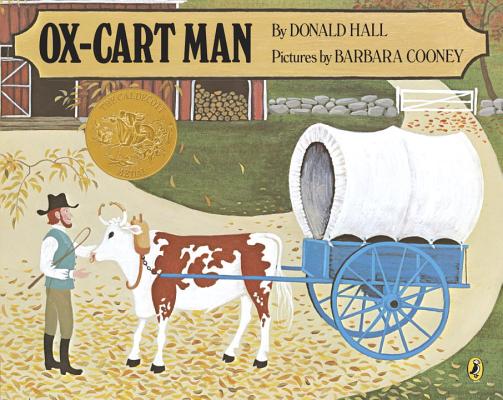

Unity, ME. This semester, I read to my college agriculture students a children’s story called Ox-Cart Man, by Donald Hall.[1] The students agreed that there was something good and beautiful in this tale of a 19th century New England farmer living a subsistence life with his family. Once a year, the ox-cart man would walk at his ox’s head, pulling a cart-load of the surplus goods that the family had grown or made, to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. There, he’d sell the goods, then the boxes and bags he’d carried the goods in, then he’d sell the cart, yoke and harness, then, “kissing his ox on the nose,” he’d sell the ox. With coins in his pocket, he’d walk through Portsmouth, picking up wares that would enhance his family’s life on the farm—a new carving knife to replace the kitchen knife his son was borrowing, a new sewing needle for his daughter, a kettle, and a few other items such as wintergreen peppermint candies. Upon returning home, his family would immediately begin preparations for next year’s sale: carving and sewing, fashioning a new yoke, and stitching new harness for the young ox in the barn.

