[Cross-posted to Mittelpolitanism]

Wichita, KS. My city of Wichita, KS, like so many other cities across the United States (and around the world), is busy engaging in a prolonged act of triage. Our county–after resisting for a time, before caving to reality–issued a stay-at-home order this week, and depending on how the coronavirus pandemic spreads, more stringent orders are almost certainly on their way, from our state government if not the local one. Now, with most businesses having closed their doors–joining libraries, schools, universities, and other public buildings–the question becomes the classic one which arises in every emergency, every instance of limited resources: what can be sustained, what can be changed, and what can’t be saved?

Every city dweller has their favorite spots, of course, we here in Wichita have a couple of websites we can follow closely, getting the latest information about what restaurants, coffee shops, delis, and retail outlets have online ordering, which ones have curbside pick-up, and which have simply closed for the duration. How well online patronage will help any–unfortunately, almost certainly not all–of these locales remain in operation over the weeks (and perhaps months) to come remains to be seen.

As much as I worry about my favorite Korean market, my reliable bagel breakfast cafe, or the local ice cream shop, though, I worry even more about the social spaces these businesses created. You don’t have to be an devotee of urban sociology or civic republican theory to recognize the immense value of “third places“–those locations where one is not at work, nor at home, but rather in an open-ended (while still closely defined) arena of connection and interaction. We’re talking about the YMCA, or the public library, or community centers–all of which, of course, have needed to close down to prevent people congregating and spreading the virus further. Places of commerce do this too–not all of them, and not all equally well, but some specialize in it. Indeed, for some the fact that they can provide a space for young and old, rich and poor, regulars and newbies, like-minded folk and trouble-makers, all to occupy a particular place and observe, listen to, laugh with, and learn from other actual flesh-and-blood human beings is exactly their business model. There are many establishments which may advertise this–but none embody it as well as bookstores (as the readers of Front Porch Republic, at least, should be very well aware).

