Rock Island, IL Allen Tate said something somewhere about “the insuperable frustration of learning to write.” That Tate said this is good news for the rest of us, for of the writers “who came to maturity in the late 1920s,” as R.K. Meiners said in The Last Alternatives, “Tate is one of the three or four most important.” If someone as formidable as Tate found learning to write difficult and frustrating, perhaps we minor leaguers can make temporary—or maybe even lasting—peace with our own frustrations.

The great Michigander, Robert Traver, who wrote easygoing iridescent sentences when he wasn’t sipping a drink and listening to Delius, suffered a different kind of frustration: one was that as a lawyer he had to work, and work only got in the way of catching trout and writing novels. Another was that, as a judge, he sometimes had to read legal opinions, and most legal opinions, he said, are written by judges who “write with their feet.” (He ought to have read literary theory in the 1970s and 1980s, or the plodding textbooks written by composition theorists, most of whom should have written with their feet.) So when he was called upon to write legal opinions, as he sometimes was, Traver was mindful of the golden rule. But then Traver was a good man: like all good men he believed that, for the sake of others, he ought not to be dull.

I would that more writers were of this belief. Too many are frustrated by, and too few are frustrated with, their own dullness. Put another way, they’re boring and don’t know it.

Now there are frustrations of the sort Tate had in mind, and any serious writer engages them in dubious battle, for they are serious frustrations. But what of dullness? What of writing with your feet? What, indeed, of those who write with their feet but think they write with their hands, or those who write with their hands but never think to write with their ears? And what of those who have never once thought it their duty to amuse their readers?

I remember reading William Zinsser’s On Writing Well when I was pretty young and being struck by his advice to indulge in a joke if the moment seems to call for it. You can always take the joke out later, he said, but only you can put it in. Another thing he said: if you leave the dullards in the dust, well, that’s where they belong.

That’s what I would call two good pieces of advice.

Not every writer is going to risk the joke, or the allusion, or the newly-minted word, or the slight twist of expression (as when in that great poem, “Fern Hill,” Dylan Thomas wrote “once below a time”), just as many writers will not be happy until all the dullards have picked themselves up, dusted themselves off, and joined all the interesting people at the pub (who are none too happy about having them there).

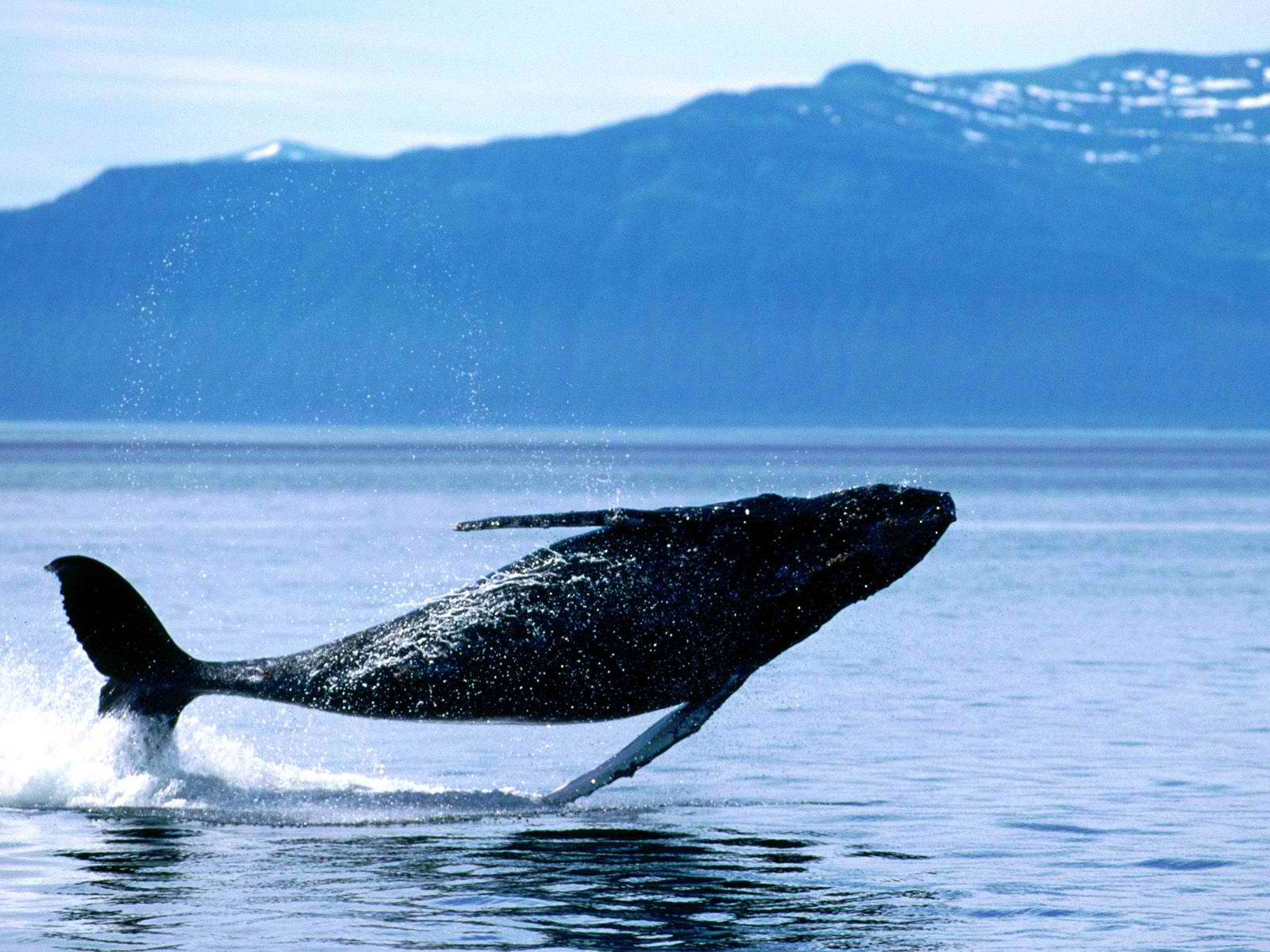

But is it asking too much that the writer regard language as, say, leviathan regards the water: as the place wherein he takes his pastime? Is it too much to ask that a writer learn to imitate a whale and frolic a little?

