I think it is unquestionable that of the two Homeric epics, it is the Iliad which is the finer work of artistry, a judgment shared by the author of On the Sublime, who likened the Odyssey to a setting sun, “whose grandeur remains without its intensity.” That said, it is probably the Odyssey which captures the ethical ideals of the ancient Greeks more unambiguously, particularly in the way it emphasizes the necessarily communal basis of any such ideals. The work is essentially one long hymn to the centrality of home, understood as both place – “Ithaca, crown of islands” – and, more significantly, the network of one’s relationships of mutual dependency, the sphere of one’s duties, and therefore the foundation of one’s moral identity. One cannot begin to enter into the imaginative world of the Odyssey until one grasps the extent to which love of home motivates Odysseus and his son Telemachus; none of their major actions in the story is the least bit intelligible except in the light of such motivation. It is of the first importance to the proper interpretation of the epic, that when we read of the flight from Ogygia, or the journey to the underworld, or the passage by Scylla and Charybdis, we are witnessing the adventures of a man intent on reaching home, who willingly encounters those perils precisely because they are unavoidable trials on the path to his home.

When we first encounter Odysseus in the story, we find him peering longingly across the sea, weeping with nostalgia for the kingdom from which he has been absent some twenty years. He is detained in Ogygia against his will, by the beautiful and ageless goddess Calypso. Homer represents her island domain as a kind of demi-paradise, adorned with every natural luxury the mind could conjure (including the relentless erotic attentions of the goddess herself), and so astonishing in its outward beauty that the messenger god Hermes, alighting there to deliver an order of Zeus, is dumbstruck in wonder, though he himself resides in the precincts of immortal Olympus. This depiction of unlimited natural abundance is presented to us in direct contrast to an earlier description of the island of Ithaca, for when Menelaus offers Telemachus a gift of horses to take with him upon his departure from Sparta, the young prince replies that there is no room for horses to graze in his homeland, on account of its rocky barrenness. Yet it is to this place – which is, objectively speaking, vastly inferior to the place of his present dwelling – that Odysseus desires, with all his heart, to return.

That return is – as Odysseus knows it must be – fraught with every sort of suffering and misery which can afflict a man. The catastrophic condition of the hero is best illustrated by the fact that he is repeatedly required to declare himself a suppliant – to the Cyclops Polyphemus, to the river-god on the coast of Phaeacia, and to King Alcinuous and Queen Arete. To be a suppliant means to reveal oneself as utterly without power, and it is the contrast between this helplessness and his former (and future) regal authority that impresses upon us, the readers, the depths of the man’s wretchedness. But the cause of that wretchedness is simply his absence from his home. There is no kingship without a kingdom; there is no identity outside of one’s communal relations. So when Odysseus tells Polyphemus that his name is Nobody, he is devising another masterful ruse, to be sure, but he is also attesting to the fact that, at this point in the story, exiled from the soil in which were planted the roots of his own self-understanding, he has become divorced from his true self, – in the words of Keats’ Saturn, he is “gone away from his own bosom.”

We can say with confidence, then, that for Homer and his Greek audience, Odysseus’ condition in the course of his journey home is represented as the most miserable state in which a man can find himself. The wanderer, the exile, the suppliant – these are the words one uses when one wishes to identify the very nadir of human fortunes. And it is precisely for this reason that a very fruitful contrast may be made between the great epic poem and that standard of the American tradition, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, because in this latter work, the very same state of wandering and homelessness is depicted, in rather unambiguous fashion, as the very height of human happiness, and the necessary precondition for moral flourishing.

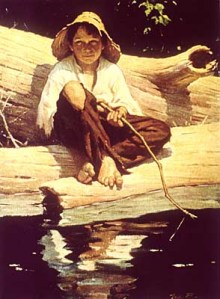

The river journey of Huck and Jim is, like the journey of Odysseus, beset with danger and hardship, but it is danger and hardship that is encountered in a flight away from home – away from Huck’s abusive father and from Jim’s enslavement. The novel ends with Huck stating his intention of “lighting out for the Territory” to avoid being civilized by Aunt Sally, so that even as the story concludes, he remains effectively without a home. The raft, which was for Odysseus the vehicle of his torment by the offended god Poseidon, becomes for Twain’s two heroes the scene of salvation, the means of liberation from their oppressive past: “We said there warn’t no home like a raft, after all. Other places do seem so cramped up and smothery, but a raft don’t. You feel mighty free and easy and comfortable on a raft.” It is when they leave their raft behind, and wander among the people who live along the Mississippi River, that their troubles begin, whether at the homestead of the Grangerfords, or the Phelps’ farm. According to Twain’s vision, it is the communal world of men that is the arena of agony, the secluded exile of the river-journey that is the scene of repose.

