Ingham County, MI

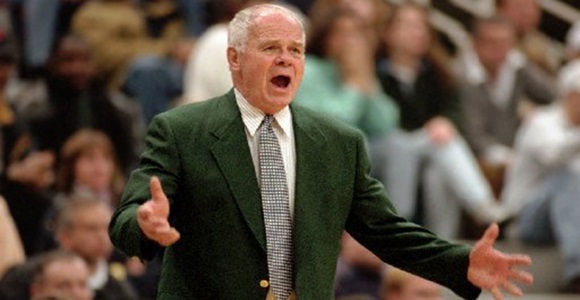

In the coming days the remembrances of Jud Heathcote, who died on Monday, will be many and various, as they should be, and they’ll come from more prominent and consequential people than I am or ever will be, as is fitting. But I too would like to say my piece, and so I’m going to.

I was in my twenties, lining up a putt on the third green at Forest Akers West—I mean the old third green, now the 16th—when I heard a burst of laughter coming from the 15th green (now the 1st). I looked up and saw Coach Heathcote walking toward the cup to retrieve his golf ball. He had just told a joke and, for emphasis, dropped a putt on top of it.

This was the man I knew only a little: the joke-teller who could really hold an audience captive. I would never forget that part of him, because it struck me, even when I was in my teens, as admirable—and, as I got older, useful.

At the time that he told that joke and sank that putt he might even have remembered me: the local two-time member of the Lansing State Journal Dream Team and the area’s leading scorer, the skinny undersized All-Stater who, notwithstanding these accolades, couldn’t begin to compete with a high schooler from Indiana for an offer from the program he most wanted to play for.

(That Hoosier was a pugnacious player named Scott Skiles. He and I once guarded each other in a pick-up game. I understood immediately why he was a Spartan and I was not.)

As a boy I attended Coach Heathcote’s summer camps and even managed, one year, to walk away with the camp MVP award. I was even more honored by one of Heathcote’s assistants, Bill Berry, who took me aside and said to me, “You’re a darn good player. But you’ve got to get out of that school.”

“That school” was the small private high school I went to, where my father was the superintendent and my mother the art teacher. There would be no getting out of it, obviously, and after high school, at 5’11” and 145 (most of us on the team also ran cross country and couldn’t gain a pound if you poured concrete over us), I played one year of NAIA ball. I had a great season but began to lose my desire—or, rather, to watch that desire transfer itself as if of its own accord from round ball to books. And that meant, at least for me, walking away somewhat reluctantly from the game that for so many years I had been obsessed with.

But although I quit the game earlier than I ever imagined I would—not counting noon-ball at the I.M. in grad school and all the noon ball after that until my knees forsook me—I never quit being Coach Heathcote’s student, even though he had long-since ceased being a coach. And that is the point, if patience permits, that I’m working toward in this little tribute.

I can remember thinking as a camper in Jenison Field House, listening to Coach Heathcote leaven his wisdom with humor, that he could easily be Johnny Carson’s successor. And he could have been. He was a talented public speaker and a great joke-teller. As much as I wanted to get out on that ridiculous rubber floor in the old barn and show him my stuff, I didn’t mind sitting there, cross-legged with the other campers, listening to his stories and jokes and advice. That’s how good he was.

One story concerned a player—one of his at Montana, if I remember correctly—who dropped dead in the middle of a game. I heard Coach tell the story several times, and it always included this sentence: “They put a sheet over him and carried him off the court.”

Some guys might have missed the Coach’s point, but I was pretty sure I hadn’t: basketball may be way up there on your list. It was way up on my list for a lot of years. But it doesn’t belong on the top of anyone’s list. Life is fragile. It’s more fragile than any ankle you’ve rolled ten times too many.

I had season tickets to Michigan State basketball for two years and two years only: the Magic Johnson years. My father, the superintendent, had also been a coach and, before that, a D-1 recruit. He wanted me to see this guy in action. I wore number eleven and was a Terry Donnelly fan, but on the way home from Jenison it was Magic my dad would ask me questions about.

“Did you see how he took the center lane on the fast-break right at the start of the second half?” “Did you see how he recognized the hot hand”—it might have been Vincent; it might have been Brkovich—“and kept feeding him the ball?”

Do you see how he knows where everyone is? Do you see how Magic makes those around him better?

His point was like what the catechism calls The Chief End of Man: you can drop a hundred percent of your shots, son, but a great player knows where the other nine guys are, all of them, all the time. He’ll make four of them look like hall-of-famers. The other five he’ll make look like spastics.

(“Spastics” was one of Coach Heathcote’s favorite words.)

I wish I had been a fly on the wall in 1979 to see and hear what went on in that storied meeting the players had with Coach Heathcote. They had lost their last conference game—to Wisconsin—and failed to win the Big Ten championship outright. And then, like Patton on his way to Messina, they simply tore through the NCAA tournament en route to a national championship. What had the players said to him in that meeting? How had Coach Heathcote responded?

I have a DVD of the championship game against Indiana State (there’s a case to be made for giving Donnelly a Second Most Valuable Player Award), but the climax of that run, for my money, was the Notre Dame game—right from the opening tip, which ended in the first of the game’s many dunks (go to 2:42). Next to Larry Bird’s Sycamores, the Irish—with Orlando Woolridge, Kelly Tripuka, Bill Laimbeer, and Bruce Flowers—were the closest anyone came to beating Coach Heathcote’s Spartans, and it was still a twelve-point win for the green & white. My dad’s college pal, Dick Enberg, did the play-by-play, just as he had earlier in the season when Michigan State dispensed of Kansas at Jenison.

