In selecting reading material, the average reader might not immediately reach for a book about Congress in the nineteenth century. That would be a mistake, as Joanne Freeman’s book The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War is an historical highlight from the past year. With clear, active, and occasionally very funny prose, Freeman draws the reader into both the individual stories of each chapter and a broader story of political violence.

Freeman (Yale) has been thinking about political violence for a long time. This book continues a story she began in Affairs of Honor (2001), a book about violence in the very new nation. This story starts in the 1830s and winds its way up to the Civil War.

Although Freeman doesn’t divide up the book’s flow, I sensed three movements in the book.

The first is a general depiction of how Congress operated in the antebellum period. Looking back at the period, even historians are apt to valorize its functioning. It was, after all, the stage on which walked “the god-like Daniel” Webster of Massachusetts, whether he was responding to anti-unionist sentiment of Robert Hayne of South Carolina or arguing for more mundane matters. The halls also witnessed the orations of Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. For an age of popular oratory, Congress could not be matched. Freeman, however, reveals the very human and basic side of this democratic institution. Senators and Representatives were operating in very close physical spaces, in rooms with poor ventilation. Nerves frayed as sessions stretched deep into the night. Spirits were raised (or lowered) as Congressmen consumed a variety of spirituous beverages, with several locations throughout the Capitol providing copious amounts of liquor. Against this backdrop, an honor culture suffused the masculine setting, and insults that crossed the line from political to personal could lead to demands for satisfaction.

Our guide into the labyrinthine maze of personal and political interactions is Benjamin Brown French. French arrives in Washington from New Hampshire in the early 1830s. He will obtain a clerkship in the House, eventually becoming House Clerk, before losing his job in a switch of partisan control. He also kept an extensive diary, which Freeman mines effectively. He is one of the main windows for understanding the dynamics of Congress. His life also effectively tracks political developments in the North. He came from New Hampshire as a committed Jacksonian Democrat who counted Franklin Pierce as one of his friends. Seeing pro-Southern antics up close, however, pushed him into the role of first a Free-Soiler and then a Republican.

The second movement tracks the period of the 1830s and 1840s. During this period, limited violence occurred with regularity. In a well-drawn chapter, Freeman describes the only Congressional duel to end in a fatality. Largely through misunderstandings, Jonathan Cilley (a Democrat from Maine) faced William Graves (a Whig from Kentucky), and Cilley was killed after several exchanges of fire.

Also in this period, Congress wrestled with the gag rule—the Congressional policy that silenced anti-slavery petitions. Here, John Quincy Adams (back in the House after his presidency) shines heroically. Adams had the stature to avoid duels and to brush off southern bluster. At the same time, he was a master of procedure, and he used every trick he could conjure to evade the gag rule. After nine years of fighting it, Adams succeeded in defeating the rule in 1844.

