Caldwell, ID. Two of the most widely read articles in Front Porch Republic’s history address the state of American education, and neither Jason Peters’s “Bar Jester’s Writing Seminar; or, How To Write Like the Average Undergraduate Male” nor Patrick Deneen’s “Res Idiotica” is sanguine about its future.

Readers sympathetic to the criticisms of Peters and Deneen might be heartened by the growth of classical schools, most of which are committed to education founded on the cultivation of virtue—Augustine’s “rightly ordered love”—and dedicated to serious study of languages and the great books. While the siren call of STEM is still music to most ears and classical schools are educating only a small percentage of American students (according to 2019 projections from the National Center for Education Statistics, about 90% of American students attend public schools), classical schools have grown steadily. The number of students being educated at schools associated with the Association of Classical Christian Schools has grown 189% from 2003 to 2019, with the number of affiliated schools doubling over the same time period.

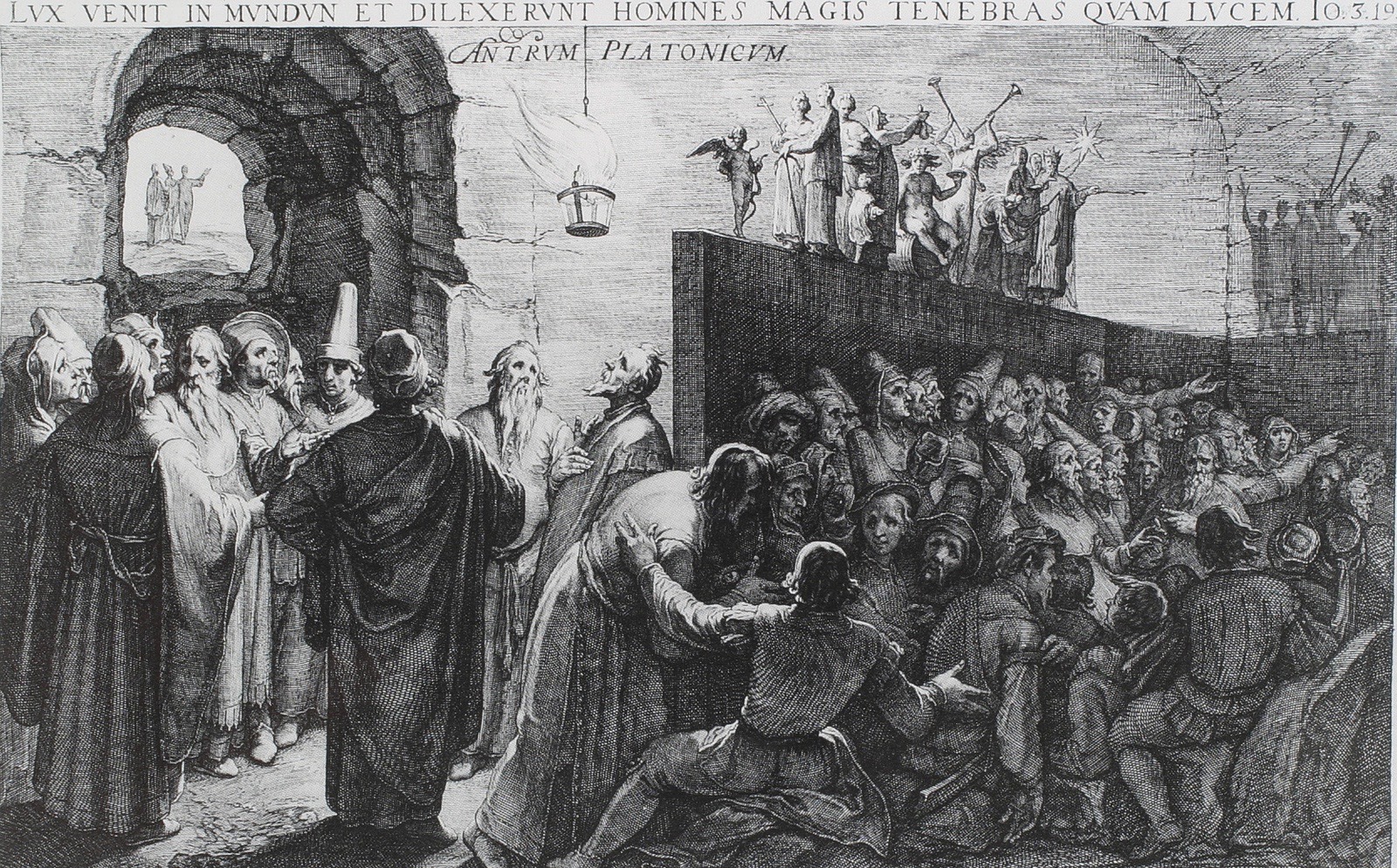

This interview started on February 25, 2020, the Tuesday after the American stock market first took notice of coronavirus, and about a month after the first confirmed U.S. case in Washington. Ohio became the first state to order a state-wide closure on March 12, just as we were preparing to discuss how to lead students off the screens and out of the pixelated caves that so shape even more of our present reality.

Joshua Gibbs, one of the respondents below, has been chronicling his own attempts to teach well during a pandemic. He teaches classical literature at Veritas School in Richmond, Virginia, and is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. Adam Roate teaches medieval literature at The Ambrose School and has also taught at Covenant Classical School in Fort Worth, Texas. Before teaching at Covenant, he developed and then taught a high school Great Books course for ten years. Amanda Patchin teaches medieval humanities at The Ambrose School and is a regular contributor at Front Porch Republic.

Stewart: After my first few months of teaching in a classical school, I realized that I had almost managed to forget about the “crisis of the humanities” that haunts humanities teachers in many other schools and universities. It struck me that I had not yet taught in an institution where the value of the humanities is simply assumed by most of the people in the building. Have classical schools successfully fended off the crisis of the humanities, at least internally?

Gibbs: I suspect a number of classical Christian schools in the country employ one or two teachers who quietly hold the opinion that Western lit classes are too white, too male, too old, and need to be restocked with fashionable books written in the last hundred years. Whether or not such teachers prove to be the leaven that—over the next twenty years or so—spreads through the whole classical lump will depend on how meticulously headmasters vet candidates for humanities positions.

