Let us suppose we are confronted with a desperate thing– say Pimlico… It is not enough for a man to disapprove of Pimlico: in that case he will merely cut his throat or move to Chelsea. Nor, certainly, is it enough for a man to approve of Pimlico: for then it will remain Pimlico, which would be awful. The only way out of it seems to be for somebody to love Pimlico… –GK Chesterton

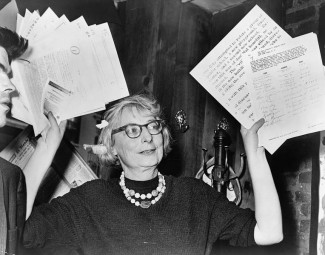

You could call her a Front Stoop Republican.

Jane Jacobs, best known for her epic battle against Robert Moses’ attempt to build an expressway across the tip of lower Manhattan, had come by this fight honestly. A journalist and a lover of her own neighborhood– the un-gentrified Greenwich Village of the mid-twentieth century, where she shopped and drank and raised her children– Jacobs set out to investigate what makes cities work: what makes one neighborhood lively, safe, and humane while another one is shriveled, dangerous, and boring. Her investigations, which became her first book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, led her to conclusions that contradicted every piece of city planning wisdom being taught uptown at Columbia.

The primary evil that urban planning was seeking to address at the time was what was called the “problem of urban blight:” slums. The cure, in 1954, for “urban blight” was “urban renewal,” code for knocking down slums, and constructing developments of very tall poured-concrete buildings. The ex-slum dwellers were then installed in modern apartments and instructed to send their children out to play on the very large, treeless squares of parched lawn that were inserted into the middle of these developments. These complexes were mashups of several different ideas about what makes good urban design, and belonged to what might be called the Radiant Garden City Beautiful of Tomorrow school, to which Jacobs was constitutionally allergic.

And yet she did not– could not– pretend that slums themselves were desirable. What she did was observe how slums actually got better: and the process that she noted was something like healing from an illness. “The foundation for unslumming,” she wrote,

is a slum lively enough to be able to enjoy city public life and sidewalk safety. The worst foundation is the dull kind of place that makes slums, instead of unmaking them. Why slum dwellers should stay in a slum by choice… has to do with the most personal content of their lives, in realms which planners and city designers can never directly reach and manipulate– nor should want to manipulate. The choice has much to do with the slum dwellers‘ personal attachments to other people, with the regard in which they believe they are held in the neighborhood… people who do stay in an unslumming slum, and improve their lot within the neighborhood, often profess an intense attachment to their street neighborhood. It is a big part of their life. They seem to think that their neighborhood is unique and irreplaceable in all the world, and remarkably valuable in spite of its shortcomings. In this they are correct, for the multitude of relationships and public characters that make up an animated city street neighborhood are always unique, intricate and have the value of the unreproducible original.

She was not against planning, or regulation, or political authority. What she loved was not the contextless assertion of individual will over private property, but the complexity and order of the good urban life. She was in favor of a very large amount of individual freedom in making decisions about property because she saw– not just believed based on abstract praxeological principal, but actually saw– that this was most likely to lead to livability. Order in a city, she finds, is something that emerges from the countless small decisions of house-proud citizens, living where they work, putting in a cat door or planting a tomato in a window box, minding their business and minding it with relish. This leads to an “ordered complexity” that is characteristic of living things.

But the business that each citizen minds must be the whole of his business– which includes the common good; Jacobs was convinced that what made for urban security was the presence of people who were keeping their eyes open, who believed what went on in the street to be, precisely, their business. We have heard about the art of citizenship. What Jacobs gives us is the craft of citizenship: something hands-on, open to all, requiring attention and apprenticeship and tactical wisdom.

She continued to write extensively, venturing into economics and ecology, but it was that first book that struck a nerve. Her influence can be seen today in James Howard Kunstler’s loathing of suburbia; in Philip Bess’ idea that mixed-use walkable neighborhoods are such a fundamental good that they belong in our thinking about natural law; even in Bill Bratton’s broken windows policing strategy, which seeks to prevent violent crime by promoting attention to beauty and order in the smallest physical details of a neighborhood.

