, in need of a home? The miraculous rescue of a girl two weeks after the event provided a small bright glimmer in a story whose tragic scope was difficult to fathom.

The scale of the devastation called for a response suited to the magnitude of the need. The U.S. military seemed the obvious choice to help restore a semblance of order and to organize the distribution of much-needed supplies. Yet, with the obvious good that was made possible by a large, well-funded, military operation, what is implied in all of this for the ideals of localism and human scale that lie at the heart of the FPR project?

When disasters like the Haiti earthquake strike, individuals hundreds of miles from the site are quite powerless to do much. So too are neighborhood organizations, local municipalities, or churches. At the very least the perception is prevalent that the modest efforts by small groups need to be orchestrated by a central authority capable of managing the vast enterprise.

In short, large scale disasters seem tailor made for a strong state apparatus that can respond quickly and efficiently to the immediate aftermath as well as rebuild the damaged and destroyed infrastructure. Collective action seems to be called for and the state is the default agent capable of doing the job.

But at the same time, we should not forget the images of Wal-Mart truck delivering fresh water and other emergency items to those displaced by Hurricane Katrina. The response of the federal government seemed sluggish compared to the efficiency of Sam’s people; although, the effectiveness of Wal-Mart was predicated on a level of stability and security that simply does not exist in many disaster areas around the world

So it appears that disaster aid is best delivered by some arm of the federal government or a massive corporation. Is there any place for human scale in a situation where the scale of devastation defies comprehension?

This question of scale is interesting, for our awareness of suffering has long since exceeded our capacity to address it individually or locally. A quick glance at any newspaper, news web-site or television news broadcast inundates the viewer with stories of human suffering around the world. We know about earth quakes in China (Richter Scale and all); we know about the drought in the Sudan, we know about the flooding in Mexico. We are alerted when a child anywhere in the United States is abducted, and we can follow the police search for a missing co-ed that ends with a grisly discovery in a cow pasture. The swine flu comes not only to our neighborhood but to the world at large and we feel the burden. Indeed our modern electronic and print media, constantly pulsating with the news does, in a way, provide us with a means to empathize with strangers around the globe. It makes it possible for us to imagine, if only fleetingly, the brotherhood of man. But the burden of that brotherhood is great, for as we grasp the suffering, we feel its crushing weight.

There are, at this point, several obvious options. One is to shut down. Empathy without opportunity to render aid would, it seems, lead eventually to frustration and the inability to express empathy any longer. We can become calloused to stories of suffering so that we can observe images of heinous brutality on the television news and not lose our appetites or even feel the need to avert our eyes as we consume both our dinner and the news with gusto. The second course of action is to retain the empathy while hoping fervently that the government will do something. Scale and distance leave us feeling individually helpless but quite willing for the government to extend its long and powerful arm around the world. In such an instance, our empathy serves to empower the government as it seeks out missions of benevolence to satisfy citizens who demand it. Of course, the government will be all-too willing to accept this added empowerment, for power is the constant attraction of government.

There is, of course, a third course. Individuals can seek to support, financially and with their time, non-governmental organizations that provide relief services to disaster areas. The Red Cross, World Vision, Samaritan’s Purse, and numerous other organizations provide an outlet for individuals who want to render aid (usually by writing a check). But these organizations require the security and infrastructure that only governments can provide, so there still appears to be the need for energetic government involvement.

Natural disasters are, though, not the only threats that confront us and our world. Weapons of mass destruction present a looming danger. Security officials tell us that an attack in the United States by Al-Qaeda is likely in the coming months. Global warming is not something that any individual or community can do much to address. These issues recognize no borders and seem to beg for a response that is massive, coordinated, and centralized. So the question is this: given the threats we face, and given the expanded awareness of suffering that we possess, how can the centralization of power be tempered and the principles of localism and federalism be advanced?

8 comments

D.W. Sabin

Cecelia gets to the nub of it. Localism does not mean anti-federalism. In fact, the original federalism was far more scaled and oriented to Strong States Rights.

There will be times when the locals need larger help. Unfortunately, at this juncture, the States are little more than functionaries and factotums for Federal Will.

Subsidiarity: from the Citizen to the Neighborhood to the Town to the County to the State to…. , and only when required and appropriate, the FEDS. If these units were more independent to begin with, large scale mobilizations and actions by the FEDS would in fact be strengthened.

Cecelia

my geologist friends tell me that Chevron’s commercial is known to them as the “don’t blame us when oeak oil hits – we warned you” strategy.

I see Prof Deneen’s point re: complex organizations tend to cause complex problems but I am somehwat doubtful that centralized govt causes earthquakes.

It is likely to be true that there are some diasters and happenstances that require resources that can’t be met on a local level. Cetrtainly we already have voluntary organizations such as the Red XCross which go beyond the local. Certainly living locally does not mean abolishing all central or regional functions – if the zombie horde invades our shores it seems unlikely local towns are going to stop them. Of course it also seems unlikely a zombie horde would invade.

I do not think a commitment to living locally precludes a central government whose functions are properly constrained to those things a central government could do best. Maintaining those constraints would be the fly in the ointment.

Jon

PB asks (I presume rhetorically, with answers in mind):

“What entities have the means to undertake such operations, and how do they obtain them?”

Clearly governments are one, and perhaps the best, answer. How they obtain the means is captured in “render unto Caesar”. The real question is: how do they obtain the right to those means, and under what constraints does that right exist? For me, the idea, the institution, of government is a divinely conceived one, and therefore as an ideal serves good purposes. Our human task is of course to try our best to keep it working “good” and not become corrupted as all human endeavors seem ultimately to do.

