If not for the cloud cover that shielded Kokura 65 years ago today, Nagasaki would still be known first and foremost as a capital of Asian Christendom and a cosmopolitan gateway to the West. That was indeed its main claim to fame back in the 16th and 17th centuries, when Catholic daimyo were not uncommon in Japan, Christian peasantry numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and a delegation of samurai traveled to Rome for an audience with Pope Paul V. Even when the alarmed shogunate turned against the blossoming religion, cast out the priests, and drove the faithful into hiding, the city’s connection to Church life was maintained through various martyrs and a large population of furtive senpuku kirishitan – underground Christians. The former group includes the Twenty-Six Martyrs, who were marched from Kyoto to Nagasaki for crucifixion; the latter remained clandestine for over a century, baptizing and catechizing in secret while patiently awaiting the promised return of the fathers.

Of course none of this is what the city is famous for now, for when Nagasaki is mentioned it is the Bomb and not the Cross which comes to mind. Like Hiroshima, Nagasaki has become central to a debate between proletarianized, post-civilizational Tweedledees and Tweedledums, a debate which misses not only the significance of the city’s heritage but that of the bombing to boot. On one hand the use of atomic weaponry is noisily condemned by leftists possessing all the moral credibility of Stalinist poet Pablo Neruda. On the other, it is celebrated by GOP lickspittles who explain breezily that deliberate massacre of civilians is only terrorism when the bad guys do it. Look left or look right, the American mentality resembles ground zero: Sterilized, featureless, and devoid of activity.

Certainly one could never deduce from the modern excuse for intellectual life that the most scathing criticism of nuclear weapons once came from conservative Catholics such as Elizabeth Anscombe. An Oxford professor and accomplished philosopher, Anscombe founded her critique of the atom bomb upon the proposition Choosing to kill the innocent as a means to your ends is always murder. While acknowledging the fog of war, she had little patience for those who would use that fog as an excuse to chuck ethics into the wastebin:

“But where will you draw the line? It is impossible to draw an exact line.” This is a common and absurd argument against drawing any line; it may be very difficult, and there are obviously borderline cases. But we have fallen into the way of drawing no line and offering as justifications what an uncaptive mind will find only a bad joke. Wherever the line is, certain things are certainly well to one side or the other of it.

She also observed the employment of the false dichotomy fallacy on behalf of the bombing:

“It pretty certainly saved a huge number of lives.” Given the conditions, I agree. That is to say, if those bombs had not been dropped the Allies would have had to invade Japan to achieve their aim, and they would have done so. Very many soldiers on both sides would have been killed; the Japanese, it is said — and it may well be true — would have massacred the prisoners of war; and large numbers of their civilian population would have been killed by “ordinary” bombing. I do not dispute it. Given the conditions, that was probably what was averted by that action.

But what were the conditions? The unlimited objective, the fixation on unlimited surrender.

For the modern state, negotiated treaties are shameful. There is no victory short of the enemy grovelling prostrate and awaiting existential reconstruction. Consider the carping against Bush I for not sending troops all the way into Baghdad to “finish the job.”

Anscombe was hardly alone in being a conservative against the Bomb. An equally weighty voice was that of Richard Weaver, who grew up and attended university in Lexington, Kentucky and went on to graduate work at Vanderbilt, where he encountered the Nashville Agrarian philosophical tradition. Like that of Anscombe, Weaver’s thought regarding total war strikes at unquestioned assumptions nowadays held by all devotees of the Americanist religion, Democrat and Republican alike:

The expediential argument for total war is usually expressed very simply: “It saves lives.” I have seen Sherman’s campaign in Georgia and the Carolinas defended on the ground that it brought the war to an end sooner consequently saving lives; the dropping of the atomic bombs upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been excused in the same way.

This argument, however, has a fatal internal contradiction. Under the rationale of war, the main object of a nation going to war cannot be the saving of lives. If the saving of lives were the primary consideration, there need never be any war in the first place… The truth is that any nation going to war tells itself that there are things dearer than life and that it proposes to defend these even at the expense of lives.

As if to emphasize that his criticism is not coming from the left, Weaver makes the now-taboo concept of discrimination a central element of his attack upon decidedly indiscriminate military doctrines. Furthermore, he contrasts the mechanistic, utilitarian mindset with older, more traditional Western ideals:

Although chivalry today is the butt of jokes, it was in fact a magnificent formal development… [it was] in reality an assertion of the brotherhood of man which makes the abstract, windy, and demagogic apostrophes of the present day to brotherhood look empty… The code of chivalry declared that even if you have to fight your fellow man, this does not mean that you place him outside the pale of humanity, nor does it mean that you may step outside yourself.

Even in warfare, and whether you get the best or the worst of it, you conduct yourself in such a way that civilization can go on.

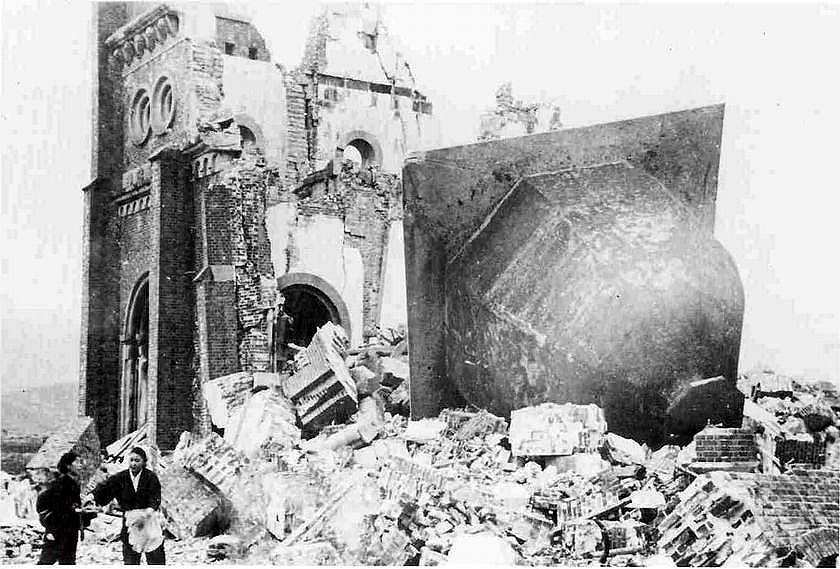

Civilization rests upon the sacred. Thus it is as grimly appropriate that the first atom bomb test was sacrilegiously codenamed “Trinity” – as in the Trinity – as it is that the Fat Man made an almost direct hit upon Urakami Cathedral, the most sacred spot in Nagasaki. It is this point that handwringing humanitarian moralists typically miss: The totalitarian horrors of modern war come from our hubris and impiety, not from any deficit of Lennonesque sentimentality.

An alternative illustration of the impious zeitgeist is the destruction of the Benedictine abbey at Monte Cassino. Founded in 529 by St. Benedict, the time-hallowed abbey was (erroneously) suspected by the Allies of being an outpost for German troops, and was therefore designated a target for a devastating strategic bombing raid. While some had misgivings, an American artillery officer expressed the attitude which eventually carried the day: “I don’t give a damn about the monastery. I have Catholic gunners in this battery and they’ve asked me for permission to fire on it, but I haven’t been able to give it to them. They don’t like it.”

The website of the reconstructed abbey puts the matter in different terms: “[T]his place of prayer and study which had become in these exceptional circumstances a peaceful shelter for hundreds of defenceless civilians, in only three hours was reduced to a heap of debris under which many of the refugees met their death.”

Ironically, once the monastery was obliterated the German hand actually grew stronger, as their forces moved in to find excellent defensive positions among the rubble.

