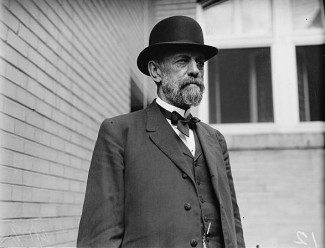

Sioux Center, Iowa. Thursday I toured the home of Richard F. Pettigrew, South Dakota’s original representative in Washington. The Victorian house was interesting, with some beautiful features, but I was drawn to the museum in Sioux Falls because Pettigrew is one of my political heroes. What other former Republican member of the U.S. Senate would write a book published by a socialist cooperative? His book, entitled Imperial Washington and published by Charles H. Kerr of Chicago, featured a blurb on the front cover saying, “It is a great book.” The blurb writer? Nikolai Lenin. Another first—and last—for a former GOP politician, I’m guessing.

I’m no fan of Lenin. He was a tyrant who unleashed a tidal wave of misery and evil in the world, but there’s something admirable about the radicalness of Pettigrew, who was so far outside the rotten mainstream of American politics that he could attract and was willing to advertise such praise. And in 1922 it was not yet clear how bad Lenin was, at least from a distance. As Orwell pointed out in Animal Farm, the communists of the East were not so different from the super-capitalists of the West, but the Bolshevik leader paid lip service to a rejection of plutocracy. Pettigrew’s book was originally called Triumphant Plutocracy—an accurate description of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Opportunist that he was, Lenin was likely trying to piggyback on genuine populist sentiment in our nation as a means of promoting the new Communist Party USA. But Pettigrew was the real deal. His commitment to principle trumped loyalty to party. He began as a Republican, jumped ship over the currency issue and became a Silver Republican, was briefly a Populist, and ended up as a Democrat. A Democrat who eventually hung out with socialists. En route, he backed William Jennings Bryan, William Randolph Hearst, and Champ Clark for president. He never trusted Woodrow Wilson.

Senator Pettigrew wasn’t a fuzzy-headed idealist lacking experience in the real world. Nineteenth-century state legislatures didn’t send proto-hippies to the U.S. Senate. He was a lawyer and real estate developer who helped build his local community by attracting railroad and milling business to southeast Dakota. In Washington, this realist saw the effects of high-level crony capitalism up close. It was one reason he opposed imperialism just as the American Empire arose. He denounced the annexation of Hawaii in 1898.

Pettigrew’s opposition to World War I led to federal prosecution for violating the Espionage Act. His legal team, led by his friend Clarence Darrow, succeeded in getting the charge dismissed but the fact that an ex-Senate member was even charged—and the same thing was happening to scores of the un-famous—is one of many things that make Wilson the worst president in U.S. history. I saw the indictment of Pettigrew framed and hanging on the wall of his house. He stipulated in his will that the indictment must be posted next to a framed copy of the Declaration of Independence. It still is. When Republican bosses back home grew tired of his anti-establishment stances, they set him aside. He spent a little time in New York but returned to Sioux Falls and spent the rest of his life there.

Wilson’s Espionage Act was a bad gift that keeps on giving. The law sparked landmark Supreme Court decisions enshrining the principle that speech is free except when the government deems it unhelpful (to the government). Daniel Ellsberg was charged under the law. Now it’s Bradley Manning’s turn. Who are the Pettigrews today? We still need them.

23 comments

Siarlys Jenkins

This is a useful discussion, because we are identifying unexpected points of commonality, as well as putting differences into sharper focus. I’m always inclined to learn more about the Cooperative Commonwealth, and I will see if I can find time for the Hoosier book as well. I suppose the founding of Arkansas is as good an example as I can think of for the entrenchment of an elite. I haven’t studied this in depth, but I’ve read that the politics and land ownership in the state was initially dominated by about six families.

I was just thinking the same about the Founders… its a good thing neither side won. In fact, Hamilton getting a framework set up, then Jefferson getting to take it over, pare it back, change its direction, may be the best initial sequence we could have hoped for.

John Gorentz

“not so many of them had not had their way over powerless slaves.”