One of the benefits of being a whale is that you know how to play. One of the benefits of studying baroque poetry, unless all you care about is “reification” or “subverting the dominant discourse,” is that you learn something about art as play. You learn something about how the poet (or musician or sculptor) stands in relation to the supreme Artist, whose own work, like leviathan’s, is an unceasing act of exuberance and joy. This is an Artist who will risk a joke or a twist, an artist who knows that only he can put the joke or the twist in. This is an Artist who has a blow-hole and knows how to use it.

And apparently He can bear to leave the dullards in the dust, else why would He have given us the orangutan’s face and the monkey’s ass? The dullard doesn’t know that there are aspects of the creation he can laugh at. He thinks everything is like Corn Flakes, cold toast, and the stock market report over coffee.

Nor is the dullard capable of sport, much less disport. Tell him a joke, and his ashen expression tells you he never even tried to soak his pal’s fingers in warm water at a sleep-over. Wonder he is barely capable of. He is more like a camera than a man: he registers but does not see. This is why he is a dullard. And he is the only one who doesn’t know he’s a dullard. Make a writer of him and you’ve got an epidemic of narcolepsy on your hands.

Not so the baroque artist, and not so the Artist he imitates. The former says “I am a little world made cunningly”; the Other cunningly makes him a little world and takes odds with the angels on whether he or any of the others will figure it out. The artist sees in the Artist’s creative act a kind of license to make his art as cunning as he can make it and then freely goes about the business of being cunning; the Artist rejoices to hear him say “go and catch a falling star” or “we’re tapers too and at our own cost die” but doubts anyone will get what he’s saying. But He also knows that these others don’t really mind being left in the dust, that they can’t mind the dust, and He probably doesn’t mind that they don’t mind. There’s something about an inside joke. Take it outside, and it’s not an inside joke any more.

But if the baroque artist is exuberantly at play—at play like leviathan, like the Creator of both the baroque artist and leviathan—he knows to respect the formal limits of that play. He may be frustrated with his own limits as a poet, but he is never frustrated by the formal limits of his craft, for without them there would be no craft at all. Even the waters where leviathan takes his pastime respect their limits: the ocean, which we are justified in calling a kind of divine artistry, is limited: the waters go “even unto the place which thou hast appointed for them. Thou hast set them their bounds, which they shall not pass; neither turn again to cover the earth.” The divine artistry hangs upon a formal limit, just as a painting depends upon a border and a frame and just as, indeed, it hangs upon a wall. So the sonnet is limited by its syllabic count and other formal constraints. The poet wouldn’t have it any other way. Otherwise he’d be playing tennis with the net down, as Frost remarked. The true artist knows how to be at play in his fetters. He also willingly puts them on.

And Dylan Thomas sang in his chains like the sea.

There are frustrations that attend all things, for all things thrive within limits, and limits are frustrations. We are limited by our abilities, obviously, but also by the constraints of language itself and our poor uses of it, by our asking too much of it here, too little of it there. And we see in these limitations a likeness to the beasts as well as to the divine Artist, who has limited Himself by entering into an agreement with the order of things and with his own word.

But the order of things is a rule that exceptions must prove, which may be why the son of a certain Palestinian carpenter made a point of spitting in the clay and making mud on the Sabbath in particular. If so, I incline to say that the regions of greatest interest—of least dullness—are often the margins, the edges, the constraints, the limits, as if what we are most interested in, if we are interesting, is what we can get away with once we’ve given our fetters their proper due. What we do as writers and artists and men and women just before curfew is what really catches the eye—just as, say, a cotton shirt straining against its limits is what really fends off dullness.

And you can always leave the cotton shirt in the drawer, but only you can put it on.

7 comments

Austin Detwiler

Interesting. Thanks.

Matt

This is a wunderbar piece. Thanks for sharing!

Jason Peters

Mr. Detwiler: Writing in general. William Empson was the sort of critic who gave the words their freedom to sport a bit, as is Eagleton today, while never sacrificing clarity. You will still encounter your Polonius, who is for a jig, or a tale of bawdry, or he sleeps. But Hamlet knew what to do with such a dullard.

Austin Detwiler

I prefer to leave my shirt in the drawer.

Quick question:

You say that a writer should ‘frolic a little.’ Is this a suggestion for novels and blogs, or writing in general? Ought a writer of academic literature (or legal reports) add a joke, or ought he be concise and clear (note that I’m not suggesting ‘he write with his feet’ and forget his ear)?

Thanks.

dave

Well, that’s a keeper, Professor. Thanks. Now, a confession: I’ve been contemplating my retort and instead – I suppose some unwelcome late night glance into a mirror – realized I’m simply the incarnation of a disagreeable fellow. “Yes, but” too often comes to mind. Of course, then follows the secondary realization that I must be quite difficult to live with, and what relief it must be for my wife these days that we have the internet, since the opportunities I now possess to vent spleen are incalculable and she must necessarily be spared my contrary nature if for no other reason than my own exhaustion. Therefore, being dutiful and not meaning it personally: have at you.

Sam M

“And what of those who have never once thought it their duty to amuse their readers?”

I thought that’s what movies were for.

Zac

My fetters are like sweaters: exceedingly dull.

Comments are closed.