Conservation is at the heart of conservatism. And the root of our contemporary ecological crisis is a careless, profligate mode of relating to the world; Francis Bacon would be proud of our current disposition as tormentors of nature. Conservatism’s stance toward the natural world, and the ecological crisis, sets it apart from the other philosophies and ideologies attempting to address this problem.

Roger Scruton has written and spoken eloquently about the essence of conservatism. Conservatism is not just the disposition of wanting to preserve, and build upon, an organic inheritance from one’s ancestors and pass this good constitutional and juridical order on to one’s progeny. It is also about conserving the spirit of humanism—the world of organic relationships and interpersonal relationships that constitute the Lebenswelt. It is the conservative outlook on ecology—and the conservative understanding of the relationship between self, the human community, and the rest of the natural world—which is the axiom for Edmund Burke’s statement: “the earth, the kind and equal mother of all, ought not to be monopolized to foster the pride and luxury of any men.”

Modern anthropology, along with the power and utopian promise of science and technology, contra Lynn White Jr., is really at the root of our ecological crisis. Francis Bacon, though a materialist and monist, bequeathed to the modern mind a functional dualism: man against nature. Moreover, it was not simply man against nature; it was man against a hostile and threatening nature. As Bacon made clear, man would have to strip and unclothe the natural world, pin nature down and violate her, in order to learn nature’s innermost secrets, which would then inaugurate the “reign [and] empire of man.”

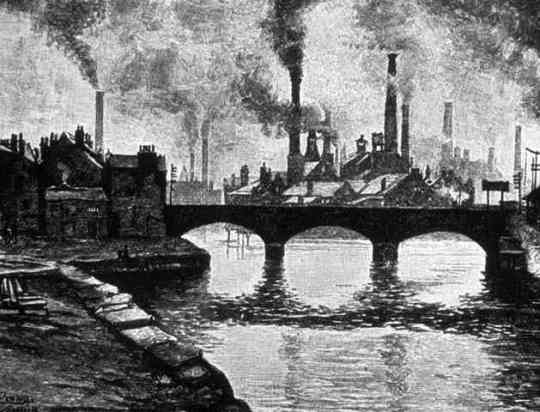

Bacon’s antagonistic anthropology isolated man from nature and set the two in opposition to each other. Furthermore, Bacon’s utilitarian philosophy furthered humanity’s libido dominandi. Although directed against the rest of creation, rather than other humans, the lust for domination exerted itself through the conquest and rape of nature. Those “dark Satanic mills” that William Blake speaks of, and the yearning to see Proteus rise from the sea as so poignantly captured by William Wordsworth, speaks to a more ancient Christian truth about the Fall of Man and the human condition which is relevant to our modern ecological crisis. Worse, Bacon’s philosophy established the world as pure object and humans as pure objects in a singularly objectified world. The end of relationship and subjectivity is what has followed.