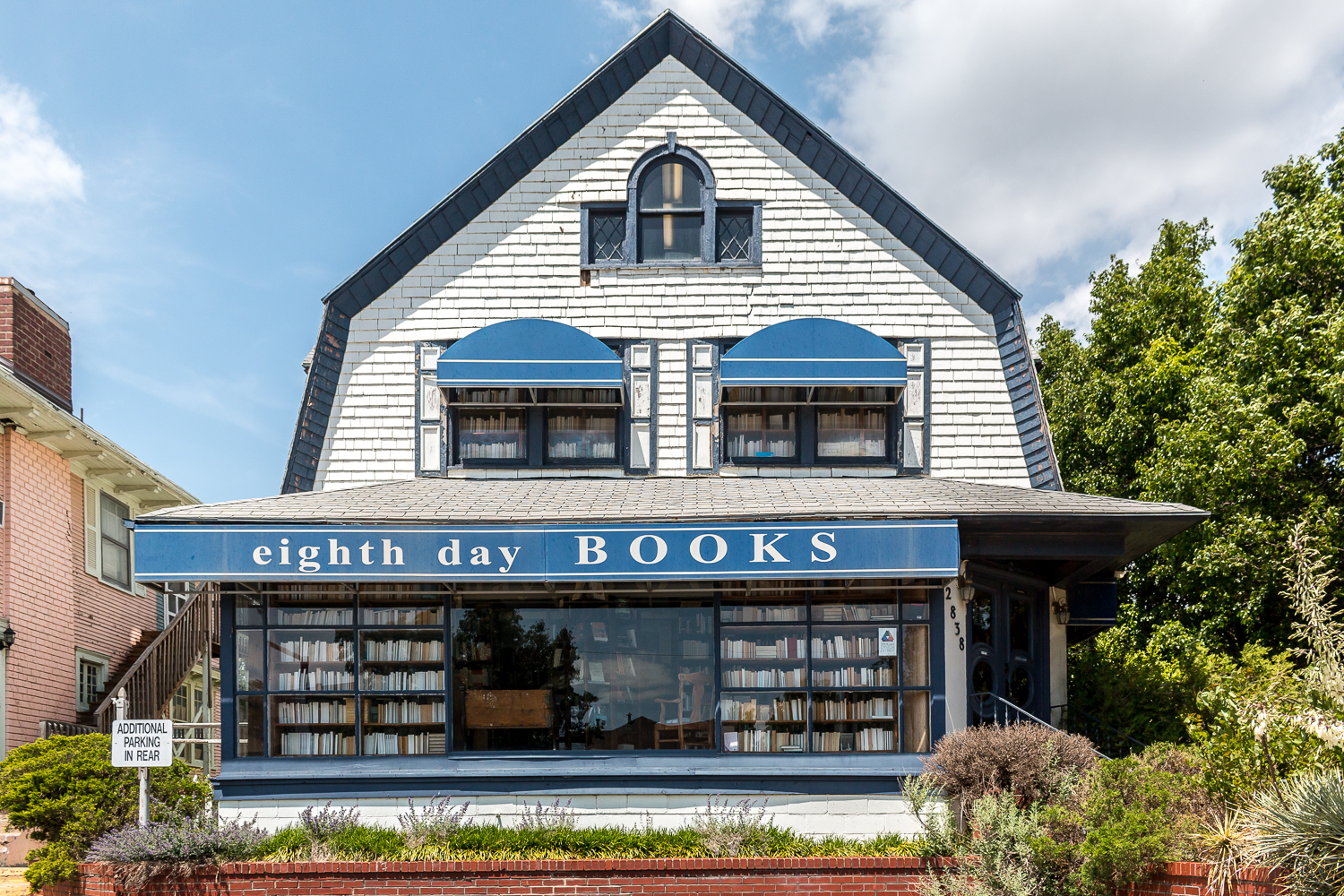

Watermark Books & Cafe (full disclosure: my wife worked there for over eight years) has had to cancel all its book clubs, reading groups, and story times. Sarah Bagby and her management staff have had to let their booksellers go, and close their doors, which has been a terrible loss for Wichita’s east-side College Hill neighborhood–to say nothing of the innumerable elementary and middle schools which Watermark regularly brought authors out to–which the store has become so entwined with over the years. Eighth Day Books, the tiny linchpin of a sprawling spiritual community (the Eighth Day Institute, of which I am a member) that connects churches and faith groups throughout the whole region, is focusing on online and phone orders, as EDI’s regular gatherings have had to be suspended, and access to the store limited, with the small, devoted staff of Eighth Day hunkering down to weather the storm. And Prairie Dog Comics, home of some of the best RPG game nights anywhere in the state (and where I buy my daughters copies of Ms. Marvel), has had to pack up its tables and end its evenings of gaming, restricting itself to fulfilling phone and online orders, and only allowing browsers into the store on a strict reservation basis. All of this, and more, doesn’t just threaten businesses–it threatens a by-product of commerce which is far more important that the commercial transactions themselves: namely, people getting together and sharing their literary passions, their spiritual insights, their geeky delights, with those in the same space.

In the larger sense, of course, cities have always been about the civic and commercial creation of such spaces. The reigning ideal of urban life, after all, is to live in a place where complex social connections could co-exist with what an old professor of mine once called “the private heterogeneity of anonymity“–that is, a place where we are sufficiently private to each other so as to allow all sorts of original communal, even unexpected associations to emerge, without the burden of the past traditions, prejudices, or authority. (This would be in contrast, he suggested, to “the public heterogeneity of familiarity,” the much more limited but perhaps also better known and more loved variety of connections which emerge in the hypothetical rural village because everyone knows everyone else’s idiosyncrasies so well.) That particular urban ideal is rarely achieved, obviously–and considering the importance of traditions to constituting just who we are, making the promise of anonymous opportunities for communal connection into an idol is plainly wrong-headed. The peculiar freedom of interdependent anonymity is by no means a perfect good. Still, its appeal is undeniable all the same. (Die Stadtluft macht frei hasn’t endured for centuries as a proverb for nothing!)

Recently Michelle Goldberg, a New York Times columnist, mourned seeing the people of New York City forced to isolate themselves. “Historically, cities have made it easier for people to live alone without experiencing constant loneliness,” she wrote, noting that choosing to live in a city is “to depend on interdependence.” To be isolated from one another, and in particular from those third places where the rich possibilities of community are most regularly realized–as they were and, God willing, still will be, at Watermark, Eighth Day, and Prairie Dog here in Wichita–strains urban interdependence as nothing else.

In some ways, a mid-sized regional city like my own might be better able to handle such a strain than many other, larger cities–which, unsurprisingly, is where coronavirus outbreaks have been most severe. Wichita dominates, but does not encapsulate, its rural surroundings; as such, it is at least theoretically possible for us to achieve Wendell Berry’s definition of urban sustainability–“a city in balance with its countryside”–in a way that NYC never could. More immediately, in this time of pandemic panic, we have a city where there is still plenty of space for the recommended (or mandated) isolation to take somewhat fulfilling–or at least less cramped–forms. Goldberg quoted a psychologist who observed how the varying impact of quarantine and the closure of beloved spaces depends much upon where you live; the loss of socially enriching spaces will be felt differently “if you’re able to stroll around your farm and pick the produce you’ve been growing,” in contrast to those who are “living in a one-bedroom apartment with three roommates” whom they nonetheless are supposed to keep themselves separated from. While obviously not every mid-sized city resident can easily get out to nearby farms to pick up fresh produce or meat from local butchers and producers, the obstacles to doing so in such places–or to even having immediate access to such resources on one’s own property–are far smaller than they are to residents of larger, more cosmopolitan agglomerations.

