I am a middle-aged professor of political philosophy with a decidedly traditionalist scholarly disposition, and I have a confession to make. I am convinced that the music of Bruce Springsteen represents a serious artistic achievement. I have not always held this conviction, mind you. Back in high school and college I thought Springsteen was fabulous, especially in live performance. But rock and roll is supposed to be one of those adolescent things that you leave behind when you become a man, and especially so when you are set to study classical political thought at the national university of the Roman Catholic church in the United States. So by the mid 1980s, rock music and all that it represented had been shown the door.

This all changed early last year. At that time I found myself having to make, for family reasons, about a half-dozen 1500 mile road trips up and down the front range of the Rockies. On one of these lonely drives I switched from audio books to satellite radio, and fell upon a station called “E Street Radio”: all Bruce Springsteen, all the time. The station brought back some nice memories, and it introduced me to a lot of music that I had missed over the years. They say long periods of isolation can do strange things to a man, even to the point of making him enjoy the creative output of a socialist songwriter.

But I continued to listen during more sane times later that summer, and to my surprise I found a large quantity of music that ought to be of interest to thoughtful people concerned with questions of limits, scale, and personal character (such as FPR readers). And most surprisingly, I thought it might even be of interest to conservatives. I began to sense that maybe Springsteen’s political reputation was not entirely deserved, or at least required some qualification. By the time his The Promise album and documentary were released in November, I was sure of it. One interview on the occasion of the documentary’s release confirmed what I had heard in the music over the previous six months, and convinced me that this was no ordinary rock musician:

….the good part about [Asbury Park, NJ] was you were very, very connected to place. And it was unique, the place where you lived and you grew up, and the people you grew up with were very singular…My desire [was] to…not get disconnected…[Music] was a way of honoring my parents’ experience and their history…a lot of the people I cared about, I said ‘well these things…they aren’t really being written about that much’… And those were the topics I decided to take on, not so much out of any social consciousness, but as a way of survival of my own inner life and soul…I was interested in a sense of place…I felt that my own identity was rooted in that sense of place and that there was a narrative there. And I was interested in having a narrative. In other words, I had a story and I wanted to tell it.

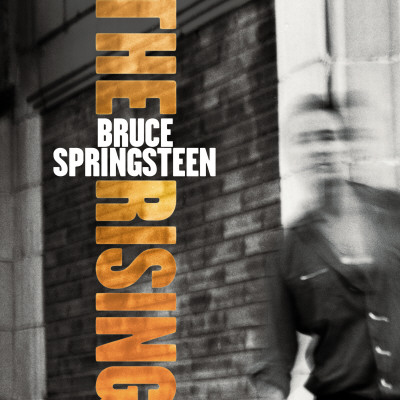

Since then I have been quite deep in the music, and in June started doing research and writing in earnest. The project has taken me recently to the 2002 album The Rising. The timing here was too interesting to pass up, because the songs on this record were written in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. I had to get something out, and FPR was the obvious place.

Legend has it that a stranger on a New Jersey street, shortly after the attack on the World Trade Center, shouted into Springsteen’s open car window: “we need you now.” No one who has followed Springsteen’s career over the years could have been surprised by the remark, or by Springsteen’s decision afterwards to record a new album. During times of crisis, we would expect an artist to attend to what matters most in life, and The Rising delivered. It was bound to be his best production since the mid 1980s, for the events which inspired it could not have been more firmly in his songwriting wheelhouse.

A principle theme in his music has always been the dissolution of community under the impact of industrialism and consumerism, and the effect of this dissolution upon individual lives. Nothing threatens local communities quite like a war. Moreover, a considerable number of Springsteen’s songs old and new are marked by their dark story lines and settings, complete with ruminative, tormented characters who, in various states of psychological confusion, agonize over matters of personal identity and existential redemption. They do so because of their alienation from people and place. There is nothing like a disastrous terrorist attack to bring out the best in a songwriter who embodies the urban/suburban gothic styles in American popular music, but one who also refuses nihilist despair. He believes that anguish can turn to hope in the presence of vibrant community life.