The idea that one can impose a plan on a city without reference to its history or nature is a kind of urbanist positivism. Cities, under this conception, are what we will them to be. They are constrained neither by the universal “kind” of the City (which is only the Classical disguise worn by the New Jerusalem), nor by the particular history of that particular city.

Jacobs did not speak about natural law in this way, but through a kind of alert empiricism, she has– perhaps– discovered the other, corresponding kind of natural law in urbanism: the descriptive law that tells the story of how things that are healthy develop, and how things that are sick can heal. Attention to her observations can help all of us to become better practitioners of the craft of city living.

A Few Links

First, just go get the book: The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1993/1961,) available from your local bookseller.

The Preservation Institute has a small archive of Jacobs’ writing and other relevant material; see especially the interview that James Howard Kunstler did with Jacobs towards the end of her life: a phenomenal pairing of interviewer and subject.

And should you actually want to take action based on any of this, take a walk. Jane’s Walk promotes “urban literacy” in the spirit of Jacobs by organizing free walks, conducted by locals, in cities throughout the world. Jane Jacobs Walk, run by–I think– a different group, is apparently attempting to provide some healthy competition in the cutthroat world of urban sauntering promotion. Or, if you don’t want to wait until May, just grab a city map, a five dollar bill, a piece of chalk (for emergency hopscotch), and a good pair of shoes, and explore your place. And when you get home, loiter on your stoop, and consider what you see to be your business.

16 comments

Susannah Black

John– It’s still true– my Queens neighborhood is very much a village. The part of throwing parties in Queens that is so annoying (where people arrive at 9:30 for an 8pm party and they open their eyes wide and say “Queens is just so FAR AWAY!” as though they’ve been on the Oregon Trail instead of the F train) is actually a healthy sign. The incredible pride that people seem to feel in getting themselves to a cocktail party in one of the boroughs is a testimony to the feeling that you are actually visiting a different place. (My friends Tessa and Abbey, who live in The Place You Get To By Taking The PATH Train, can testify to the fact that it’s even worse for Jerseyites. And I have been guilty of being the drama queen who feels like getting to their apartment makes me some kind of badass Voortrekker who deserves a glass of chardonnay.)

Mr. Sabin– for you– http://shop.bybrooklyn.com/. I am particularly obsessed with the Gowanus Canal water bottle. I think I have a right to it, because I’ve actually taken some kids on a nature-observation row on the Gowanus, aka Brooklyn’s Coolest Superfund Site.

Gene Callahan

Mr. Sabin, I live in Brooklyn. The introduction of high rises in my neighborhood has been great for the mom-and-pop shops: more customers. You are looking at a false dichotomy.

D.W. Sabin

I’ll take the low rise air and sky of Brooklyn with its plethora of mom and pop businesses over the dark canyons of Manhattan with corporate commerce any day of the week.

Manhattan is invigorating, there is no doubt, but I’d rather repose where you can feel sky, air and shop in small independently owned establishments.

Siarlys Jenkins

I have not yet BEGUN to engage his arguments. Nor have you begun to offer any argument beyond “Gene Callahan admires Chakrabarti’s work and considers high rises perfectly liveable, also he thinkgs viewpoints considering low-rise buildings more liveable are mere prejudice.” After all, this is a blog, not a graduate course in urban planning. I MIGHT have found some really intriguing synopses of his work by googling him, but I didn’t. I found some fluffy PR puffs that could mean almost anything. There are millions of books in the world to be read, and only one lifetime to read them all, so I’ll take a closer look when I can. At this point, you’ve offered a plausible hypotheses, without data or or analysis to support it, and I have no basis to either accept or deny it. Is that so hard to understand?

Gene Callahan

I am using Siri to enter this text. So sorry it’s a little jumbled. Of course I meant to say “chakrabati’s character”.

Gene Callahan

Well, someone is seriasly testy! I was pointing to a good argument that high-rises don’t make for an unliveable city. If all you meant was “perhaps I’ll check that out one day” then you wouldn’t have drawn a response from me other than “okay.” But instead you chose to impugn character by implying he was just writing this to sell his own projects, and take a swipe at my blog in the process. So, no, “I might not have time to read this for a while” is not at all hard to understand. It is hard to understand is why you added the little nasty bits along with that.