Should have read, “not so many of them had had their way…”

Siarlys Jenkins

I find it a bit facile to describe a variety of class and non-class conflicts through the late 19th and early centuries as “a continuation of the Hamilton v. Jefferson debates.” Both men were rather more complex than their admirers or detractors will admit, and it is difficult to trace consistent adherence to either of their programs in later conflicts. Jefferson, after all, is the one who pushed through the Louisiana Purchase, arguably without any constitutional authority to do so. He certainly wasn’t above using federal power for the ends he had in view.

Madison is an interesting counter-point. When the first proposal for a National Highway was made, Madison observed that he could find no authority in the constitution for the federal government to do that, but thought it a good idea, and suggested that the constitution should be amended to grant that authority.

I think it might be more accurate to say that local gentry and entrenched interests preferred local control and a more agrarian society, because that preserved their own role as dominant fish in small ponds. Like quasi-feudal dominant classes everywhere, they could turn out their loyal retainers, generally people they had kept working hard and not too well read, to support the status quo.

I hardly see how railroads could contribute much to any national or community prosperity without being interstate. There weren’t enough consumers in Texas to consume all the beef the state was producing. Etc. While I think Wickard was an over-reach, and I was thankful for the Rehnquist court’s timely reminder in Lopez that the interstate commerce clause does not support a plenary police power for the federal legislature, I consider federal regulation of actual commercial activity to be unavoidable, because our economy is in fact almost entirely interstate at this time. It is proper that, e.g., only interstate shipments of milk are subject to federal regulation, while states may permit local or intra state sales of raw milk, even if its virtues are, in my opinion, hyped and illusory. You are in a limited scheme of government quite free to pursue hyped or illusory purposes, so long as they do not become mandatory.

John Gorentz

Siarlys Jenkins, you are certainly correct that no successor groups consistently adhered to either the Jeffersonian or Hamiltonian programs. There have been shifting alliances all along. But the debates never ended, and still haven’t ended as far as I know. That is probably a good thing, because it would be terrible if one side or the other gained a complete victory or suffered a complete defeat. It is the unresolvable standoff between the two that gives us a little room in which to live. (I often call Hamilton our Founding Fascist. I wish I had an equally odious name for Jefferson. One of the greatest things about the Founders is that none of them won and had their way. They would have been even greater if not so many of them had not had their way over powerless slaves.)

As for your statement about local gentry and entrenched interests, you have your history backwards in the case of southern Indiana or the parts of the midwest where I grew up. There are cases where your description fits, but it doesn’t fit as a general rule. You really ought to read Nation’s book.

Another book that I found helpful in understanding some of the populist movements of the late 19th century is “Cooperative Commonwealth: Co-ops in Rural Minnesota, 1859-1939.” (2000) by Stephen Keillor. (After I finished it I learned it was Garrison’s brother. Garrison is an accomplished radio guy, but his books are bleh. This book by his brother was fascinating. This reminds me that I need to read some of the others he wrote.) One of the reasons I was reminded of this book is because of the way expanded markets for dairy products (thanks to railroads and, later, refrigeration) brought about safety and health regulations and in some cases, a lowering of quality of the dairy products that were sent to mass markets.

Siarlys Jenkins

I think we have a point in common there John. Whenever I hear of a body like “The Committee of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws” I cringe, because there is, across the board, no reason states should have uniform laws.

There is a place for uniformity. If we’re all going to drive on freeways from Iowa to Mississippi or DC to Wisconsin or Ohio to Kansas, there should be some reasonable predictability for what behavior is expected of motorists — and the little details, like whether the speed limit is 55 or 75, can be posted. But just because New York requires booster seats for kids under 100 pounds is no reason Nebraska should do so.

I think your history is a bit shallow. Abraham Lincoln grew up watching his father remain dirt poor because he had no way to get his surplus crops to market over the unreliable dirt roads available to him. Lincoln saw, not incorrectly, that railroads would improve prosperity for farmers — or they would have, if not for the rates railroads charged to move crops to market.

Going back to no railroads at all would not have been good for farmers. Instead, they demanded regulation of the big bad railroads. A single state couldn’t do that. IT was interstate commerce, and state legislators could be bought cheap. Of course for a larger sum, so could congressmen, but it was easier to buy legislators to elect the right senators, which is why there was an outcry for popular election of senators.

