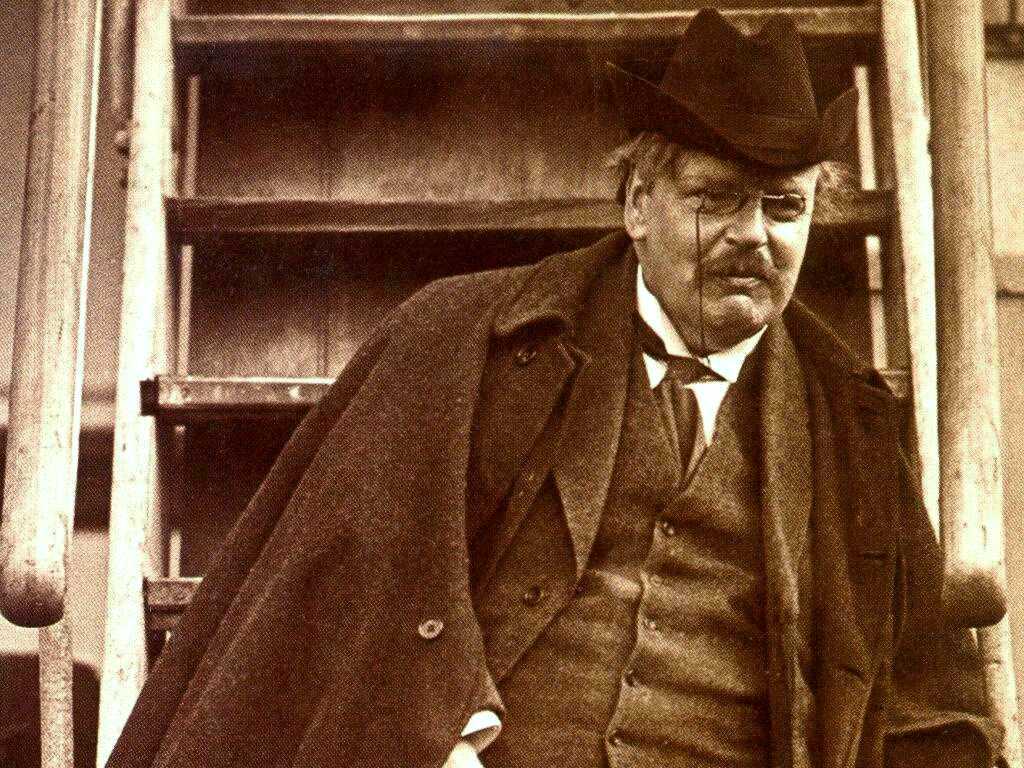

Mecosta, MI. Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) is one of the best known and best loved English wits of the last century. Raised in a respectable English liberal household, he attended the famous Slade School of Art and became involved in liberal politics in his youth; but he was always disturbed by the “lunacy” of his life, that is, its general optimism about human nature and the power of politics that seemed to be founded on nothing more than a bit of middle-class good will. He saw his age as trying to “mean well” but believing in nothing, his society had a big heart but located in the wrong place, and its drumming beat expressed a deafening and indeed bullying confidence in material and moral progress without ever asking, “progress toward what?” Above all, he saw that the most advanced thinkers of his day were committed to human moral progress but only at the cost of ridding human life of those elements that made life worth living in the first place. Thus, in his thousands of poems, stories, novels, and essays, Chesterton took aim at the emaciated, vegetarian, self-denying secular socialists committed to remaking the world in their own bloodlessly rational image. Against the George Bernard Shaws of the world (including Shaw himself), Chesterton defended the basic goodness of life—its reality as a divine gift, a present to which the only possible sane response was a continuous “Thank you.”

Mecosta, MI. Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) is one of the best known and best loved English wits of the last century. Raised in a respectable English liberal household, he attended the famous Slade School of Art and became involved in liberal politics in his youth; but he was always disturbed by the “lunacy” of his life, that is, its general optimism about human nature and the power of politics that seemed to be founded on nothing more than a bit of middle-class good will. He saw his age as trying to “mean well” but believing in nothing, his society had a big heart but located in the wrong place, and its drumming beat expressed a deafening and indeed bullying confidence in material and moral progress without ever asking, “progress toward what?” Above all, he saw that the most advanced thinkers of his day were committed to human moral progress but only at the cost of ridding human life of those elements that made life worth living in the first place. Thus, in his thousands of poems, stories, novels, and essays, Chesterton took aim at the emaciated, vegetarian, self-denying secular socialists committed to remaking the world in their own bloodlessly rational image. Against the George Bernard Shaws of the world (including Shaw himself), Chesterton defended the basic goodness of life—its reality as a divine gift, a present to which the only possible sane response was a continuous “Thank you.”

He defended the soundness of human reason, above all the intuitions of common sense that tell each person that life is good and meaningful, no matter what the Wellsian materialists, Shavian rationalists, or Nietzschean nihilists might say. Even in our darkest hours the thought bears in close upon us that the world is generous, that is, it gives us things of real value. In an early story, Chesterton wrote of a man who leveled a pistol at the chest of anyone who lamented the burden of existence. The burden grew instantly lighter.

What were the components of a life well lived in gratitude? That is, for what are we naturally grateful? What do we cherish? For Chesterton, the answer could be summed up as “for everything,” for life, but above all, for all the little things that really populate our lives: particular places, particular relations and intimacies, the small society of marriage and the family, the only slightly bigger family of the nation, and the universal family of the Church that always embraces us—can only embrace us—in the personal clasp of this parish here.