A Southern boy, Walter Miller had been a crewman aboard one of the bombers that had destroyed this one-time home of St. Thomas Aquinas. The tragic Miller would long be haunted by his role in the mission against Monte Cassino, which may even have contributed to his eventual suicide in 1996. Yet during some years of clarity following the war Miller was to become an accomplished science fiction writer of penetrating vision. Specifically, his mesmerizing post-apocalyptic novel A Canticle For Leibowitz draws upon wartime trauma to depict a new dark age following global nuclear conflict. The story is chilling, yet at times humorous and even optimistic as it chronicles the Church’s labors to preserve and renew civilization.

The hagiography of a future scientist-turned-saint named Isaac Leibowitz frames the novel, and seems particularly appropriate to this day:

And the prince smote the cities of his enemies with the new fire, and for three more days and nights did his great catapults and metal birds rain wrath upon them. Over each city a sun appeared and was brighter than the sun of heaven, and immediately that city withered and melted as wax under the torch, and the people thereof did stop in the streets and their skins smoked and they became as fagots thrown on the coals […]

Poisonous fumes fell over all the land, and the land was aglow by night with the afterfire and the curse of the afterfire which caused a scurf on the skin and made the hair to fall and the blood to die in the veins. And a great stink went up from Earth even unto Heaven. Like unto Sodom and Gomorrah was the Earth and the ruins thereof, even in the land of that certain prince, for his enemies did not withhold their vengeance, sending fire in turn to engulf his cities as their own[…]

[T]here was pestilence in the Earth, and madness was upon mankind, who stoned the wise together with the powerful, those who remained. But there was in that time a man whose name was Leibowitz, who, in his youth like the holy Augustine, had loved the wisdom of the world more than the wisdom of God. But now seeing that great knowledge, while good, had not saved the world, he turned in penance to the Lord[…]

In passages written in a more contemporary style, the novel deftly explores the themes of pride and folly without straying too far into the excesses of didacticism. In one striking scene a secular scholar expresses his skepticism of legends about what humanity was like before the nuclear holocaust. Casting his gaze upon a degenerate, vicious and illiterate peasant, he demands of the priest with whom he debates:

Look. Can you bring yourself to believe that that brute is the lineal descendant of men who supposedly invented machines that flew, who traveled to the moon, harnessed the forces of Nature, built machines that could talk and seemed to think?

Could you believe there were such men?

Plaintively and insistently, he asks: “How can a great and wise civilization have destroyed itself so completely?”

Those curious about the priest’s answer will have to read the book for themselves. It’s not a bad question, we must admit, for it prompts us in turn to ask what greatness and wisdom actually are. Such chains of questioning are a prerequisite to any renewal of civilization here in the ruins.

53 comments

Peter B. Nelson

This is a great post. Good on a re-read a year later, unlike most ‘net ramblings.

PMoccia

This article’s main thrust reminds me of a tremendous Evelyn Waugh quotation: “It is no longer possible . . . to accept the benefits of civilization and at the same time deny the supernatural basis upon which it rests.”

Wessexman

Those who speak know nothing, those who know keep silent.

All you can say of God is not true.

I must say I do not claim to be a mystic myself, I’m an exoteric and likely always will be. Like C.S. Lewis I bow to those who are fully awake.

Stewart L

If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.

Too many words.

Wessexman

The Eastern Orthodox theologian whose name I left out is James Cutsinger who is also a noted Perennialist.

Wessexman

Note there are Christian equivalents of Sufism even if they do not form so cohesive a school of thought. The Eastern Orthodox theologian realised a wonderful volume called Not of this world which was an anthology of Christian mysticism. Even ignoring simple Christian Platonists who may not have been practicing esoterics there are all sorts of legitimate mystics in Christianity from the Desert fathers and some of the Eastern church fathers to Eastern Hesychasm and the followers of Gregory Palamas. Certainly Eastern Christianity has been a richer ground for Christian esotericism than the West but the West has not been left out. It has the love mysticism of St.Francis of Assisi, the passion mysticism of a St.John of the Cross, the Rhinish mysticism of Meister Eckhart(perhaps the greatest of all Christian mystics.) and his followers as well as Protestant mystics like Jakob Boehme and William Law and even a few more eccentric, though I still think valid, mystics like Coleridge and William Blake.

Wessexman

“Entertainingly enough, that’s actually very close to what I believe. My secularism comes from the fact that, given the scale of the universe, I have serious doubts as to whether God, whoever he is, really cares about us yet.

I’m interested–do you consider yourself a Christian? I’ve noticed some Sufi references above–are you sympathetic with that line of thought?”

I’m a Christian Platonist and a traditional Christian. I’m also a follower of the Perennialist/Traditionalist school of Frithjof Schuon, Rene Guenon, Seyyd Nasr and others. Perennialists accept the validity of the great, orthodox religious traditions and revelations according to metaphysics or a metaphysical framework of Platonism/Pythagoreanism, Vedanta, Sufism, Buddhism and Taoism, all of which are extremely close in essentials. We believe though it is essential to follow a particular tradition or revelation fully, we are certainly not syncretists. Perennialists place prime importance, like Plato and Shankara, on the Intellect(or in the dharmic tradition Bodhi.) or direct spiritual intuition whereby knower and knowledge are fused, over reason or discursive thought and sensual experience which maintain the divide between knowledge and knower. But the likes of Schuon are masters of logic and discursive thought to a degree in excess of any modernist philosopher. We consider the different genuine religious revelations as collective Intellections.

Wessexman

“If not being well versed in philosophy, metaphysics, and theology made you worthless as a scholar, you’d still be riding a horse and enjoying a life expectancy of forty years. ”

Hello and welcome to Frontporchrepublic. 😉 Dawkins is a worthless scholar.

“1. That’s the point. An acorn becomes a tree, because becoming a tree is the way it interacts with the system. Evolution works the same way, just over a longer period of time. Every generation changes slightly; that’s why you can do things like breed specific stock to different functions.”

You miss the point. It becomes a tree because it is a tree, because it has the possibility within itself of being a tree.

“2. Again, a misunderstanding of entropy. There are laws, and those laws create complexity, just as in the formation of a crystal. Once energy is expended, complexity begins to fail, but it hasn’t been yet, and so complexity remains.”

Yes but you are claiming these laws exist despite the fact that generally complexity will tend to degrade. I see no reason to accept some randomly inserted laws unless you can prove them.

“3. I suggest looking closer. There’s a good reason, for instance, that we use certain animals to test human medications.”

Utter reductionism. You see some similarities and because of social conditioning you remove even consideration of most else. This is why most accept evolution.

“The original quote was from Daniel Dennett, but it has been echoed by a number of top scientists in their fields. But, as you said, you probably don’t consider them great.”

I certainly do not consider Dennet great, he was one of the prime people I had in mind when I talked of reductionism. He wrote a work called Conscious explained which has accurately been dismissed as Conscious explained away. This is another problem I pointed out in evolution and materialistic science; it explains things away as Michael Polyani put it rather than explaining them. Consciousness and life are said to be explained by physics and chemistry by biologists but are simply dismissed. You say you judge things by the empirical or what you see but you are so indoctrinated by materalistic reductionism and just plain nonsense that you do not realise you are explaining away the very awareness with which you gain this empirical data. If one must try and stay very much at the sensual level then they should at least give equal place to consciousness in their thought as external factors(though of course this would tend to move one beyond the sensual world and is deadly to materialism.).

Tim R

Entertainingly enough, that’s actually very close to what I believe. My secularism comes from the fact that, given the scale of the universe, I have serious doubts as to whether God, whoever he is, really cares about us yet.

I’m interested–do you consider yourself a Christian? I’ve noticed some Sufi references above–are you sympathetic with that line of thought?

Wessexman

Btw I’m only a monotheist if that term is understood with an amount of nuance. There is a certain ontological discontinuity between God, or the divine essense, as unmanifest, at least from our relative perspective, and the universe but the universe or relativity is still a part of the infinite possibilities and substance of God. There is not other than God ultimately. This could be understood as monotheism as is certainly not actually contrary to a nuanced but nontheless orthodox position on Semitic monotheism. It could also be called panentheism or even pantheism, if the latter is also understood with nuance and not as simply equating the finite universe with God, but as I said that these terms are not strictly at odds with even orthodox, but nuanced, Semitic monotheism if understood correctly.