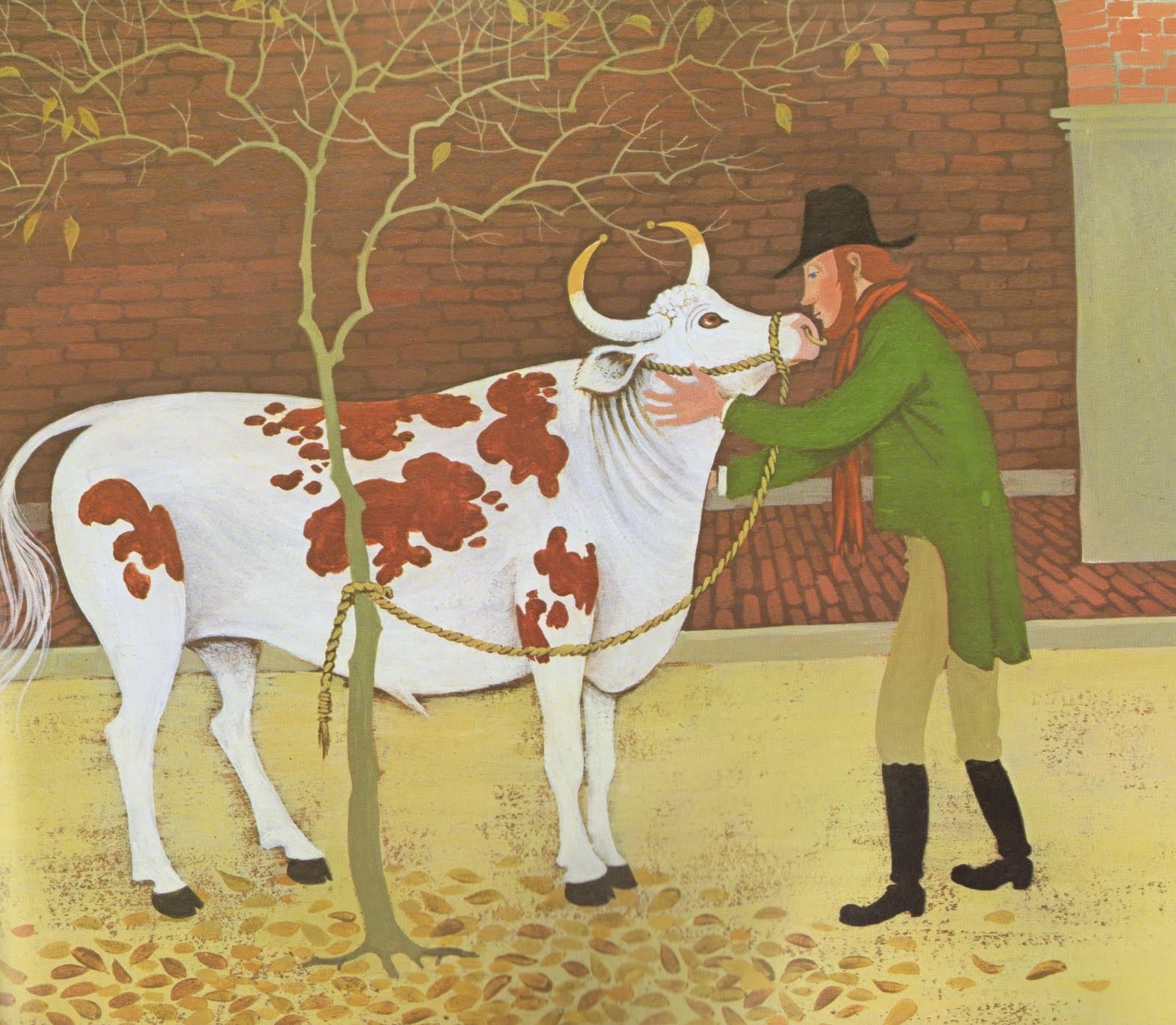

Against the backdrop of this story, we read about how in 2015 John Deere copyrighted some of its technology in a way that effectively eliminated the ability of farmers to repair or even adjust the tractors they thought they had purchased, outraging farmers and alarming justice advocates. Even though you purchase the tractor, “It’s [really] John Deere’s tractor, you just drive it,” says Wired magazine’s Kyle Wiens.[2] “From John Deere’s perspective, farmers don’t own their tractors; they merely enjoy ‘an implied license . . . to operate the vehicle,’” according to the George Washington Law Review.[3] Similarly, Monsanto has sued farmers for saving and reusing patented seed.

Few will side with the corporations who have placed these restrictions on farmers. If farmers of any stripe—industrial or organic—and consumers of any stripe—conservative, liberal, fast-food junkie, locavore–support the vision of independent and self-sufficient farmers, how can we make this a reality? Or, by what means can we recognize and adopt a vision for the future of agriculture inspired by the beauty and goodness of the ox-cart man?

Assessments of John Deere’s decision from a neo-liberal lens, founded on certain conceptions of liberty, containing within them implied conceptions of nature, community, and goodness would probably reinforce the validity of the contemporary agricultural situation over competing visions such as those evoked by the ox-cart man. This lens, inherited from the likes of Hobbes, Locke, and Adam Smith, sees human beings as separate and in conflict with one another, with any harmony of goals as accidental rather than constitutive.

Various philosophers and theologians have proposed a “post-liberal” approach based in pre-modern classical and Christian conceptions of nature, freedom, and the good. Post-liberalism emphasizes mutual obligation, positive freedom, and an immanent common good embedded in a transcendent good, with people seeking solidarity through friendship with other people, nature, and God.

In this essay I will use these two stories from agriculture to contrast a neo-liberal and a post-liberal approach with regard to their goals and rationales with a particular emphasis on the role of solidarity in each.

The Good as the Goal, and the Goal not to have Goals

In The Heretics, G. K. Chesterton summarizes liberal philosophy’s approach to discourse about what is good: “Let us not decide what is good but let it be considered ‘good’ not to decide it.”[4] Neo-liberal freedom is supposed to be neutral, leaving all decisions to each individual. According to Adam Smith, the aggregate of these self-interested decisions will providentially lead to a better world. And for Hobbes, the “war of all against all” will be tempered by the neutral leviathan of the violent State. In fact, say Adrian Pabst and John Milbank, the vacuum left open by this neutrality is filled by a notion of progress (always blind, for it can have no common aim) defined as an increase in wealth and self-expression.[5]

“Liberalism talks about the individual will, but it forgets that the will is always directed towards something. There has to be a purpose for freedom,”[6] says Pabst. Without recognition that there is some transcendent good towards which we should order our public and private lives, we are left with only undirected, indeterminate, autonomous individuals. “When all that says, ‘It is good,’ has been debunked, I want, remains. . . . I will still scratch when I itch,” writes C.S. Lewis.[7] Today, we see the “I want” not only expressed in wealth accumulation but wealth in collusion with technological novelty-seeking self-expression, cleverness for the sake of cleverness, constantly “elevating the possible over the actual.”[8]

Under the modern conception of freedom, articulated by neo-classical economics, there is no conflict between farmers and their suppliers of seed and tractors: companies are free to pursue self-interest, defined by profit and stock price, and consumers are free not to purchase a company’s products. Corporations have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize profits for their stockholders. Company growth is imperative because turning a profit is not enough. As a publicly-traded corporation, John Deere must grow to keep its stockholders happy. Customers and employees are secondary in importance. Our neighborly relationships to God, nature, and fellow humans are set aside in favor of the freedom of the autonomous individual.