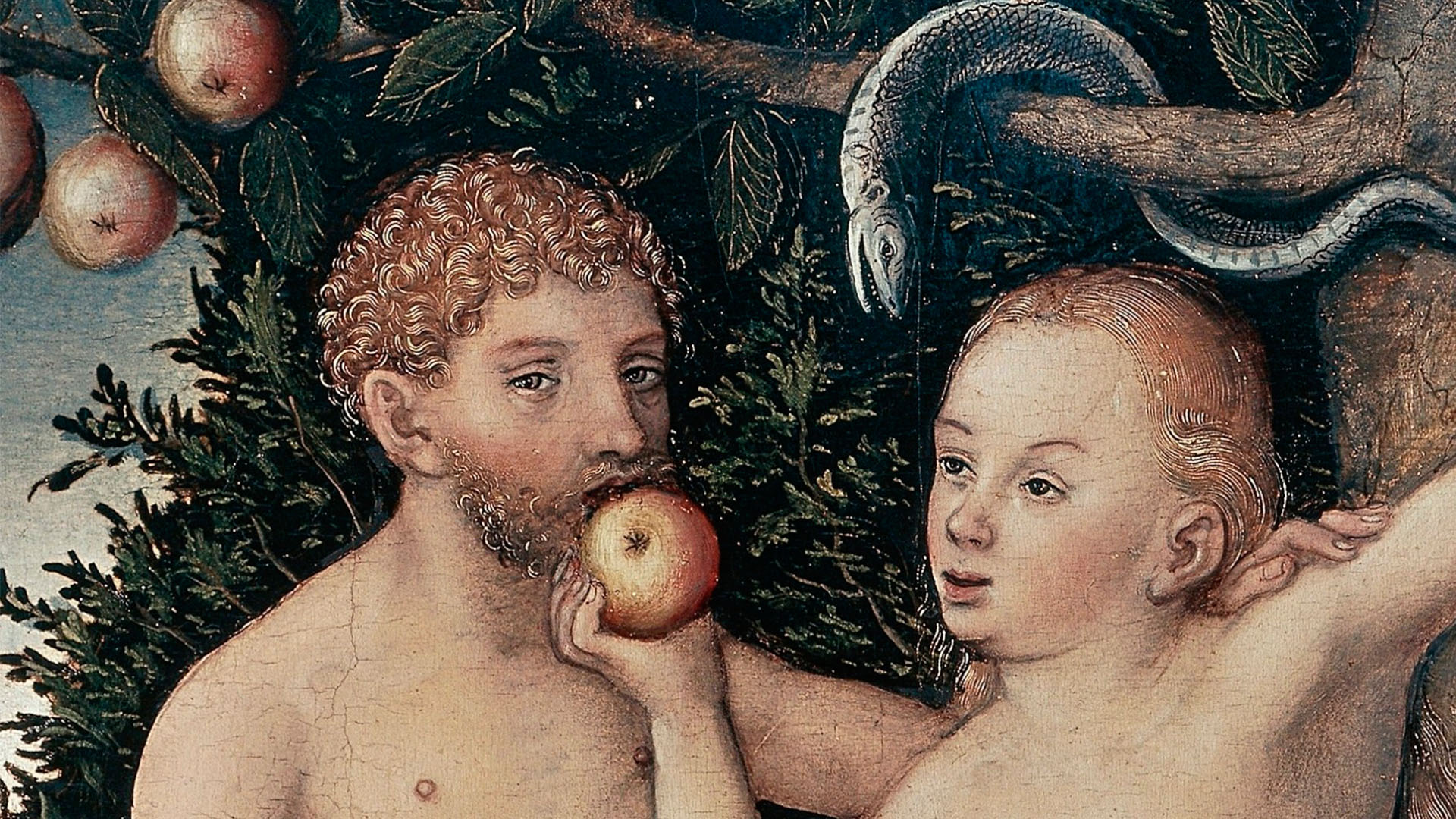

St. Augustine noted that the expulsion of Adam from the Garden represented man’s estrangement and alienation from the natural world. Man’s libido was not simply directed against other men, for Augustine, but also directed against the natural world at large. Adam may not have found fulfillment solely through relating with the natural world—for man’s social and relational nature required another human, Eve, to consummate it—but part of the Christian (and specifically Augustinian) disposition has always been that humanity is part of the organic web of intelligible nature. Man’s love of, and relationship to, the natural world is an important aspect of human nature and human flourishing, a love that calls us to be responsible stewards with what has been given. The ecological theologies of St. Francis and St. Bonaventure, two of Augustine’s most faithful disciples in the Middle Ages, do not make sense without the strong creationist and deeply Catholic anthropology which undergirds them. Humanity’s social nature moves us toward love of other persons, but our relational nature includes our relationship to the rest of the natural world.

Throughout history humans have relied upon nature to nurture us and provide a home in the world. It has only been since the twentieth century, and the second half of the twentieth century, that we have been able to imagine we are not dependent on the natural world for our livelihoods and well-being. Enclosed by mechanical monstrosities and reliant on metallic beetles for our commutes, the artificial structures of civilization—which have risen from Baconian (and modern) anthropology—have obscured our consciousness of organic relationships.