The Rising, like many of Springsteen’s albums, is an extended meditation on the kind of demands placed upon people as they face the tragic circumstances of their lives. The tragedy here is explicitly September 11, the “Lonesome Day” from the opening song on the album: “Hell’s brewin’ dark sun’s on the rise…House is on fire, Viper’s in the grass.” The musical response to this tragedy is surprisingly nonpolitical, especially given Springsteen’s reputation in recent years for left-wing activism. While I cannot speak for his personal views, whatever they are, it is clear that the music on this album seems far more interested in what is happening to concrete individual human beings than in any specific ideological program or explanation.

Most illustrative is the song “You’re Missing,” in which we hear the heart-wrenching story of a surviving wife faced with the necessity of telling her children that their father is dead. There is no political statement attached, there is only the artistic expression of the encounter between human beings and the real force of evil in the world. Springsteen has no interest in abstract, hubristic ruminations about evil; he provides straightforward accounts of flesh and blood reactions to it. And these reactions always occur in a specific, concrete setting – in this case, the household as the most intimate of places. His descriptions are often peppered with textured mundane detail, as though to emphasize the importance of that place:

Pictures on the nightstand, TV’s on in the den

Your house is waiting, your house is waiting

For you to walk in, for you to walk in

But you’re missing, you’re missing

You’re missing when I shut out the lights

You’re missing when I close my eyes

You’re missing when I see the sun rise

Springsteen’s craft as an artist is centered on illuminating the core experiences of our humanity in the midst of extreme suffering. It is in this way that the influence of Flannery O’Connor can still be felt in Springsteen’s music, almost thirty years after his noir classic Nebraska (1982). At that time he identified O’Connor as part of “the really important reading” that he began during the late 1970s. In explaining the stark brutality and violence of her own fiction, O’Connor once said that “redemption is meaningless unless there a cause for it in the life we live.” Springsteen’s music is in complete agreement, and this is as evident on The Rising as it is on Nebraska. “There was something in those stories of hers,” he said,

that I felt captured a certain part of the American character that I was interested in writing about. They were a big, big revelation. She got to the heart of some part of meanness that she never spelled out, because if she spelled it out you wouldn’t be getting it. It was always at the core of every one of her stories – the way that she’d left that hole there, that hole that’s inside of everybody. There was some dark thing-a component of spirituality – that I sensed in her stories, and that set me off exploring characters of my own. She knew original sin – knew how to give it the flesh of a story.

It turns out, however, that Springsteen’s gothic can’t resist making an attempt to fill that hole, or to point us in the right direction at least so we can fill it ourselves. In this respect he is willing to gives us a bit more help than O’Connor is. In The Rising we run into characters that, in response to disastrous circumstances quite beyond their control, come out with a resolute determination to regain themselves somehow. They carry with them an abiding faith that redemption, a “rising,” is there for those willing to search for it. (They never come out of their suffering with political demands or grand programs of action).

The singer of “Lonesome Day” maintains his faith that “this storm’ll blow through by and by…this too shall pass, I’m gonna pray.” The chorus reminds us: “it’s alright, it’s alright, it’s alright.” There is a way out of the nihilistic depths revealed by the suicide bombers; the spiritually mature encounter the nihilism and pull back in the direction of life. The sudden appearance of evil forces us to reflect anew on how we relate to others, especially those closest to us: “Once I thought I knew/Everything I needed to know about you/But I didn’t really know that much.” It is only through the encounter with evil and death that a knowledge of what is most important is thrust upon us.

The same idea with richer lyrical content is found in “Into the Fire,” a song about the heroes of September 11 who gave their lives for others. Most importantly, the song is about an experience of the living: that from such sacrificial loss can emerge hope and meaning.