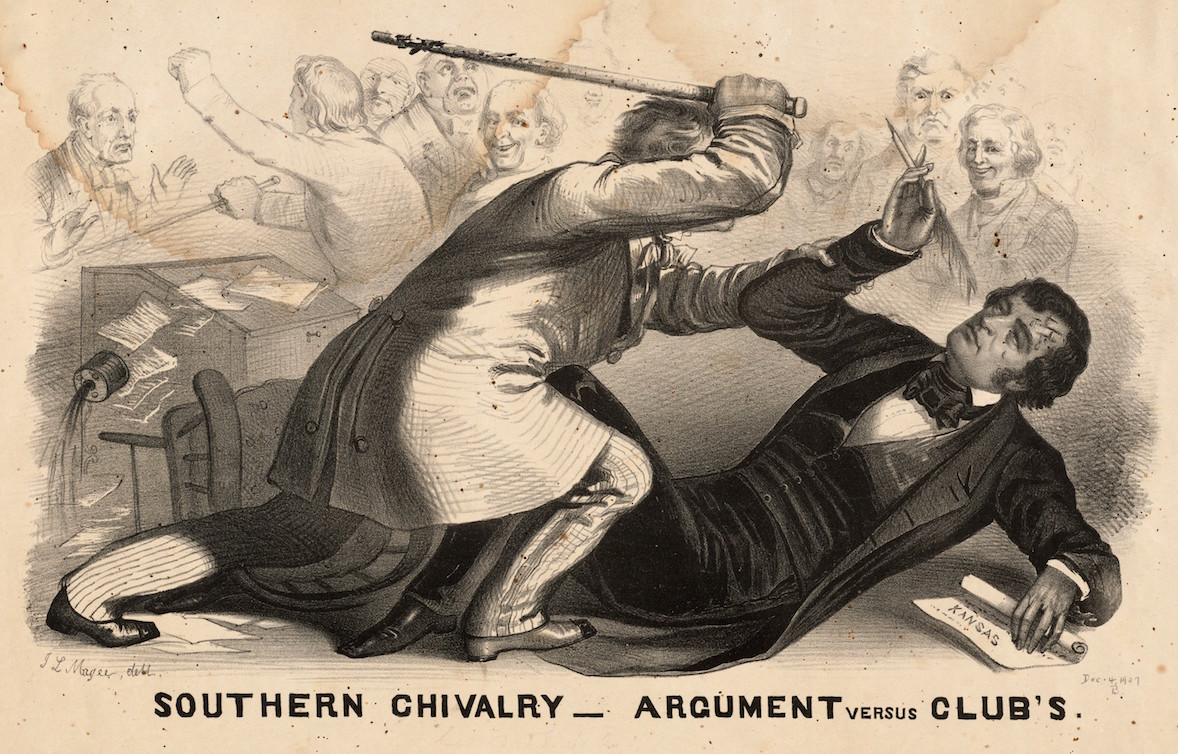

Shortly after the gag rule repeal, the country entered the Mexican War. The third movement examines how the debates over slavery went into overdrive after the War and the acquisition of new territory. Escalating rhetoric of violence and practices of personal violence laid the groundwork for national violence to come. In this period, a new Republican party emerged that so strongly opposed slavery it was willing to fight, to match proclamations of bravado. In refusing to be cowed by southern threats, northern Republicans demonstrated their unwillingness to yield. New anti-slavery Congressmen like Joshua Giddings, Galusha Grow, and John “Bowie Knife” Potter refused to buckle under threats and so returned violence for violence. The smaller incidents of violence of the 1850s set the stage for the most well-known single act of violence, the caning of abolitionist Charles Sumner by South Carolina’s Preston Brooks. In this section, Freeman demonstrates the escalating animosity between sections that eventually produced the splintering of the Union and the Civil War.

Freeman’s book succeeds in helping readers understand the reality—the often gritty reality—of national politics in this era in a way that is both narrative and analytical. The story moves along, deeply researched but communicating extremely well.

At the same time, readers may ask about the organizing category of violence. And, it’s true that much violence was occurring. Simply bringing all actions by all sides under the umbrella of violence, though, doesn’t distinguish what the violence was about or if either side was justified in its violence. Taking a page from the discussion of just war theory we might ask if there was a difference between offensive and defensive violence. Likewise, should anti-slavery northerners have merely allowed southern threats to dissuade them for pursuing their opposition to slavery? From both their day and ours, there was virtue in demonstrating courage against oppression.

Finally, it is worth considering how this history might have relevance for our day. Freeman makes her claim clear up front. In an Author’s Note before the text, she lays out a direct connection between violent language and political breakdown. She decries violence of language as leading to actual violence. Extreme polarization is a threat not only to congressional functioning but to national unity.

These concerns, expressed sincerely, deserve attention. We should recognize the reality of polarization. There is the danger that even thoughtless words will sow the wind but reap the whirlwind. There is thus much to recommend respect and decency for leaders to reach across the aisle, when agreement can be achieved. This is one burden of recent books by both Senator Ben Sasse and Arthur Brooks.

But, such bipartisanship should not detract attention from the very real differences that divide Americans—often rooted in competing metaphysical, moral, and spiritual commitments. Given these divides, we might wonder if Congress is the best place to consider such matters. On the one hand, real deliberation should be welcomed, and legislation through collaboration will produce greater popular assent than unilateral actions of either executive orders or court diktats. Many Americans would welcome a Congress that conducted business according to regular order and adequately accomplished it basic functions.

If possible, important and contentious debates should be sent back to the states and even to counties and communities.

At the same time, wouldn’t it be better still to address matters of great dispute through a system of federalism? Some issues are indeed national and deserve a national policy—but not all are. If possible, important and contentious debates should be sent back to the states and even to counties and communities. This would force neighbors to reason with one another and together frame the moral lineaments of their shared lives.

Empowering more Americans to make decisions relating to their own experiences will actually nurture robust citizenship. Through practice, more individuals can learn that responding to challenges with humility, grace, soft words, and solid arguments are all virtues to be cultivated. Joanne Freeman reminds us of what can happen when political passions burst their bounds. To avoid the worst, it’s worth examining the best in America’s political traditions again.

2 comments

Brian

“Escalating rhetoric of violence and practices of personal violence laid the groundwork for national violence to come.”

I don’t believe this. I think this is the same misguided notion has some people today saying that Americans would be happy and content with their lot if politicians (those from the other side, of course) just talked and behaved better and didn’t stir things up.

“In this period, a new Republican party emerged that so strongly opposed slavery it was willing to fight”

I don’t think this is correct either. Those who wanted to fight thought the Republicans were weak sellouts, no?

[A final comment not in direct response to anything in this article, but I think there is a colossal mistake being made by governments, parties, and media/tech companies, accelerating since November 2016, to attempt to suppress offensive and/or dissenting voices. Nothing boosts radicals who want violence like the demonstration that their movement is being suppressed and they can’t be heard through non-violent means.]

Brian Villanueva

There is a grave difference between the Congressional violence of the 1800’s and what we see today. 1800’s Congressional violence (mostly) was cause by, as this article says, passionate men in confined, uncomfortable spaces with fraying tempers. I would call that frustration violence and it is described well in this article.

Today’s political violence is not confined to passionate representatives who are thrown together to solve intractable problems. Our radicals (whether Anti-fa, Operation Rescue, or a of the mill millennial college student mob) seek out their enemies to target. They aren’t thrown together and violence happens; they seek violence out. This is especially odd since Putnam and others have consistently found we are segregating ourselves away from those whom we disagree with. In short, we separating from our political enemies, but at the same time, some of us are seeking them out for the express purpose of hurting them.

That’s not frustration violence. That’s war.

Comments are closed.