“Is the generation of “wealth” that enables such entities sustainable?”

In absolute measures of our current capabilities, of course not; but relatively, yes. Pax Romana provided a (relative to the times) stable society for many people to live, love, and die in, for several centuries.

Bruce Smith

It’s not just “the balance is the key” that’s important it’s recognizing which forces, either central or local, lead to dysfunctional outcomes because in operation they offer us little accountability. Accountability, itself, is best if it can be achieved locally and as organically as possible but norms, or rules, often require central and local legislation and enforcement as the “long stop” in atomized and complex societies.

pb

“If we lived in a milieu that was all localism and community, we’d probably be asking for some centralism!”

What entities have the means to undertake such operations, and how do they obtain them? Is the generation of “wealth” that enables such entities sustainable?

D.W. Sabin

When the Teton Dam …an Army Corps of engineers project…..broke in 1976, the small towns of Rexburg and Sugar City Idaho were devastated. It was the Mormon Church, with its extensive Church Welfare facilities and quick mobilization that had relief showing up within hours. There was a constant stream of volunteers between the Wasatch Front of Utah and southern Idaho. People in pick-ups and sedans, helping their neighbor because it was clear to them that they must.

During the Depression, the Mormon church authorities instructed their people to come to the Relief society and they would be taken care of and to avoid requesting Federal Help. My father , whose catholic old man was a Locomotive engineer and so never out of work but for 2 weeks always said the absence of long bread lines in Mormon Country was a notable feature.

Most recently, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, convoys funded and organized by the Mormon church were some of the first organized responders. One creole family airlifted out were somewhat appalled by the fact that they were on a jet headed to touchdown in Salt Lake City, home of the Saints and the Jazz … just not quite the Superbowl Saints. I have not been back to see if there is a good Creole Restaurant on State Street now but hopefully there is.

Suffice to say that the FEDS, as helpful as they are and as critical to the success of relief efforts in Haiti as they most definitely are…they are not the only effective show in town….not now, not a few years ago and definitely not in 1976. In fact, for major emergencies, we would be better served by more mobile and flexible local sources. FEMA’s Ice Convoy to New Orleans, from Iowa, by way of New Hampshire should sum this idea up.

Wallace Stegner, after the Teton Dam bust , remarked that “if I’m ever in a disaster, I hope its within a days drive of Utah”. Given those ramparts of the Wasatch, roaring up in Fault Block drama out of the Great Basin, I am pleased for them that when and if a big one shakes loose, the Mormon church will be ready and able to respond at zero hour.

Now that I have this squared away, I can go back to insulting R.A. Fox’s and half my peoples again for an extended period. …while pondering perhaps a little essay on Brigham Young, uber American Localist. First though, we shall have to build up an inventory of insults.

Jon

I value the ideas of localism and community, and see the value of FPR, not simply because they contain truth but also because our current society is grossly misbalanced against them. If we lived in a milieu that was all localism and community, we’d probably be asking for some centralism! The balance is the key. As Haiti shows, a large capability to act forcefully, a la the US military, can be extremely valuable for good. All the NGO’s depended on that capability to provide a foundation for them to work on, and none of them could provide that foundation. A friend of mine remarked in email that it sure seems like the rest of the first world is getting a free ride on the backs of the American taxpayers when it comes to fielding a globally effective disaster relief capability. Our military is the only game in town (and three cheers to them!).

Patrick J. Deneen

Chevron is currently running a radio commercial in which a pious voice intones (over a gentle piano riff) “where will the energy come from? We will need energy to solve the world’s problems, including the energy to solve global warming….” Get it?

An earthquake is an earthquake, and will wreak destruction in times and places across the globe in ways we cannot prevent or predict (though Rousseau noted that the settlement patterns of Lisbon had much to do with the extent of the destruction in the famous Lisbon earthquake of 1755, and there can be no doubt that Haiti’s miseries have been profoundly exacerbated by social and political policies). Governments and communities variously situated and sized can and will be appropriate to a response. But, we should not let this example obscure the nature of so many contemporary “crises”: today it seems our problem lies more in those various disasters that are the result of the diminishing returns of our various concentrations of power. It is not simply that crises require power; ever more concentrated forms of power generate more intense crises. The title of this post is double-edged – the extent and expanse of modern power increasingly generates more crises, requiring thereby more concentration of power to redress the effects. A good case in point is our recent economic crisis, born of an unholy alliance of public and private power encouraging the creation of entities “too big to fail,” and thereby requiring a further concentration of centralized power that will not be temporary or narrowly focused.

Our tendency is to treat these disasters as things or events that just happen, justifying immediate and permanent concentration and expansion of power. Our contextless, historyless media only exacerbate this tendency (CNN’s sanctimonious disaster coverage seeks to stifle thought by manipulating emotion through imagery). We neglect to do a genealogy of the source of many contemporary disasters – and see how often their severity was generated by those very concentrations of power. A case in point: while terrorism cannot be justified in any form, we neglect at our peril the fact that our efforts to secure cheap energy has forced us to be deeply embroiled in a part of the world where we are not welcome, and where our activities have often been pernicious. Terrorism may simply be yet another “externalized cost” of cheap energy (Once we add in the costs of global warming, an imperial military – whose budget is bracketed from any “freeze” – and “Homeland Security,” “cheap energy” looks like a somewhat less attractive bargain, to be sure). We need a fuller and better accounting, and a better tally of the deeper sources of many crises, before willingly acceding to further concentrations of power. After all, the tendency is, and will remain, not to let any good crisis go to waste.

Comments are closed.