Eastern Ohio

Jimmy the Greek, the odds-maker and point-spread pioneer who was born and raised and trained in Steubenville, the former (thirties-era) cigar store paradise thirty miles to my east, once observed that “crime has always struck me as notoriously disorganized”, adding that “if it were not, if there really was such a thing as organized crime, it would run the country”, and though Jimmy may not himself have been respectably credentialed in these matters, he did know a thing or two about the organizational prowess it must have taken to ensure that a gambling establishment remained solvent at the same time that it promised a level playing field to bettors. Moreover, he came surprisingly close in his ultimate assessment to the view of prestigious scholars like Karl Polanyi and Robert Nisbet who have speculated rather more systematically about the possibilities for collusion between government and so-called big business during the creation and enforcement of so-called free markets. Hence Jimmy’s quip has nearly always made me smile.

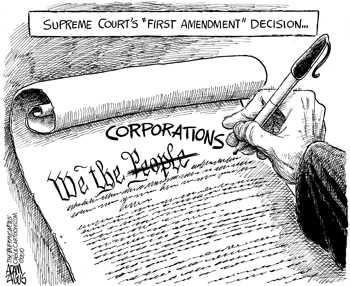

Lately though I’ve been smiling less quickly upon being reminded of his remark, and for the simple reason that other, sometimes much more famous people – for example Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton — have been implying the same things with a straight face this past fall on account of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision. Hillary said during the last televised presidential debate that the decision “permits dark, unaccountable money to come into our election system”, no doubt to second Bernie’s earlier, widely shared claim that the decision “essentially said” to “the wealthiest people” that Supreme Court justices were now “giving” to those same wealthy people “the opportunity to purchase the U.S. government, the White House, the U.S. Senate, the U.S. House, governor’s seats, legislatures, and state judicial branches as well.”

Let’s slow down, I want to say. Is it not obvious that the Citizens United decision is a lot more complicated, and perhaps less nefarious, than such comments suggest? Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission was a suit brought by a conservative non-profit linked to the Koch brothers which wanted to air a film that was critical of Hillary Clinton during the thirty days leading up to the 2008 Democratic primary. Airing that film during that time window would have been a clear violation of the 2002 McCain-Feingold Act whose intent was to minimize attempts by corporations to influence elections. Yet the Citizens United non-profit was emboldened by the FEC’s dismissal of their 2004 complaint about the airing of Michael Moore’s film, Fahrenheit 9/11, which explored links between the Bush administrations and Saudi Arabian leadership, the showing of which was not allowed less than thirty days before a primary (and sixty days before a national election). The court ruled 5-4 in Citizen United’s (and other, for-profit corporations’) favor. It explicitly rejected the argument that political “speech” by corporations should be treated differently under the First Amendment simply because (quoting from the decision itself here) “such associations are not natural persons”, and in that way provided an opening for the creation of Super-PACs, which have become vehicles for basically unlimited corporate spending on political causes.

A dark day for democracy? Justice Stevens said in his dissent that “democracy cannot function effectively when its constituent members believe laws are being bought and sold”, and it does seem now that it is harder to believe otherwise, given that profit-maximization machines which live forever and don’t have a conscience do, demonstrably, bring vastly greater leverage to bear than other corporations which aspire to work on behalf of the common good. Nevertheless the decision is not in all instances troublesome. One could argue, for example, that Fourth Amendment protection for corporations fighting hostile search-and-seizure actions is necessary, as well as reasonable. Also, there is merit to claiming, as the Citizens United majority did, that a corporation is an association of individuals who should not lose their claim to speak simply because they band together and speak as one. (Lest one has doubt on this latter score one has only to notice that businesses trying to resist ObamaCare contraceptive requirements are now better able to win lawsuits, thanks to the Citizens United decision.) And – last but not least – there is the need to respect carefully argued precedent and the ways in which corporations have evolved to obey that precedent.

Ought we not, then, to discount both the populist “read” on the Citizens United decision and too the unrealistic, if related, calls to discontinue corporate privileges based on personhood? Perhaps so, yet on the other hand perhaps not, for popular opinion can often be right when it uniformly runs counter to prevailing “expert” opinion; and, well, if history vindicated the public’s approval of The Sound of Music, it stands to reason it might also vindicate the public’s intuition that something was awry when the Supreme Court granted First Amendment privileges to the corporation called Citizen’s United. I for my part think such vindication probable. For the public has, in fact, been robbed.