Tim R

If not being well versed in philosophy, metaphysics, and theology made you worthless as a scholar, you’d still be riding a horse and enjoying a life expectancy of forty years.

1. That’s the point. An acorn becomes a tree, because becoming a tree is the way it interacts with the system. Evolution works the same way, just over a longer period of time. Every generation changes slightly; that’s why you can do things like breed specific stock to different functions.

2. Again, a misunderstanding of entropy. There are laws, and those laws create complexity, just as in the formation of a crystal. Once energy is expended, complexity begins to fail, but it hasn’t been yet, and so complexity remains.

3. I suggest looking closer. There’s a good reason, for instance, that we use certain animals to test human medications.

4. I tend to agree with you here. That’s why, as I said, I think life might be an actual part of the overall system, and not just a “random accident.”

5. See #4.

The original quote was from Daniel Dennett, but it has been echoed by a number of top scientists in their fields. But, as you said, you probably don’t consider them great.

I’m not sure there’s much point in continuing this conversation, as I think we’re coming from two entirely different places. I focus on what I can see, and therefore on the sciences: genetics, neurology, biology, geology, physics. You approach everything from a metaphysical tack, which is certainly not my strong suit.

Nevertheless, it’s been a useful exercise. Best of luck to you in seeking the desecularization of modernity, even as I do my best to bring it in the opposite direction. 😉

Wessexman

“As to the comments about secular society, you may be right. On a personal level, though, I don’t think you are. As I said, I am myself secular, and am quite happy about it–rather more so, in fact, than I was when I was religious, if only because the universe makes more sense now. I know quite a few people who would say the same, and quite a few “religious” folks for whom the sacred plays no functional part.”

Again you’re missing the point, it isn’t about individualistic opinions but about sociology and culture. Anyway your wrong, you live according to the norms and values of our society which as I showed are intricately linked to the worldview or religion of our society, even though it is now weakening(and predictably society breaking down.).

Wessexman

“I agree that he is philosophically, metaphysically, and theologically illiterate. But Darwinism is not a philosophy, a metaphysical theory, or a theology. It is an extremely major influence, of course, as was in some ways Newton’s laws, but it is not in itself any of those things. The reason is simple; it’s merely a way of explaining what we see with our eyes. The most obvious evidence to me is the way you can trace bits of genetic code from individuals back through family lineages to places, and on into the ancestors we share with bonobos and chimpanzees, all the way back.”

So now Dawkins is worthless as a scholar? I fully agree. Anyway this “evidence” is but excepting social biases. Social biases tell us materialism is correct and hence you believe you are accepting the evidnece of your eyes.

“1. A greater cannot come from a lesser

You’re assuming that’s what evolution is; it isn’t. It’s a system, operating within a much larger system, that, with the constant application of energy (from the sun), leads to increasing complexity. Note that we can see similar kinds of effects by leaving vats of salt water in the sun (forming square salt crystals), or by observing complex orbital systems that form from vast clouds of hydrogen. So, this is “a greater” coming from “a lesser” any more than a star is greater than it’s birth cloud, an adult is greater than the child she once was, or a flash flood in the desert is greater than a cloud.”

This doesn’t answer the question. How can the greater come from the lesser? An acorn becomes a tree because it is a tree, it is part of the larger possibilities of a tree. Only if there was already the possibility, the idea, of the greater existing would your argument make sense but then you’re beyond materialism and standard Darwinianism. You have no answered that question.

“2. Physical (entropy). Again, complexity tends toward degradation in a closed system unless energy is constantly applied. The sun is still burning. Entropy kicks in when it quits. It isn’t disorder, either. Evolution, like gravity, happens according to some very strict physical laws (in these cases, mostly chemical) what results is not “chance” or “chaos” as so many opponents of the theory seem to believe. It is merely, again, the functioning of the system. A bomb or the infamous “tornado in the junkyard” is chaos; evolution is not. Again, a study of genetics and of the building blocks of life is useful on this point. You’re right in saying that we don’t know how life began, but as I said in a previous comment, a few hundred years ago we thought epilepsy was caused by demons. Who knows what we will know tomorrow? It’s human nature to simply assume that God/supernatural forces are responsible for things we can’t yet explain, but not very good practice.”

There problem is this is about a lot more than solar energy, it is about the apparent order in the system, entropy should set in but it doesn’t, in fact even more complex life forms are formed. This does not answer the question.

“3. Biological. Again, look into genetics. I can’t really give any evidence more obvious than that.”

There is precious little evidence that isn’t open to other interpretations that I have seen. So that question is unanswered.

“4. Statistical. The obvious response here is that if life were to happen in one place out of billions, in one universe out of billions, etc., of course the life that evolved there would think itself special because of it. Roll a number between one in a trillion, and the odds that you would roll that exact number are (say it with me) one in a trillion. I’m not really comfortable with this theory myself, which is why I suspect there is something more systematic at work here. Again, as I said, I’m somewhat pantheistic; it wouldn’t entirely surprise me if Life was part of the natural functioning of the universe.”

Firstly the statistics are for the universe so that doesn’t answer the question. Also it keeps happening, evolution hasn’t beat the most tremendous statistics once but over and over again. This leaves the question unanswered at least in anything like a satisfactory way.

“But then again, Monotheism runs into problems here too. As you said, aliens only pushes the problem back a step, but of course, so does God. “The lesser cannot come from the greater” means, of course, that God is more complex than the universe. In this point we are at a deadlock, for one has either to explain the existence of God or the existence of the universe. (And when you reply that the universe has a limited age, please keep in mind that I am talking about this universe. A look into recent works in physics will reveal some very interesting multiple-universe theories that, I think, make a lot of sense).”

Firstly this is strictly irrelevant if we are only talking about what must be in our universe, it makes no difference what we know or don’t know about higher levels of being to knowing they are there. The same goes for this debate, I can see that a materialist basis for life is inaccurate and a spiritual one accurate without realising the full basis of correct theology. Also it is theologically and metaphysically inaccurate to treat the subject that way but I suppose that is a different argument and debating about God’s nature is not strictly relevant and is one of the poorly put questions of Dawkins. So the question is unanswered.

“5. Teleological. Again, we’re not talking about chaos here, we’re talking about evolution. This is one of the ones that used to bother me the most before I learned more about genetics and evolutionary theory. Evolution in this way is like general relativity; it makes less sense the less you know about it. Unfortunately, it’s much (much) too complex to get into here. I hate to harp on Dawkins, but he is one of the few popularizers of the theory–take a look at “Blind Watchmaker”.”

You know every mention of Dawkins lowers your stock right?;) And that question remains unanswered because you, like Dawkins no doubt, misunderstand it. What is being said is, aside from the unsatisfactory assumption that blind evolution could have created Hamlet, is the doctrine of adequetio implies the inaccuracy of evolution. This is best understood in its purest form of the subject-object divide. One makes no sense without the other.

“I understand you have some problems with Darwinism, and maybe that’s because your background in philosophy, metaphysics, and theology has given you some insight that I don’t have. But one way or another, please don’t dismiss as simply absurd a theory you don’t completely understand, and which some of the greatest minds of our generation have called “the greatest idea anyone has ever had.””

What great minds? I probably do not consider them great, anyway I do not simply dismiss evolution rather I understand it as being flawed and inaccurate.

Tim R

As to the comments about secular society, you may be right. On a personal level, though, I don’t think you are. As I said, I am myself secular, and am quite happy about it–rather more so, in fact, than I was when I was religious, if only because the universe makes more sense now. I know quite a few people who would say the same, and quite a few “religious” folks for whom the sacred plays no functional part.

I rather think the idea that a society without a God will crumble is akin to saying a child without a parent will go astray. It’s true, of course, but only up to a point. At some point the child will have to grow up.