Of course, many classical schools have healthy humanities programs wherein students are trained to virtue through reading and meditating on wise old books. At the same time, it has become increasingly common for parents to accost teachers and ask that their children receive higher grades. All manner of reasons are offered as to why their children should receive higher grades, few of which have to do with the quality of their work.

For the moment, then, I suspect most classical Christian schools have avoided the humanities crisis which has afflicted American colleges. If classical schools have a humanities crisis, it is not a question of whether the faculty will jettison Homer but a question of whether students actually want to understand Homer—or whether it’s all just posturing for a better offer from Babylon U.

Roate: If there is to be anxiety in classical schools over the humanities, I would say that assumed value is not the place to direct concern. In fact, many classical schools lean in too heavily on calling only instruction in literature and history the “humanities.” We see this most readily at conferences for classical educators where the vast majority of plenary and breakout sessions are devoted to thinking about and teaching literature, history, philosophy, and rhetoric. This can create an internal and external perception that other subjects such as math and science are simply not important to classical schools. The result is a transfer of students from our schools to schools that more explicitly emphasize STEM as core curriculum.

I think this problem is due, in part, to our tendency to truncate our definition of the humanities to include only the Trivium (grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric) at the expense of the Quadrivium (music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy). The association made here is that the humanities deal with the spoken and written word, while science and mathematics are concerned with the natural world and numbers respectively. This is a misnomer that can and should be corrected by looking closely at The Divine Comedy’s integration of humane knowledge areas throughout Dante’s journey. Taking Dante’s lead, I believe it is more appropriate to label the humanities as those areas of instruction which shape the affections of the individual so that they may become more fully human. While the language arts may help us articulate what it means to be human, the beauty and wonder found in the Quadrivium can help us to recognize our proper place in the created order. This too is humanizing, and, thus, should encourage classical educators to be broader in our consideration of what should be included in the “humanities.”

