The creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God. (Rom. 8:21)

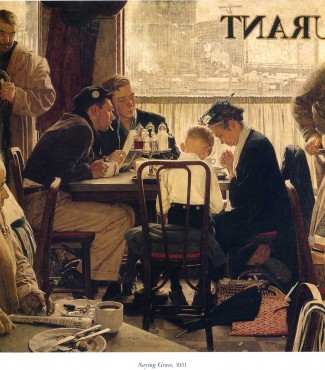

I am looking at Saying Grace, an extraordinary painting by Norman Rockwell.

I’ve never caught the bug for despising beautiful things, or dabbling in the hideous. I cannot, nor do I wish to, learn not to look in art for beauty, intelligence, consummate skill, human feeling, and truth. So I am looking at Rockwell’s painting, and I don’t care who knows it.

It’s a cluttered, slovenly restaurant at a railway station. An old lady with a crumpled green old lady’s hat – the daisy in front is a fine touch of freshness and open air in these stuffy quarters – sits at a table, her head bowed and her skinny bony hands clasped in prayer. Her grandson sits beside her, his back to the viewer. He’s got close cropped red hair and the tad-too-big ears that tug at a mother’s heart. His head is bowed, too, and the set of his shoulders and arms suggests that he too has his hands clasped. He’s leaning slightly toward Grandma. He’s taken off his hat, a gray bowler with a small red cockade. It lies below with an umbrella and Grandma’s bags. He looks very much like a little man, and that’s quite right, because the other figures in the painting are men.

Those men are drawn to the scene of prayer. We don’t know why. One of them, seated in the foreground, glances askance at them, a cigar in his left hand, a rolled up newspaper on the table, with a saucer of cigarette butts and a plate full of the broken remnants of his lunch. He’s laid his knife and fork across the remnants as if to say, “That’s it, to hell with the rest.” Another man, with a hard-bitten face, knits his brows and looks down at them, his mouth pressed tight in an expression that I can only describe as a grimace of distant approval. But the really dramatic figures are the two young men who are seated at the same table with the grandmother and the grandson. One leans forward, clutching his coffee cup, as if caught by surprise. A cigarette dangles from his lips. The other, a reddish blond, and exceptionally good looking but in a sad transient sort of way, leans toward his friend, while gazing at the couple, in rapt attention. He could have been that boy, long ago. He is holding a cigarette in his right hand, and the smoke rises up in a thin white wisp between him and his friend.

On one side of the table, silent words and prayers rise up to God, in thanksgiving for the very ordinary meal. On the other side, moral embarrassment, and cigarette smoke.

There is not the slightest sense of ostentation in the grandma and the boy. Their bodies suggest they are for one another and for God. Yet in their simple piety they create a space of profound freedom. They are in the railway station, and not in the railway station. They are both comfortable where they are – they do not seem the least bit tense or wary or self-conscious – and they are going somewhere, while the men in the painting appear to have gotten stuck. In fact, they seem to have forgotten themselves entirely, surely the sweetest freedom of all. If the men were not also struck in the heart, I might say that the lady and the boy had entered a den of thieves and turned it into a house of prayer.

What is it that people fear so much about prayer? When our schools were built to resemble the churches or the town halls of a free people, it was taken for granted that there would be prayer. What would a dance be without music? The spires were like jousting lances in a tournament against the sky. They aimed high, because their hearts were high. They freely gave what they had freely received. They need not bow to any prince, to any system of government, to any worldly army, or to any cabal of men conspiring to clap them in bonds for the good of the state. To my mind there is nothing so free as a group of people, old and young, men and women and children, singing songs of praise from of old, to the glory of God. “Prayer and sacrifice,” says Chesterton, “are a liberty and an enlargement,” opening up the soul of man to the infinite God, and inviting Him to come and dwell among us, to have a local habitation and a name.

I think it is not accidental, then, that schools no longer resembled houses of prayer, or the town halls of a free people, which is to say a people open to God, about the time when prayer was sent packing from the schools, as if it were the prison and not the key, as if it were the cell and not the free heavens, as if it were the burden on the shoulders and not the promise of release, as if it were the cause of alienation and not of community. And, at the same time, we began to build schools that are all inside and no outside, all stone and no garden, all power and no humility, all hulking system and no small child, all gears and no flowers, all compulsion and no promise. The face gives witness to the life or the death within.

Suppose the proprietor of the restaurant had said, “I do not want my customers to be compelled to witness a moment of prayer. It might embarrass them. Therefore this will be a prayer-free restaurant. No Saying Grace Allowed.” Forget for a moment the small matter of civil license to think what you will and speak what you think. In what way could the restaurant possibly be held to be more truly free after the banishment of the public prayer?

In other words, remove the boy and his grandmother from Rockwell’s painting. What is left?