Tim R

I agree that he is philosophically, metaphysically, and theologically illiterate. But Darwinism is not a philosophy, a metaphysical theory, or a theology. It is an extremely major influence, of course, as was in some ways Newton’s laws, but it is not in itself any of those things. The reason is simple; it’s merely a way of explaining what we see with our eyes. The most obvious evidence to me is the way you can trace bits of genetic code from individuals back through family lineages to places, and on into the ancestors we share with bonobos and chimpanzees, all the way back.

I didn’t really want to do this, but here goes.

1. A greater cannot come from a lesser

You’re assuming that’s what evolution is; it isn’t. It’s a system, operating within a much larger system, that, with the constant application of energy (from the sun), leads to increasing complexity. Note that we can see similar kinds of effects by leaving vats of salt water in the sun (forming square salt crystals), or by observing complex orbital systems that form from vast clouds of hydrogen. So, this is “a greater” coming from “a lesser” any more than a star is greater than it’s birth cloud, an adult is greater than the child she once was, or a flash flood in the desert is greater than a cloud.

2. Physical (entropy). Again, complexity tends toward degradation in a closed system unless energy is constantly applied. The sun is still burning. Entropy kicks in when it quits. It isn’t disorder, either. Evolution, like gravity, happens according to some very strict physical laws (in these cases, mostly chemical) what results is not “chance” or “chaos” as so many opponents of the theory seem to believe. It is merely, again, the functioning of the system. A bomb or the infamous “tornado in the junkyard” is chaos; evolution is not. Again, a study of genetics and of the building blocks of life is useful on this point. You’re right in saying that we don’t know how life began, but as I said in a previous comment, a few hundred years ago we thought epilepsy was caused by demons. Who knows what we will know tomorrow? It’s human nature to simply assume that God/supernatural forces are responsible for things we can’t yet explain, but not very good practice.

3. Biological. Again, look into genetics. I can’t really give any evidence more obvious than that.

4. Statistical. The obvious response here is that if life were to happen in one place out of billions, in one universe out of billions, etc., of course the life that evolved there would think itself special because of it. Roll a number between one in a trillion, and the odds that you would roll that exact number are (say it with me) one in a trillion. I’m not really comfortable with this theory myself, which is why I suspect there is something more systematic at work here. Again, as I said, I’m somewhat pantheistic; it wouldn’t entirely surprise me if Life was part of the natural functioning of the universe.

But then again, Monotheism runs into problems here too. As you said, aliens only pushes the problem back a step, but of course, so does God. “The lesser cannot come from the greater” means, of course, that God is more complex than the universe. In this point we are at a deadlock, for one has either to explain the existence of God or the existence of the universe. (And when you reply that the universe has a limited age, please keep in mind that I am talking about this universe. A look into recent works in physics will reveal some very interesting multiple-universe theories that, I think, make a lot of sense).

5. Teleological. Again, we’re not talking about chaos here, we’re talking about evolution. This is one of the ones that used to bother me the most before I learned more about genetics and evolutionary theory. Evolution in this way is like general relativity; it makes less sense the less you know about it. Unfortunately, it’s much (much) too complex to get into here. I hate to harp on Dawkins, but he is one of the few popularizers of the theory–take a look at “Blind Watchmaker”.

6. Relativistic. I’m afraid this bit misunderstands the meaning of the word “relative”, and of it’s relation to evolution. Let me make myself clear: just because there might be no moral “Truth” (which would, regardless, only be true in atheistic evolution) doesn’t mean there is no actual truth. There is nothing relativistic about “that tiger is attacking my children,” or “I need the meat of that mastadon to survive.” Those things are true. More importantly, those things are useful. The human mind is entirely unable to comprehend anything close to “the whole truth,” for to do so would require it to be more complex than the system it was attempting to understand. So, we build models. Models are not so much true as much as they are useful. Explaining the sunrise by chariot is one such model, since disproven. Newton’s gravitation is a very accurate model that is nevertheless not quite “true,” because it doesn’t work at small scales, high speeds, or large masses. Einstein’s relativity, the next model in line, seems to be true, but that may be because we just haven’t found anything better. The same line of reasoning goes for Darwinian theory.

I’m afraid you’re confusing evolutionism with postmodernism, which is, I think you’ll agree, a rather spineless approach to take to life, and one which most evolutionary theorists past and present would heartily disagree with. I agree that the “nothing is true” statements of postmodernism are absurd. However, they don’t apply to evolution. In fact, trying do discount masses of geological, genetic, and biological evidence with a linguistic trick strikes me as a bit absurd in itself.

I understand you have some problems with Darwinism, and maybe that’s because your background in philosophy, metaphysics, and theology has given you some insight that I don’t have. But one way or another, please don’t dismiss as simply absurd a theory you don’t completely understand, and which some of the greatest minds of our generation have called “the greatest idea anyone has ever had.”

Rob G

“I have never read…Weaver”

Oh, the shame of it! Proceed immediately to your local bookshop or library and obtain a copy of ‘Ideas Have Consequences’ without delay.

Rob

Wessexman: It doesn’t seem that we have much more to discuss, as, ultimately, I agree with your critiques of Girard. I do not, however, think they are grounds for dismissing his work.

Meanwhile, you’ve given me some fascinating additions to my reading list.

Wessexman

I also managed to drag half a sentence into the wrong place these two paragraphs should read:

“When it comes to the love question I don’t think you have quite grasped my argument. I don’t think I’m incorrect in thinking you aren’t a regular commentator at this site or follower of a traditionalist political and social position? So you may find some of my position strange then, like evolution atomistic individualism comes automatically to many today; liberals, socialist, libertarians and even many conservatives accept much of it without thinking. It is also worth noting that Dawkin’s arguments are often very much influenced by liberal ideology even though he doesn’t seem to understand this. A lot of what he says on say the history of religion and religious societies and society and culture in general would seem silly to even an atheistic or agnostic conservativeing. Polybius, Hobbes, Bolingbroke or Hume for example at least grudgingly admitted the social place of religion

I do not reject a( partly)rational basis for love in the abstract but what I was talking about was the relationship between worldviews or in other words the largely cohesive system of cosmological, doctrinal, spiritual and ethical beliefs and values of a people(ie the Christian or Islamic or traditional Chinese or so on.) and their society, culture and social associations. I was pointing out that not only is society extremely complex, made of up intertwined functions, ideas, statuses, associations, roles and so forth to form a matrix far beyond the complete individual understanding but that these factors that make up society are influenced by and influence the worldview I just mentioned in a myriad of ways, many of which again are beyond our full understanding as individuals. This is but a working out of standard traditional conservative ideas of society and culture and does not necessarily have to be wedded to a belief in transcendence.”

Wessexman

Man I wish I wrote my posts more systematically. There are a few sentences in the above which I started then I jumped elsewhere without remembering to finish the last sentence. Anyway it should be obvious where I did that but sorry if it is hard to read sometimes. Plus I really need to proof read my posts.

Wessexman

I have read Dawkins and he is philosophically, metaphysically and theologically illiterate(not to mention historically, sociologically and psychologically.), he certainly does not answer those questions and nor do other evolutionists. Reductionist “explanations” that avoid the questions are not answers. I skimmed Dawkin’s God Delusion and it was frankly terrible, his response to St.Anselm’s argument for God for instance was quite frankly laugable. Hitchen’s is smarter than Dawkins and more versitile but his work is still little better in quality.