You gave your love to see in fields of red and autumn brown

You gave your love to me and lay your young body down

Up the stairs, into the fire

Up the stairs, into the fire

I need you near but love and duty called you someplace higher

Somewhere up the stairs into the fire

Chorus:

May your strength give us strength

May your faith give us faith

May your hope give us hope

May your love give us love

The chorus is the antiphon of this prayer-like song; it is repeated eight times. Like a liturgical antiphon, it gives the key to the meaning of the catalytic historical events of the Lonesome Day. This meaning centers on matters of personal virtue (especially self-sacrifice, courage, and honor) and the bond of community created by the exercise of these virtues. It has next to nothing to do with politics ordinarily understood.

The title track draws on the same theme. “The Rising” is a powerful song that is not about rising up for revenge, or any such political notion. It is rather an honorary tribute to the virtuous, a requiem for those who gave their lives for others on September 11. It is also a call to virtue directed at the listener. We the living are exhorted by the lost heroes to “rise up” to the possibility of our own redemption in the face of evil. Like “Into the Fire,” the song draws on religious imagery as the fallen send forth their call from the next life:

I see you Mary in the garden

In the garden of a thousand sighs

There’s holy pictures of our children

Dancin’ in a sky filled with light

May I feel your arms around me

May I feel your blood mix with mine

A dream of life comes to me…

Sky of blackness and sorrow (a dream of life)

Sky of love, sky of tears (a dream of life)

Sky of glory and sadness (a dream of life)

Sky of mercy, sky of fear (a dream of life)

Sky of memory and shadow (a dream of life)

Your burnin’ wind fills my arms tonight

Sky of longing and emptiness (a dream of life)

Sky of fullness, sky of blessed life (a dream of life)

Springsteen’s musical heroes are not political actors, and they are not warriors. They are those who “act locally,” those who do their duty to those closest to them and find deliverance in the process. Remarkably, the Springsteen of The Rising takes no interest in academic “root causes,” or demands for this or that political action. Rather, he takes a very measured response that is centered on the exercise of virtue on the part of individuals, and little more.

Tied to this response is his recognition that our individual quest for meaning in the midst of chaos is not done in a social vacuum. It is inextricably bound up with the order of the local places we inhabit. The virtues are practically meaningless in the absence of a community, even if it is constituted by just one other person. The virtues are most immediately and concretely exercised in the intimacy of family, and extend ultimately to other small-scale group associations (friends, neighbors, town, and state – never to nation or empire). Springsteen knows that these associations are the arena in which the most meaningful human experiences are always played out.

“Lonesome Day,” for instance, opens with the singer professing, in the wake of the chaos and uncertainty, a renewed interest in the most elementary form of community: husband and wife. in the life of an individual: a spouse or lover. The importance of family is unmistakable in most of the songs on this album. “Your Missing” is a meaningless song without the intimacy of husband, wife, and children; “The Fuse” contains a marriage proposal during a funeral procession in a small town; and “Empty Sky” and “Paradise” are mournful laments over the deaths of loved ones.

Many of these songs take us down dark and serious paths, but often turn around and remind us that sometimes the best response to the evil of this world is to create and maintain close ties with other people. The result, to our relief on this otherwise somber and reflective album, is sometimes joyous. The best example is “Mary’s Place.” This song is a rousing invitation to join a local gathering of friends and neighbors one evening. It is triumphant and celebratory in its musical mood. The narrative, however, is born of tragedy (Springsteen always has trouble letting go of his gothic sensibilities). One reviewer likened the song to an Irish wake. While in a festive frame of mind, the singer remembers with joy and fondness his beloved, a victim of September 11:

I got a picture of you in my locket

I keep it close to my heart

A light shining in my breast

Leading me through the dark

Seven days, seven candles

In my window light your way

The chorus’s accompanying refrain can indeed be “Let it Rain,” because the evil and suffering of that lonesome day have been met with the redemptive possibility of love. That possibility is expanded here to include friends and neighbors in a specific and meaningful place, Mary’s Place. That place, properly ordered in virtue, is capable of making the loss of a husband, wife, or child bearable. The song is full of religious imagery that is centered on the possibility of redemption through community:

My heart’s dark but it’s risin’

