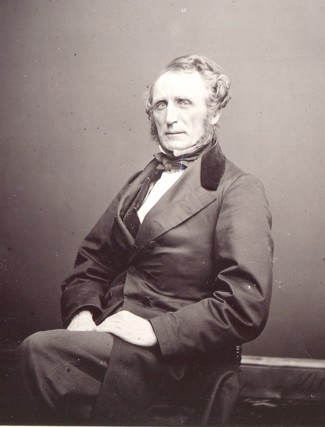

Several years ago, after driving past the impressively proportioned Harrison County Courthouse in my hometown of Cadiz for the hundredth time, I thought I ought to stop and look and in general confirm the identity of the man whose likeness is preserved in bronze, out on the courthouse lawn. “Ohio Congressman John A. Bingham”, a plaque read, and underneath, carved into pedestal stonework, there was this: “No more slave states, no more slave territories, the maintenance of freedom where freedom is, and the protection of American industry – Bingham at Philadelphia, 1848.” Ah, I’d had it right. I had heard about Bingham almost as regularly as I’d heard about Clark Gable, Cadiz’ other renowned native son, for folks in this area had been firm supporters of Union war efforts and Bingham was the hero who had prosecuted Lincoln’s assassins. As for the seemingly off-target explanatory text, even that made sense for it showcased how quickly and firmly Bingham showed the Radical Republican colors he was later to run up triumphantly while serving as Judge Advocate.

Upon getting home, though, I decided to do a little more research, and after confirming that Bingham was the guy who had delivered eastern Ohio’s rousing call to arms outside the Cadiz courthouse in response to Lincoln’s 1861 call for 75,000 troops, and noting as well that Bingham’s1855-1873 career in Congress coincided roughly with the second French Empire that bequeathed the architectural style used by the architects who designed the courthouse Bingham now adorns, I discovered that Bingham had also overseen the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, and, as if that was not enough, nominated both Edwin McMasters Stanton and George Armstrong Custer to their respective posts as Lincoln’s Secretary of War and Sheridan’s most prized cavalry officer. Amazing! Then came the stunner. Bingham had in addition drafted the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment? The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States?

As most readers already know, the Fourteenth is the second of the three so-called Renconstruction amendments that were enacted after the Civil War in an effort to protect newly emancipated, former slaves, and though the Thirteenth and Fifteenth were important in their own right (the Thirteenth prohibited slavery and the Fifteenth guaranteed a right to vote), the Fourteenth Amendment (enacted July 9,1868) had spectacular impact owing to the careful and deliberate way in which it extended to all citizens and indeed every individual on American soil “equal protection before the law”, a promise of “due process” should anybody run afoul of the law, and a strict prohibition against any abridgement of “privileges or immunities”. Lest anybody has doubt on this score, simply call to mind the still stirring tale of how the 101st Airborne deployed to protect the Little Rock Nine, after the 1954 Supreme Court decided against a Board of Education on the basis of 14th Amendment protection, and children were for that reason bravely planning to exercise their newly confirmed right to attend a customarily segregated Arkansas high school.

Yet that was not all the Fourteenth Amendment did via its crucial, Bingham-crafted Section One. Bingham’s phrasing also effected other things, most notably the transformation of our country from a federated republic in which power was evenly divided between states, on the one hand, and a national, so-called Federal authority on the other, to a more centralized polity whose chief feature has become an atomized, if universally enfranchised populace that increasingly looks to be fed and administered by a Leviathan state. Ever notice that the dome on our Capitol building, the Union cemeteries we bury our dead in, the greenback (“in God we trust”) currency we buy our bread with, our national sacramental meal (Thanksgiving, as instituted by Lincoln), and our most persuasive genesis narrative (the Gettysburg Address) all date from the 1860s? In part that’s because Lincoln was our greatest President and the Civil War tempered us a people, but the deeper reason for the above-mentioned coincidence is that the United States of America was founded anew during those years, and the legal means for accomplishing this founding was a Fourteenth Amendment that, designed as it was to rein in potentially racist state legislatures rather than potentially tyrannous concentrated power, altered the constitutionally embedded power balance between the states and the federal government so effectively that it practically outperformed Grant’s gunboats.

So: the Fourteenth Amendment is a rather important document.

Why, then, is its author not better known? When I discovered the identity of this author, it was a little like discovering Madison had once lived in one’s own back yard and the neighbors either hadn’t noticed or didn’t care. Why is that? Well, maybe it’s because John A. Bingham performed yet another service by crafting Fourteenth Amendment language in the way he did, which was to discretely liberate corporations as well as former slaves, the national government, and progressively minded jurists.