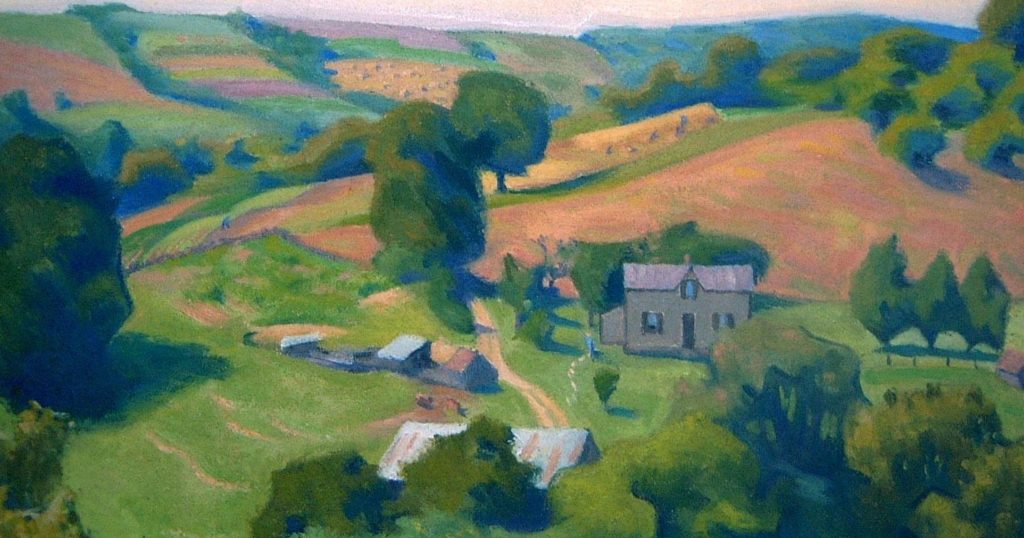

A vitalism and an organic understanding of the human person was, at least in part, rooted in an organic way of life. Toiling in the land and depending on beasts for survival, humans knew they needed a healthy relationship with sacred soil and life-giving and life-sustaining animals if their own lives, families, and communities were to endure. Those who depend on nature will often work to preserve it too. Attachment and rootedness equally contributed to an organic understanding of the self. Humans were part of nature, but humans were also distinct within (rather than apart from) nature.

This anthropology of vitalism and relationship, seen in Aristotelian and Catholic anthropology, stands over and against modern anthropology’s artificial character and functional dualism. We no longer see man as distinct within nature. Man is now distinct by being wholly separate from nature. Furthermore, man is not conceived of as an organic child of the earth, as the ancient creation myths from Babylon to the Bible had it, but as an artificially programmed machine—a “lumbering robot” in the words of Richard Dawkins—thrown into a hostile world who must conquer nature in order to fuel itself and survive.

The reduction of adam to a consuming object in a world of objects led the German romantics—beginning with Johann Hamann, but reaching a certain apogee with the likes of Johann Fichte and especially Friedrich Schelling—to try and resolve this metaphysical and ontological problem with energetic vigor. The I and Not-I distinction which characterized German dialectical philosophy from the late eighteenth through early nineteenth centuries, was primarily rooted in this crisis of the “stuffed dummy”—in the words of Hamann—lost in a sea of material objects. Part of the ecological and naturalistic pivot in Romanticism was a rebellion against reductionist objectification in materialist philosophy. It was an attempt to not only save human relationships with the earth, but also the integral vitalism of life itself.

Unfortunately, the best that the Romantics could offer was but another functional dualism wherein man was subject in a world of objects—still estranged and alienated through the geworfenheit (thrownness) of existence. Man would desperately seek attachment to and rootedness in nature but would fail in this endeavor precisely because he was not an object of worlding, but an alienated subject detached from the environment he found himself in. The Romantic mind was, as most have long maintained, a secularized iteration of Christianity’s fallen man. For, as mentioned, part of Christianity’s understanding of the Fall of Man was the estranged and ruptured relationship with the rest of creation that humans now experienced.

But this melodramatic portrait, this dialectical contrast between “Enlightenment” and “Romantic,” between modernity and counter-modernity, is just that—melodramatic. While the Romantics were keen to put their thumb down onto a critical issue, reading the Romantics would make it seem as if no human could possibly have a relationship with the natural world anymore. The proliferation of those dark Satanic mills, the complete uprooting of man from nature, and the restless and inevitable push to “progress” had utterly eviscerated the spirit of man. Artificiality and mechanistic life—nihilistic transhumanism—is the logical conclusion of modern mechanistic anthropology; this is what the romantics were passionately rebelling against. It is unsurprising that Romanticism culminated with Albert Camus and metaphysical rebellion.

Yet, this portrait of a universally estranged man is not what is found, or offered, in conservatism. To return to Scruton, part of the conservative ethos, from Cicero to Burke, has been the attempt to conserve this delicate relationship between man and world. Genuine conservatism seeks to preserve man’s relationship to the green garden he still finds himself part of. In fact, post-Burkean conservatism and romanticism in England was exceedingly ecological in orientation as described by Katey Castellano in her great study The Ecology of British Romantic Conservatism. Duties and obligations to progeny, the contract with the dead and not yet living, shaped the conservative mind and how it understood time, place, and land. The weight of conservative literature comes down decisively in favor of an ecological consciousness from the time of the Christian fathers up through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The difference between conservative ecology and contemporary environmentalism is in their competing anthropologies of constitutive relationship and objectified dualism. Modern environmentalism is still thoroughly modern in disposition. Environmentalism, as it is understood today, largely embraces the functionalism of Baconian philosophy. The natural world is an object which we do not have a reciprocating relationship with. We are not bound within the web of nature but exist separate from it—humans are objects capable of controlling (“saving”) the collection of randomized objects we call nature. The attempt to “save the environment” is an attempt to save a clump of objects which we have the power to save or destroy (one example of this is “Object Oriented Ontology,” which reduces humanity to the same plane of existence as other objects). This further objectification of man, ironically, is seen as the path of salvation while the traditional approach of man rooted in the world, with a home to cultivate, is seen as the poison which caused our ecological crisis.