You got the sense—I, at least, got the sense—that by the time the Spartans went on that post-season rampage, one of Coach Heathcote’s principles in particular had become second nature. He said it to me after a summer camp game. I had just hit a big man in the face with a pass, and Coach Heathcote, seeing that the guy was not the sort of player to catch a pass like that, said, “Peters, K.Y.P.”

Know Your Personnel.

The championship run looked to me, at age fifteen, like a perfect symbiosis of players and coaches knowing their personnel. There would be no repeat of the Wisconsin game or the skid Michigan State suffered early in the Big 10 season that year (four losses in a six-game stretch). There would be no getting in each other’s way.

If I’m wrong about this I would like to be corrected. I’d like Coach Izzo to call or write to me personally and set me straight. I would certainly take his word for it—especially if he throws in a couple of complementary tickets to the Michigan game. I watch Izzo carefully as he coaches. I’m a student of what little I can see of this game that has changed so much since I was a boy, and my respect for Coach Izzo is immense. His cager IQ is pretty impressive.

But even if he does call—and I mean no disrespect here—to me he’ll always be Coach Heathcote’s successor, his own obvious talent notwithstanding. And Coach Heathcote, though he had me under his tutelage for only a very short time, will always be way up there on my list of unofficial teachers.

For, once again, I’m in one of those basic freshman English classes, trying to teach writing to students who tell me they don’t like to read. I say to them:

“Does the name Jud Heathcote mean anything to you?” It doesn’t. Why should it? History is no more useful to young people than rhetoric.

“Jud Heathcote was the coach of the Michigan State Spartans when they won the NCAA basketball championship in 1979. A guy you might have heard of, a player named Magic Johnson, led that team. He had a running-mate named Greg Kelser. Kelser could snatch a dollar bill off the top of the backboard. Another teammate, Jay Vincent, Magic’s former high school rival, had the softest hands of any player you ever saw. Coach Heathcote never tired of making this observation. These guys beat Larry Bird’s undefeated Indiana State team on March 26, 1979.

“Well Coach Heathcote used to say to us at MSU’s summer basketball camp, ‘Boys, there are three ways you get better: by instruction, by competition, and by practice. I can give you some instruction, and I can provide you with some competition this week, but the practice you’ve got to do on your own.’”

The students don’t know where this is going, so I spell it out.

“I can give you some instruction on how to write, I tell them, “and you’ll get some competition from your classmates for sure. But it’s up to you to practice. You do that by writing, of course, but mostly you do it by reading.”

This is an example, I think, of how wide-ranging Coach Heathcote’s influence is and an indication that it’s going to go on and on and on for a long long time. He and I exchanged probably no more than a few a dozen words total, and that is all. I was a teenager at the time, after all, and he was a national championship coach, the legend I dreamed of getting chewed-out by as I ran over to the sidelines in old Jenison Field House. That part of the dream never came true, which the wisdom of time has taught me to be okay with. But I was one among many of this man’s lucky pupils, and his death, which we all knew would come, comes nevertheless as yet another pulverizing instance of loss in a life unrelentingly marked by loss. Loss is its defining feature, its salient feature, just as surely as it is the defining feature of the great game Coach Heathcote loved and gave himself to.

For most of us are losers most of the time. The fallings-off, the vanishings, never cease. The eyes grow dim; too soon the knees are bone-on-bone. Every year every team’s season ends in loss—every team save one, as we all learned, however fleetingly, on March 26, 1979.

Coach Heathcote knew as much. But he also could tell you how to deal with it, and the coping usually involved a good joke told well.

But they’ve put a sheet over him and carried him off the court.

5 comments

Bob Harris

This was perfect. Thank you.

MSU Ph.D. 1983. I was there too

Jeffrey Polet

You got the sense—I, at least, got the sense—that by the time the Spartans went on that post-season rampage one of Coach Heathcote’s principles in particular had become second nature. He said it to me after a summer camp game. I had just hit a big man in the face with a pass, and Coach Heathcote, seeing that the guy was not the sort of player to catch a pass like that, said, “Peters, K.Y.P.”

You expect us to believe this story? It asks us to believe you actually passed the ball, which was of course the point of your father’s grilling you after the game. “See what Magic Johnson did there son? He did something called ‘passing.’ You should try it sometime.”

Ted Bertrand

That was harsh but not entirely accurate I was in the room when his name was brought up and Jud said “Some school is going to get a poor man’s Terry Donnelly”

Justin

I passed this excellent piece along to my old man. He’ll certainly appreciate your sentiment, as I did.

I’m glad to see you back in action here at FPR, Dr. Peters. I’ve heard rumors of you writing several books. Any word you can share regarding the release dates of those?

Best to you and yours.

Ted Bertrand

I am a friend of Gene Washington I worked Security in Jenison in 78 and. 79 I visited Fletcher at the Federal Correctional facility in Ashland Kentucky in 2013 Juds greatest coaching job came in the form of 24 letters that saved a life I can share this with you. but the story is not for public consumption Bona fides Jud gave Fletcher the nickname Vacation for his practice habits Ted Bertrand class of 81

Comments are closed.