What was indisputably stolen — the integrity of the electoral process? Not at all. The real thing the public has been robbed of is the chance to listen in as representatives deliberatively, exhaustively, and then conclusively weigh, in a public forum like a congressional hearing or even a Supreme Court case, the advantages and disadvantages of extending 14th Amendment protection to corporations in addition to citizens. People who’ve read the opinions in Citizens United will say at this point that Supreme Court justices were careful to cite precedent and in that way indicate how a conversation about advantages and disadvantages has (in effect) been underway for some time, and this is in a certain sense true. The Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision (2010) to recognize a First Amendment right to create Super-PACs aspiring to influence national campaigns stands on the Belotti v. First National Bank of Boston decision (1978) to recognize a First Amendment right to spend large sums of corporate money on state ballot initiatives, and the Belotti case, in turn, stands on Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific (1886) when its majority opinion reminds readers that “it has been settled for almost a century that corporations are persons within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

It would seem, in other words, that evidence indicating the wisdom of granting corporate protection on the basis of personhood status has accrued in the same way that evidence for First Amendment protection has accrued. But — it hasn’t so accrued. Instead, Fourteenth Amendment protection was established by fiat, and therein lies a tale. I have already written (in a different article) about how Ohio Congressman John A. Bingham, perhaps at the bidding of railway companies, inserted the word “person” (rather than “citizen”) into the second clause of the 14th Amendment’s Section One so as to make the “privileges and immunities” and “equal protection” detailed there available for use by corporations trying to protect themselves from hostile state governments, and not just recently freed slaves who were similarly trying to protect themselves from hostile state governments.

How, though, did corporations secure the use of the “equal protection” and “privileges and immunities” clauses once Bingham’s wording was inserted? Legal precedent allowing state control over corporations was not negligible, and for this reason convincing a court to accept a new argument that corporations should be granted protection as “persons” under wondrously powerful 14th Amendment language loomed as a challenge despite the obvious elegance of that new argument. Moreover, the climate of public opinion on such matters was not favorable. The only reason Bingham’s Section One passed muster in the first place was that the troublesome issues it raised were overshadowed by the seemingly more pressing issue of whether Section Three (which barred ex-Confederate soldiers from the right to vote) was too punitive; and if members of Congress had actually zeroed in on the implications of Bingham’s Section One wording in 1872 rather than 1866, Bingham’s Section One language almost certainly would have been scrapped, for the news about Credit Mobilier (the publically owned bank that had been manipulated by Union Pacific in its attempt to bribe Congress) scandalized most Americans and doubly convinced them that corporations should be kept on a tight leash.

Moreover, the Supreme Court at that point agreed. When slaughterhouses in New Orleans cited the 14th Amendment “privileges and immunities” clause in their 1873 suit against the state of Louisiana, after that state required the businesses to move their operations downstream from heavily populated areas, the Chase Court held that the 14th Amendment was designed to protect actual citizens, not corporations, and Justice Samuel F. Miller, who wrote the majority opinion, went out of his way to acknowledge the importance of the decision. Was it because he was the son a yeoman farmer? Whatever the reason, Miller virtually eliminated the possibility of ignoring or downplaying the problematic aspect to a “wide” interpretation of the 14th Amendment’s import: “No questions so far reaching and pervading in their consequences, so profoundly interesting to the people of this country, and so important in their bearing upon the relations of the United States and the several states to each other …have been before this court during the official life of any of its members.”

And then, in 1877, the Waite Court essentially followed suit in Munn v. Illinois by ruling that grain elevator companies and associated railroad companies could not, as “persons”, invoke the 14th Amendment’s “due process” clause in order to avoid having their rates fixed by state governments. “Down to the time of the 14th Amendment,” Waite wrote in his majority decision, “it was not supposed that statutes regulating the use, or even the price of use, of private property necessarily ‘deprived’ a man of his property without due process of law.” Thus it was becoming increasingly clear that corporate lawyers faced an uphill battle in their efforts to make use of Bingham’s slickly crafted first section. By the same token, however, it was also becoming increasingly clear that the ability of state governments and even counties to dictate terms to corporations was, from the point of view of corporate directors, intolerable. Thanks to Thomas Scott’s invention of the holding company, corporations like the Pennsylvania Railroad were now national in scope, and not surprisingly such corporations found it difficult to streamline operations when different communities exacted different demands. Additionally, the appearance of vertically integrated companies like Carnegie Steel meant that capital was being generated at exponential rates, thereby making possible yet more nationally oriented corporations with budgets that dwarfed those of most state governments. Hence pressure was building to take advantage of Bingham’s gift despite the wall erected to block that move.