But at the same time, the residents of a city like mine, perhaps exactly because common places of complex interaction and community feeling are spread far apart and are relatively few in number (not to mention too easily bought out and torn down by local financial players), may find it, when a civic crisis arrives, that much easier to retreat to private locales, set aside public concerns, and forget about the ways in which a city could be made more resilient. In particular, cities like Wichita, centering as they do rural environments, have over the past century mostly just spread out, with little organic duplication and what little public investment exists having usually (and, as is now obvious to us urbanites obliged to endure one-size-fits-all quarantines, dangerously) entrenched a few central nodes within the city. This means, of course, that the prospect of making distinct neighborhoods more sustainable–whether via alternative transportation systems, divers and localized food networks, and other strategies for keeping cities’ cultural and commercial connections functioning–are politically that much less likely. We saw this, perhaps, in our county commission’s initial reluctance to face the questions of triage which this pandemic is making unavoidable. From what I hear from friends of mine across the United States, perhaps in your county seat or regional city, you’re seeing it too.

Whether you’re seeing it or not–but especially if you are–it seems to me that the task of every urban dweller at the present moment is to engage in whatever kind of triage our limited time and dollars allow, and to deliver them in whatever ways we can to help keep these wonderful third places alive, until the community connections they enable are able to fully bless our cities once again. Goldberg ended her column with a wistful hope: “Maybe when this ends, people will pour into their restaurants and bars like a war’s been won, and cities will flourish as people rush to rebuild their ruined social architecture.” Maybe. But that requires creating lines of support for that architecture in the meantime, so that all those the restaurants and bars–and, most crucially, all those bookstores, including three dear to my heart here in Wichita–will still be there, waiting for us to fill those third places with urban energy in a post-pandemic world.

When I talked this week with Warren Farha, the owner of Eighth Day Books, he expressed his determination to find a way through this challenge, and get to the other side. People–maybe not all the people, all the time, but enough of them, often enough–want and need to come into a place they know, among people they know, looking for the books and art and insight they know they will love, if they can only find it. “You can’t replace all that with online shopping; the door has got to be open so that people can come in and be part of something larger than themselves.” Maybe they’re not going to be able to come in for a time, he admits–but that just means their desire will be all the greater afterwards. No single city has an obvious blueprint of how to get from today’s closures to that “afterwards” celebration, whether tomorrow, or next month, or next year; New York City doesn’t, and neither does Wichita. My city here, just like yours, will have some advantages along the hard path before it, and some disadvantages too. One hopes that we’ll learn from this experience, and maximize the advantages in the future, and minimize the disadvantages, with cities both less expansive (to allow for more rural outlets) and less centralized (to allow for more neighborhood adaptability). But whether we learn those lessons or not, we ought to give thought to whatever lines of support are needed right now. Our common spaces, our third places, depend upon it.

10 comments

Gerry T. Neal

“Maybe they’re not going to be able to come in for a time, he admits–but that just means their desire will be all the greater afterwards. ”

Hopefully so. It seems to me, however, that this “universal house arrest” approach to combatting this pandemic is more likely to condition people into fearing ordinary social contact, which conditioning will remain, at least for a time, after the stay at home orders are lifted.

I appreciate your overall argument about the value of third places and the damage these measures will do to them. I argued here: http://thronealtarliberty.blogspot.com/2020/03/counting-cost.html that the cost of this hastily devised response to the pandemic was one that could not be reduced to something that can be measured in dollars and cents. I also took the position that the cost would be too high even if the economic factor were eliminated from consideration altogether.

Matt Stewart

I’ve been mourning the potential loss of third places as well, Russell. Hopefully the mourning is premature and that we’ll actually see a revival once things settle down.

The “private heterogeneity of anonymity” concept is clunky but useful. I have experienced it and enjoyed it in unexpected ways. What is interesting to me is the line where the anonymity starts to disappear, and whether people fight to sustain the anonymity out of some premonition that the newly revealed heterogeneity will kill the relationship that exists.

If moving beyond anonymity kills it, was it just not worthwhile anyway? Tentatively, I don’t think so–I think there is some value to these public relationships (and it’s one more reason I’m grateful that I don’t have a social media presence–Facebooking someone seems to kill these kinds of relationships very quickly), even if it would also be terrible to live in a world where only this kind of public life exists.

