Below is the introductory essay to the new issue of Local Culture, which is devoted to the work of Christopher Lasch. If you subscribe by September 1, you’ll receive this issue in your mailbox. You can whet your appetite by perusing the complete table of contents.

Over and against manifest follies that characterize American life in the first quarter of the twenty-first century there stands the wide-ranging work, keen and voluminous, of the historian and social critic Christopher Lasch. In the early years of the Clinton administration he said that “the old dispute between left and right has exhausted its capacity to clarify issues and to provide a reliable map of reality.” He noted that “in some quarters the very idea of reality has come into question, perhaps because the talking classes inhabit an artificial world in which simulations of reality replace the thing itself.”

That was in The Revolt of the Elites (1994). The book asked self-reflection of the nation’s absconding meritocrats whose talents seemed better-suited to poolside reflection, for in Lasch’s view they had become the very clerisy in a culture of narcissists. They were incapable, Lasch said, of the noblesse oblige to which older elites understood themselves to be duty-bound; they were actually at home in a global bazaar where they could disport themselves with the world’s other elites, devoted to certain versions of mobility—geographic and economic especially—that proved perfectly compatible with the kinds of social stratification that mobility was reputed to abolish. Despising in proper modern fashion the old aristocracy, they retained many of its vices but none of its virtues. And, being nobody’s fools, they knew that the best things in life, far from being free, require a great deal of money, and so they chased it, handing over judgment concerning their own interests to the all-absorbing market, which

puts an almost irresistible pressure on every activity to justify itself in the only terms it recognizes: to be a business proposition…. It turns news into entertainment, scholarship into professional careerism, social work into the scientific management of poverty. Inexorably it remodels every institution in its own image.

Lasch was dying of cancer (having declined to die of its cure) as he finished the book, but the nation it was urgently addressed to did not share its urgency. To the contrary, the nation had an appetite for events of greater pith and moment, among them a 232-day strike in Major League Baseball, the O.J. verdict, and the release of Disney’s Pocahontas. Two of our leading newspapers that did review the book also published a 35,000-word Manifesto by one Theodore J. Kaczynski, Ph.D. And now, as I write this in the year A.D. 2020, so ironically suggestive of the perfect vision belonging only to hindsight, it seems fitting to invite the culture to look back and judge the seriousness of itself reposed by its own reflecting pool, even as its prophets continue to go without honor.

But let not that culture be too chesty in its examination, for men and women Who Know are first-rate adepts in the rituals of writing, taking, and acing their own purity tests. And good grades are especially easy to make if you refuse to honor your prophets. To those who might have noticed, for example, that American public education was the world’s envy until the 1960s, when decline by reform began in earnest, such spotless report cards should signal the dangers that lie in their indifference to Lasch’s most prescient insights: that the history of reform in education, which is the history not of conservatism but of liberalism, has predictably led to illiberalism, in large measure for want of a sufficient concentration of its own vaunted humanitarianism; that this failure points to a severely limited open-mindedness among the open-minded; that social planning by the vicious will not produce a virtuous society; that such laudable goals as compassion cannot be achieved by “goodwill and sanitized speech”; that democracy “requires a more invigorating ethic than tolerance,” which is a “fine thing” but “only the beginning of democracy, not its destination”; that identity politics makes a poor excuse for religion, “or at least for the feeling of self-righteousness that is so commonly confused with religion”; that there is little to be gained by “fierce ideological battles … fought over peripheral issues”; that “the neighborhood is more truly cosmopolitan than the superficial cosmopolitanism of the like-minded,” and that “diversity—a slogan that looks attractive on the face of it—has come to mean the opposite of what it appears to mean,” in practice legitimizing “a new dogmatism, in which rival minorities take shelter behind a set of beliefs impervious to rational discussion.” Lasch went so far as to say that we betray the civil rights movement when we make race a matter of victimhood (“it was the strength of the civil rights movement,” he wrote, “that it consistently refused to claim a privileged moral position for the victims of oppression”). For Lasch seems to have been of the unacceptable opinion, at least in his last book, that abandoning old ideologies “will not usher in a golden age of agreement. If we can surmount the false polarizations now generated by the politics of gender and race, we may find that the real divisions are still those of class.”

But then this was at the heart of Lasch’s late criticism of public life in America: “the elites that set the tone of American politics, even when they disagree about everything else, have a common stake in suppressing a politics of class.” The gap between them and the rest of us must remain, lest the agony of revolt be visited upon them.

Besides, how else to secure such amusing surprises in public life as November 2016? Not to gainsay the palpable mischief that followed, for Mr. Trump has managed to bring out the worst in just about everyone, and that includes the elites, but is no one else amused at the gymnastics of, say, the New York Times trying and failing to understand an election it tried and failed to predict? The certified diverse members of its confused news room might wish to leave off rewriting the year 1619 and consult the books of a dishonored prophet—if, that is, achieving a little clarity on the dysfunction of public life and discourse prove more desirable than recoding the American brain to suit the moment’s prejudices. Its vaunted “Here’s What Else is Happening” pages might feature fewer stories on drag queens and more on middle Americans suffering the economic consequences of investor-class joy-riding.

I mentioned above the betrayal of the civil rights movement. It deserves at least a little elaboration. In The True and Only Heaven Lasch noted that Martin Luther King’s difficulties in bringing the civil rights movement north, specifically to Chicago, were due in large measure to the fact that “the North lacked the stable black communities on which the civil rights movement rested in the South.” King “did not join in the criticism directed by black militants and newly radicalized white liberals against the Moynihan Report, accused of shifting attention from poverty to the collapse of the family and thus ‘blaming the victim’ for the sins of white oppression.” In Lasch’s judgment an “important difference between the North and the South lay in the demoralized, impoverished conditions of the black community in cities like Chicago, which could not support a movement that relied so heavily on a self-sustaining network of black institutions, a solidly rooted petty-bourgeois culture, and the pervasive influence of the church.”