The break came in early 1886, when a lawyer named Bancroft Davis pressed against a weak point in the now populist-branded defense. Davis was President of the Newburgh and New York Railway. In 1871 he had achieved some fame (the library I used to read in at Berkeley was named after him) by successfully arguing in Geneva that Britain should pay the United States $15,000,000 for damages inflicted by British-built Confederate warships, but now (1886) he was serving out a rather obscure appointment as Reporter for the United States Supreme Court. Hence it is natural to conclude that Davis knew what he was doing, when he inserted a line suggesting that the court knew corporations were persons into case history head-notes.

But, as with Bingham, we don’t know for sure. All we know is that the deed was done – that and the fact that the man who was serving as Chief Justice at the time, Morrison Waite, had been Davis’ boss during the 1871 Geneva negotiations. The occasion for the insertion was a twist in a suit that had been filed by the Californian county of Santa Clara against the Southern Pacific Railroad. When lawyers for the south San Francisco Bay county had stood up in the Supreme Court on January 27th to argue that Southern Pacific had no right to plead for the invalidation of target-specific county rules by invoking the now familiar personhood argument, they were cut off. “The court does not wish to have argument on the question whether the provision in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a state to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations,” Chief Justice Waite explained. “We are all of the opinion that it does.”

The Santa Clara team was caught off guard by this maneuver and to some extent frustrated, for they had built their case around a rebuttal of the personhood argument, but, knowing as they did that Waite’s remark carried no legal weight, they went home assuming that even if they lost the case, the fight about the legitimacy of a wide 14th Amendment interpretation was far from over. Well, Santa Clara County did lose that case – on a technicality regarding an improper assessment of fencing. When it came time to type up the synopsis in US Reports Volume 118, though, Court Reporter Davis didn’t mention the reason for the Santa Clara decision up front. Rather, he placed there a summary that highlighted Waite’s remark about the personhood argument. Right at the top, where cases are typically summed up in the briefest possible form, Waite wrote: “The defendant corporations are persons within the intent of the clause in Section One of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which” – and here he was simply quoting Waite – “forbids a state to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The reader isn’t told that this assertion had nothing whatsoever to do with the decision proper until the third paragraph, but by that point it is too late, for the second paragraph invites yawns and prospective readers are likely to turn the page and move on to the next case synopsis just in order to stay awake.

Now along comes Stephen Johnson Field, who grew up in a Congregationalist household in Stockbridge Massachusetts, the same town that Jonathan Edwards fled to after inciting the Great Awakening. Though renowned for approving a whipping post in a California Gold Rush municipality, inserting racist remarks about Chinese immigrants into U.S. Supreme Court opinions, and even carrying on a feud with a California Supreme Court justice that ended when a bodyguard employed by Field eventually shot and killed the California Supreme Court justice, Field’s real achievement had nothing to do with obviously provocative acts like these. Rather, it had to do with his willingness – indeed, his drive – to follow through on the work that had been so neatly and perhaps courageously begun by Bingham and then Davis. Back in 1869, while penning the majority opinion in Paul v. the State of Virginia, a case in which an insurance company claimed protection under the 14th Amendment in a dispute about fees, Justice Field had looked hard at the recently enacted amendment’s compatibility with the project of freeing corporations from control by the several states. Like Miller, he was scared by what he saw. “A grant of corporate existence,” he said, “is a grant of special privileges to the corporators, enabling them to act for certain designated purposes.” He added that “corporations, being mere creations of local law, can have no legal existence beyond the limits of sovereignty where they were created,” and he even expanded on this latter point, arguing that recognition of a corporation’s existence by other states “depends purely on the comity of those states – a comity which is never extended where the existence of the corporation or the exercise of its powers are prejudicial to their interests or repugnant to their policy.”