Most significantly, it is from the time which he shares alone with Jim that Huck comes to grasp the common humanity of this man, whom all the rest of the world perceives as mere property. None of the adults in Huck’s world – from his obscene father, to the conniving King and the Duke, to the apparently learned but truly obtuse doctor who treats the gun-shot wound of Tom Sawyer – can see beyond Jim’s race to recognize the person. Huck himself fails to do this consistently until near the book’s conclusion. But when he is finally able to gain this insight, it is as a direct consequence of attending to his own instinctive decency, and, most crucially, by divesting himself of the prejudices of the community in which he was raised. The prerequisite for Huck’s moral growth is a departure – intellectually, as well as physically – from his home, and everything that defines it.

So we can fairly say that the journey of Huck and Jim is a journey of liberation, but what they are liberating themselves from is their community. Their good fortune lies in the fact that they have successfully affected that severance by the story’s end. In the same way that the Odyssey effectively serves as a celebration of the well-ordered community, we can say that Twain’s novel serves as an encomium to the moral primacy of the individual. And of course, it is precisely because this uncompromisingly individualistic ethos lies at the heart of the book that it has attained its status as the great American story, as seminal to our culture and thought as the Odyssey was to the culture and thought of the ancient Greeks. But it is this very fact which should disturb us.

Consider Alasdair MacIntyre’s history of the Aristotlean-Thomistic tradition of moral inquiry. What MacIntyre emphasizes – first in After Virtue, and later, with greater elucidation, in Whose Justice? Which Rationality? – is the way the Homeric epics inaugurated this particular tradition, by bequeathing to subsequent thinkers a vocabulary and conceptual schemata of ethical and political thought. Foundational concepts like dikae and time are employed for the first time by Homer, and receive their significance from the way they shape the actions of his heroes. Later authors, as various as Thucydides and Aristotle, will reexamine and reinterpret these concepts in highly disparate ways, but their starting point will always be the work of Homer, and this indicates that his poetry served subsequent thinkers as, among other things, a guide to political reasoning, understood broadly as the art of constructing a well-ordered community.

But quite clearly, Twain’s novel could never serve us in the same manner. On whatever other grounds we may value his book, it should appear quite obvious that it bequeaths to us no such conceptual legacy, and possesses no such political relevance. It could never initiate any serious tradition of inquiry regarding the nature of justice or honor in a well-ordered community, because its underlying theme is a hostility to community as such, and a conviction in the intrinsically malign influence of man’s communal life. Political reasoning can begin from no such premises. So we must say that when we engage in serious political reasoning, we will have no cause to refer to Twain’s book. And what is true of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is equally true of Walden, of The Great Gatsby, and a host of other books which we are accustomed to regarding as classics of our national literature. The fact is that we Americans inherit a literary tradition which has very little wisdom to impart to us concerning the right ordering of our communities. What Homer was to the Greeks, what Dante was to the Italians, what Shakespeare was to the English – the well-spring of civilized values and the foundation of authentic moral inquiry – no author has ever been to us. And I think our politics has suffered as a consequence.

It is highly significant that our national literary hero is an untutored adolescent, who believes that an individual can flourish in the absence of a home and its significant relationships. We have, until this day, indulged in our individualistic reveries, imagining that we are always free to “light out for the Territory” and leave the ills of communal life behind us. What surprise can there be, then, that we have a political discourse which is often misguided and ineffectual? What we need is a new national story, one that captures in a manner unique to our history and location, the abiding truth that what is most desirable to human creatures is a home, and that all of our journeys remain incomplete until they have led us to this destination.

14 comments

Jack Stewart

Excellent and profound essay. Thank you!