Again Darwinian explains few of those things you are referring to or at least does not prove its explanation and its explanation is often weak. I do think you have swallowed the likes of Dawkins and evolution without realising how much is a social bias for looking at these things through the evolutionist’s lens. Hence you automatically leap Certainly Dawkins and few others answer most of the major philosophical problems in their theory, they explain them away as Michael Polyani said. That is why much more serious philosophers, certainly than Richard Dawkins(though that is perhaps not hard, James Wilson’s recent essay on this forum far outclassed all I have seen from Dawkins) like Dr.Nasr and even those like Michael Polyani and Karl Popper, who I otherwise have little time for(except some of Polyani’s work on tacit knowledge.), keep asking them. They don’t answer them because they cannot be answered, materialism is ultimately wrong or as wrong as any theory can be. The general answers that someone like Dawkins will give you will be laughably inaccurate and probably consist of irrelevant, poorly put questions that are more attacks on a strawman Semitic creationist position than any serious defense of a materialistic theory of life despite it obvious gaping flaws. Really evolution relies on being the only suitable answer for the ideological climate of modern science and society, if it didn’t have the automatic right to be viewed as the best answer it would have been torn apart long ago.

If there is a work I’d suggest you read it is Frithjof Schuon’s Logic and Transcendence. Schuon was probably the greatest metaphysician and religious thinker of the 20th century and that truly is a seminal work.

When it comes to the love question I don’t think you have quite grasped my argument. I don’t think I’m incorrect in thinking you aren’t a regular commentator at this site or follower of a traditionalist political and social position? So you may find some of my position strange then, like evolution atomistic individualism comes automatically to many today; liberals, socialist, libertarians and even many conservatives accept much of it without thinking. It is also worth noting that Dawkin’s arguments are often very much influenced by liberal ideology even though he doesn’t seem to understand this. A lot of what he says on . Polybius, Hobbes, Bolingbroke or Hume for example at least grudgingly admitted the social place of religion

I do not reject a( partly)rational basis for love in the abstract but what I was talking about was the relationship between worldviews or in other words the largely cohesive system of cosmological, doctrinal, spiritual and ethical beliefs and values of a people(ie the Christian or Islamic or traditional Chinese or so on.) and their society, culture and social associations. I was pointing out that not only is society extremely complex, made of up intertwined functions, ideas, statuses, associations, roles and so forth to form a matrix far beyond the complete individual understandsay the history of religion and religious societies and society and culture in general would seem silly to even an atheistic or agnostic conservativeing but that these factors that make up society are influenced by and influence the worldview I just mentioned in a myriad of ways, many of which again are beyond our full understanding as individuals. This is but a working out of standard traditional conservative ideas of society and culture and does not necessarily have to be wedded to a belief in transcendence.

So I was not so much talking of love as a universal quality in my first example on marriage but on marriage as one institution and examining some of the parts played by the culture worldview or religion in that institution. I was saying that a couple gets married partly to fulfil social norms(roles, ideas, functions and so on.) which they themselves certainly have not constructive and certainly do not fully understand in a rational way. I was then pointing out that in the case of marriage these norms obviously dovetail with the worldview or religion of the society and culture so that in the West for example our views and norms on marriage have been and are powerfully influenced by Christianity. But again it is important to say individuals do not know just how far Christianity has had an influence on said norms that is partly beyond what we can rationally understand.

Not only is such an argument obviously an impeccably good one for social conservatism but it is also casts doubt upon the possibility of a “secular society”. That is because it seems extremely unlikely, both in theory and from historical example, that a secular philosophy could be broad, organic and versatile enough to create that largely cohesive cosmological, doctrinal, spiritual and ethical system I called a worldview in a satisfactory and healthy way. It seems to me any “society” that tried this would either fall apart or this secular worldview would gradually be converted into something more “religious” or “supernatural”. Secular philosophies are simply too artificial, narrow and rationalistic to robustly fit properly all the rational and non-rational niches in society a worldview or cosmology must occupy, they do not have reach or versitility to properly react with all the social functions, roles, statuses, ideas, associations, traditions and values that they need to to properly provide for a healthy society in the long term.

Psychologically the individual will be let down, the complex mesh of idea and function, morality and materiality that makes up his world be frayed. The layer provided by the cosmologically or worldview or values and beliefs or religion or philosophy of society or whatever we call it will be woefully incomplete and torn not reaching to the periphery and with gaping holes even in the centre.

Tim R

I’m familiar with those objections, and will honestly say that the theory has very good answers for all six–which, obviously, are too complex (and long) for the scope of this discussion. Whatever else you may think of Richard Dawkins, I suggest reading him if only to hear the (very good) arguments strict atheists will present on to the objections you’ve noted. I agree with him on those points, for the most part, but am not quite so much a zealot. And, I’m sorry for misunderstanding your position: coming from that background, I’ve become rather too accustomed to assuming young-earth creationism the moment anyone mentions an alternative to Darwinian thought. I could certainly see the species-explosion theory as being a primary mode by which evolution could take place, especially as evolution seems to happen in response to changes in conditions, which may happen rather rapidly. But I’m getting carried away.

I absolutely agree with you that love is not rational. I’m not saying that it is; I’m saying, rather, that there are rational explanations for human irrational (or supra-rational) emotions and acts, such as love, hate, altruism, etc. Dawkins again is useful there, with his seminal work “The Selfish Gene,” which has the added advantage of being written during his pre-antireligious-zealotry days.

The main thing I can’t explain is beauty itself. Physics, mathematics, and Darwinian theory are all well and good, but the fact that those things can be beautiful is another thing entirely. I would say that’s the main reason I’m, as stated, Pantheist and not atheist.

I’m interested to see if that’s true, about secular societies. Those few attempts at explicitly creating them have indeed failed miserably, but of course, those societies (ie Russia et al) were so antireligious and ideological as to be, practically speakings, as “religious” as any theocracy.

I suspect the next few centuries may show something different, but who knows. We humans may be unable to formulate a truly secular society whether the sacred exists in actuality or not. Here’s hoping a longevity vaccined is developed soon; I’d prefer not to miss the next few centuries of human development.

Wessexman

“I’m somewhat sympathetic–unlike a Dawkins, say–to the young-earth Creationist idea, because I was one once myself, and quite an ardent one at that. The mistake I made was deciding to look into the opposing side. The evidence convinced me, and everything I’ve found since then in my research into genetics, anthropology, geology, astronomy, and paleontology has only served to reinforce the strength of the theory in my mind.”

This is certainly not what happened to Dr.Nasr. Nor has it convinced me, though I do need to do more reading, and like Dr.Nasr I’m more struck by the evidence evolutionists explain away like the sudden “explosions” of species rather than clear evidence for evolution. I’m not though, nor have I ever been, a Young earth creationist. The world is clearly a lot older than 6,000 years.

Interestingly these empirical problems with evolution are far more open to interest outside the Anglo world. Whereas in the Anglo world evolution is an ideology that treats any sort of criticism, such as biologists who formulate theories of instant or explosive evolution to explain things like the Cambrian explosion.

Wessexman

Tim the problem is there are major philosophical and metaphysical problems with Darwinianism which is one reason it doesn’t actually explain those areas you talk of. This article is a very brief description of what, as it says, are six fatal flaws in the evolutionist perpective:

http://worldwisdom.org/public/viewpdf/default.aspx?article-title=6_Fundamental_Flaws_in_Evolutionist_Hypothesis_by_William_Stoddart.pdf

There are other philosophical flaws as well such as the one Michael Polyani pointed out, that evolution doesn’t explain how life came from non-life or conscious from non-consciousness or even what life or consciousness is. As he said some posit that you go to physics and chemistry to answer these without realising that this explains nothing. This is related to the obvious and massive reductionism inherent in the evolutionist and related explanations. In fact the “explanations” of such people are usually as much about explaining away as explaining whether it be consciousness or whatever. So their insights on such topics as you mentioned hardly seem to worth much to me. There is nothing exciting about such people unless sophistry is to become exciting. Daniel Dennett is obviously a major exponent of such nonsense as is Susan Blackmore.