But in what does freedom consist? Is it simply a matter of choice? Applying pre-modern, classical, and medieval conceptions of freedom, post-liberals might say that John Deere’s freedom to pursue profit through manipulating the legal system impinges on the farmers’ freedom to be farmers. The farmer is not free in a classical sense—the ability to flourish as a farmer; rather, it is abundantly clear that the farmer is more and more in bondage to equipment manufacturers, seed companies, processing plants, and biotechnology developed by universities and agro-industry labs.

Farmers have traditionally had a positive vision of what it means to participate in the good. This vision can include the larger economic community that includes both her suppliers and customers. In Ox-Cart Man, a virtuous circle of harmonious development is apparent. Good animal and crop husbandry, good craftsmanship, good neighborliness, and good parenting together form a good life. “Good” here is a goal not rigidly captured by any one definition but easily and commonly recognized, nevertheless. Virtue is always manifested in relationship—to truth, to one another, and to nature—and is reciprocal and reinforcing.[9] In a post-liberal conception, mutual recognition and support—solidarity—would be ever unfolding between John Deere and its farmers.

Means to Ends

Neo-liberalism has means to address the more egregious outcomes of modernity. It does so not to achieve an end, but to attempt to maximize freedom: judicious regulation by the State, redistribution of wealth, market competition, and a laser focus on GDP growth to lift all ships.

But none of these represent real solidarity as defined as mutual regard and assistance, let alone an end greater than the sum of its parts. Capitalism originated by appropriating the very productive activities highlighted in the Ox-Cart Man and eventually emptying them of publicly-recognized value beyond profit.[10] As capitalism matured, the craft knowledge and skills that lived in the artisan were concentrated in smaller numbers of people who design processes for workers–conceived as mere biological machines—to enact. The natural bonds between craftsmen were replaced by a reduced form of common interest in fair share and safety, united by their resistance to their employer’s goals of more work for lower cost. Similarly, as the middle class becomes proletarianized, so-called intellectual jobs are often limited to following recipes designed by someone else, and those recipes are closely guarded secrets held by a few at the top.[11]

Post-liberals recommend new forms of association between consumers and producers, such as worker-owned businesses or even bringing back the medieval guild in new forms, so that more people work within a larger vision which they have a hand in shaping. These intermediate associations—groups that live in the space between the individual and the state—are where genuine human interaction take place.[12] In these associations, formed naturally from intra-association common bonds and extra-association relationships, the common good becomes something beyond a collection of individual goods.[13]

What if John Deere’s loyalty were first to their farmer-customers rather than to their shareholders? Imagine representatives of farmers’ associations meeting with representatives of John Deere’s engineering department. What if these conversations started with understanding the common good that arises from healthy food in a healthy environment grown by a healthy community, and from there the conversation moved to what farmers need in a tractor?

These interactions include what can be described as “gift exchange.” Kenneth Schmitz and others have defended “gift” as a theological and ontological category.[14] John Milbank has brought this work together with the modes of gift exchange seen in primitive societies and applied the result to visions of a post-liberal economy.[15] The basic idea is that in an ideal economic transaction, more is exchanged than money. People open farms and restaurants because they feel that these will be good for the themselves and their communities, not simply for financial profit.[16] Our current economic thinking recognizes these goals as individual self-expression, if it recognizes them at all, missing the economic importance of the owners giving part of themselves in the exchange and receiving more than money back. In a community, the spirit that arises from these transactions is more than the sum of the parts.

In the Ox-Cart Man we see a productive enterprise where something beautiful emerges beyond the sum of the individual actions. The farm is small enough to manage well with good husbandry producing good products. The products offered for sale are the same ones experienced and improved upon in the home. This vision can be achieved more through internal development of a farm than through competitive expansion.

The Challenges to Moving Forward

Our neo-liberal society is characterized by insecurity, strong dependency rather than solidarity, a loss of meaningful work, cultural leadership by celebrity, technocratic determinism, and political and economic leadership by managerialists and technocrats.[17]

The John Deere example illustrates the vast disparity in wealth and power in America and the consequences of this inequality. The winners are increasingly those who are clever enough to find loopholes to get around laws or ways to use laws for goals outside their intended purpose.

