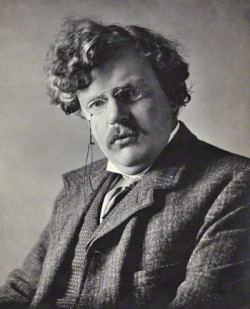

I once knew a woman who met Chesterton. It was a brief meeting in the 1920s when she was a girl of about ten or so. Her older sister invited her to go into London to hear the great man speak. Afterwards, her sister asked my friend, What did you think? She replied, “I think he looks like a big red lobster.”

Our mental images of Chesterton differ, certainly. And it’s a risible proposition, this article’s title, as though it were possible to capture such a character, oversized in several dimensions, in such a small space. As Dale Ahlquist once described him:

When he walks through the door, the first thing we notice is that he fills up the room. Of course, he weighs three hundred pounds, but his height is even more extraordinary than his weight. He is six foot four, but he seems even taller. He is a giant. But he is no Goliath. He is actually an overgrown elf. He casts a spell, and the spell is called joy. It is something we have certainly felt on some occasion, but this is something that sweeps into our souls. His huge body shakes with laughter. Laughter blows through his moustache. “I suppose I enjoy myself more than most other people,” he says, “because there’s such a lot of me having a good time.” (Common Sense 101)

Chesterton’s joy is no doubt part of the rationale for his cause for canonization, currently underway. (Saints, contrary to popular impression, are anything but dour figures.) Yet not so long ago, especially before the wonderful work of the American Chesterton Society in popularizing GKC’s ideas, his reputation had fallen into a slump, leaving him categorized as rather an old-fashioned sort of Catholic, too much the apologist, too hearty, too William Morris/pre-Raphaelite to be very interesting to us hip modern folk.

This “Toby jug” Chesterton is the one with which the late literary critic Hugh Kenner begins his consideration of the true greatness of GKC’s writings in his first book, Paradox in Chesterton, published by Sheed & Ward in 1947. The slightly dizzying introduction is by a friend of Kenner’s, the still youngish Marshall McLuhan, under whom Kenner had studied at the University of Toronto.

I mention the book because I find convincing its argument that Chesterton is “not so much great because of his published achievement as great because he is right,” as Kenner puts it. That is, he was not a poet but a metaphysical moralist whose special gift was his metaphysical intuition of being. And his special triumph was his exploitation of paradox to embody that intuition.

After all, Chesterton did not make paradoxes, Kenner argues, he saw them. He explored paradoxes as a means to truth, not through superficial playing but as “an intense plumbing among the mysterious roots of being and language.”

After all paradox is very much part of Christian tradition: think of the dying god, the child king and even the loving of one’s enemies. Chesterton did sometimes make puns merely for effect (although he liked to note that the Church itself is founded upon a pun: Tu es Petrus), he is usually paradoxical for a point. His goal is to liberate men from the strange predicament of both seeing and not seeing due to a kind of mental inertia. We have a need to see things anew, he believed, with a metaphysical art of wonder.

From such intuitions, it follows why GKC had such a love for small things—small countries, toy theaters, neighborhoods, etc. The world that is small, he said, can be full of friends.

For FPR readers, I will spend my remaining few hundred words on the essential GKC as a social theorist, a dimension in which his contribution to sanity is often skimped. And yet his prescience is remarkable.

“Most modern freedom,” he wrote in What’s Wrong with the World, “is at root fear. It is not so much that we are too bold to endure rules; it is rather that we are too timid to endure responsibilities.” He adds in another place, “The overwhelming mass of the English people at this moment are simply too poor to be domestic,” referring here to the lack of property ownership at the time.

And yet any opposition and rebellion we might mount to the current state of the world depend upon just these two things: property and liberty.

And what liberty did Chesterton claim? The freedom to restore, he would reply, especially to restore the oldest of ideals: the principle of domesticity, exemplified in the happy home, itself the one anarchist institution, older than the law and standing outside the State.

Threatening our homes is something called capitalism which should better be called proletarianism—a condition in which most people have wages because they don’t have capital. Chesterton saw all around him “this more enlightened England, in which the employee is living on a dole from the State and the employer on an overdraft at the Bank.”

The principle of property means, he argued, that every man should have something that he can shape in his own image, as he is shaped in the image of heaven. But no capital means no property.

When things go so wrong, as they did in GKC’s time and continue to do in ours, Chesterton said we need an unpractical man—a theorist, in fact. I think I know just the chap.

21 comments

Matt

Karen is right. Chesterton did not think women should work outside the home, and that they shouldn’t vote. She’s wrong about the motivation though. He believed this because he viewed working outside the home as inferior, a mark of desperate necessity perhaps but not something to strive for. Maybe he had some darker purpose deep down, but if so he showed no evidence of it in his writings.

Karen

Chesterton repeatedly argued that women should not hold paid jobs. At the time he was among this argument the overwhelming majority of paid jobs for women were in domestic service, and since he was middle class he would have benefitted from their work. Servants were poorly paid and had so few rights of recourse against their employers as to be virtual slaves. He never once wasted a single syllable stating that men should do their own damn laundry but blasted constantly against women having public jobs with good pay and contract protection. He knew or bloody should have known that many women worked and what jobs they had but obviously didn’t care. What mattered to him was preserving the sexual hierarchy where makes hold power over helpless females.

Wessexman

Your argument, Karen, seems, firstly, to be vague. What, except for slinging slanted, question begging insinuations – the sort that get current left-liberals all of a slaver – at him are you actually arguing?