I would be interested in what you think of the trajectory and especially the ending of Cormac McCarthy’s “border trilogy” in light of your critique of the major texts of American literature.

sancrucensis

A very brilliant and thought-provoking essay. MacIntyre argues that part of what enables the Odyssey to be a “national” epic is that it is about Greece’s heroic age. That is, it provided the Greeks with their historical memory of an age in which their moral concepts had their origin, but which had a much simpler relation to those concepts. The simplicity consisted in the fact that “morality and social structures are in fact one and the same in heroic society.” That simplicity holds for both Greek and Germanic heroic society, but it does not hold for the American equivalent, because (as you point out) the American “heroic age” is all about “lighting out for the Territory and leaving the ills of communal life behind us.” I guess that’s why none of the authors that people have mentioned have been able to write a truly national story. Pace to Kate Dalton, but I think that this is not simply because “boomer” authors are more lauded by the press than “sticker” authors, but because even the American stickers have a certain anti-political element. The “sticker” who came closest to writing a national story (as far as I can see) was Laura Ingalls Wilder, but I think that is in fact partly due to her strong anti-political streak: “Pa said there were too many people in the Big Woods now … He liked a country where the wild animals lived without being afraid.”

The authors who have tried to provide America with a more home-centered national story, end up writing protests. Look at FPR’s very own Booth Tarkington. His first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, is his most ambitious; it is really an attempt at writing a national story, and it’s all about Harkless learning the importance of home in every sense. But of course, it doesn’t quite succeed in its ambitions. His later novels (The Turmoil, Magnificent Ambersons, Alice Adams) lack the heroic element of Gentleman from Indiana, and rather than celebrating rural Indiana, they mainly protest against its industrial transformation. A protest is can never become a national story. I think it is highly significant that the most lauded novel of this year, Jonathan Franzen’s, Freedom is largely a protest, and has an entirely negative view of America’s heroic age:

Once [Einar, the father of Freedom’s protagonist] was [in America], he never went back to Sweden, never saw his mother again, proudly avowed that he’d forgotten every word of his mother tongue, and delivered, at the slightest provocation, lengthy diatribes against "the stupidest, smuggest, narrow-mindedest country on earth." He was another data point in the American experiment of self-government, an experiment skewed from the outset, because it wasn’t the people with social genes who fled the crowded Old World for the new continent; it was the people who didn’t get along well with others.

Mark Christian

I’ve promised to read the Odyssey along with my eldest daughter this spring; your reflections will further inspire this blessed endeavor.

As a Southerner, I’m bewildered by one of your last points, since many of us perceive within the tradition at least from Faulkner through O’Connor and Percy on to Berry a profound reservoir of wisdom regarding the well-ordered life (even as they depict the religious and cultural disorder of our times).

Would you consider them too “regional” to qualify as national literature? Or insufficient in some other way?

Nonetheless, many thanks for this contribution.

Mark A. Signorelli

Mark –

A couple of people have made a similar point. I certainly don’t want to claim that the entire tradition of American literature is bereft of stories centered in one way or another on the importance of well-ordered communities. The authors you mentioned here may in fact provide the sort of wisdom you say they do (though I find the inclusion of Faulkner problematic, on account of his modernist style – but that’s another article). But I wouldn’t say any of them have left us works of the sort that Homer or Dante have left us. More importantly, I don’t think any of their stories qualify as a kind of “national” narrative in the way that the Odyssey or Huck Finn do. I think its fair to say that among the works that occupy that kind of central place in our tradition, most (or at least, many) of them constitute some form of celebration of the individualist ethos (think about Leaves of Grass, supposedly the great American poem). And the point I was trying to make was as much about us, the American people, as about our literature – namely, the fact that we exalt these works (above, say, the work of an O’Connor) reflects how wedded we are to our atomistic conceptions of human life. That is not, to my mind, an altogether happy reflection.

By the way, I think your daughter will love the Odyssey. Year in and year out, it tends to be the book most enjoyed by my students, who, in general, are not book-lovers (to put the point mildly). Happy reading!