Patchin: I don’t know if success is a word that can be attached to any part of these endeavors: the time-horizon is too long. But, anecdotally, I have enjoyed living and working in a community that seems to assume that reading, at least, is a good thing. I don’t sense any anxiety about the importance of the humanities among my peers, but I do sense a defensive dismissal of the possibility of reading often or reading well among student families. Parents are often apologetically assured that “of course, they don’t have to read the stuff their kids do.” And they frequently assure me that they could never do what I do. There is a humility in this that is nearly as charming as the implied flattery, but there is also an assumption that big books are hard and probably not worth the effort.

It is clear to me the majority of my students are imbibing the implicit message of their homes that while the things we do at school are good, they are not good enough to demand any sacrifice of entertainment or distraction. If parents don’t exchange their phones for Aristotle, why should children? Worse, if teachers more often have their noses in their laptops than their books, why should they believe us when we say we love the latter? And, finally, how many of our students graduate our schools to return as teachers? How many major in philosophy? History? Literature? Humanities are all well and good within the walls of the classical high school, but they don’t stand a chance against the lucre of a STEM career or dopamine hits from Instagram and TikTok.

Stewart: Classical schools are more likely to fight against the tyranny of screens in education than other schools. In what ways have you attempted to lead resistant students out of the pixelated cave that is so relentless in its demands on all of us?

Gibbs: I hate social media. This winter, after more than ten years on Facebook and Twitter, I deleted both accounts and challenged every student in my school to do the same. I started a conversation with the senior leadership at my school about deleting the school’s social media accounts. I’ve given up on encouraging “responsible use” of these things. Having taught in the classroom before and after social media, I can well attest to just how bad both are for the heart and mind. It’s hard to teach art history now because Instagram has conditioned us to become bored with images in about two seconds. I lately penned an article suggesting students with smart phones and social media accounts should pay higher tuition rates because they’re such a profound liability. Some people took it as satire.

Over the last several years, I hypocritically preached against the evils of social media, though I justified keeping my own accounts open “for my career,” and I used social media for networking and gawdy self-promotion. While I claimed I used social media “to advance my career,” I actually used social media for entirely narcissistic reasons. I saw what social media did to intellectuals who I formerly admired— they often became self-obsessed (I’ll name Tony Esolen as an interesting exception to this claim). Eventually, I admitted social media had made me self-obsessed, as well. It had degraded my attention span, made me bored and boring, kept me up at night wasting time. I am now picking up the pieces of my personality, trying to reconstruct something which is truly classical, and preaching to anyone willing to listen.

Roate: It seems to me that the major knock against “screen time” for students in most classical schools is that screens tend to be used to promote hedonism in the lives of our students. Social media, even with all of its claims of “connecting” others over vast distances, tends to inculcate the false virtue of “me first” in its users. If you simply listen to how students talk about their experiences with TikTok or Instagram, you may notice that their chief desire in using these platforms is self-promotion or self-pleasure. A classical school that promotes the ideals of virtue necessarily fights against this tendency as each of the virtues we ask our students to contemplate and embody have a sense of the consideration for others implicit in their practice. Thus, our fight against the tyranny of screens is a place where our pushback, though countercultural, is warranted.

It is one thing, however, to tell students to stay off of screens by enforcing technology policies during school hours. Setting and enforcing these rules when students are on campus does not necessarily change how students engage with and think about technology beyond the classroom. I believe the teacher should model the virtues by which he hopes his students will live. With regards to screen time, this looks like staying off my many devices when an opportunity presents itself to engage in actual face-to-face conversation with my students. Attending to the needs of the conversation should be what my students remember when they think back to our interactions. Perhaps by showing them the good that results from neglecting their screens, we can lead students out of being beholden to every electronic notification they receive.

Patchin: I think that the first step in leading students away from the tyranny of screens is, of course, to lead oneself. In some ways, I feel like I’ve got this mastered: I haven’t ever owned a television, I rarely see movies, I don’t have social media (anymore…mostly…except for a rarely used Reddit account and Goodreads). However, it has become obvious to me that I and my fellow teachers are remarkably screen dependent. I do nearly all of my “work” on my laptop and often have my smart phone out on my desk. I use Google Slides for nearly all my lectures and do my lesson planning and lecture writing on the laptop as well. I check my email compulsively throughout the day.