Anyway when you talk about rationally explaining love you are confusing my meaning. I presume you come on this board because you have some relationship to the conservative, decentralist ideology which makes your comments on that subject strange to me. I was not making metaphysical or religious points in that part of my argument and in fact an atheist or agnostic could completely agree with me there. What I was suggesting is such concepts as, if you will love, in a society are not completely based on rational opinions devised by living people in the society and fully understood by all. Society is so complex with its intertwining of functions, ideas, roles, traditions, beliefs, values, statuses and so in a matrix far beyond the full understanding of individuals that we cannot really completely understand the role of particular worldviews or belief or values in the society. This is but a fuller working out of common traditionalist-conservative perspectives(check out Edmund Burke or Russell Kirk or Robert Nisbet.) and is not necessarily dependent on any transcendental support. You haven’t really replied to this.

My slightly more controversial point is that a secularist worldview could not replace the organised worldview or religious culture of a society because it wouldn’t have the organic and wide nature of a genuine religion and hence provide for all the diverse and far beyond the rationally understandable areas, such as ideas, functions, roles and so forth in their entirity, within that society. Hence no healthy society has been secularised or even mostly secularised. Again on its own this doesn’t have to be connected to a viewpoint on whether or not the worldview of a culture is really linked to anything transcendent. Indeed I suggest even if you started off trying to make a secular society its values and beliefs would eventually take on supernatural elements or the society would fall apart.

Wessexman

Thanks for that article Rob G. It does seem to confirm my first thoughts about Girard. He may himself escape the danger, though I doubt it, but there is too much to be lost and too little to be gained by this use of or compromise or dialogue with post-modernists, structuralists, post-structuralists and so on. But as I said in the post awaiting moderation I’ll keep a more open mind than I would otherwise because of my deference to the intelligent commentators on this site.

When it comes to Guenon he is an excellent writer though unlike Girard he is not trying to come up with much original(beyond a reformulation of the sophia or religio perennis perhaps which evolved into the doctrine of Perennialism with his followers which though it has many antecedants has never quite been expounded in this way before.) but to convey traditional metaphysical, cosmological and symbolic insights to modern audiences. Unlike Girard he is an uncompromising opponent of modernism and post-moderism indeed his work The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of our times has quite accurately been described as so powerful a critique of modern society as to make all others pale in comparison. Guenon does have a few foibles though which though, like his hostility to Buddhism, are amply balanced by his fellow travelers like Ananda Coomaraswamy and his followers like Titus Burckhardt(a great newphew I believe to Jacob Burckhardt.), Martin Lings, Dr Nasr, Macro Pallis, E.F Schumacher(whose more a follower of Guenon’s followers though.)and above all Frithjof Schuon. The latter who in all deference to Guenon surpasses him.

Tim R

In some ways, that’s what I mean. The presupposition there is that some things (love, etc.) cannot be explained rationally. I haven’t decided yet if I agree–that seems to be true, but then again, three hundred years ago the northern lights, thunderstorms, and epilepsy couldn’t be explained rationally either.

The thing is, Darwinism does offer very good explanations for things like religion, morality, and even “spiritual” experiences. Those theories have been backed up recently by recent neurological research into the human spiritual experience. It’s still all highly controversial, of course, but what I’ve seen so far is quite convincing. Olaf Blanke is one such experimenter to look into.

I’m somewhat sympathetic–unlike a Dawkins, say–to the young-earth Creationist idea, because I was one once myself, and quite an ardent one at that. The mistake I made was deciding to look into the opposing side. The evidence convinced me, and everything I’ve found since then in my research into genetics, anthropology, geology, astronomy, and paleontology has only served to reinforce the strength of the theory in my mind.

There are certainly some philosophical problems with Darwinism. However, I suspect these could be solved comfortably by positing a sort of pantheist (a la Einstein) worldview, where the natural processes of the universe, including the Darwinian progression of life, are part of the divine path.

There is also, of course, the possibility that there is no such higher order, or, if there is, that it just doesn’t care about us. This causes a number of problems and may well lead to an unstable society if the majority were to believe it–but of course, the truth is not always comfortable.

I would say I’m closer to a pantheist than an atheist at the moment, but if I’m to be perfectly honest I would say the sacred plays no important role in my life; or, conversely, that all parts of life I see are equally sacred. The more I learn about the wonders of the real, visible, experiential world, the less I need to find some supernatural meaning behind it. The universe is a spectacular place that our human tales of angels, demons, djinn, houris, and gods simply pale in comparison to.

Wessexman

Rob I gave an answer to your post but left the man out of my username so it is awaiting moderation.

Tim I don’t think it is just a matter of presupposition. The none metaphysical and cosmological comments I made stand including my points of the relationship between the worldview granted by a religion and the ideational and functional matrix of a society, culture and social associations. This stands even if one rejects any transcendental validity for such a worldview. Human relationships still exist only within a complex, intertwined partly pre-rational framework of functions and ideas which intersect with a culture but not completely in understandable ways. I still get married not just because I fancy a girl and then I totally invent a possible structural relationship for us but because of certain ideas about relationships, sexuality, gender roles and so forth which are current in our society and which dovetail in many places, though not always in rationally understandable ways, with the worldview or spiritual tradition of the society and culture.

And finally it still stands that no healthy civilisation or culture has ever existed that has been secularised or largely secularised and it seems extremely unlikely that such a wide, gradual, organic and only partly rational secular replacement for religion. Secular society is therefore an oxymoron without even investigating metaphysics, theology and cosmology.

You could argue that there is some presuppositions in the last point ie that a secular culture must be too narrow, artificial and rationalistic to ever create a healthy culture but as far as I can see to make this point you’d have your work cut out to shows secularism could be otherwise.

When it comes to Darwinianism I can turn the tables on your comment. Darwinianism has changed so much that really its only coherent definition is that there is a naturalistic origin of life and humanity. Contrary to Richard Dawkins I do not believe we should presuppose such an explanation as obvious unless overwhelming “scientific” evidence shows otherwise. For one reason not to accept such a preposition check out this wonderful speech of Seyyed Hossein Nasr called “In the Beginning Was Consciousness”:

http://redirectingat.com/?id=673X542464&xs=1&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.hds.harvard.edu%2Fnews%2Fbulletin%2Farticles%2Fnasr.html&sref=http%3A%2F%2Ftraditionalstudies.freeforums.org%2Fquestion-about-sri-aurobindo-huston-smith-and-evolution-t414-10.html

Anyway when I say I reject Darwinianism that does not mean I believe the empirical necessarily proves Darwinianism and I reject this along with it. I fully admit to not being an expert on such evidence but from my own investigations and readings of scholars who hold traditional religious views and yet know a lot about evolution and its supposed evidence, and I mean people like Dr.Nasr who is an internationally recognised authority on Islam and Sufism and who was delivered that speech on invitation to Hardvard and is clearly no YEC obscrurantist, I do not believe the evidence for Darwinianism is conclusive(by far.) and I believe it has the status of basically an ideology in he Angl-American world which interestingly it doesn’t have, though it is still accepted, outside it. This is besides the massive metaphysical, philosophical, theological and mathematical problems with Darwinianism.

Wessex

“His reductionism isn’t the sort that seeks to eliminate the supernatural or metaphysical from the universe but rather the kind that seeks to reduce an anthropological theory to that which is anthropology’s appropriate subject: the empirically (scientifically) observable aspects of human society, behavior, and nature.”

The problem Rob is that such a methodology is always full of danger, unless one is extremely circumspect and if his wiki is anything to go this is what happened to Girard. He took one bit of human religion and behaviour and becuase he didn’t ground it in traditional metaphysics and cosmology he seems to have misread it because he is too influenced by erroneous modernist(or post modernist) ideas and expanded it to levels it does not deserve. Again it is only the wiki but I didn’t see much on it to make me want to take a keener interest in Girard and I’m someone for whom religious and comparative religious studies is very important but in deference to my good opinion of those posting on this site I will keep an open mind on this fellow.