Environmentalism situates itself thoroughly within the modern camp which has created the ecological crisis in the first place. The natural world is an object. We are objects. But we are the objects of control which permits us the possibility of “saving the environment” with other objects. Everything remains uprooted, depersonalized, and objectified.

Take, for example, the fact that most environmentalists live in urban areas that have obliterated the natural world to create an artificial environs. While it is true that it residents of urban centers are more likely to acknowledge the reality of global warming, there is a certain hypocrisy in holding signs to protest carbon emissions while living highly consumeristic lives. Such lives fuel the destruction of the Chinese countryside so as to allow these Greenpeace warriors to buy new smartphones, iPads, and cellular gadgets every six months. These people are living artificial lives, lives dominated by the artificial light of cellular screens which are the enactment of objectified living.

Meanwhile the people who express skepticism toward man-made global warming are more likely to live amid lush, rolling hills and forests teeming with wildlife. Whatever their fault in not acknowledging the ecological crisis that causes the urban Elect such consternation, the fact remains that many global warming deniers live lives reflective of the old human spirit. They live in and with the natural world. They have a relationship to the streams and hills that nourish them and have nourished their families for generations. And they live with a consciousness of respect for nature.

Conservatism’s ecological disposition rejects the functional dualism and utilitarian objectification of post-Baconian anthropology and philosophy. Conservatism’s ecology is one of relationships, vitalism, and a deep appreciation for the value of aesthetical appeals. As Scruton has argued, beauty entails responsibilities: “Beauty, order, and the home create demands.” It is a celebration of the human as human, the relationships that organic lifeforms build with one another, the relationships that humans—as biological and organic lifeforms—have with the rest of organic nature, and the relationships that humans have with their progeny in the way they preserve and pass on the place they call home. Conservatism is, and has always been, the philosophy of nature; it has always stood against mechanistic utilitarianism and the dangers of artificiality.

The destruction of the natural world is not merely the result of Bacon’s hostile dualism wherein man’s health and well-being come at the expense of nature. The destruction of the natural world is also the result of the loss of attachment to and rootedness in the land which we call home. Following Hobbes and Locke, who were faithful followers of Bacon, freedom entailed being unbounded from attachment and settlement—freedom was, as both Hobbes and Locke defined, unimpeded motion. Attachment and rootedness, of course, settle one into permanence and become a constrictive barrier which impedes free motion. Attachment and rootedness, then, are barriers to freedom.

The loss of such attachment and rootedness creates an irresponsible mentality and society. Why preserve what is ephemeral? Why preserve that which you are likely to leave in a few years? Why preserve that which you do not consider your home? Furthermore, why remain in relationship with an organic biome when you conceive yourself as a mechanistic entity, a lumbering robot programmed to follow selfish genes—the central computer—that is wholly separate from the rest of biological life?

Additionally, if life is just one fast-paced movement toward death, wherein consumption is the highest goal in life, then the conservative impetus to find and sustain a home is shunned. The environment then becomes an object of instrumental use for human consumeristic desires—just as Bacon had envisioned. The defaced and artificial landscapes of New York City and Los Angeles are centers of the equally defaced and hollow environmental movement which does not offer the real solution to our ecological crisis: attachment, settlement, and a more widespread ownership of land which necessarily follows from greater attachment and settled roots.

The modern environmental movement may appear as a reaction to the Baconian domination of nature, but it remains enmeshed in the techno-scientific mentality of mastery. The calls of environmentalists to “save the environment” or “save our planet” are nothing more than veiled language to allow for a new tidal wave of the libido dominandi to be unleashed in the guise of universal salvation, much like the dreams of Egypt, Babylon, or Assyria. Modern environmentalism still follows the same technological and scientistic method that has uprooted humanity and created our ecological crisis.