A staunch patriot and nationalist for the English way of life, Chesterton was a life-long anti-imperialist, who presumed that one of the best things about English nationality was that it was his, or our, culture; surely the Indians and South Africans of the world would themselves best appreciate their own culture for the same reason and to foist ours upon theirs would have been to vitiate both. Rather than continuously looking to the future, to the superstitions of progress, to the rational society at last rid of local and tribal allegiances—the idols of modern socialists and liberals with their hatred of all particular attachments—Chesterton tried to sway his countrymen to look back on the life and land they already knew and loved. They would love it even more if they did not have the anxiety and shadow of the need for bigness, growth, further acquisition hanging over them, and that darkness could be dispelled swiftly by the affections that arise from owning a parcel of land and, at the least, planting a garden and sitting by the hearth with those most dear.

As Chesterton notes in his introduction to Orthodoxy, all these ideas he came up with on his own, thinking them new, revolutionary, unheralded—only to discover that they were the basic, orthodox positions of Christianity: Life is a Gift; the universe is built of irreplaceable small, personal attachments; our lives are small but great dramas of good and evil, of reason and unreason; our reason and knowledge are real already at the level of common sense and hardly require the withering “tests” of the modern philosophers. And so, in spite of himself, Chesterton went from being a common-sense liberal in defense of small society and the family to becoming the most celebrated Catholic apologist of the last century. He defended Catholicism, as in the Church and Her Revealed Doctrines, but also he defended “catholicism,” as in the fundamental goodness of everything—from good beer, juicy steaks, and cigars, to children, wives, countries, love affairs, chivalry, one’s neighborhood, fairytales, adolescent melodramas, and the Cross of Christ. He fought for it all with a jovial laugh that tended to silence the withered, ascetic rationalism of the early Twentieth Century—a period Chesterton found, once again, represented in such figures as George Bernard Shaw, the Anglo-Irish playwright, vegetarian, teetotaler, socialist and sometime Mussolini worshipper. Against materialist theories of progress and reason, Chesterton opposed happiness and common sense.

Chesterton’s style made him famous and infamous; his constant presentation of common sense in the mode of paradox, intended to disturb people into rediscovering what they already and always know and love, may strike a new reader’s ears as chatty and dizzying. It becomes clear very quickly that Chesterton’s great joy lay in formulating these purposefully small paradoxes—that, as it were, a healthy soul has a fat body, a big heart loves little things, a joyful heart drinks alcohol just for the sake of joy and not for some “medicinal” purpose, that every man is a hero to his valet, that material poverty does not entail a poverty of spirit, that a good nation is the one that cherishes rather than “spreads by invasion” its goodness, that lasting individual liberty is found in communal attachments rather than in the most “equal” systems of democracy. His constant delight in verbal pirouettes makes him easy to read often but hard to read in large doses.

In the first chapters of Orthodoxy, we find Chesterton seeking to explain the limits of human confidence: there is a misguided confidence proper to the “Maniac,” of one who thinks the human will can demolish and transcend all limitations, but there is also a wise confidence proper to the human reason—one that, in modern times has committed “suicide”—, which affirms that human beings by their nature tend to know what is real, true, and good. That we are so often mistaken should remind us that we can sometimes be correct, rather than sending us down into the darkness of doubt, relativism, and skepticism. Modern man, for fear of being wrong about something, refuses to think about anything, he protests; Chesterton would have us think boldly, trusting that our fellow men, God, and our own sense of reason will correct us when need be. Being wrong, after all, is a part of a complete life—it is its own kind of peculiar gift. Richard Wilbur captures this Chestertonian affirmation amid error in his little poem, “On Having Mis-identified a Wild Flower”:

A thrush, because I’d been wrong,

Burst rightly into song

In a world not vague, not lonely,

Not governed by me only.

For Chesterton the birds of nature were always singing about the rightness of things and so softly correcting modern man’s unnatural despair of the created order and his egregious confidence that he could create by artifice a more perfect order in deliberate violation of the old one. A sympathetic docility before the song of creation, much though it may resemble a submission of the reason, was a means to reason’s just and fruitful exercise. Appropriately, late in life, Chesterton wrote two great books on St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas: one on the humble saint who lived in continuous thanks and praise of God’s creation, the gift of things; and one on the corpulent saint—that Ox of God, as Chesterton called him—who, with keen and reverent reasoning, saw most clearly the nature of nature, as it were, the order of creation and proclaimed with a resonance no man of good will may forget: to be is good, Being is Good.

I have loved the writings of G. K. Chesterton ever since I read the one-volume omnibus collection of the Father Brown stories with an introduction by Auberon Waugh. As someone who has been a lifelong traditionalist conservative with libertarian sympathies, Chesterton’s “Orthodoxy” was instrumental in helping me realize the priority of traditionalism over libertarianism in my thinking. The part of “Orthodoxy” that most spoke to me was the section on the “democracy of the dead”, which helped crystallize the notion of society as something existing across the boundaries of the generations, in which the past truly does deserve a voice on par with that of the present.

This was an excellent tribute to a wonderful author, Mr. Wilson.

Dear James,

This is a good memorial to Chesterton and his humane thought. I particularly appreciate your emphasis on his critique of progressivism, his small-scale patriotism, and his mimetic discovery of human and catholic truths.

Best,

PDH

Comments are closed.

Andrew Brinkerhoff

If I may make a plug, perhaps my favorite Chestertonian story is the anti-dystopic “Napoleon of Notting Hill” (set, coincidentally, in 1984 London) which joyfully weds his localist and romantic impulses. The uproarious first chapter, “Introductory notes on the art of Prophesy” ( http://books.google.com/books?id=KkKo6WYHuf4C&lpg=PP1&dq=napoleon%20of%20notting%20hill&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q&f=false ), is itself worth the price of the book.