Hillsdale, Michigan. I am a little late to the surge of 1s and 0s in response to Peter Conn’s less than tepid essay about faith and higher education. The gist of his gripe is the well-worn Voltairian notion that faith and reason are incompatible. Consequently, institutions like Wheaton College ipso facto cannot practice academic freedom because they require faculty and students to affirm certain doctrines (which it goes without saying cannot be questioned). Here’s an sample of Conn’s reasoning:

… unlike Harvard, Wheaton is one of the colleges that oblige their faculty members to complete faith statements. In other words, at Wheaton the primacy of reason has been abandoned by the deliberate and repeated choices of both its administration and its faculty.

Wheaton is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. When I asked a vice president at the association to justify the manifest disconnect between the bedrock principle of academic freedom and the governing regulations that corrupt academic freedom at Wheaton, he passed my question on to a person with the title “Process Administrator, Public Information.” The process administrator’s explanation, in full: “Federal regulations and commission policies require that the commission respect a wide range of institutional missions and belief systems in its accrediting processes.”

This, in my view, can only be described as a scandal. Providing accreditation to colleges like Wheaton makes a mockery of whatever academic and intellectual standards the process of accreditation is supposed to uphold. If accrediting agencies are playing by the rules in this continuing fiasco, then the rules have to be changed—or interpreted more aggressively, so that “respect” for “belief systems” does not entail approving the subversion of our core academic mission by this or that species of dogma. . . . Let me be clear. I have no particular objection to like-minded adherents of one or another religion banding together, calling their association a college, and charging students for the privilege of having their religious beliefs affirmed. However, I have a profound objection to legitimizing such an association through accreditation, and thereby conceding that the integrity of scholarship and teaching is merely negotiable. I also object to the expenditure of taxpayer dollars in support of religious ideology, in particular when that ideology has set itself in opposition to the findings of modern science.

Props to Conn for not pulling punches. So far, most defenders — Stanton L. Evans, Robert Tracy McKenzie, and Alan Jacobs, though there are others — have taken exception to the notion that Christian colleges restrict academic freedom. They counter that because institutions like Wheaton are the rare place where scholars can relate faith to academics, they are more liberal than secular institutions.

That rejoinder may only lead to a draw since the truth of Conn’s argument should be conceded by most believers. Christians may doubt and question the faith personally but if an institution — college or church — is going to stand for a certain body of truth, one that is beyond the power of reason (read virgin birth, immaculate conception, santity of Christians), it cannot tolerate those who question openly if not aggressively the faith once delivered. It seems to me a better response along the lines of dogma would be to point out how little the dogma of faith has restricted academic inquiry in the United States. Plenty of economic and political dogmas have constrained higher learning. Failure to support big business and world war — not a reluctance to affirm the Nicene Creed — was the primary reason for establishing the American Association of University Professors and for colleges and universities affirming its statement on academic freedom. Without going into the philosophical underpinnings of natural science, I doubt Conn would counter the notion that saying somethings on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus could get you in trouble (without tenure) such as admitting that you voted for George W. Bush or that you disagreed with Al Gore on global warming or gay marriage. But whether disliking Republicans or believing in climate change and homosexual rights rise to the level of dogma is another matter.

Either way, Conn should know that even the most irreligious of campuses in the United States are hardly sites where mental iron is always sharpening intellectual iron.

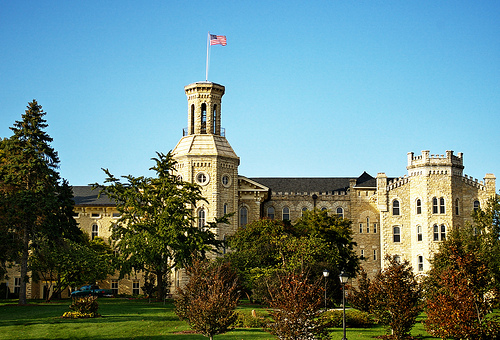

Another aspect of American higher education — arguably the most glaring — that Conn should know is the dirty little secret about accreditation. Harvard isn’t is, as I have learned but still maintain that accreditation has almost nothing to do with Harvard or the University of Pennsylvania’s academic reputation as I suspect Conn would concede. Since he compares Wheaton to Harvard on the matter, Conn’s invocation of accreditation must be almost as great a miscue as the accreditation process itself. As Jacobs observes, accreditors seek to uphold academic standards by examining student-faculty ratios, the financial health of the institution, terminal degrees of faculty, and even providing settings for disgruntled faculty and students to vent. Of late, accreditors have also pushed institutions to comply with certain social goods on sensitivity and diversity that can be an annoyance but seldom force an institution into activities that compromise mission. Accreditation is financially imperative for most schools — except institutions like Harvard that have almost as much money as the Institute for the Works of Religion. Without it, students cannot qualify for federally guaranteed loans and thereby enter adulthood in almost as much debt as you might incur by buying a home in Dupage County (the flat, leafy suburban home to Wheaton College).

The other part of the secret about accreditation is that it is the closest the United States comes to regulating higher education. To be sure, state legislatures approve charters to schools for the sake of granting degrees to graduates. This process involves a measure of governmental oversight, as does the federal component that comes with regional accrediting bodies that receive their powers from the feds. But compared to Europe — a part of the world that given his impersonation of Voltaire Conn may find appealing — the United States is chaotic, diverse, and antinomian. Institutions like your average liberal arts college — religious or not — don’t register in the world of European higher education because most — especially the best — universities are highly regulated and funded by European nation-states which have educational aims of training graduates for professions that will aid the nation. Conn might want to counter that Europe does have private universities operated by the Roman Catholic Church, a point that might help his case for the separation of faith and reason. But has he not been to Oxford, Cambridge, or Edinburgh where elite faculty funded by modern progressive governments (not having the slightest shred of Tea Party sentiments) have to work alongside faculties of theology? In point of fact, it is almost impossible to find a European university without a school of theology that trains ministers for the religious establishment. Is Conn willing to put Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh in the same category as Wheaton? What would he think if a Pennsylvania body of church and state officials determined who was going to acquire tenure in the University of Pennsylvania’s department of religious studies? If you think very long about the ideal university behind Conn’s argument, your mind runs more to Chinese or Turkish universities, which are secular in ways that Conn might approve but are hardly dogma free, than it does to European institutions.

Maybe the solution is to appoint professor Conn to serve a term of three years on Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools committee to oversee online and distance education programs. Or maybe the one on community colleges. If Conn thinks accreditation is all that valuable, let him experience it good and hard.

3 comments

John Gorentz

“institutions like Wheaton College ipso facto cannot practice academic freedom because they require faculty and students to affirm certain doctrines”

Uh, huh. Here’s another school (Waubonsee Community College) that demands conformity with certain doctrines.

Rutherford Insitute Files First Amendment Lawsuit against Illinois College

What does Peter Conn have to say about federally subsidized student loans for students who attend that one?

dghart

Ron, thank you for the correction.

I wonder if accreditation makes any difference to university’s reputation. Can you imagine anyone suspecting Harvard of an inferior education because unaccredited?

Ron

Accreditation

Harvard University is accredited by the Commission on Institutions of Higher Education (CIHE) of the New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC). Harvard, like all accredited universities and colleges, is reviewed for reaccreditation generally every 10 years and last received accreditation in 2009.

http://oir.harvard.edu/accreditation

Comments are closed.