Love and care for the environment are only found in love and care for a home. Only a settled people, rather than a migratory people, only a people convinced of their longevity, perseverance, and life-giving destiny, can overcome our current ecological crisis. It is the migrant, vandal, and passerby, in contrast to the rooted and settled individual and community, who through lack of any attachment, and therefore lack of responsibility, destroys the local environments which they pass through. Care and responsibility require attachment, and attachment logically implies a relationship. In the words of Roger Scruton, “There is an internal relation here… We become answerable to other rational beings for our aesthetic choices.”

Our aesthetic choices are tied up with the ecological and humanist catastrophe of modernity. And I am not talking about the prospects of a global warming cataclysm—I am referring to the de-spiritualization and hollowing out of man by robbing him of a relationship with the natural world. By casting man from his garden, left now to wander endlessly and aimlessly (as a human right, mind you), making no demands of him in places he goes (because this would be a violation of his human rights, mind you), the economistic and materialistic worldview becomes perniciously widespread. Moreover, this exile and endless wandering is celebrated by modernity instead of mourned per the traditionalists. The migratory life is one of tragedy and darkness, yet our culture tends to celebrate its deracinated liberty as a part of “human rights.” Hence we recast our relationship to the world in purely instrumental and utilitarian terms without consideration of aesthetic, spiritual, or human concerns. The ecological crisis is a human crisis because it results from an anthropology that uproots humans from their proper place in creation.

From the nineteenth century to the present, conservatism has understood the slow-growing ecological crisis as a human crisis because humanity and nature are bound up with one another. This is not to reduce man to nature or animals, thereby destroying all sense of vitalistic distinctions between man and the rest of the world he finds himself in. But what conservatism understands is that the moral and spiritual health of man correlates with the vitality of the environment he finds himself in. The moral and spiritual degradation of man at present naturally leads to the environmental degradation that we see because of our intertwined relationship. As St. Paul says, “For the creation waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope thatthe creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God.”

In his epistle to the Romans, Paul lays out an essential Christian teaching—perhaps more in the past than the present—that the degradation and fall of man has ramifications for the rest of creation. If true than the converse is also true. The sanctification and beautification of man also leads to the sanctification and beautification of creation. Man’s redemption is also creation’s redemption. This is what the Church Fathers, especially St. Maximus the Confessor, understood by “cosmic redemption.”

The conservative view of our ecological problem rests on fundamental conservative dispositions concerning man’s nature: That he is a social and relational animal first and foremost, and this extends also the environment which he finds himself living in; that man is a loving creature with an appreciation and desire for beauty; and that man is a subject-being distinct (but not apart) within the web of nature. Man is not, therefore, a lumbering robot, an object programmed by selfish genes as a ball of matter in motion until death. Further, contra both the economistic left and the economistic right, man is not meant to live as an object detached and separated from the world.

The conservative knows this deep truth about our ecological crisis: It is the result of a lack of attachment, a lack of settlement, a lack of appreciation for beauty, and the attempt to remodel adam as an animalistic consumer rather than a tender and tiller of the garden God has provided. Our moral and spiritual health is bound up with the world we reside in. As our morals have waned, our drive to consumerism advanced, the objectification of the world and ourselves sped up, and the emancipatory dream of remaking the world in our image has infected our mind, the environment is also spiraling with us to destruction. Moral and spiritual regeneration, and greater attachment and relationships to the land we call home, are the first steps to resolving our ecological crisis.

5 comments

Dan Grubbs

An insightful read. A lot to chew on. I certainly could hear echos of Berry here — and to this observer, that’s a very good thing.

Grant

Mr. Krause,

Edifying article, thank you! I wish my fellow “conservatives” had such a rich, organic understanding of conservatism!

Rob G

While I agree with most of what is being said here, it should be pointed out that the Burkean strain of American conservatism has largely been marginalized by the ascendancy of neo-conservatism and its libertarian-leaning economics. Mainstream conservatism would take some convincing, as it’s mostly forgotten its Burke/Kirk heritage, alas.

Senhorbotero

Wow. I have only recently begun reading here and this is brilliant. Excellent write up. I think even beyond the ecological troubles you put your fimger on the whole problem with the West really. Thanks for taking the time to put this together.

Aaron

“Environmentalism situates itself thoroughly within the modern camp which has created the ecological crisis in the first place. The natural world is an object. We are objects. But we are the objects of control which permits us the possibility of “saving the environment” with other objects. Everything remains uprooted, depersonalized, and objectified.”

Those of us who live in the mountain states deal with the practical results of this view all the time. It pits the people who actually live here, against those who want to turn it into some sort of controlled park, under glass, on the other side of the velvet rope.

Comments are closed.