Siarlys Jenkins

After googling Chakrabarti, I’ll take that as a maybe. After looking at your own blog, I’ll take that maybe with a medium size grain of salt. Maybe the prejudice that high-rise neighborhoods can be perfectly liveable is merely a convenient way to attract funding to Columbia. I’d have to take a hard look at those wonderful developments this guy designed before becoming academic. He certainly has a bias to start with, not that he couldn’t be right in any case.

Gene Callahan

Yes, Siarlys, googling him and sniffing around my blog are much better ways of deciding this issue than actually engaging his arguments.

Gene Callahan

Siarlys: “How do we preserve low-rise liveable neighborhoods…”

No need to do so: high-rise neighborhoods can be perfectly livable. See the work of Vishaan Chakrabarti, a big Jacobs fan: the prejudice that neighborhoods need to be low-rise to be livable is simply that: a prejudice.

RiverC

Christopher Alexander (the architect) has done some work to address this problem, the problem of land price / density in cities turning affordable living into anthills. Not that the planners were happy with his results (though the people who might live in such places were delighted with the designs and prices.)

It is certainly a case of ‘big idea’ modernists – even post-modernists are just modern modernists really – not wanting their imagined future to come crashing down because the salt of the earth are too bourgeois and parochial to care for their schemes.

I think the story in question about Chris Alexander was in Japan.

Siarlys Jenkins

Generally, I find Jane Jacobs heroic, but in Wrestling With Moses, Anthony Flint raises a salient question. How do we preserve low-rise liveable neighborhoods without them turning into high-priced gentrified preserves of the upper income elites? Moses and his staff were thinking, among other things, about how to house a growing population affordably. In a crowded city with gigantic real estate prices per square foot, a common response is to build high rises, which theoretically keeps rents and the cost of homeownership down.

Part of the answer is, if you plan for a huge increase in population, that will become a self-fulfilling prophecy, so stop doing it. But there are more spontaneous, or at least, non-governmental, forces at work. It would be good to disperse the population such that a larger proportion can live in low-rise neighborhoods with open squares and green space and spacious stoops. That might require Cantor Fitzgerald to settle for a nice new office park in Newark or Trenton or Atlantic City, rather than a prestigious location at the top of the World Trade Center. (It would have been healthier for a large number of the staff also).

This in turn might require a bit more government regulation, but carefully chose regulation that breaks tendencies toward centralization, while leaving space for ” the countless small decisions of house-proud citizens.” In fact, Greenwich Village is now a high-priced oasis the working class can no longer afford.

John Gorentz

Thank you for writing this. I wish I had learned about her much earlier in life.

D.W. Sabin

The Curse of Modernity is the slavish adoration of the Big Idea. Jane Jacobs preferred the little idea against all the various wrecking balls of the cult of Big Ideas. She had a great sense of humor, something that seems to be going the way of the Dodo

Jordan Smith

I was heading into my first year of Environmental Design at UBC when I read The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

A brilliant book. Her powers of observation were startling, the soundness of her thinking consistent, and the clarity of her prose was refreshing. It’s the kind of reading experience that leaves you thinking: Of course. That’s so obviously true. How come I didn’t see that?

Kind of like reading Wendell Berry.

Zach Frey

I can think of two suburban neighborhoods I’ve known where people know and care for each other. So counterexamples exist, but they are conspicuous by their rarity.

John Médaille

I had been serving as a councilman for about 10 years, and was well-versed by the city staff in the conventional “wisdom” of city planning, when I first read Jane Jacobs’ great work. I realized every single decision I had made in the last 10 years was wrong. The odd thing was, I should have known better from my own experience. I was born on 102nd street in Manhattan. Later we moved to one of those Moses developments in the Bronx where the results were, umm, mixed. Then we moved, like everybody else, to the suburbs of LA. Yet in 10 years of pompous pronouncements guided by our professional staff, it never once occurred to me to consult my own experience.

The truth about the “front stoop republic” is that a large city like New York manages to recreate the “village”; NYC is (or was) a collection of such villages, where people really did know and care for each other. The stoop on those brownstones were really a meeting place, a sort of mini-commons. This is something that never really happens in a suburb, or at least not any suburb I have lived in.

Comments are closed.