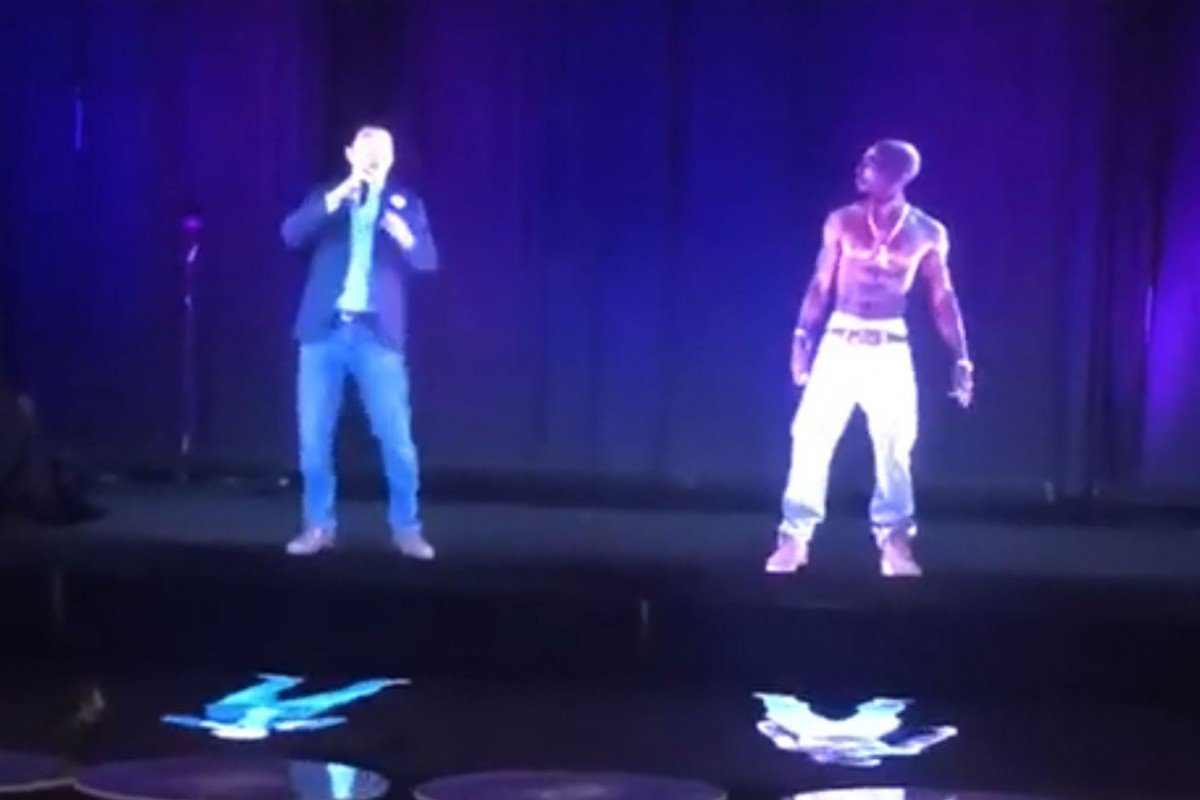

Presidential hopeful Andrew Yang is trying to make waves by taking a cue from Coachella. In 2012, a hologram of the deceased rapper Tupac famously performed at the music festival. So, in 2019, Yang has purchased three holograms of himself he plans to use in his presidential campaign. He announced this development by having his hologram perform with the Tupac hologram. But according to the Fugees song “Zealots” from their album The Score—released the same year that Tupac died—“two MCs can’t occupy the same space at the same time. It’s against the laws of physics.” Holograms may seem to bend the laws of physics, letting Tupac and Yang be in the same place at the same time and letting Yang be in four places at once. But Lauryn Hill was right in her verse on the song: if we don’t heed the natural universe, we’ll “weep as your sweet dreams break up like Eurythmics.” Being in four places at once is not only impossible, it’s undesirable.

The most recent cover of Harvard Business Review promises insights into The Age of Continuous Connection. While some, like HBR, think this is a business opportunity to master and exploit, others realize it means that some employees never really experience being off the clock. Smartphones, especially, have made employees increasingly responsible for after work emails, so that they don’t disconnect late at night or over the weekend. Many people are never really away from work. Andrew Yang is not the only person who would seem able to benefit from a hologram. At least some people are recognizing that these increasing demands on our time and presence are unhealthy. While the government considers modifying the white collar exemptions for overtime pay, others turn their attention to children. There is an increasing amount of concern and debate in our culture about overscheduled kids. It’s not just adults who have a growing list of commitments and places to be.

Despite the demands on our time, humans come with built-in geographical limitations. In the nineteenth century, doctors worried about the effects of locomotive speeds on our organs, and no one thought that the four-minute mile could be broken. We broke the four-minute mile, and we fly faster than trains without medical harm, but we still can’t be in any more places at once than those nineteenth-century doctors could. Even our minds can only comprehend so much of the world at once. Neil Postman’s work on information overload reminds us that we can’t process all of the news we receive from the media, especially about places far away. We become overwhelmed when we try to go everywhere at once, either physically or mentally.

The demands we feel and our desires to be everywhere at once can make us think that life is just too short. But around 49 AD, the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca countered that “it is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it. Life is long enough, and a sufficiently generous amount has been given to us for the highest achievements if it were all well invested.” People have felt that life is too fast and too full for some time. In On the Shortness of Life, Seneca argued that we misappropriate our time for transitory things. We should take more time for philosophical contemplation. That would provide “the love and practice of the virtues, forgetfulness of the passions, the knowledge of how to live and die, and a life of deep tranquility.” When we stop trying to be everywhere at once, we have enough time for the meaningful things.

There is more pressure today than ever to try to be in more than one place at a time, but it’s a pressure we need to resist. We especially need to resist the temptation to believe that technology will make it possible for us to be in all places at once. Andrew Yang’s holograms can host multiple events at the same time, in different places. But a hologram is an illusion and we know it. The same is true for us when we try to be in too many places at once. What’s on offer is not substantive reality, but the illusion of presence. Ask anyone who has sat across from you at dinner while you’ve been on your phone. Tech won’t make up for a lack of reasoned discourse and actual presence and interaction. It’s not continuous connection, but quality connection that we need. More than ever, what we need right now is a politics of presence.

1 comment

Nicholas Skiles

Amen

Comments are closed.