Personally I’m not that worried about dialogue with post-modernists. Either they understand or they don’t. They ocassionally give some interesting insights on modernism but apart from that they seem to offer very little that would be worth the danger of submerging oneself in their thought(or perhaps anti-thought is the correct term because as the metaphysician Frithjof Schuon put it when talking of such people “it was left to the 20th century not to think and call it philosophy.). But I’m an uncompromising fellow, I cannot think of a post-Descartesian philosopher(at least in terms of that tradition if not necessarily in strickly chronological sense.) that I would advise be read for their own sake. Again with Schuon I agree when he said if Plotinus(or Plato or Laozu and so forth.) was a philosopher then Descartes(or Hume or Kant or Bertrand bliming Russell or in many ways even the likes of bishop Berkeley and his school.) was not.

Tim R

I suppose that makes sense, then. If you are going to reject Darwinism, you have no choice but to choose supernatural (and sacred) bases for all of existence. I’m just not sure rejecting Darwinism, and empirical evidence, over the old metaphysical modes of thought is a viable option.

At that point it’s just a matter of presupposition. All further conclusions, including definitions of a good society, come from those presuppositions, and all arguments must rest on which course you first choose t o follow.

Rob G

Both Rene’s, Guenon and Girard, are well worth reading. Here’s an article/interview with the latter from a few years back in Touchstone.

http://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=16-10-040-i

Rob

Wessexman: I didn’t say I was a partisan of Girard, so I didn’t expect you to convince me to turn from my Girardian ways (especially since you have yet to read his works)! However, I think his theory of mimetic desire and sacred violence (or violent sacredness?) is quite instructive and, at worst, a useful exercise. You are correct to note his aversion to metaphysics and, if he is guilty of anything, it is a structuralist reductionism. On the other hand, he has been able to bring concepts of the sacred and particularly of Christianity into vibrant dialogue with post-modernists and others who are even more averse to “insufferable metaphysics” (as one of my post-structuralist professors has been inclined to state with disgust).

As for myself, I am not prepared to dispense with metaphysical discourse and concepts. But, at least for charity’s sake, we must recall that Girard is an anthropologist (well, his theory is anthropological at any rate), so he is attempting to explain humanity in human terms. Once again, it is a useful exercise as far as it goes. He makes no claim to being a theologian or metaphysician. And I would add that comparing him with Richard Dawkins and his ilk is entirely mistaken. His reductionism isn’t the sort that seeks to eliminate the supernatural or metaphysical from the universe but rather the kind that seeks to reduce an anthropological theory to that which is anthropology’s appropriate subject: the empirically (scientifically) observable aspects of human society, behavior, and nature. So, while his aim is to find “human” explanations for human sacrificial rites, for instance, he makes no claim to strip the universe of God or the gods,as Dawkins does. In other words, he does not fashion of himself a crud Occam’s razor with which to eliminate all but the scientifically “provable” from the realms of what constitutes “truth.” I do not assert that this is the best or the only way of investigating the truth of human order, but it is one valuable method.

(He is a Christian, though.)

Wessexman

Rob I looked into that Rene Girard and I must say if you want a proper French scholar of religion named Rene you’d do a lot better to check out Rene Guenon:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rene_Guenon

Anyway when it comes to Girard he seems to try and explain human relationships with the divine in very modernistic(even post-modernist.) and reductionist terms, rather than showing any familiarity with traditional conceptions of metaphysics, cosmology and such(though I’m only going on the wiki mind you.), for instance his mimetic desire theory makes little sense from a traditional, realist perspective as it seems to pose fundamental rivalry among subjects who are ultimately reflections of the divine and indeed none other than it(as it is put in Vedanta; Atma(self) is none other than Brahman or more informerly “thou art that”.) Also he seems to have a large place for Darwinian evolution in his theories which as a Christian Platonist(the same is true though for all traditional schools of metaphysics.) I reject. Traditionally speaking Species on earth are individualised aspects of their universal essences or ideas, so they cannot transform into other Species. And obviously this also is another reason why Girard’s idea of fundamental conflict is nonsense from the perspective of traditional metaphysics. Conflict in such a perspective is accidental, it arises because of the “distance”, loosely speaking, from the divine.

But the most important criticism must be the reductionist nature of such ideas, they seem little better than say Richard Dawkin’s or Susan Blackmore’s and ignore all the layers of being. Ultimately if one wants to get reductionist, the only way to do it is upwards so to speak, to reduce to the highest level of truth and existence and not to the lowest or in Girard’s case, as different and an improvement on the likes of Dawkin’s, to the lower levels. Such a positive reduction would result in that traditional doctrine best most succinctly expounded, as is often the case, by Adi Shankara(the Hindu Plato.):

“(Nirguna)Brahman is the only truth, the relative world(the universe or Maya.) is an illusion, and there is ultimately no difference between Brahman and the individual self(Atma.).”

But of course even that level of reduction is too much for any but the greatest mystics to work with hence the existence of religions, cosmology, theology, traditional sciences and so on. But anyway I think I’ve ranted enough, I just hate the gall of modern “scholars” who think they have come with a completely new and yet extremely explanatory theory for such things as human society or human religion or whatever as this fellow seem to have.

Wessexman

Tim R you are forgetting that the sacred in its widest meaning refers to morality and cosmology/worldview and is intertwined in ways partly imperceptible to full rational investigation with culture, society and social associations to the degree that no culture or society is imaginable without it. And before someone mentions that a secular viewpoint could occupy the sacred’s place even without going into spiritual or highly theoretical arguments we can point out that such has never happened in human history. The closest that has happened is sick and declining civilsations have somewhat secularised their religious traditions. Also any such completely secular alternative would be narrow, artifical and rationalistic unable to provide for the variety and width of human nature and human society and culture. Certainly I have never seen or heard of a secular, even just a secularised religious culture, ever having come close to properly and healthily replacing a faith in a civilisation. Obviously if we’re talking more spiritually or metaphysically then just about every traditional faith echoes the Semitic monotheistic position that man and indeed the universe, to put it crudely, are made in the image of God. This was as true for Plotinus or Adi Shankara as it was for the Cappadocian fathers or Ibn Arabi. But I suppose that is a discussion best had some other time.

I’m sorry but secular society is an oxymoron, I will not beat around the bush so I don’t place much importance on our “secular”, “pragmatic” society. We’re simply living on the capital of earlier more traditional and therefore spiritual times. In Egypt and all those other ancient civilisations religion, metaphysics, cosmology and morality governed their existences to a large degree. Even their use of material resources would of had a lot to do with traditional sciences like sacred geometry(like the geometry of Pythagoras and Plato which was influenced by the theosophy of Egypt and Mesopotamia.), the traditional doctrine of symbols, alchemy and such.

The sacred was of course as important for nomadic societies as it was for sedentary. I was not really differentiating between them and referring to them both as “civilisations”. There is an interesting transition between the two kinds of civiisations as the nomad lives in space(understood traditionally and therefore sacredly and symbolically as it was certainly for the nomad.) and for him time is little more than a rhythm, whereas for the settled civilisation it is time, linear time, that becomes more and more important. But anyway that again is perhaps enough discussion my main point is that even in such basics cosmology and symbolism played massive, defining roles for traditional civilisations.

I’m very traditionalist, even reactionary Tim the early modern Dutch and post-revolutionary French are no models for me but I still don’t think they were secular rather than having secularised their religious culture somewhat.

Radical Islam or rather more correctly fundamentalist Islam is a modernist inspired remodeling, and indeed distorting some earlier legalist Islamic schools and scholars like the Syrian anti-Sufi polemicist Ibn Taymiyya. But as I said like all fundamentalism Islamic fundamentalism is essentially modernist, it is about turning a traditional religious tradition and revelation into an ideology like Marxism and like Marxism it therefore relies on extracting a few clear and simplistic doctrines from a close and literalistic reading on a few texts. It knows nothing and cares less for traditional doctrines of symbolism, cosmology and metaphysics and hence its veneration of the sacred is very much blunted. We should aspire to remove its recruiting grounds by granting proper soil to real traditional understandings of the sacred and hence squash the two parallels evils of fundamentalist religious, and indeed other branches of modernism faith like “liberal” Christianity, and secularism.