Nothing is simple. Anarchy is the mother of gang warfare, and gang warfare is the mother of The State, which is the mother of wars. That’s basically the argument for ordered liberty, but getting the order part right and still having liberty, that’s a bear.

John Gorentz

Lincoln grew up poor. So did people who took the opposite side, back in the days when the federal role in what was called “internal improvements” were being debated. In fact, it was generally a poorer element in society that didn’t want the prosperity that was being advocated by the progressives of the day.

A book that I found helpful is, “At Home in the Hoosier Hills : Agriculture, Politics, and Religion in Southern Indiana, 1810-1870″ by Richard F. Nation (2005). It analyzes those who favored a progressive program to use federal funds to improve transportation and make the U.S. into a commercial society, vs those who preferred local control and a more agrarian society. It was a continuation of the Hamilton vs Jefferson debates. And all the terrible things each side accused the other of were true, at least in their general tendencies if not in the details.

As railroads expanded, they couldn’t become interstate in the way the biggest industrialists wanted, without federal usurpation of state regulation. They still could have contributed greatly to national and community prosperity without that, though.

Siarlys Jenkins

OK John, I’ll buy that. And the alternative course of mitigation is…???

John Gorentz

OK John, I’ll buy that. And the alternative course of mitigation is…???

Here’s one item for starters: “Crazy patchwork of state and local regulations” is a good thing, not a bad thing.

An Illinois railroad lawyer named Lincoln worked to remove some of the crazy patchwork of regulations of his day. The result: railroads grew big, consolidated, became efficient, and became too powerful.

John Gorentz

And the solution is…???

We conservatives don’t do solutions. We are suspicious of people who do, if we don’t outright fear and loath them. (Like that guy who had a final solution.)

We do mitigations, not solutions.

Jeffry Butter

Thanks for reminding us of Pettigrew. But you’re wrong about Manning … he is not a patriot.

Siarlys Jenkins

During Lenin’s periods of exile, he sometimes signed communications “N.Lenin.” Nobody is quite sure what it meant. That was somehow extrapolated to mean Nikolai Lenin, but there is no clear record Lenin ever adopted the name. Lenin, of course, was a revolutionary nom de guerre. He was born Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov. His most famous older brother, Alexander Ulyanov, was a Narodnya Volya adherent (variously translated People’s Will or People’s Liberty — in eastern cultures the two are often conflated), who was hanged for a plot to assassinate the Tsar. In any event, some early publications, especially by non-Russian publishers, give his name as Nikolai Lenin.

Having offered some elucidation on that question, I am inclined to wonder what Pettigrew would have thought of Lenin’s The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky. Of course the title sounds heavy-handed to modern enlightened ears, but I once found it as amusing a read as a good episode of The Daily Show. Pettigrew seems to have been a practical business man, who would have little patience with airy fantasies, and Lenin had something of the same attitude toward vapid politicos. Pettigrew might have called it a good book. Lenin had a practical side. I once ran across reference to a note to his central committee saying “Put me down in favor of accepting coal, guns, and potatoes from the Anglo-French Imperialist butchers.”

Jeff Taylor

Paul, I know what you’re saying, but yes, his name appears on the book jacket of the first edition as “Nikolai Lenin.” You can see it rendered the same way in a literary sketch from the same time period here: http://www.marxists.org/archive/bryant/works/1923-mom/lenin.htm

Paul Hughes

Was Vladimir Lenin also called Nikolai? I read that he had a brother Nikolai who died in infancy, and a grandfather named Nikolai, and went under the pseudonym Nikolai (with a different surname). I didn’t know he was actually (also) known as Nikolai Lenin.

Siarlys Jenkins

It’s too bad that people like Pettigrew who were perceptive enough to see where the concentrated wealth and power of centralized industry was taking us weren’t also perceptive enough to realize they were exchanging a bunch of big bullies for an even bigger bully who would do more of the same, only worse.

And the solution is…???

There is a good deal that can be done to break “too big to fail” down to “small enough to let them sink or swim” that hasn’t been done, but some common institution has to do the breaking, and has to exercise judgment about what to break, when, and how.