Russell Arben Fox

Great comment, Matt.

The “private heterogeneity of anonymity” concept is clunky but useful. I have experienced it and enjoyed it in unexpected ways….If moving beyond anonymity kills it, was it just not worthwhile anyway?

For whatever it’s worth, the scholar whom I drew this idea from–Stephen Schneck, my dissertation advisor at Catholic University of America two decades ago–actually speculated that, whether one is looking at urban anonymity or rural familiarity, the real heart of this social dynamic that needs to be preserved in “heterogeneity.” His fear was–though he didn’t use these words, in an essay written more than 30 years ago–the surveillance state, an urban environment where social knowingness is so omnipresent, and so thoroughly shapes our own personal choices, that what we end up with is a “public homogeneity of anonymity.” In the city, everyone has their private life, and everyone’s private life is the same, because everyone knows and is known in their privacy by everyone else. Makes me think your Facebook decision is a wise one!

Martin

Great article, Russell. So refreshing and encouraging to see someone look at the loss side of the balance sheet ignored in the incessant “safety first” meme, and express hope for restoration of third places. At the least, we should all appreciate daily and random interaction with more gratitude when the crisis is over.

In fact, socializing improves one’s immune system. Ironically, the over-emphasis on distancing (as you point out in examples of different living spaces, it’s absurd to impose “one size fits all”) will become counter-productive at some point:

http://sciencehealthandmore.com/loneliness-and-health-effects-on-the-immune-system/

Russell Arben Fox

I’m not as critical of the stay-at-home orders as I suspect you are, Martin, but I appreciate your recognition of how tabulating up the costs of these orders has to include the loss of “daily and random interactions.” There’s been some folks crowing against the Strong Towns/New Urbanist folks of late, talking about how much more resilient suburban and exurban places, not to mention rural towns, are than cities, since they have so much lower density and thus are far more likely to endure the virus. There’s probably some truth to that, but it makes the lack of the company of strangers into a virtue that it shouldn’t be. We’re social creatures, as Aristotle taught, and ignoring the different ways society plays out in our lives is I ideological blindness, I think.

Aaron

Russell:

And to think that this May, I was FINALLY going to get to visit 8th Day Books in person, and now I won’t be, since my sister’s graduation in Haviland is cancelled.

Maybe I’ll have to break down a pilgrimage just for that purpose. I’m thinking that 1,233 miles for the sole purpose of shopping for used books will be a sign of commitment, not a sign that I have a problem….

Aaron

Russell Arben Fox

It doesn’t have to be the sole purpose, Aaron–we’ve got other stuff to do in Wichita! Let me show you around.

Russell Arben Fox

I remember that blog post, Nicholas! Good to hear from you; I hope you’re all hanging on their in Canton. I should emphasize that Warren mentioned to me his gratitude for his online customers; there’s been a significant uptick in orders to the bookstore over the past couple of weeks, and it can’t just be people who would have come in otherwise ordering from him–rather, there really has been an increase, which he attributes to good-hearted people realizing that if they don’t help Warren pay the pills, this wonderful resource may not be around after its all over.

I’ve never really enjoyed online RPG’s before, but I admit part of that isn’t a principled Luddism, but rather just an unfamiliarity with all the tricks ZOOM or other platforms provide. I can’t imagine playing D&D with my brothers, but maybe I ought to start to try! Good for your friends giving it a shot.

Nicholas Skiles

Thanks for the response. It was nice to see that you’ve joined the board with Solidarity Hall by the way. I really appreciate the work Elias and Co. are doing. It seems like a good fit for you. Did you see my piece for the House Blog by any chance? Not my best writing. My FPR piece “Community and Intuition” was in many ways a rewrite. Anyway, the longer I hang around here, SH, Schumacher Society, Plough, etc, the more I notice the same names popping up. Grateful for our weird little web community.

Nicholas Skiles

So much to like to here. I have friends here in Canton that mail order from Eighth Day. We are stuck with mostly chain stores here. Some of them have a Catholic section, but Orthodox books are hard to come by. Eighth Day is a great resource for us. I hope to visit in person some day.

It’s not as special as when we could play in person, but some friends of mine are using some online resources to play DnD during all of this. Was also remembering my local comic shop back in Huntington, Purple Earth, which I mentioned in one of pieces back in June https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2019/06/mr-jones-and-me/

Here’s a podcast I sometimes listen to. In this one, Warren is interviewed at the end https://www.ancientfaith.com/podcasts/wildernessjournal/on_stillness#33314

Comments are closed.