A seedy diner at a railway station, that is what’s left, and men abandoned to their compulsions. They smoke, they down coffees, they check the racetracks, they go to work they do not enjoy, they return to difficult homes, they hunt for women, they pursue whatever alleviates the weariness of a world with no heaven, which might as well be a world with no sky. But far away from the diner are men with the compulsion and the financial and political might to rule. For it is some consolation, if one must be whipped, to ply the whip oneself, in a terrible parody of the words of the Lord, that it is better to give than to receive. Thus will the powers that be, set free from freedom, rule without constraint or scruples. It is absolutely astounding how many miserable compulsions a degraded people will tamely and timidly endure, if only to be relieved of the threat of prayer. Having dwelt so long underground, they fear the open blue.

I have long been thinking that the only tonic for these sick people is the freedom shown by the old lady and the boy in the picture. It is the freedom of being entirely open to God and thus entirely open to man, open to the point of nakedness. Grandma and grandson are weak and vulnerable, in their forms and in their sweet freedom, but where I am weak, says Saint Paul, there am I strong. If people run from freedom, then let freedom stride happily into their midst. If people will not listen to reason, let them listen to song.

Faith in men is for slaves. Faith in man is for fools. Faith in God is for men.

6 comments

Kenneth A. Cote, Jr.

Pardon my typos. I wrote my comments on an iPhone–big fingers, little keyboard.

Kenneth A. Cote, Jr.

I have a smidgen of good news. I teach in a public high school in a small Connecticut town with a predominantly Catholic population. Every Chistmas season the secretaries decorate the front office with a small tree and a smattering of stockings, garlands, and Santas; they include nothing overtly religious, preferring to stop just shy of Constitutional boundaries instead of risking the loss of their modest tradition. A few teachers even run an informal contest among their home rooms for the most festive array of lights and decorations. Not one person has compained since I was hired 21 years ago. Of course, my writing about it has probably activated some curse–such is life’s bitter irony. At this point, however, we are fortunate to enjoy a pleasant little shiver of joy each December–a sprig of evergreen for the heart.

andrew

I’ve enjoyed the entire series so far, Prof. Esolen, and thank you for your reply.

Tony Esolen

Andrew: A good question. I might turn it back to you: what exactly was done in schools in which there were a goodly number of Jewish children? Jewish people in the northeast were great promoters of the public schools, and I hardly think that they would have been, unless some comfortable and mutually acceptable modus vivendi had been reached between them and the largely Protestant Christians who made up the rest of the school.

That’s the thing — ordinary people, when they are responsible for their own towns and schools, have no particular desire to offend their neighbors; and, conversely, their neighbors have no desire to take offense or to pretend to take offense when none is intended. I have little doubt that the Protestants at Stuyvesant High wanted the Jewish kids to be more, not less, faithful to Judaism; and that Jewish teachers encouraged the same faithfulness in their Protestant students. My mother tells me that once a week, the Catholic students from the high school in our home town were trooped across the street for catechetical instruction; the public school teachers made sure that they went. The Protestant students, of course, didn’t have to go, and so they just went straight home.

What the Supreme Court snatched away from us — and has been snatching away, for sixty years — was not just an old and revered tradition to which no faithful Jews, Protestants, or Catholics in the public schools objected, but the capacity to govern ourselves, by our own best lights. I’m sure that what they did in PS 42 was different from what they did in Archbald, Pennsylvania, but that’s fine, because the Bronx was not Archbald.

Imagine, just imagine what it would be like, if the feds and the judges stayed the hell out of the schools, where they don’t at all belong, and imagine if the state capitols set broad guidelines, but otherwise left the parents and the teachers in each school to determine what would go on there … That’s what we had, until the onslaught of mass-produced textbooks and increasing control of education by the teachers’ unions, the state legislatures, and the graduates of the Normal Schools, trained in the latest Deweyite fad. If you want something that will make you reach for the gin bottle, pick up any 100 year old issue of a local newspaper, or of the more literate magazines, such as The Century or Scribner’s or, heck, even The Ladies’ Home Journal. Very sad …. Our schools used to produce people who were genuinely literate.

andrew

I agree that we are largely a degraded, sick people. (I just watched Roger Scruton’s short documentary “Why Beauty Matters” this weekend and was pleasantly reassured that not all is lost yet.) But suppose a Jewish student attends a public school and is made to recite the Lord’s Prayer. Wouldn’t that be “compulsion?”

Justin Gregory

My wife and I wondered why they had built a penitentiary in the middle of our residential neighborhood, until we realized that it was the local middle school. I was inside it a few weeks ago to judge a science fair. (All students were compelled to participate; it was as disastrous as you might expect.) The hallways were tall and narrow, with bare cinder block walls and fluorescent lighting high above.

I have nothing against public schooling in principle, but my wife has long favored homeschooling, and I’m starting to come around to her way of thinking.

Comments are closed.