Too often, the argument against “Big Government” is being manipulated by large corporate interests posing as pseudo-populists, all the while saying “Pay no attention to that Plutocrat behind the curtain.” If New Deal alphabet soup agencies aren’t the answer, and communist collectivist class struggle isn’t the answer… it seems we need to come up with an answer we don’t yet have.

When I see John Medaille and Russell Arben Fox agreeing on the Mondragon cooperative as a model, I have some hope there may be something to it. Ditto for the chemical factory in Poland that kept right on funding all the social services for the workers and their families they always had, because they were selling a product people wanted to buy and had the revenue to pay for it all, especially since their were no capitalist stockholders. But the “gummint camps” for the Okies in California weren’t all bad — they were a pretty good idea and there should have been a lot more of them, financed by a tax on the growers who wouldn’t pay decent wages.

Its true that dams engendered problems nobody had really thought about. So did plowing up the Great Plains for agriculture. We live and learn, sort of.

Kevin O'Keeffe

I was just in the Pettigrew Heights neighbourhood of Sioux falls (where his house is located) a couple of hours ago.

Thomas McCullough

I know Manning is a bit off subject, but I didn’t start it. I observe the obvious thing about all that I have heard from wikileaks that hasn’t been pointed out before to my knowledge. That is that nothing revealed is the least bit surprising. It’s all “Oh, yeah, that’s just what they’d do.”

robert m. peters

Mr. M.,

To be sure, based on the facts which we think to know, Mr. Manning has committed some act or acts which under military code and under certain federal statutes can be labeled felonious and for which he must be punished; however, there is little evidence which I have thus far seen to indicate that he has committed treason as defined by the drafters and ratifiers in that document which we call the Constitution.

“SECTION 3. Clause 1. Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open court.”

One commits treason against the sovereign states, that is why the clause clearly states, “their” enemies. Revealing information about a general government unconstitutionally operating in the international arena, pursuing the interests of the elites, factions and bureaucrats as well as the parasitic corporations is hardly treason against the states. It would seem that in terms of treason the shoe is on the other foot, the foot of the factions which have usurped the power of the general government to their own ends rather than to the genuine interests of the states and the respective people therein residing.

Paul M.

Bradley Manning is vastly different. Manning is on trial for at best, mishandling of classified information, and at worst, treason for abetting the enemy. He knew the consequences of his actions because the government makes it abundantly clear when an individual is entrusted with a security clearance. If what he did was an act of civil disobedience then he must accept the consequences.

Judging Manning by the principle, he should be found guilty.

John Gorentz

It’s too bad that people like Pettigrew who were perceptive enough to see where the concentrated wealth and power of centralized industry was taking us weren’t also perceptive enough to realize they were exchanging a bunch of big bullies for an even bigger bully who would do more of the same, only worse.

BTW, I’m reading an abridged version of one of his books, which is available online at archive.org: http://archive.org/details/chaptersfromimpe00pettrich . It’s apparently an abridgement done by Pettigrew himself.

I’ve learned that Pettigrew was in favor of dam projects on the Missouri well before the Pick-Sloan Missouri Reclamation project. Some of my years as a kiddie were spent in the vicinity of some of these projects. One of my earliest recollections was of being taken to sites where archaeologists were trying to do what work they could before the reservoir waters came. I was too young to understand what we were seeing, but I understood a bit more when Pres. Eisenhower came out to dedicate the Garrison dam in 1954. I have several memories of that day.

Some of the environmental downside of these projects was being discussed in our family even before people learned the word environment as it is currently used. I’ve also found it interesting that there are still lingering resentments of what happened to the people and communities displaced by TVA dams in Kentucky and Tennessee, and by the Army Corps of Engineer Dams on the Wabash tributaries in Indiana.

Tonight, in looking for more reading material on this subject, I found “Dammed Indians Revisited: The Continuing History of the Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux” (http://www.amazon.com/Dammed-Indians-Revisited-Continuing-Pick-Sloan/dp/0979894018). Hope to read it soon.