It’s a funny thing. I used to think of the river as the local sleight-of-hand province, for thanks to the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment (!) in 1919 and the ensuing prohibition of alcohol sales, bootlegging became big business in an upper Ohio valley that had already been established as a way station for the shipment of iron ore from the Great Lakes to Ohio river steel mills. At the same time, the Hanna-enabled, speakeasy-friendly “Ohio Gang” that had gotten Harding into office encouraged the city of Cleveland and neighboring upper Ohio River law enforcement agencies to grow rich by looking the other way. Thus conditions were well-nigh perfect in eastern Ohio for the establishment of illegal gaming and prostitution, let alone smuggling, and in Steubenville, a town which boasted a large proportion of miners and steelworkers with weekly paychecks to burn, gambling establishments and related amusements proliferated to such an extent that they became transformative. During the 1930s, gambling didn’t just occur, in Steubenville. Rather, it was part of the air everybody breathed. Sixth, seventh, and eighth grade students ran numbers across town for bookies like Pooch Lloyd or Money O’Brien as naturally as they delivered papers, if scholars had academic promise they didn’t so much think in terms of getting good grades as asking for a percentage of the action, and as for the young dice cheats or “mechanics” who evened betting chances behind the town’s multiple cigar store fronts, well, those Ohio Valley denizens went on to manage not-so-minor casinos like the Sands, out in Vegas, and the Tropicana, in Havana.

Lately, though, I’ve been revising this picture a little, for though the upper Ohio undoubtedly was a hustler’s paradise, it has become increasingly clear that the real sleight-of-hand action, the kind that results in the possibility of truly serious capital accumulation, probably occurred out in the dry town of Cadiz, where Bingham surely conceived some of his Fourteenth Amendment insertions.

Bingham’s professed intent, while drafting the 14th Amendment’s Section One in the way he did, was to fully emancipate black citizens by making sure (Madison himself had worried about this) that the Constitutional Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) applied to incursions by state power as well as federal power. In letters to friends crafted during the time he was working on amendment language, Bingham added that because “each person” was “created in the image of the Lord”, he considered it a solemn duty to protect their “inborn rights”. And – there is no reason to doubt the veracity of these statements. One of his best friends at Franklin College was black. Also, the historical record shows that no less an observer than Mrs. George Armstrong Custer (who spent a fair amount of time fighting off amorous advances while her husband was out west killing Native Americans) vouched repeatedly for Bingham’s character, even going so far as to say at one point that Bingham and House Speaker Schuyler Colfax were the “only exceptions to the rule of debauched bureaucrats and blackleg politicians” in all of Washington, and even if it were true that Bingham’s probity was perhaps a little less complete than Mrs. Custer thought it was, Bingham’s interest in justice appears to have been sincere.

However, there are other aspects to Bingham’s resume that give one pause.

For example, he never tempered his rather ordinary quasi-mystical bias in favor of “the Union” with caution or wit. Hence he was prone to sentimentality and acclimatized to the use of it, as a trick. “It is the high heaven of the 19th century,” he said during one speech delivered in 1858. “The bastilles and dungeons of tyrants, those graves of human liberty, are giving up their dead… [and] the mighty heart of the world stands still, awaiting the resurrection of the nations, and that final triumph of right, foretold in prophecy and invoked in song.” Second, Bingham habitually confirmed the rightness of things and actions by checking to see if they were “sacred” and “in conformity with the Divine Plan”. How did he know God’s intentions? Bingham didn’t worry overly much about that epistemological puzzle, for his wife, Amanda, claimed to have already solved it, and given that the couple lived in “perfect harmony”, why should Bingham second-guess his wife? Upon being asked to explain his decision to serve as prosecutor during impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson, Bingham simply reported that his wife had told him “the Sacred Union requires another Pilot for the Ship of State”. So, there are details like that one, on Bingham’s resume.

But the main reason to be wary is the sheer extent of Bingham’s ties to the still variegated, not yet monolithic, but increasingly formidable railroad industry.

