I was a bit surprised that Matt directed his critique at Twitter rather than at other forms of social media. At least Twitter isn’t as corrupt as Facebook and its opaque algorithms. (The private and well-moderated Wendell Berry group, which has over 6,000 participants, is a rare exception on the noise-amplification system known as Facebook.) Granted, claiming that Twitter isn’t as bad as Facebook isn’t really a ringing endorsement, and Twitter’s most notorious user continues to demonstrate all the ways that Twitter’s platform encourages people to use it for bad ends.

Matt is right that local life would almost certainly be improved if Twitter and Facebook didn’t exist. Facebook especially has monetized and fragmented our attention and our cultural conversations in frightening ways. But they do exist, and they have profoundly reshaped the publishing ecosystem, so those of us who want to think and write in public don’t get to do this in a social-media-free world. We can opt out or opt in, but we’re implicated in this ecosystem regardless of our choice. In many ways, this parallels the ways that cars have formed (or, rather, deformed) the North American landscape. You can choose not to own a car, but you still have to live in a world made for cars.

The question we face is how to foster healthy communities even while we’re dependent on systems that erode such communities.

Clearly Twitter and Facebook are globalist systems that are designed to draw our attention away from our physical places and communities. In this regard, Matt’s critique is spot on. Yet most of us are inevitable participants in many such systems. One of the most powerful images in Berry’s Port William fiction is that of Andy Catlett’s missing right hand, which was chewed by a mechanized corn-picker. For Andy, this lost hand represents “not only his continuing need for ways and devices to splice out his right arm, but also his and his country’s dependence upon the structure of industrial commodities and technologies that imposed itself upon, and contradicted in every way, the sustaining structures of the natural world and its human memberships.” As Andy’s missing hand reminds us, the question we face is how to foster healthy communities even while we’re dependent on systems that erode such communities.

Such dependence brings the temptation to simply capitulate and wholeheartedly adopt industrial methods. Andy, for instance, finds himself trying to defeat industrial farming at its own game. When he attends a large agricultural conference to speak on behalf of small farmers, he begins naming the friends and family members for whom he is speaking. Yet because he is speaking of them in this abstract, industrial venue, his efforts are for naught: “As he named them, the dead and the living, they departed from them.” It may very well be that when we try to talk about Wendell Berry on Twitter, the vitality of Berry’s vision will likewise depart.

But it is also possible, I think, that Twitter could be a marginal part of a well-lived local life. As Andy discovers, missing your right hand isn’t exactly an ideal way to carry on the work of farming. But that’s the situation Andy finds himself in, and he eventually finds ways to “splice out his right arm” with a prosthetic claw and carry on with the help of his family and neighbors. Trying to lead a faithfully rooted life in a global age isn’t easy, but we may be able to make do.

I’ve found Michel de Certeau helpful in understanding Berry’s approach to living well despite our complicity in unjust and destructive systems. Sometimes we do need to opt out of bad systems, but we should keep in mind that such systems may not be as totalizing as they seem. Certeau helps us see that we can find ways to creatively subvert bad systems, beating their swords into plowshares and making do along their margins. We can be like the fox who makes more tracks than necessary, some in the wrong direction. the New Pantagruel was exemplary in this regard, using wry humor to reveal the diseases of the “world wide web” from within. Might it even be that tweeting about Wendell Berry is rather like “singing hymns in the whorehouse,” to quote the New Pantagruel’s tagline? Localists who use Twitter or participate in the online writing “ecosphere”—including websites like FPR—had better find ways to go against the grain of these systems, to use them ways that redirect our attention and energy back to our places and communities.

