Berwyn, PA. Last week, I reprinted a version of “At Bar Harbor Once, and Once . . .”, which appears in the new issue of Modern Age. As I mentioned then, it comes from a series of meditative lyrics on Ireland, history, and the problem of knowledge, several of which have been published or are forthcoming in the same magazine. Below, I reprint a much revised version of “On a Sculpture by Herbert Adams,” which was published in Modern Age several years ago. I include, also, the artworks referred to in the poem and, at the end, a copy of the notes I included in a small booklet of the poem, which I had printed to share with a few friends at a time when I could be absolutely certainly nobody else would want to read my verse.

~

American Beauty Exhibition,

National Gallery, Dublin

July 15, 2002

I

The precise anger in your eyes, last night,

Seemed for the first time and, perhaps, the last,

To cut through every fold of charm, and sight

In me the creased rags of a sordid past.

“For too long now,” you said, “I’ve thought you were

Not perfect but, at least, what you said you were.”

This afternoon, expatriated from

Our homes, our images, our usual selves,

We neither speak nor touch. The gallery’s hum

Of scrubbed dry air, and the exhibited wealths

Preserve our silence: artificial world,

Where what you said distills, abstract and cold.

You stare at the volcanic Cotopaxi,

Those oils flooding toward apocalypse.

But that, or any sublime scene, turns warily

On our few months abroad as they collapse.

I go from work to work, continue down,

Till my thoughts rest upon a girl of stone:

II

Her marble eyes, up close, are clumsy things,

Vertical scratches form an iris, light

Brushwork of paint upon them browns to bring

Definition amid the consummate

Polish of a pale and laminate cheek,

Whose model sat for Adams one snow-locked week.

But from a middle-distance, eye and neck,

Flowering cheek and pied jewelry,

Her unmoved glistening lips seem to enact,

In cold perfection, warm reality.

Did that young lady on her sculpture stare

Preferring it to her face in a mirror?

This piece, some fifty others from Detroit,

Like us have come to Dublin for a time,

And looking on them here gives each a slight

Fraternal kinship we would never find

If we walked by them in that old museum’s

Muted familiarity of home.

III

For Adams and his peers the trade of art

Must have itself seemed an imported thing:

Threatening, rarified, and set apart

Like thorned peaks of the Swiss Alps rupturing

Above the folded skin of clouds. They ripened

Such borrowed fancies to an archetype.

So, too, that Boston heiress took the lot

To line her corridors of Italian stone.

Her gardens flourish near old pictures bought

From needy seigneurs in a rotting Rome.

For that servile gift she will be ever praised

Though Rembrandt hasn’t yet been “naturalized.”

Cross town, this genteel figure held her pose

Till all the academic strains of time

Had found, in Adams’ hand, a tense repose.

His predecessors helped him see a line

(At least he hoped) in that too living flesh,

And haunted his work into consciousness.

Most difficult work is undergone in fear

Of some misunderstood authority

Whose echoed voice, despite itself, doesn’t tear

Obedience from originality:

The distance of a carpet’s breadth or sea’s

Leaves room for brilliance in naïveté.

IV

And yet, on this isle more than any other,

Remembering the five pounds Victoria gave,

And how she came, purblind and ruffled visitor,

But once, carried above the hungry graves,

I know that a small channel’s distance lends

Space enough for a murderous ignorance.

The woman standing by me now, as we

Stare on an ageless face whose model has

Long ago passed into her grave, may be

The one who fashioned my best self from ash.

She trusted my words and her eyes to see

What only is while wish meets novelty.

I don’t, for that, dare touch her idle hand,

Or peer again into that emptied eye,

But wonder why we come to understand

What grips us more than other passers-by

As disappointing just because it held

Our stare longer than casual stares are held.

Adams discerned as much and set his girl

Upon a high and ornate pedestal

Till saved in stone from a decaying world

She seemed but scarcely individual.

And yet, I love her painted uncombed hair

Because I found some imperfection there.

I’ve often tried to hold an endless breath

Between a dawning thought and regret’s instance:

As love and hate, to stall a candid death,

Must idle as they can at middle-distance,

By chance discovering what we all must know:

That intimate knowledge comes as a sudden blow.

~

NOTES

A leading sculptor of the Renaissance Revival movement, Herbert Adams (1858-1945) was born in Concord, Vermont at a time when American sculptors were turning away from antiquities to modern subjects and methods. He studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was a student at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Adams actually rendered his “Portrait of a Young Lady” (1903) in Paris rather than Boston as the poem suggests. Also, early American landscape painters tended to use the Swiss Alps as a model of the sublime, even when they were nominally painting American mountainscapes. Hence the importation of the practice of art was not merely one of artists’ training abroad; they were also importing imaginatively European subjects and projecting them onto their vision of America.

At 18,858 feet (5748 m) Cotopaxi was the most impressive of the South American volcanoes; its cone was considered particularly perfect. The New York collector James Lenox commissioned this view in 1861. By that date the Civil War had begun, and Frederic Edwin Church’s (1826-1900) decision to depict an eruption has been interpreted as a direct reflection on the tragic turn of events. The rising sun is obscured by the smoke of nature ‘at war with itself’, and the landscape shows the world ‘evolving out of the simultaneous processes of creation and destruction’.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924), was one of the foremost female patrons of the arts. She was a patron and friend of leading artists and writers of her time, including John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler and Henry James. She was also the visionary creator of what remains one of the most remarkable and intimate collections of art in the world today and a dynamic supporter of artists of her time, encouraging music, literature, dance and creative thinking across artistic disciplines.

Over three decades, Isabella Stewart Gardner traveled the world and worked with important art patrons and advisors Bernard Berenson and Okakura Kakuzo to amass a remarkable collection of master and decorative arts. In 1903, she completed the construction of Fenway Court in Boston to house her collection and provide a vital place for Americans to access and enjoy important works of art.

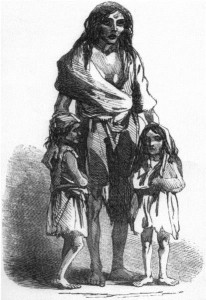

During the Irish Potato Famine (1845-49), Queen Victoria supposedly donated 5₤ toward relief for the thousands of starving Irish. This would seem to be apocryphal, but captures allegorically the history of mismanagement, repression and neglect that characterizes the British colonial experiment in Ireland.