Kearneysville, WV. During this season dedicated to giving thanks, my thoughts—provoked by the calendar and images of contented Pilgrims—turn to gratitude. Even in comparatively difficult times, there is still much to be grateful for. After all, the Pilgrims themselves suffered much prior to and after their meal of thanksgiving.

Kearneysville, WV. During this season dedicated to giving thanks, my thoughts—provoked by the calendar and images of contented Pilgrims—turn to gratitude. Even in comparatively difficult times, there is still much to be grateful for. After all, the Pilgrims themselves suffered much prior to and after their meal of thanksgiving.

A day given to feasting and rest in the company of family and friends is also a day where work (save that required to prepare the meal) ceases. We turn aside from the daily tasks of our lives to feast in the company of loved ones. Yet, what if every day was a feast? What if every day was given to rest, eating, and relaxation (and perhaps even football on the television)? When considered from that perspective, it quickly becomes clear that days of rest and celebration require days given to other things.

This suggests that one of the things for which we should be grateful is work, for bereft of work, a day of feasting and rest is quite meaningless. But what does it mean to be grateful for work? Doesn’t work represent drudgery? Isn’t work the very part of our lives (a significant one at that) where our freedom is subsumed by demands of bosses and deadlines and annoying co-workers? If this is the case, then work is at best a necessary evil and permanent relief from it would represent a stroke of luck comparable to being pardoned from a life sentence.

Yet something about the foregoing seems amiss. We have all known moments where work well done produces such a clear sense of accomplishment and satisfaction that to call this a necessary evil is to deny the goodness that we so obviously know and feel. Could it be that work itself is a good? If so why, despite the satisfaction that occasionally rises to the surface of our experience, do we so often see work as a burden? What is it about work that calls forth such opposing thoughts and emotions?

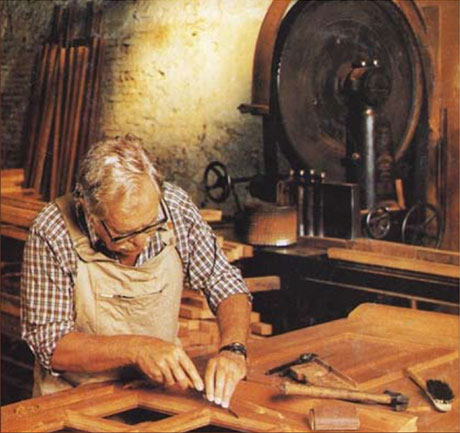

I am currently reading Upton Sinclair’s classic muckraking novel The Jungle. While one thrust of the book is the appallingly unsanitary practices of the meat packing industry, another important theme is the degrading way that workers were chewed up and discarded as disposable means to securing profits for the owners. The overwhelming scale of the meat production industry was made possible by automation whereby individual workers performed one simple and discrete task for ten hours or more each day. Few jobs required any real skill, and most could be mastered in a matter of minutes. Marx criticized the dehumanizing quality of such work when he noted that work in the industrial world is often reduced to a single “knack.” In essence humans were expected to work like simple machines without any attention to the final product they were striving to create. In such contexts, work is stripped of its meaning, for the worker can never experience the satisfaction of completing a final product. He has nothing he can point to and say with satisfaction “that is the work of my hands.” He has nothing to which he can sign his name and thereby express his identity through the product he has created.

One aspect of good work, then, seems to include the opportunity to attend to the whole. It is the difference between integration and dis-integration. Yet even when our work is not simple and repetitive motions in a long line of production, we can still reduce the scope of our attention so our work lacks any larger context and thus remains dis-integrated. According to Wendell Berry, “much modern work is done in academic or professional or industrial or electronic enclosures. The work is thus enclosed in order to achieve a space of separation between workers and the effects of their work….Nevertheless, their work will have a precise and practical influence, first on the place where it is being done, and then on every place where its products are used, on every place where its attitude toward its products is felt, on every place to which its by-products are carried.” This forces us to consider our work in the context of the places we live and the lives we lead. Part of responsible—and therefore truly satisfying—work is knowing that what we produce with our hands and minds is good in the broadest sense. As Berry puts it, “the name of our proper connection to the earth is ‘good work.’”