Tim R

Steve: you’re definitely right on that one. However, having less kids actually seems to be a product of civilization itself rather than the loss of religion. The one statistic birth rate is linked most is education, not religion. When you live in a population dense, high-skill economy, like Switzerland, having several children isn’t necessarily a good idea, financially or ecologically. If you come from a more rural, agriculture-based (read: traditional) society, kids are extra work hands, and are an asset.

There are a whole range of issues related to the Islamic immigration tactics into Europe, birthrates among uneducated sectors, and Europe’s population declines, but, again, I’m not sure how much of a role veneration of the sacred plays in it. I suppose you could say that radical Islam is succeeding because it venerates its sacred to such an extent that any violators of it are executed (and you might be right), but honestly, is that something we should aspire to?

D.W. Sabin

Interestingly, reading the Old Testament, one must wade waste deep , sometimes great flood deep through all manner of violent punishments and retributions doled out all around, both chosen and un-chosen experiencing a mighty dose of arse-whuppin. Some of it would have made Hobbes blanche and start sucking his thumb.

Sometimes, with the sacred, one is advised to be transcendent “or else”. The “or else” always seemed to concentrate the mind and lend power to the Satraps of the Sacred.

Steve K.

“If you look at modern societies, I’m not sure a need for the sacred can be properly justified, although the universality issue again comes into play. The Swiss, French, and (especially) the Dutch come to mind as civilizations at least equal to the American religious one, or historic Christian/Islam/Buddhist/Pagan ones, in terms of efficiency, intellectual vigor, and any other characteristics I can think of that a good society might have.”

All three of these societies were quite religious until fairly recent modern times; all three have been losing their religion but are now facing serious demographic challenges, which seriously question the future viability of those societies, at least as Swiss, French and Dutch societies. Others are filling the demographic gaps, but of course those societies will cease being Swiss, French and Dutch in time, and given who is having the babies in those countries, they will be religious societies again (though not Christian, unfortunately).

Rob

Wessexman: My semi-cryptic reference was, in fact, to Rene Girard, as Jason Peters mentions above. Rather than attempt an exposition of his rather complex thesis, I would recommend that you sample a bit of his corpus yourself.

I’m currently wrestling with its validity myself, so I would welcome interlocutors.

Tim R

True enough, but the question remains: is the sacred actually necessary for civilization forming, or merely a byproduct of the universality of the concept at the time? I actually like this essay–Canticle for Liebowitz is, in my opinion, near the pinnacle of recent Christian fiction–but, as a secular soul myself, I’m objecting to the need for the sacred in a productive, “good” civilization, especially in the line of reasoning taken by Wessexman above.

If you look at modern societies, I’m not sure a need for the sacred can be properly justified, although the universality issue again comes into play. The Swiss, French, and (especially) the Dutch come to mind as civilizations at least equal to the American religious one, or historic Christian/Islam/Buddhist/Pagan ones, in terms of efficiency, intellectual vigor, and any other characteristics I can think of that a good society might have.

Part of my objection, though, may be in my definition of sacred. I’m thinking of it in primarily religious terms and in instilled moral values–taboos and the like. I wonder if you have a broader definition? I’m interested to hear what you think as to the role of the sacred in a largely secular, rationalist, and pragmatic society–or if you think such a society can indeed function at all.

JD Salyer

My thanks to Prof Peters for suggesting additional worthwhile reading — that is, Girard, with whom I confess I am unfamiliar.

As for Mr. R’s objection, it might be worth digging into our logic textbooks, so as to reflect upon the distinction between “necessary” and “sufficient.”

Tim R

Wessexman,

While that’s true (at least in Egypt), my point is that the sacred is far from being the sole foundation of civilization. Every single ancient culture, civilization or not, had a sense of the sacred. Those that formed multiple-city civilizations had a more rare set of characteristics, including agriculture, trade, currency, and written language.

In other words, observing that all ancient civilizations included religion in a central role does not necessarily mean religion (the sacred) was responsible for the founding of civilization. It would only mean that if the concept of the sacred was limited to settled, sedentary civilization–which it most certainly wasn’t.

Wessexman

“If you look at the way the earliest civilizations formed in Mesopotamia, China, Egypt, and the Indus river valley, you’ll find that while the sacred existed there as much as anywhere, what really served as the foundation of the first civilizations was good old money.”

That depends on a lot on perspective, those were extremely theocratic(or perhaps societies we should say spiritual societies.).

“Wessexman: What if the sacred is rooted in violence?”

You’d have to explain your meaning here Rob. The sacred is rooted in the higher realms of human nature(leaving aside whether these realms are truly part of or echoes of something transcendent of the material plane.). Violence or rather the ordering of violence has a place there it seems to me but not any Hobbesian view of violence.

Tim R

Honestly, the sacred existed long before what we call “civilization” (ie a structured, non-transient society), existed after it in some cases (North America after the smallpox decimation of Native American population) and often becomes strongest when civilization seems to be threatened (9-11).

If you look at the way the earliest civilizations formed in Mesopotamia, China, Egypt, and the Indus river valley, you’ll find that while the sacred existed there as much as anywhere, what really served as the foundation of the first civilizations was good old money.

Jason Peters

Rob asks a good question, in answer of which we have the fairly compelling work of Rene Girard, who grounds both civilization and the sacred in violence.

I’ll not go into it. His books are available to those with money or library privileges.

A salyutary piece, Salyer.

Rob

Wessexman: What if the sacred is rooted in violence?

Wessexman

I never said you dismissed the possibilities of transcendence Sabin, I simply disagreed with you that civilisation is based on force. Human interaction is partly based on force certainly but the basic foundation of what makes it a society or a civilisation, rather than a chain gang, is the sacred.

D.W. Sabin

No Salyer, I think your original choice of words resulted in an important dissection of meaning. This always comes freighted with the ample baggage of the reader. Your last comment summed up the issue perfectly.

Talk about not being qualified to talk theology, I’m the personification of that . A Shameless Apostate.

Jerry Salyer

Which is the appropriate metaphor for God — the supporting foundation beneath us upon which we must build, or the stars high above by which we steer? Though I am hardly qualified to talk theology, my understanding is that the Church does not hold these metaphors as representing mutually exclusive understandings. God is both — immanent and transcendent.

Perhaps the expression “rests” conveyed unintended associations of slack existence and ease, along with spatial connotations; maybe I should have used the word “depends” instead.

D.W. Sabin

Wessexman,

Aside from missing the point of my statement entirely, you cherry pick and imply that I deny the role of the sacred in helping to build civilization or that I might dismiss the possibilities in transcendence. While I might assert that we are prone to “Hobbesian nightmare” to an unseemly degree, I believe an energetic reach for transcendence is both possible and necessary.

Wessexman

“I’m not so sure that “Civilization rests upon the sacred”. Instead, I believe it rests upon a machinery of violence, from primitive clubs and arrowheads to Drones piloted from Colorado Springs and raining death in Waziristan because 19 dark-hearted sociopathic inductees into a perverse cult flew airplanes into two New York Skyscrapers to kill civilians in a game of geo-political Cat and Mouse.”

That isn’t civilisation though, it is the sacred which allows civilisation into what would otherwise be this primitive relationships of force, that you put describe. Obviously most of us who take the time to notice the sacred underpinnings of society, that culture comes from cult, believe that the sacred is in fact a link to something transcendent or divine and hence would doubly see it as a necessary component of human society indeed human nature and the universe itself but even without going into such arguments we’d still argue that clearly it is religion, or approximations to it, that are the necessary foundations of society, culture and social associations and what stops them ultimately being a Hobbesian nightmare.

Sarsfield

As for the typical knee-jerk response that dropping the bombs was necessary to save lives, it’s worth noting that both Eisenhower and MacArthur rejected this in no uncertain terms. You’d think they, of all people, might have known. Unfortunately, neither of those “leftists” was consulted.

D.W. Sabin