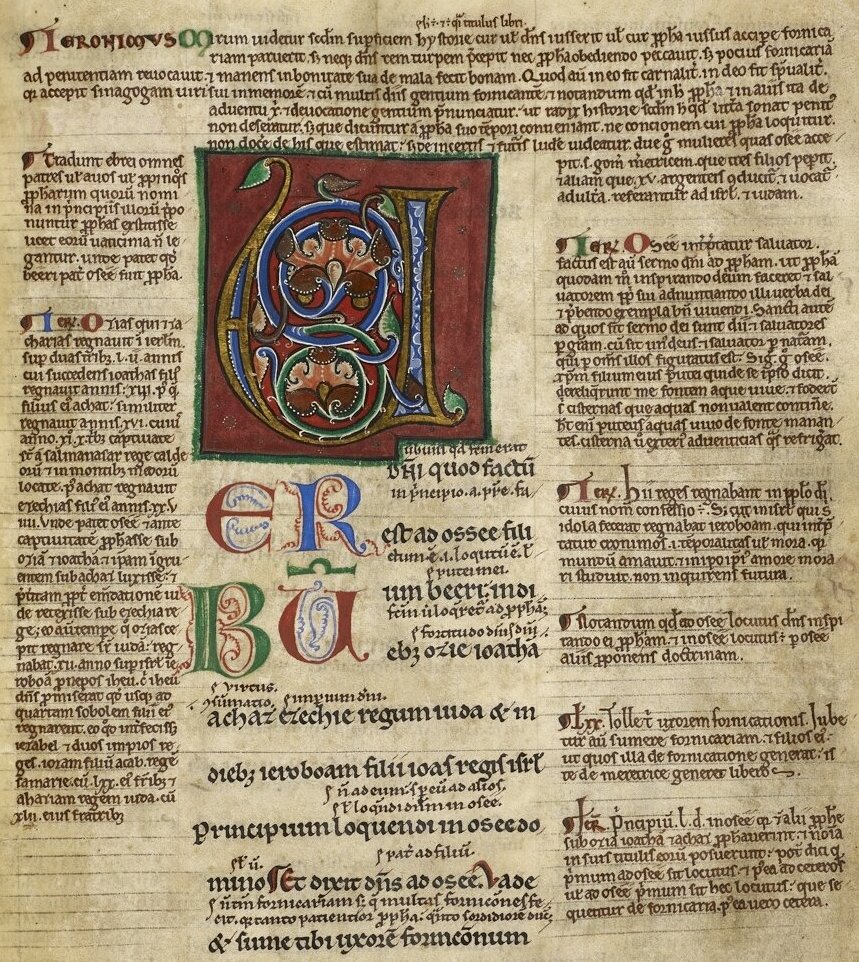

In keeping with these goals, I like to imagine Twitter as a contemporary space that is somewhat like the margins of medieval manuscripts. It’s a place for commentary, glosses, jokes, and conversation. It’s limited and circumscribed (the 280 character limit is rather like the spatial limits of a narrow margin). It often references other texts or sources. It’s not the primary text, but it provides a taste of how one’s broader community is responding to important ideas and received wisdom. Paradoxically, perhaps, Twitter can be a space that directs and focuses attention–rather like the manicules common in the margins of medieval manuscripts: “Read this. It’s important.” Of course, my analogy isn’t perfect. Twitter’s stream is relentlessly contemporary, overwhelming users with the tyranny of the present. Furthermore, most Twitter manicules point to things that aren’t worth attending to. So we should absolutely keep Twitter from become central to our reading, thinking, and living—when it becomes central, its noise and pollution drown out deep thought. But when it remains marginal, it can foster helpful conversations and help us make vital connections.

Here are some of the guidelines I’ve adopted to keep Twitter on the margins of my life and thought:

- Don’t own a smartphone.

- Use a Twitter app that eliminates all ads, minimizes photos, and has easy-to-use mute features. (If Twitter indeed takes away these apps, I’ll be leaving Twitter.)

- Follow guidelines like the ones that Andy Crouch lays out regarding time offline: “We are designed for a rhythm of work and rest. So one hour a day, one day a week, and one week a year, we turn off our devices and worship, feast, play, and rest together.”

- Don’t follow anyone who has “thought influencer,” “brand,” or “platform” in their bio.

- Post sparingly; the attention of others is a gift that should be honored and respected.

- Post about ideas and texts rather than trying to promote your personal brand.

- Twitter should be a tool for thinking with others. It shouldn’t be used to broadcast your life. My most significant joys and fears, hopes and loves never appear on my Twitter feed.

3 comments

Brian

“At least Twitter isn’t as corrupt as Facebook and its opaque algorithms.”

I don’t believe this is correct. Shadow-banning, as well as outright cancellation of accounts for no discernible reason, is a real thing that twitter absolutely wields against conservatives. And prominent conservative women seem to universally say that they just have to ignore harassment, even overt threats, because it becomes clear almost immediately that twitter just doesn’t care.

PS. Please note, absolutely none of that is meant to defend facebook. They’re both absolutely vile.

Russell Arben Fox

Jeff, I mostly agree with what I read here, just as I have generally liked and agreed with much of what this symposium has offered. But since I have a few minutes this morning, one question and one observation:

First, if you don’t have a smartphone–if you have, like me, an old flip cell phone which works just fine (until AT&T refuses to continue to support perfectly workable technology in favor of forcing me to make choices that would likely result in my become addicted to even more expensive technologies)–then what is the point of Twitter at all? Your very language (“Use a Twitter app”) doesn’t make sense outside of carrying around a damn internet connection in your pocket, does it? It doesn’t to me, but maybe I don’t even know what “app” means in this context. No wonder I can’t understand either my wife, my daughters, or my students.

Second, a limited defense of Facebook. Yes, it is an oppressive, invasive, relationship- and sense-of-temporality-warping technology, as was the telephone before it. I really don’t like FB–no one should, really–because its corporate policies have become so omnipresent and defining in how we use the technology in question (again, like Ma Bell in the past, though probably only 49-year-olds and older like myself will get that reference). But for people, like myself, that like to engage with others in argument over current events and ideas, FB, when properly cultivated and watched over, can sometimes–not always, but sometimes–allow for some genuinely interesting and enlightening conversations. I miss the hey-dey of blogs, where the notions of both responding thoughtfully and also responding in a timely way to ongoing internet conversations were, I think, balanced much better than they can be through FB. But as no one reads personal blogs anymore (even those of us who maintain them, to our shame!), other social media has to be put to work. Or so I think?

Jeffrey Bilbro

Russell,

Good points. “App” may have been the wrong word. I use TweetBot on my laptop, but maybe I should have called this a client or program? And like you, I’ll be a flip-phone user for as long as they continue making those things.

Second, I know FB can be a platform for conversations. I think private, moderated FB groups foster this the best. I absolutely agree with you that the blogging world was better, but FB, and to a lesser extent Twitter, has replaced much of that ecosystem. What bothers me about FB is its total dominance of social media, its obsession with gathering and monetizing personal data, and its opaque algorithms. I’ll have more to say about FB in a review I’m working on of Siva Vaidhyanathan’s Anti-Social Media.

Comments are closed.