If, as Berry suggests, there is such a thing as good work, there is also such a thing as bad work. Bad work fails to account for the context within which it occurs. Bad work is myopic. Furthermore, it is important to point out that bad work is not merely the kind of mindless work described in The Jungle. Richard Weaver notes that thousands of highly trained specialists worked for years on the Manhattan Project. The secret nature of the project precluded most from having any clear knowledge of the end toward which they labored. According to Weaver, this ignorance, embraced quite willingly, reduced the participants to “ethical eunuchs.” Because they paid no attention to the purpose of their work beyond the narrow confines of their specialty, they forfeited the ability to judge the quality of their work, and an inability or an unwillingness to attend to the quality of one’s work will invariably lead to bad work.

Good work is intimately tied to stewardship, and this reminds us that in the Genesis account of creation, the first man and woman were placed in a garden and tasked with tending it. Their days were to be spent cultivating the creation. Paradise, it seems, was not a condition of idleness and ease but one of meaningful work interspersed with regular days of rest, of re-creation, of Sabbath.

This natural suitability to work is hardwired in all of us. I see it in myself and I see it in my children. Even if they groan when I tell them there is work to do, they derive a great deal of satisfaction and a sense of accomplishment when they look back at the pile of leaves they raked or the fence they painted. My thirteen-year-old son works each Saturday for a neighbor. He quite willingly gets up even on cold mornings to spend a few hours, usually in solitude, working on our neighbor’s property. The work is nothing special, raking leaves, trimming trees and the like, but the standard of excellence is clear, and he can take pride in doing good work. Having a job has, in fact, moved him well along the road to becoming a man.

Those of us who spend most of our days working with ideas that all too often thin into mere abstractions are, I think, in danger of forgetting the full goodness of work even as we struggle to accomplish all that we have to do. Checking items off a to-do list is not the same as laying the foundation of a house. Writing a paper or delivering a lecture can, of course, be satisfying, but there is a unique concreteness, perhaps a less obscure goodness, in building something that occupies space and is useful or beautiful.

Recently I tiled the floors of our bathrooms. My son helped me lay the tile and grout the seams. Together we covered the stark nakedness of the subfloor with carefully aligned tiles that transformed the work zone into a lovely room. There were clear and objective measures of quality that both of us easily recognized. When we finally stood back to admire our work, we knew we had done a good job, even though at the same time we knew where the little mistakes and misjudgments were located. No one needed to validate the goodness of our work, for the standard of excellence was obvious to all.

Work in the world of ideas is rarely as easily evaluated. When a person writes an article, he must send it out and wait for the opinion of other readers to validate (or invalidate) the quality of the work. And even then, often the evaluations are mixed and the question of quality is left suspended, sometimes indefinitely. The heft of a hammer in the hand, the jolt of a shovel striving against rocky soil, the ache in the back at the end of a day in the garden, these provide a connection to the world and a satisfaction in work that is a needed complement to the vagaries and abstractions of the world of ideas. It might even be that the latter kind of work provides a necessary grounding for the former.

So on this day devoted to giving thanks, lift a glass or a turkey leg to good work. Give thanks to the cook who prepared the meal with skill and devotion to the art. Give thanks that our lives provide continuous opportunities to engage in the kind of work that is suited to our embodied condition and our creative natures. And let us joyfully give thanks to God from whom these blessings flow.

3 comments

Jim Aune

And how many libertarians have been involved in destroying the one American institution that protected the protected the dignity of labor, the unions?

abersouth

If only labor unions stopped there. Then you would have an argument. They don’t and so you don’t.

Lewis Grant

Hannah Arendt’s distinction between work and labor seems perpetually relevant. We seem to have lost any functional-teleological understanding of the place of work in a full human life. We now only see products which can be sold (and thus measured according to a non-teleological, value-free ‘science’ of economics). Even though the economic life necessarily involves production and use, we now act as though the production side doesn’t exist (and use turns into pure consumption, which leads to what she termed the ‘waste economy’). Our ‘science’ tells us to turn work into ever-finer divisions of labour, so that we can consume ever more products to numb the pain of our ever more soulless jobs.

The American economy is probably more geared to the interests of consumers (rather than workers) than most other industrialized western countries. Yet we probably have fewer days of rest (what we Puritans contemptuously deride as ‘vacation time’, John Locke’s implicit warning about ‘idle hands’ firmly in mind) than any other industrialized Western country. One wonders if the degradation of work has also resulted in the inability to properly engage in (or even conceive of) the Aristotelian sense of leisure.

Comments are closed.