Change will require more than legal wrangling and appeals to our better nature, for, as D. C. Schindler explains, the definition of “our nature” is one of the central issues. If our nature is autonomous and atomistic, then there is no real co-operation. The social contract is at best a “coincidence of individual goods” rather than a common good. If, instead, my human nature is such that I am able to pursue good for its own sake, “I transcend myself in my individuality and so open to others in an intrinsic way; I can be with others.”[18]

In addition, neo-liberalism’s understanding of science, technology, and the good–as already institutionalized in our liberal institutions–excludes the relationality necessary to ground a post-liberal society.[19] As Michael Hanby explains, the march of technocracy and technocratic rule “is essentially post-political,” and “the talk of a ruling elite is somewhat misguided”: “Technocracy is not rule by a tyrant or technocrat but the rule of nobody. Rule by technocracy is rule by a system without a seat or center, tyranny without a tyrant, social conditioning without conditioners.”[20] Even without facing oligarchic equipment suppliers, technology creates a social environment in which tractors drive the farmers rather than the other way around.

It will take more than poetic children’s books to change our thinking. But I’ll keep reading children’s books to my students, if for no other reason than that they are a good and beautiful way to begin the conversation.

Donald Hall and Barbara Cooney, Ox-Cart Man (London: Puffin Books, 1983) ↑

Kyle Wiens, “We can’t let John Deere Destroy the Very Idea of Ownership,” Wired. (April 21, 2015). https://www.wired.com/2015/04/dmca-ownership-john-deere. Accessed April 1, 2020. ↑

Chris Jay Hoofnagle, Aniket Kesari, & Aaron Perzanowski, “The Tethered Economy,” The George Washington Law Review 87, no. 4 (July 2019): 783-874. ↑

G. K. Chesterton, Heretics 12th edition (New York: John Lane Company, 1919) reprinted as e-book by Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/470/470-h/470-h.htm. Accessed May 7, 2020. ↑

John Milbank and Adrian Pabst. The Politics of Virtue. (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 13. ↑

Adrian Pabst, “From Liberalism to the Common Good” (Conference Keynote Presentation, Zermatt Summit, Switzerland, September 25, 2019) ↑

C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: HarperCollins, 1944), 65. ↑

Michael Hanby. “Before and After Politics: The Technocratic Fate of Liberal Order,” The Political Science Reviewer 43 (2019): 511-530. ↑

Adrian Pabst,”From Liberalism to the Common Good” (Conference Keynote Presentation, Zermatt Summit, Switzerland, September 25, 2019) ↑

Phillip Blond, Red Tory (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2010), 185. ↑

Matthew Crawford, “Shop Class as Soulcraft,” The New Atlantis. no. 13 (2006): 7-24. ↑

Adrian Pabst. The Demons of Liberal Democracy. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 109. ↑

D. C. Schindler, “Enriching the Good: Toward the Development of a Relational Anthropology,” Communio: International Catholic Review 37 (Winter 2010): 643-659. ↑

Kenneth Schmitz. The Gift: Creation (Aquinas Lecture) (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1982) 142 pp. ↑

John Milbank, “The Gift and the Given,” Theory, Culture & Society 23, no. 2 (2006): 444-447. ↑

Phillip Blond, Red Tory (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2010), 187. ↑

John Milbank and Adrian Pabst. The Politics of Virtue. (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 14. ↑

D. C. Schindler, “Enriching the Good: Toward the Development of a Relational Anthropology,” Communio: International Catholic Review 37 (Winter 2010): 643-659. ↑

Michael Hanby. “Before and After Politics: The Technocratic Fate of Liberal Order,” The Political Science Reviewer 43 (2019): 511-530. ↑

Ibid. ↑

3 comments

Doug Fox

Brian, Is this other essay of mine any more to your liking? https://macrinamagazine.com/theology/guest/2020/05/16/nature-and-culture-in-a-recovered-tradition/?fbclid=IwAR2JOIla0jPiaei_yNOM5L9fAAgWYGqe-2BpktwF5rWb4hS1JV4O_payEFc

Garth Brown

I remember a lot of talk when all this went down in 2015, and I recall an old Gene Logsdon essay in which he (tongue in cheek) suggested that the machinery companies won’t make a bare bones tractor because it would too successfully undercut their flashier options. Unfortunately, I don’t think this is the case. I think John Deere is giving farmers – at least the ones who give the most money to John Deere – exactly what they want. It takes big, fancy machines to efficiently crop thousands of acres.

I had a neighbor who bought a John Deere in the late 60s and was still running it when I moved here in 2010. I aim to take my cues from him. But, needless to say, machinery companies like customers who buy a new tractor every 5 years, not every 50. Until/unless profitable farming can be done at a smaller scale, I don’t see much hope of a return to simpler, more durable machines.

Brian

I think it would be far better for society if your lesson plan, with those two reading selections, was given to kindergarteners rather than college students.

Comments are closed.