I’m pullin’ all the faith I can see

From that black hole on the horizon

I hear your voice calling me

Familiar faces around me

Laughter fills the air

Your loving grace surrounds me

Everybody’s here

Furniture’s out on the front porch

Music’s up loud

I dream of you in my arms

After this verse there is a line that is inserted in the middle of the next chorus. Springsteen has the line follow a familiar refrain, and occupy half the number of beats per measure as the chorus. The result is that our attention is forced on a line which is emblematic of the entire album: “Tell me how do you live broken-hearted?” The answer to this question turns into the accompanying refrain for the last chorus, and is also emblematic if taken with its full range of symbolic meaning: “Meet me at Mary’s Place.” Springsteen’s music does indeed return to the things that are most important in an hour of crisis. But contrary to popular impressions, these things turn out to have very little to do with politics. They have everything to do with the humane values of tradition: love of family, friends, neighbors, and place.

—

Gregory Butler is Associate Professor of Government at New Mexico State University.

19 comments

Steve G.

I see Bruce’s songwriting from a very different viewpoint than many in this thread, not focusing on whether he is authentic or not as a working class hero. He grew up with the struggles of the working class enough to tell a story of his dad trying to get the old car to start so he could get to work (intro to Factory on an old live triple album). He could express the exhilaration of getting a contract and a big advance in Rosalita. On Lucky Town’s song Local Hero, he pointed out the distance between his success and the persona in his songwriting. Bruce claims to understand the people in his stories, but not to literally be them. These people deserve being heard in his songs anyway.

I was attracted to Bruce, before Born To Run, for his ability to express the emotions which I felt. This is what has made The Rising and Magic two of my favorite recent albums. Even losses and frustrations that are personal are expressed in emotions that are more widely shared. Focusing on this is a path to connection and thus to healing.

Carl Eric Scott

Hey Porch rockers, I’ve got a post on another 9-11 album, David Bowie’s Heathen, over at Postmodern Conservative: http://www.firstthings.com/blogs/postmodernconservative/2011/09/22/carls-rock-songbook-21-david-bowie-sunday/

I’m not enough of a Boss fan to either defend or endorse the no-holds-barred critiques here, but Sam M. says some interesting things, and Hass is right about that MANSION ON THE HILL book

SCZ

Brilliant. He also said, “The subtext of all rock and roll is, ‘Take your pants off.’ Then, when you get married it’s, ‘Take your pants off, please.'”

John Haas

The epic take-down mentioned above might be an article in Vanity Fair maybe 15 years ago.

Also good on Bruce is the book MANSION ON THE HILL.

D.W. Sabin

Oh, , now I understand what Sonny Barger was doing to the Doc when he and the boys were swabbing the decks with him, making him an “authentic Hells Angel member”.

As Yoda pronounced , “moichendising” is the secret of the universe

Clown George

http://www.theonion.com/articles/bruce-springsteen-releases-new-scifi-concept-album,21358/

Had to post …

Sam M

I can think of a few people who did it their way. GG Allin, probably. GWAR. Fugazi. Which is fine if you believe it. Good for Bruce if he lives up to his press. He did it his way. Even if he didn’t, the idea that he did works as salve for people who want to think people can do it their way. Which is why I love my blue-collar Pittsburgh Steelers. Seriously, I do. But in those reflective, nagging moments when I investigate my own biases, I have my doubts.

As for “what the corporate guy wanted,” there is a very long history of corporate guys developing and packaging products that allow consumers to believe they are sticking it to The Man. This is why we have NASCAR, John Cougar Melencamp, Gangsta rap, CMT, Green Day and Fox News, all of which are fine products in and of themselves. I am just not sure why The Man would pay for these things if he didn’t see any value in it for himself.

Do you really think that Asbury Park “stuck it to the man?” Who would The Man, meaning the corporate music establishment, have been at the time? I would say.. Rolling Stone. In which Lester bangs gave the album this sloppy kiss:

“Springsteen is a bold new talent with more than a mouthful to say, and one look at the pic on the back will tell you he’s got the glam to go places in this Gollywoodlawn world to boot.”