Sometime in the late 1870s, though, Field changed his tune. Was he alarmed by the sentiments driving the 1877 railroad strike in Pittsburgh? Perhaps he was just worn down (there is evidence for this) by the sheer volume of requests for 14th Amendment protection. Whatever the reason, Field recalculated his position on corporate use of the personhood argument. By 1885 (see Missouri Pacific Railway v. Holmes) he was implicitly affirming that the 14th Amendment applied to all classes of persons, and in 1888, after the Supreme Court had signaled a willingness to start deciding in favor of corporations rather than the communities they ostensibly served – see Wabash v. Illinois, in which it was held (reasonably) that states cannot regulate interstate commerce, and also Philadelphia Fire Association v. New York, in which Justice Harlan’s dissenting opinion approvingly reviewed the logic for recognizing corporations as persons protected by the 14th Amendment – Field referenced Marshall court nomenclature in a majority opinion and flatly declared (in Pembina Mining v. the State of Pennsylvania) that the 14th Amendment applied to corporations as well as human beings.

There: the stage was set. Would someone now be willing to follow through and “anchor” this opinion in precedent that did not really exist? Ten months later, on January 7, 1889, Field again obliged – this time while explaining the court’s decision in Minneapolis & St. Louis Railroad v. Beckwith, which upheld Iowa’s right to collect “double the value of stock killed” when a railroad company failed to install fencing. On the surface, this was simply another pro-state decision, but this time when Field explained the decision, he took a moment to stop and recognize legitimate portions of the railroad attorney’s argument. “It is contended by counsel, and we admit the soundness of his position, that corporations are persons within the meaning of the [14th Amendment] clause in question,” Field wrote. “It was so held in Santa Clara Co. v. Railroad Co, 118 US 394, 396, 6s.Sup. cf. Rep.1132, and the doctrine was re-asserted in [Pembina] Mining Co v. Pennsylvania, 125 US 181, 189, 8s.Sup. cf. Rep 737.”

To the angels in the wings, this must have been a freighted moment, and as for the rest of us – well, let us just say that the completion of Field’s last sentence still occasions a quick intake of breath. Like Bingham, Davis and Field did neat work! Thanks to their perhaps unwitting, nevertheless textbook-grade sleights of hand, one hundred years of precedent affirming the public’s right to oversee and if necessary shut down corporations was negated almost overnight. Rather than functioning as a country of competing people we were from there on out to function as a country of competing corporations; and, needless to say, corporations jumped at the chance to seize the laurel that had been handed them. Between 1890 and 1910, 94% of all cases involving 14th Amendment protection heard by the United States Supreme Court involved the consolidation, by corporations, of newfound gains, and once that flurry of legal activity was over and the only choice, vis-a-vis the maintenance of early 19th century wealth patterns, was either “progressive” redistribution or the facilitation of philanthropy, an entirely new front emerged where corporations slowly won the complete access to Bill of Rights freedoms currently on view in the Citizens United decision, on the basis of 14th Amendment access. Overall, the increase in corporate power resulting from Field’s 1889 decision was enormous, and, even more amazingly, that increase occurred without any public or judicial explanation of its merits. Indeed, the operation went so smoothly that, had they known about it, even Jimmy the Greek and other yet more skilled graduates of Steubenville’s school of dealing who went on to run casinos at The Sands and Caesar’s Palace would have been impressed.

14 comments

Rob G

Oh, come on, Art. For a perfect example all you have to do is dip into the voluminous back-and-forth about Wal*Mart that’s been going on for the past however-many years. Even floating the notion that Wal*Mart shows some of the traits of a monopsony evokes either howls of outrage from the usual suspects on the right, or cries of “And what’s wrong with that?” by the more libertarian, laissez faire sorts.

Rob G

There is, however, a certain cast of mind in some conservatives/libertarians that takes the view that a business that approaches a monopoly but doesn’t quite cross the line into actually being one is perfectly fine, irrespective of various suspect business practices. I imagine that this sort of thinking was what Weaver was responding to, as I’m sure he was well aware that there weren’t any actual monopolies, technically speaking.

“Private enterprise was not responsible for that.”

Not entirely, no. But there is certainly a tendency for very large businesses to have the skids greased for them by government, and to which lubrication said businesses do not often object. This is one manifestation of the loss of the “privacy” of property that Weaver was speaking of.

Art Deco

What ‘suspect business practices’?

In stating it this way, you’ve contrived an non-falsifiable assertion, ‘not quite crossing the line’ being undefined. If you look at the Fortune 100 firms of 1955, the largest firm in each sector had the following share (not of the total market, but of the Fortune 100 subset):

Aerospace: 20% (of 8 companies)

Appliances: 70% (of 3 companies – GE)

Chemicals: 36% (of 7 companies)

Controls & Switches: 55% (of 2 companies)

Copper: 34% (of 3 companies)

Food processing: 28% (of 12 companies)

Glass: 56% (of 2 companies)

Meatpacking: 58% (of 2 companies)

Metals: 42% (of 3 companies)

Vehicle parts: 61% (of 2 companies – Bendix)

Vehicles: 71% (of 5 companies – General Motors)

Office Equipment: 51% (of 2 companies)

Petroleum: 27% (of 17 companies)

Steel: 42% (of 7 companies)

Tire & Rubber: 42% (of 4 companies).