Mark Christian

I think Faulkner delighted in being problematic; that’s part of his enduring (and dismal) charm. Some of us read him as an elegantly grim pathology detailing much of what ails us. Hence, late-night forays into the Snopes trilogy require the consumption of Bourbon in generous quantities. Incidentally, I’m fairly certain that I descend from the underachieving branch of the Snopes family tree.

Walker Percy’s response to Faulkner, specifically The Sound and the Fury, continues to delight: “I like to think of beginning where Faulkner left off, with a Quentin Compson who DIDN’T commit suicide. Suicide is easy. Keeping Quentin Compson alive is what I am interested in doing.”

Regarding the question of a national epic or literary hero, I’m one of those localist pessimists who believes that America is (has become?) too expansive and diverse to warrant meaningful speech in the first-person plural – that the prevailing multi-cultural incoherence has rendered “us” numb to such luxuries. I wonder if “we” have become strangers to grand narratives like epics, in the way that Richard Weaver observed a contemporary discomfort with the spaciousness of the old rhetoric.

But here’s an oddball suggestion, inspired by a chapter in Pat Conroy’s recent memoir My Reading Life. For certain folks hereabouts, Scarlett O’Hara, the heroine of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, may be a startlingly more appropriate choice than Huck Finn. I’m well aware of the novel’s literary and cultural limitations (which may, in some backhanded way, account for its continuing mass appeal). But while Scarlett is deeply flawed, self-centered, and even Machiavellian, her tenacious devotion to cultivating life in a particular place (even a ruined place) is profound.

Something I ponder while rocking on my porch and listening to the mournful sounds of Iris Dement.

Now, on to Homer!

Devin

Mr. Signorelli,

Could you please expand upon why you believe that it is the purpose of literature to provide us with a conceptual legacy or political relevance, as you refer to it? It is not obvious to me that this is or should be the purpose of literature. I realize that this may be broaching a much larger topic that is beyond the scope of this forum, but would appreciate it if you could briefly indulge me.

Devin

Mr. Signorelli,

Could you please expand upon why you believe that it is the purpose of literature to provide us with a conceptual legacy or political relevance, as you refer to it? It is not obvious to me that this is or should be the purpose of literature. I realize that this may be broaching a much larger topic that is beyond the scope of this forum, but would appreciate it if you could briefly indulge me.

Mark A. Signorelli

Devin-

That is a very important question (and certainly goes to one of the more disputable claims in my essay). Like you said, I’m not sure I can do justice to that topic here, but let me just throw out a couple of cursory thoughts.

I would start with Dante’s claim that poetry is the truth spoken beautifully (or something like that – I don’t remember the quote exactly). So if the poet (or novelist or short story writer) is doing what he ought to be doing, he is (among other things) describing the world in a truthful fashion. To reflect on that description is necessarily to take up the language of the poet to some extent, and this is all I mean by a conceptual legacy. What MacIntyre is really saying (and I don’t think I made this clear enough) is just that Homer enunciated some profoundly important truths about our moral lives, which subsequent thinkers took as the starting point for their reflections. I certainly don’t want to say that any poet or fiction author should intend to leave a conceptual legacy behind, or to affect politics – that this should be a “purpose of literature” in that sense (so maybe we agree here). I simply believe that, insofar as a writer has delineated an accurate and compendious vision of the human world, his work is bound to leave that sort of legacy behind.

Why do I deny that Huck Finn has left that sort of legacy? Well, simply put, because I don’t think its very true. I don’t think the story Twain is telling is universally or fundamentally true, in the way that Homer’s story is. I don’t think that the corrupting tendencies of society (undeniable as they are) are the most significant facts about human society. And I don’t think a story about a boy’s defiance of his community represents the most important facts about the relationship between a young person’s moral development and their community. So I don’t think moral and political reflection gets a head-start from Twain’s book anything like it gets from a reading of the Odyssey.

That’s the best I can do in this short space (and with one eye on dinner on the stove), but I hope it helps a bit. Thank you for taking the time to think about my work so seriously; that’s always very gratifying to an author.

Kate Dalton

Thank you for a very good essay. I think you are right about both works, and about the larger conclusion. People living amid a healthy culture don’t want to leave it, and thus we Americans aren’t nearly as civilized as we think we are; certainly there is very little comparison to Greece. As sea-faring and colonizing as that ancient wandering people were, they were wise enough to understand that sometimes death was preferable to ostracism. Imagine any American of any era saying that.