How about that pic on the back? It’s almost like The Man was actively trying to market the guy. Which, again, is fine. You can market something authentic. But to argue that he has been fighting uphill against corporate resistance seems odd. He was signed with Columbia Records, if I recall. If they hated or feared him, they could have not signed him.

I go back to Tom Wolfe’s heroic piece about Junior Johnson in Esquire. All those NASCAR guys driving Chevy’s were sticking it to The Man, alright. Because Chevy was the car of choice for renegades. And The Man somehow ate it up, a couple thousand dollars at a time, while maverick man-sticker Junior Johnson flew from track to track in a private plane. Great. If you like the driving, you like the driving. If you like the music, you like the music. And if you like Bill O’Reilly, you like Bill O’Reilly. I am just not so sure that The Man is all that upset about all the sticking being done by these folks.

Gregory Butler

The idea that Springsteen is a “corporate construct” flies in the face of everything we know about him. His first album was entitled “Greetings from Asbury Park New Jersey” as a self-conscious attempt to stick it to the NY “man,” and there is not a song on it that would ever qualify for what the coporate guys wanted: 3 minute pop ditties to sell records. Before Born to Run, Springsteen was almost homeless. Mike Appel was convinced that the title track on that one was way too long for AOR airplay, but Bruce said stick it, we are releasing the single anyway. And what about “Nebraska”? It drove the Columbia Records people crazy. Springsteen always did it his way.

Gregory Butler

@Sam M. I find the “persona” argument unconvincing. You will notice the author of the slate.com piece draws on no evidence but his own gut feeling to make the claim. One exception might be his reference to the overwrought Landau made-him-a-star stuff, but Dave Marsh’s books destroy that thesis. And the author of the slate essay is not the only one to make the attempt to bring Springsteen down with the same cynicism we apply to other celebrities. Based on my reading of the man’s life and career, I don’t believe that “he is like every other rock star.” In any case I don’t care as much about the persona as I do the music. All artists have a bizarre persona.

Sam M

Chris,

I understand your point. The art is the art. But in Springsteen’s case, biography matters not just to me, but to his most loyal fans. They care that he’s authentic. They cite it as a main reason for their fandom. I am not arguing that he’s a complete phony. But supporting him for his aw shucks, Joisey Boy persona is akin to buying all your organic vegetables at Wal-Mart. You are falling for someone’s marketing schtick.

It mattered to fans that the guy who wrote “A Million Little Pieces” was an authentic addict. It matters to fans that Hunter S. Thompson is an authentic Hell’s Angel. It matters to fans that 50 Cent got shot 9 times. It matters to fans that the Pittsburgh Steelers are a blue-collar football team. It especially matters to them when the authenticity is part of the sell, and they feel betrayed when they discover that the sell is a big corporate contstruct.

People just have a way of accepting it more easily when they like what’s being sold.

Chris S.

Sam M. — I’m not sure there is anything wrong with the persona being a persona, if the art is good. For whatever reason, Mr. Springsteen seems better able to explore humanity through rock/pop music than almost anyone. While I doubt some of the more epic take downs — simply because they are epic — if it were all an act, the music would still remain the same.

Dickens wrote for money and by the word. Its still really good.

Camille J.

Thanks for this reflection. I largely ignored Springsteen’s music for decades, until I stumbled across Robert Coles book ”Bruce Springsteen’s America: The People Listening, a Poet Singing.” I’m grateful to Dr. Coles for turning me on to a great story teller.

Sam M

I am surprised this analyss has not met with more resistance in these parts. Not because Springsteen’s music stinks, but because his persona is… pretty much a persona, like every other rock star. I remember an epic takedown a few years back, but I cannot find it. Here’s a shorter one, from someone who’s actually something of a fan:

http://www.slate.com/id/2117845/

Nothing wrong with a persona, but so much of his appeal seems to be based on his “authenticity” and his status as a regular guy from Jersey. Whether his music qualifies as “art” is another question entirely, but it all gets wrapped up in strange ways.