When he was a lawyer in Cadiz, Bingham worked across the street from the Kilgore Building at Market and Main, where Daniel Kilgore (soon to serve as proxy for Thomas Scott, president of the soon to be massively powerful Pennsylvania Railroad) directed affairs for the Steubenville and Indiana Railroad. Hence Bingham was familiar with the railroad business, and when he got to Washington he regularly advocated for railroad companies, sometimes by sponsoring bills that extended iron duty credits, other times by helping to secure routes. The Camden & Amboy, Lake Superior & Mississippi, and Alabama & Florida railroads all gave him passes that allowed the congressman to ride for free. In 1857 Bingham bought land in Missouri in the hopes that it would triple in value once the transcontinental route under discussion in Congress was set, and during the Civil War proper Bingham both voted for the 1862 Pacific Railway Act, and opposed the formation of a special committee designed to investigate rumored links between railroad companies and government officials. After the war, Bingham gave a speech urging quick passage of the Northern Pacific Railway bill, and then, after accepting potentially valuable Credit Mobilier stock from former roommate Oakes Ames, who wanted congressmen to have a personal stake in the Union Pacific railroad company he was trying to grow — Oakes Ames was later charged with bribery, on account of this action — Bingham argued aggressively and consistently for the limitation of control by state governments over railroad companies. During a speech on the house floor in April 1869, Bingham reminded his audience that Congress had “$25,000,000 invested in these roads”, and then warned that “before next September” the money would be “substantially sacrificed by reason of the intervention of state tribunals which, if they had any decent regard for the rights of the American people, would not have interfered as they have.” The American people! Well, we shouldn’t be surprised. After all, it had only been a year since, with Credit Mobilier stock certificates satisfactorily banked and already generating extraordinarily handsome returns, Bingham had stood on the same floor and delivered similarly grandiose remarks at the end of the Andrew Johnson hearings. “None are above the law,” he at that point intoned. “Position, however high, patronage, however powerful, cannot be permitted to shelter crime to the peril of the Republic.”

Which gets us to the chief action to which Bingham was called, when he worked to secure the interests of RR companies – namely, liberating corporations from state control by inserting the word “person” into Fourteenth Amendment language, thereby qualifying naturally avaricious, potentially immortal wealth accumulation machines for the same protections freed slaves were soon to enjoy.

Prior to 1868, which was the year the 14th Amendment became law, state governments held corporations on a pretty tight leash. Perhaps because the memory of British East India Tea Company predation was still fresh, states granted corporations customized charters that could be revoked, should a corporation act in a way that proved injurious to a given community’s ability to govern itself. Yes, there was Union Pacific. And, yes, the liberation of modern corporations was already underway thanks to the hotly contested arrival of “limited liability” concepts, Pennsylvania Railroad president Thomas Scott’s invention of the holding company, and (a little further back) the Marshall Court’s 1819 decision in Dartmouth v. Woodward (which implicitly created a zone where private corporate charters were to some extent immune to the threat of revocation in a way that public charters weren’t). But the Union Pacific, created as it was almost by national behest, was clearly an exception, and even though regular corporations were becoming noticeably less accountable to the communities they operated in, they still had to apply to states for the “privilege” of doing business within any given state’s borders, and (assuming that they did business in more than one state) corporations also faced wildly varying degrees of taxation and regulation. Well, the 14th Amendment changed all that, and it did so by means of a single clause that prohibited states from discriminating between classes of “persons”, when imposing fees or taking property.

For those in the know, the word “person” had a definite pro-corporate charge at the exact same time that Bingham inserted it into the clause about “equal protection” (after carefully disentangling it from obviously human qualifiers like race, color, and birthplace). Railroad people knew there were advantages to be gained if “person” could get associated with the concept of equal protection before the law. Lincoln himself had used an argument based on the idea of corporate personhood as early as 1854 in an effort to secure protection for a railroad client against a trigger-happy county in the state of Illinois that had presumed to dictate taxation terms to that client, and though Lincoln lost that case, the impetus for defining railroads as juristic “persons” in order to gain the protection of local laws against non-uniform taxation only grew. By 1866, the year Bingham composed his draft, that impetus had the force of an oncoming locomotive. Hence it would have been surprising if someone had not tried to use the opportunity to lock in support for the personhood argument at the national level while hiding behind the cover of an altruistic concern for former slaves. Was Bingham, a railroad insider, that man? Or was Bingham, instead, a brave soul who risked public ridicule in order to insert “person”, rather than just “citizen”, and thereby protect illegal aliens as well as former slaves? So far the evidence suggests that Bingham was working for the railroads, for if you examine the 39th Congress’ Joint Committee of Fifteen meeting minutes (the log was published in 1907 by a group of Columbia University professors who themselves were studying the extent to which accumulated capital might have subverted democratic process) you see right away that Bingham consistently and steadfastly steered lawmakers away from drafts that exclusively linked proposed Fourteenth Amendment protections to “citizens”, and toward an April 21, 1866 draft that featured a second clause in which it was proposed that states also be barred both from “denying to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”, and too from “taking private property for public use without just compensation”. One week later, after notable vacillation, the committee conclusively adopted Bingham’s logic, and by June 8, while regular lawmakers on the floor were distracted by the question of whether to allow voting privileges to veterans who had fought for the Confederacy, the industry-friendly version cleared the Senate as well as the House.