That said, there are many excellent rooted books by American authors, and while none of them can touch the Odyssey, many are better than Twain–but our press has always been on the side of the boomers rather than the stickers. We do have a well to draw from, though, if we can simply remember and read the stories of home we already have. I’d start with The Memory of Old Jack and Country of the Pointed Firs myself (both perfectly comprehensible to the less screen-addled high schooler, too).

Candy Highlander

for hero’s journey, see Kal Bashir’s 510+ stage version at http://www.clickok.co.uk/index4.html

Empedocles

It is funny that so many great American books celebrate lighting out for the literal or figurative territories. American movies do too with George Bailey desperately trying to get out of Bedford Falls, or Luke Skywalker looking out at the horizon. But television, that medium most hated by Porchers has a history of celebrating family and community. Just think of any family sitcom’s view of the family as the most important thing, or shows like Northern Exposure, The Simpsons, or of course, Andy Griffith, that celebrate place and community.

Patrick J. Deneen

Mr. Signorelli,

Thanks for this fine exegesis – I agree in considerable part. However, I’m willing to give Huck a bit more credit – after all, he makes (at least what he thinks to be) a great sacrifice for his friend (i.e., his belief that in helping Jim to escape slavery, he will go to Hell), showing that he’s not quite the individualist that one might suspect. And, perhaps he does find his way back home – perhaps we find him in mid-story, just as we might make the same conclusion about Odysseus were we to draw conclusions based on his willingness to tarry with Circe (only departing when beseeched by his men). And, if Dante is to be believed (as well as hints in the “Odyssey” itself), it’s not clear that Odysseus is quite the homebody that we might conclude. The temptations (and rewards) of departure, and the rewards (and hazards) of homecoming, are deeply laced in western literature, and perhaps what could be concluded is that it’s an eternal contest in our own American (and Western) soul. It’s one that’s played out, among other places, in that now-classic American film “The Wizard of Oz….” (Dorothy returns to Kansas, but in a later novel, returns to Oz with her family to live).

I’ve paddled in these waters as well – anyone interested in reading my own musings on the relationship of the “Odyssey” and “Huckleberry Finn” are most welcome. This little study includes a bit of literary detective work – an unpublished book review by Twain of a German translation of “The Odyssey,” written around the time that Twain was finishing work on “Huckleberry Finn.”

http://patrickdeneen.blogspot.com/2008/11/happy-birthday-sam.html

Mark A. Signorelli

Prof. Deneen-

Thank you for the kind words. I did in fact forget about Dante’s version of Odysseus’ story (all the more unforgivable, since Tennyson’s Ulysses, based on that version, is one of my favorite lyric poems). And yes, Odysseus’ relationship to home is perhaps a bit more complicated than I have let on here. One of the most awkward moments in class every year is when, having gone on and on about Odysseus’ desire to return home to his beloved Penelope, I read with the class the scene in which he beds the beautiful Calypso (pining for home the entire time, of course). It takes quite a bit of verbal ingenuity to work myself out of that spot.

I have to admit that I have always been unsatisfied with that scene in which Huck tears up the letter and declares “alright, I’ll go to hell.” It seems like the moment in the story that should constitute the Aristotlean anagnorisis, the moment of recognition, but there is in fact no “change from ignorance to knowledge.” Huck, in deciding to free Jim, doesn’t really think he’s doing the right thing. Its never clear (at least, to me) that he understands that his society has been perpetrating a grotesque injustice, in the form of slavery, and that a defiance of that institution would constitute a commendable act. For this reason, I find it hard to understand his action here as one of selfless sacrifice. It appears to me (and it certainly appears to Huck) to be just one more example of his adolescent defiance of society, in line with the pranks that he and Tom Sawyer were pulling off in the novel’s opening chapters. And this is why I have always understood the book less as a critique of certain nefarious prejudices of Twain’s time and place, than a kind of general celebration of antisocial defiance. But then, my distaste for Twain’s style may simply make me too unsympathetic a reader to interpret his story properly.

Comments are closed.