You seem to think he was a hypocrite, but you don’t really nail down what you mean. You allude to maids, but apart from showing a great ignorance of Chesterton (who was not upper class but middle class in Britain parlance), but you don’t really show why he was a hypocrite in his views on women.

The rest is just the usual wild insinuations of committing a cardinal -ism, which politically correct left-liberals are so keen on.

D.W. Sabin

“non-feminist men”…oh…thats a rich one, I’m enjoying a streaming visualization of this completely contemporary phenom. Swift might have had a good crack at it.

Identity politics has us in a thrall of absolutist inanity that is continuing to atomize us as a culture..

There is a word in the English Dictionary : “misogyny” used to describe one who dislikes females. Funny how there is no countervailing term , aside from the dreadful “man” for a person who dislikes females. Perhaps it is because we groping troglodytes enjoy being bums . Hectoring notwithstanding

Karen

So, Rob G, what do you believe women should do? How will you enforce that?

Rob G

“You believe women are inferior but are too cowardly to say so. I expect you to be honest.”

Psychoanalyze much? And from a distance too! Just like the psychics on pay-per-view.

Karen

Because the views of women of non-feminist men are simplistic. You believe women are inferior but are too cowardly to say so. I expect you to be honest.

Rob G

“You insist on turning his views into a simplistic and unrecognizable caricature.”

No history with Karen, eh Mr. Crim? She turns the views of every non-feminist male into a simplistic and unrecognizable caricature.

Karen

He liked pretty pictures of domesticity from inside his own head; actual reality didn’t impinge on his daydreams. In the real world women are victims of brutes, usually their husbands or fathers. We need a way to escape which he would deny us in order to keep his precious “aesthetics.”

Karen

Rebecca West provides another example of a woman who saw through Chesterton.

Karen

You don’t get out much. Chesterton opposed women voting and working; I can’t see how has ANY women fans. Here is one example. Do you agree that women should be locked into their houses, without any economic or political power?

Elias Crim

I’ll try going out for short walks, then maybe down to the park and back.

“Do you agree that women should be locked into their houses, without any economic or political power?” No and GKC would not either. You insist on turning his views into a simplistic and unrecognizable caricature. His vision was not that of a dominating male: it was that of a lover of the creative potential in domesticity for all members of a family, i.e., an aesthetic vision. If you don’t get that, I’m afraid you don’t get Chesterton.

Karen

Chesterton was born in Kensington and attended St. Paul’s School, founded in 1509, hardly the schooling of a barrow boy. I can’t find any direct evidence of how much of a staff he employed, but it is extraordinarily unlikely that someone in his position didn’t have at least a cook and a couple of maids.

My argument is that he was a hypocrite. He decries women working in jobs that offered them a chance to get out of the house and earn more money and with a chance at promotion, but never wrote some much as a syllable arguing that men should do their own laundry.

Finally, if you think he had such a great view of women, why don’t you show me? Tell me why his nostalgic scribblings about women, unsupported by any actual evidence of how any women who lived anywhere but his own imagination lived are someone relevant?

Elias Crim

Chesterton arguing that men should do their own laundry: I think you got me there, especially as my knowledge of his work is not quite encyclopedic. I suspect he felt men’s obligations to women went quite a bit deeper than trading job descriptions.

I also wonder whether the club of women who hate Chesterton for his views on women must not be a fairly small one, as you are literally the only member I’ve ever come across. Either I need to get out of the house more or your objections are not well founded. His views on women are scattered throughout his writings but this collection would probably answer your demand for examples of his nostalgic scribblings that are also “relevant”:

http://www.amazon.com/Brave-New-Family-Chesterton-Children/dp/089870314X

Elias Crim

You are correct he and Frances were childless. Otherwise, your comments betray a perfect innocence of GKC’s personal life. He was not “upper class” and was an unrelenting critic of upper class views. If he employed someone to help Frances, then most observers would assume he did so out of consideration both for her and for the employee’s need for work. I think your idea that he had a false idea of how most women lived testifies to your indifference to his ideas generally. You obviously have other axes to grind, otherwise you could offer something here other than sneering (“his every single crude physical need”) and very fraught language.

Karen

In less fraught language, Chesterton had a completely false idea of how most women lived, and made no effort at all to learn. He cherished an ideal and when the ideal conflicted with reality, retreated into his fantasy.

Karen

Chesterton was a childless member of the English upper class who wrote dozens of pages about how dreadful it was for women to earn wages while having his every single crude physical need provided by an army of female domestic servants. So, it was terrible for women to work in offices and have their own incomes but perfectly wonderful for them to work for subsistence wages hauling water up multiple flights of stairs. Right.

Elias Crim

Karen, your rather crude description of GKC’s views on women is only contradicted by practically everything he ever did or said, beginning with his marriage to Frances. But perhaps you speak here as a one-percenter, someone whose economic privilege is partly based on women being liberated from the cook stoves in the homes, property their families once owned, in order to earn slave wages as doormats at Wal-Mart. Unlike yourself, apparently, GKC did not view this as progress for women.

Karen

And Chesterton decidedly meant HIS property, which included any Her who might reside nearby the male. His views on women — he wanted us to be cowardly, dimwitted doormats chained to cook stoves — should be enough in themselves to destroy his canonization but most Catholic clergy share his opinion of us.

Gromaticus

I can’t image being able to bear the company of anyone who thought that being “too William Morris/pre-Raphaelite” was a criticism.

Mark Gordon

Wonderful, compact essay on a figure whose prodigious output ages so well, better than even his close collaborator Belloc. Chesterton, like Augustine, is a man for our times.

Comments are closed.