A small matter?

At the time, it probably seemed that it was, given how precedent-setting Supreme Court opinions had almost all of them favored state control over corporations. In retrospect, though, that June 8 achievement looms large, for not only did corporations conclusively (in 1886) win the Fourteenth Amendment protection Bingham made possible and thereby win access to other protections customarily enjoyed by citizens like free speech (crucial for advertising) and immunity from unreasonable searches. In addition, they became able to capitalize on those advantages – and to a degree that nobody, perhaps least of all the Carnegies who ran the first vertically integrated corporations, could even have imagined, given that computerization and global free trade agreements did not yet exist. Welcome to the post-racial, federally managed American “marketplace” in which we live today – a world in which ordinary citizens like Tea Party advocates and Occupy Wall Street protesters have outsourced nearly every task requiring independence, bravery and sacrifice to all the better enjoy, courtesy of mutual fund dividend checks and take-outs from Chipotle, unparalleled access to safety, comfort, predictability, and ever-refreshed (corporately managed) desires that are most of them satisfied merely by watching multinational corporations do battle, freely, on a studiously leveled playing field.

Hats off, then, to Mr. Bingham who played arguably the most crucial part in founding this new republic. He deserves statues erected in his honor, and the rest of us should take heed to remember his name.

5 comments

CJ Wolfe

The drafting and intent of the 14th amendment is a REALLY complicated story (not disagreeing that Bingham had a big role in it). A good place to start trying to understand the drafting process is Raoul Berger’s “Government by Judiciary: The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment,” but even that leaves some things out

Rob G

Interesting — it looks a good bit like mountain-top removal mining, which I’ve seen the results of first-hand in southern W.V., although I realize it’s a stretch to call the hills around your environs “mountains.” Hopefully it won’t result in the same sort of long-term degradation.

By the way, it turns out we have a mutual friend, Richard Smith, who teaches at Franciscan. I had forwarded him the link to your other piece and he responded saying he knew you.

Will Hoyt

Thank you, Rob, for asking. No, the activity here isn’t pretty, but on the other hand it is fascinating and one of the things that most fascinates me is the sheer industrial muscle on view (thanks in part to the 14th Amendment) at the 22/151 interchange (and too just west of Cadiz and Scio), in the middle of stripped land or swamp that just two years ago was considered worthless. As you surmise, the game is oil/gas extraction. Horizontal drilling technology now makes it possible to fracture huge swaths of formerly inaccessible rock strata that lie one mile deep in the earth’s crust, then capture whatever carboniferous material gets released, and in one of history’s great ironies stripped-out Cadiz turns out to be sitting on the geographical center of a formation called the Utica that happens to have a lot of oil and so-called wet gas, in addition to regular natural gas. Hence oil companies like Hess and Gulfport have scrambled to join Chesapeake, the gas company, in their efforts to build a leasehold, and processing companies, surveyors, and pipe-liners have now arrived in their wake. Mineral rights that were formerly given away are now fought over, “land” now means an elevator shaft extending clear to the center of the earth rather than soil/trees/fields, and for those of us who live out in the country brightly lit drilling rigs that look like NASA launch towers now festoon ridges at nearly every point of the compass, come night. The billion dollar fractionation plants along 22 are being built by Mark West, whose corporate offices are in Colorado, and the similarly expensive rail-friendly plant west of Scio is being built by a partnership between 3M and EV Energy, which is based in Houston.

Rob G

Off subject, Will, but I just read your older piece on the mining in and around Cadiz. I’m from Pittsburgh and often drive US 22 on my way to Columbus, where I have relatives. What exactly is going on along 22W there as you drive up into the hills past Scio, etc.? It looks as if mining has begun again in force — or is that all related to fracking? Whatever it is, it’s not pretty.

Susan sklopfer

What a great piece of historical research. Fascinating and timely.

Comments are closed.