There are echos in my family history that go back to the days when Pettigrew was active in politics. Apparently a great-grandfather, having homesteaded in North Dakot in the early 1900s, was involved in some of the anti-railroad-elevator agitation of that time. I also need to learn more about why a grandfather who first voted for William Jennings Bryan and later for FDR was by the time I knew him, outspokenly anti-FDR, anti-socialist, anti-communist, anti-New Deal, and refused to take social security even though he needed the money more than anyone else I knew. And I need to question my parents more about their transition from voting for FDR to being so staunchly anti-FDR that the only time Dad questioned the reading material I brought home from the library was when he was concerned that I was reading some FDR stuff that might not be good for me. (He doesn’t remember that incident, but I do.)

So I like to understand more about people like Pettigrew and to learn what made them tick. I have considerably sympathy with their reactions to the changes in American society and political life. I also look with horror at the changes that came about through their advocacy.

robert m. peters

I am sure that Lenin noticed and applauded the dialectic evolution evident in the life and political understanding of Senator Pettigrew. Lenin and those of his ilk, however, schemed to accelerate that dialect evolution toward an idealized and ideological (same root) condition of the commune, noting that their commune is a counterfeit commune more appropriately called the collective, by using the organs of the centralized state to mass murder, systematically torture and labor-force incarcerate as means of coercing those who did not get with the program. Here and in other ways, Lenin and his sputniks diverged quite a bit, it would seem, from the Senator Pettigrew as he is presented in the article supra.

Siarlys Jenkins

My education and political reading has a sad deficiency. I’ve never heard of this guy. I’ve been to the Eugene Debs home in Terre Haute. I must read up on Pettigrew.

I have a bit more admiration for Lenin. I don’t think he was piggybacking on anything. He found himself immersed in a movement of proto-hippie-dippie intellectual revolutionists, and sought a realistic way to actually seize power and put a program into action. He did somewhat better than my more pristine heroes, the Populists of 1892 and the man they wanted to run for president in 1896, Eugene V. Debs, all of whom were successfully sidelined.

Lenin certainly had too much faith in himself, building an entire organization around the notion that “I know what I’m doing, so if everyone follows my orders, we will win, otherwise, we’re going nowhere.” He lost sight of James Madison’s wise observation that enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm, so government (or even internal party rules) can’t be based on the assumption that they will. The theory was, strict party discipline insures fidelity to original founding principles, in the face of opportunism and corruption. It doesn’t. It insures fidelity to anyone who gets the top spot, no matter how corrupt or self-serving. The world’s largest remaining communist party is now administering the world’s most ruthless capitalist economy.

Another fact, which socialists having no experience of power couldn’t visualize, is that to manage an economic enterprise is to be subject to certain natural pressures, including trying to press the workforce to get the most done as fast as possible for the least expense. Turns out those pressures apply to socialist managers as well as capitalist managers, especially during a period of crash development and capital accumulation. These are natural pressures, but in an economy dedicated to serving people rather than using people as servants of the machine, these natural pressures need to be regulated, controlled, restrained, moderated, and perhaps even taxed. A medal for being a hero of labor is no substitute for time-and-a-half, while being blacklisted is a bit more comfortable than being shot as an enemy of the people.

It is seldom remembered that the Progressive movement grew out of the Republican Party, including Norris, La Follette, and apparently Pettigrew as well. Woodrow Wilson is the president who sent Eugene Debs to prison for quoting one of Wilson’s own pre-war promises at a public rally. Warren Harding is the president who commuted Debs’s sentence and sent him home. Debs may be the only federal prisoner to have ever been granted a limited parole to travel unescorted by passenger train to Washington to meet the president at the White House, on his promise to then return by the same means to the Atlanta penitentiary. I recently had occasion to refer to Wilson as “the arch-segregationist progressive Democrat,” in an article on the last time voters of African descent gave 40 percent of their votes to a Republican (1956). Wilson segregated a previously unsegregated federal civil service.

Can we expect another like Pettigrew out of South Dakota any time soon?

John Gorentz

Never mind. It’s probably a different Augustana College.

John Gorentz

Interesting. It looks like anyone wanting to do research on the guy could make a trip to Augustana College, which has a copy (or the originals, I’m not sure which) of his wife’s family papers. IIRC, a portion of the Front Porch is located at Augustana College.

Comments are closed.