I do wonder if I can break that tyranny in my work life. I’m expected to turn in my lesson plans online, and have had administrators counsel me to use more slideshows during lectures. I sometimes think that the right way to model a love of the enduring is to lecture from a large-format handwritten journal. To only show my student pictures in books and not on slides. To ostentatiously read books in front of them and to never open the computer where they can see. It sounds unbalanced, and yet, we live in a world tilted precariously toward the new, the stimulating, the flashing. Perhaps it is imminently balanced to step up to the other edge.

Now, excuse me, I have to go prepare materials for teaching online…

Stewart: Which book that you have taught has sparked the discussions that you have enjoyed most? Which book do alumni seem to remember most often, and for reasons that are satisfying rather than dismaying?

Gibbs: The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius. There are few books better suited to the teenage temperament. It’s about disappointment, pleasure, popularity, sex, food, money, power, desire, but it’s also about “the future,” which teenagers think about quite a lot. The Consolation is also a guide for introspection, which is a new and dazzling intellectual labor which, for most teenagers, has only lately become a possibility. Around thirteen or fourteen, God gives people possession of their souls. Before that point, most people are just doing what they’re told. But around this age, people become self-aware, startlingly self-aware, so self-aware, in fact, that they aren’t really aware of anyone else for the next several years. The Consolation is a book that can refine self-awareness into self-knowledge and self-effacement. It’s a remarkable little book.

Gibbs: The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius. There are few books better suited to the teenage temperament. It’s about disappointment, pleasure, popularity, sex, food, money, power, desire, but it’s also about “the future,” which teenagers think about quite a lot. The Consolation is also a guide for introspection, which is a new and dazzling intellectual labor which, for most teenagers, has only lately become a possibility. Around thirteen or fourteen, God gives people possession of their souls. Before that point, most people are just doing what they’re told. But around this age, people become self-aware, startlingly self-aware, so self-aware, in fact, that they aren’t really aware of anyone else for the next several years. The Consolation is a book that can refine self-awareness into self-knowledge and self-effacement. It’s a remarkable little book.

Roate: This is the first year in the past six years of teaching that I did not have the opportunity to work with students through St. Augustine’s Confessions, and I truly miss it. I remember the first time I was forced to read the Confessions for a Great Books class as a college freshman. Truthfully, I had no desire to take on the task of reading this spiritual autobiography and, in turn, read it absentmindedly. It was not until I was again assigned to read it in grad school that I found myself a better listener while also wishing I had paid better attention the first time through. These personal experiences with the Confessions have influenced my approach to the text with students. I am honest with them at the outset in telling them that if they are anything like I was in my late teens, they will likely not want to read or even like the Confessions. Despite this, I tell them, we will be working through it together and I will be reading it to them. This comes as a shock to many students who are accustomed to having readings assigned to be completed independently, but I make this move to help ensure that St. Augustine’s words are actually being sown in the hearts and minds of my students.

By the time we finish, the vast majority of students can point to one positive thing they received from the experience of listening to St. Augustine. This does not mean they universally love the book, but they do grasp some wisdom from the Confessions. It is the book most often recalled as we work through other medieval texts for the rest of the year, and it is the book I most often get emails and texts about from graduates who are picking it up again later in life. This is all I can really hope for when engaging students with Great Books—that the pebble that these authors drop into the souls of my students in the classroom becomes a powerful ripple by adulthood.

Patchin: I don’t teach it anymore, but when I taught Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations I was surprised and delighted with how students responded to him. It’s obvious to me, and apparently to a lot of teenagers, that our society could use a healthy dose of Stoicism. As I’ve moved to teaching Medieval Literature, I’ve been pleased to see students remembering and referring to Boethius throughout the year (we read it early). I guess I don’t know if either of those examples offer any insight though. I do think it is simultaneously surprising and unsurprising when students read and appreciate a great, old, book. Surprising because they are surrounded by an indifferent culture, indifferent peers, and—too often—indifferent parents. Unsurprising because what could be more worthy of appreciation?

3 comments

Aaron

I missed the Peters article. Just read it. I want to say that it was hilarious, but I don’t think it was intended to be, and despite being a comic genius myself, I’m having trouble laughing.

I’m going to think of this, the next time I grade a batch of history papers where it is averred that so and so played a “big role,” in “these events,” without which, “we wouldn’t be where we are today.”

Sigh.

Comments are closed.