Gregory Butler

@Chris S.: you are certainly correct, there are a LOT of songs going back to at least Born to Run that express similar sentiments. It is too bad that space limits and the subject of 9-11 prevented me from fully developing this. I also love “Living Proof,” but I happen to like the rest of Lucky Town, too, and I know that puts me in a minority. Thanks for taking the time to read FPR,

GB

D.W. Sabin

Love, when it occurs, is a-political……Bruce loves his music and his audience . He is a better ambassador for Joisey than reality television or HBO likes to concoct. The man has a big bustin heart and this alone is enough for me.

Sometime during the last several decades, the “little guy” stopped being an American icon. Springsteen don’t buy it and we should thank him for his stories.

Chris S.

Thank you for this. I follow up only to note the sheer number of songs that you could have cited in support of your thesis that you didn’t even touch. To name a few:

The soldier afraid of losing his humanity in the midst of chaos in Devils & Dust.

The young, abandoned single mother in Spare Parts.

The unbelievably beautiful song of mourning for a lost city that cries out for its citizens to rebuild it in My City of Ruins (which was originally written for Absury Park but was transposed onto The Rising).

The hymns to seeking meaning in the face of everyday life, like Promised Land, Reason to Believe, and Racing in the Streets.

The small scale story of Mary’s walk with Christ in Jesus was an Only Son.

And we can’t forget the man who settles down in a small town, one night goes to the road (where he used to find freedom) and “didn’t find nothing but road” from Cautious Man.

And finally, I have to mention Living Proof; as a relatively new father, the sacramentality present in this song — where Springsteen sings about regaining faith in God’s mercy at the birth of his son — bowls me over (despite its presence on Springsteen’s only thoroughly mediocre album).

And this is just scratching the surface. I’m glad your search is leading you deeper into Mr. Springsteen’s music. Very little pop music deserves to be taken seriously as art. Springsteen is very much the exception.

Jeff Taylor

Very true. Thank you.

Clown George

Mr. Butler,

Bruce was just on my mind over the last few days for some of the reasons you bring up in this great piece. First somebody on Facebook was lamenting that there weren’t very many good songs written about 9/11, and I begged to differ by bringing up “The Rising.”

I had always been a big fan of his 70s-80s material, but by the middle of the last decade, I hadn’t really paid any attention to his stuff for several years. Then one day in 2007, my friend scored me and my girlfriend tickets to one of his shows. I figured I should check out his newer stuff, at least so I’d recognize some of the material he was bound to play. I didn’t expect to be moved as much as I was. By “The Rising” in particular, but also by some of the songs on “Magic” – “Long Walk Home” ranks up there with some of his best tunes, and I think it captures a good deal of what FPR is all about and how far our country has moved away from those ideas:

My father said “Son, we’re lucky in this town,

It’s a beautiful place to be born.

It just wraps its arms around you,

Nobody crowds you and nobody goes it alone”

“Your flag flyin’ over the courthouse

Means certain things are set in stone.

Who we are, what we’ll do and what we won’t”

It’s gonna be a long walk home.

And then I was discussing with friends exactly what you say about Springsteen’s politics versus his art. He’s definitely a lefty, but there is a refreshing lack of politicizing in the lyrics of his best “topical” songs, and I think “The Rising” and “Nebraska” are the best examples of this.

Would write more, but gotta get back to work. Thanks for the article.

RockLibertyWarrior

Great article, I have always had the same opinion of “The Boss”. One thing I have never outgrown from my teenage years is the love of good rock n’ roll, you can tell that by my name. I have outgrown alot of things but music has got me through some tough times and certain songs actually remind me of the place and community I grew up in, that is by no means a bad thing at all. Sometimes I forget living in the city what it was like to live in a small town, then some song from when I was younger comes on the radio and I remember all the virtue and good things that came from living in that place. Sometimes tears spring to my eyes, sometimes I laugh and smile. “The Boss” is expert at this, even though we might not agree on everything political, we agree on most things.

Comments are closed.