You do find industries with just one company in the Fortune 100 in 1955. The industries are: fabric, animal feed, HVAC systems, lead smelting, industrial machinery, packing material, paper, telephone service, photographic equipment, rail cars, sewing machines, and tobacco. You’ll indubitably find smaller companies competing in the realm of fabric, animal feed, industrial machinery, packing material, paper, and tobacco. AT & T was eventually dissolved through an anti-trust suit (and technological innovations).

Rob G

I was paraphrasing Weaver, who wrote in the 1940’s, not positing the existence of monopolies currently. Here is the direct quote: “Respecters of private property are really obligated to oppose much that is done today in the name of private enterprise, for corporate organization and monopoly are the very means whereby property is casting aside its privacy.”

Art Deco

The country’s economy was more dominated in 1948 by heavy industry which tends toward an oligopolistic market structure. That’s the main difference between then and now. Oligopolies are price makers, but they cannot grab consumer surplus in the manner of a true monopoly (and a Bertrand oligopoly cannot do so at all). However, there was also more vigorous enforcement of (somewhat ill-conceived) anti-trust norms at that time as well. When weaver was writing, monopoly was, again, limited to public utilities, mass transit systems, and, in may loci, railroads. Airlines operated under a federally administered cartel from 1938 to 1978. Private enterprise was not responsible for that.

While we’re at it, trade and industrial unions thrive by restricting labor market entry and exercising price-making power.

Robert M. Peters

I believe that Allen Tate wrote in “Who Owns America” that corporations were the stalking horses of socialism. While the legal owners of corporations are the stock holders, the effective owners are the boards and CEO’s. The legal owners of a socialist state are the people but the effective owners are the party cadre and elites.

The 14th amendment was not constitutionally ratified; and it effectively turned the Constitution on its head.

If is indeed an evil irony that a corporation is a “person” with all of the attendant rights, but the unborn are not.

Rob G

Right, Robert. That is what Weaver was getting at in Ideas Have Consequences when he talked about private enterprise losing its private aspect due to the rise of large corporations and monopolies.

Art Deco

Rob, the only ‘monopolies’ of any consequence are public utilities. They’re enmeshed in the political process because (1) they’re often state enterprises and (b) they’re subject to mercantile regulation when they’re not.

MARK MOORE

Corporations are not people. They are a legal fiction given whatever faux “life” they have by government edict. If you think corporations are people, why is it that we can own them? Corporations allow people to be shielded from the cost of some actions they might take which through the corporations, and also allows people increased power through collective action. Neither of these consequences, shielded from the costs of their mistakes or increased power, bring out any hidden virtue in men.

Corporations are useful, but I would rather attend to the difficulties of banning global corporations in America than face the difficulties they have brought us- artificial persons have more access to our political system than we do, and the global money that has funded both parties meant that both were relentlessly globalist no matter how nationalist, or better localist, the populations got. The blacklash to this failure and refusal to listen is President Donald J. Trump.

Nancy Bennett-Morgenstern

Aren’t unions groups of people speaking as one?

Art Deco

Unions function more as professional bureaux that groups of workers hire. It’s atypical there’s much internal competition within them. See historian David Witwer on this point.

While we’re at it, one can conceive of corporate speech as the shareholders speaking as one.

Peterk

You forget that Citizens United also applies to unions.

Brian

The fact is that the government was outright arguing for plain, simple, brutal censorship of political speech:

“CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: It’s a 500-page

book, and at the end it says, and so vote for X, the

government could ban that?

MR. STEWART: Well, if it says vote for X,

it would be express advocacy and it would be covered by

the pre-existing Federal Election Campaign Act

provision.”

The fact that this case is considered controversial, the fact that even a single Justice, even a single constitutional “scholar”, can think the government should have prevailed in this case, is a disgusting, disgraceful outrage.

Art Deco

It doesn’t seem to occur to the author that newspapers and publishing houses are seldom if ever proprietorships or partnerships.

Comments are closed.