In fine, the nonviolent strategy that had worked in the South was ineffectual in the North, where living conditions characterized by poverty, familial dissolution, and the absence of mediating institutions did not conduce to the southern strategy. Whether Lasch remained to the end a man of the Left, as Wilfred M. McClay states (herein), or whether he had moved beyond both Left and Right, as Eric Miller has implied in Hope in a Scattering Time, his biography of Lasch, it is nevertheless the case that Lasch, in pointing to the necessity of strong families and viable mediating institutions, was surrendering his liberal bona fides at a time when fewer and fewer remained to him.

He was clear enough about this in his blistering remarks, published in Harper’s, on Hillary Clinton’s campaign for children’s “rights” and her attempt to liberate children from their families in a manner analogous to the liberation of blacks from slave-owners and women from men. The essay’s biting title was “Hillary Clinton, Child Saver.” “In a society composed of sovereign individuals,” Lasch wrote,

the family becomes a political battleground on which the generations confront each other as adversaries, each appealing to outside forces in the hope of shoring up their own position. The older generation is attracted to the political slogan of “family values,” the younger to the growing campaign to give the rights of children the full protection of the law.

Into this dispute stepped a self-appointed referee whose “writings exemplify the view of families that so many working people find objectionable. From her perspective, the ‘traditional’ family is, for the most part, an institution in need of therapy, an institution that stands in the way of children’s rights—an obstacle to enlightened progress.” Such, Lasch implied, explained the defection of “‘Reagan Democrats’ from a party that no longer seemed to care about people engaged in the hard work of raising children.” And in any case he minced no words: “her writings leave the unmistakable impression that it is the family that holds children back, the state that sets them free.”

If Mrs. Clinton acknowledged that people, children included, also need protection from the state every now and then, she failed to understand that “the best defense against the state is the informal authority exercised by the family, the neighborhood, the church, the labor union, and all those other intermediary institutions that make it possible for communities to educate, discipline, and take care of themselves without calling on the state.”

Moreover, she argued that when children are dependent upon their parents, they are “discourage[d] from taking responsibility for themselves,” though dependence on the state would apparently not have the same effect. Lasch would have none of it:

The growth of the welfare state weakens those institutions, and reformers then cite the resulting disarray in order to justify another dose of the same medicine. Far from encouraging individual autonomy, however, the welfare state turns citizens into clients. Clinton thinks it would be a good thing if young people could “organize themselves into a self-interested constituency” like other victims of discrimination. She does not seem to see that dependence on the state is no better than any other form of dependence—worse, in the case of those who are necessarily dependent by virtue of their inexperience.

Lasch followed instead the analysis offered by Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which long ago had pointed out that “professional supervision” concocted by reformers is a waste of “normal, casual manpower for child rearing.” According to Lasch, Jacobs had demonstrated that healthy neighborhoods encourage what she called “casual public trust”; they

teach children a lesson that cannot be taught by educators or professional caretakers; namely, that “people must take a modicum of public responsibility for each other even if they have no ties to each other.” When the corner grocer or the locksmith scolds a child for running into the street, the child learns something that “people hired to look after children cannot teach, because the essence of this responsibility is that you do it without being hired.”

Having thus incurred the ire of the Left with his remarks, Lasch played equal-opportunity with the Right: parents who do not wish to surrender their duties to the state are “perhaps the most conservative group in the country,” and yet “conservatism” betrays them, for it is an ism

that begins and ends with a celebration of the free market. Republicans may hate what is happening to our children, but their commitment to the culture of acquisitive individualism makes them reluctant to trace the problem to its source. They glorify the man on the make, the smart operator who stops at nothing in the pursuit of wealth, and then wonder why ghetto children steal and hustle instead of applying themselves to their homework.

The Right, having refused to “indict the market in the collapse of the family,” was essentially sounding the fox horn, which is to say inviting the Left into the hunt for legitimacy amid its “party’s declining fortunes.”

By looking at the “children’s cause” through the eyes of hard-pressed parents, they can make “family values” more than an empty phrase. They can begin to heal racial divisions by showing that when it comes to children, all families want the same thing: protection from an intrusive commercialism that corrupts the young and undermines parental authority…. What they all need is a protected space for their children to grow up in.

This went over about as well with the Left as Lasch’s criticism of another progressive orthodoxy: “A feminist movement that respected the achievements of women in the past,” he wrote in Women and the Common Life: Love, Marriage, and Feminism, “would not disparage housework, motherhood or unpaid civic and neighborly services. It would not make a paycheck the only symbol of accomplishment. It would demand a system of production for use rather than profit. It would insist that people need self-respecting honorable callings, not glamorous careers that carry high salaries but take them away from their families.”

Toward the end of his career Lasch took an interest in—and became broadly informed on—the enduring properties and dangers of that ancient heresy, Gnosticism, on which he wrote several essays for New Oxford Review and Salmagundi. This was no intellectual dalliance. Rather, it sprung organically from the soils of Lasch’s intellectual disposition and his seemingly effortless ability to intuit and name the maladies that are so inimical to human flourishing. Allowing for a very broad definition of Gnosticism—that Creation and Fall are the same event, that the physical world impedes our return to the realm of pure mind or spirit, and that salvation comes not by love or grace but by knowledge (and knowledge granted to a privileged few at that)—granting this definition, we can see why Lasch thought it necessary to recognize and name this ancient menace, newly returned to work its woe on a technological society in permanent departure mode. I single out but two aspects of his thinking, both rather obvious, that played into this late interest: (1) the mistake of trusting our elites who (2) have long been engaged in a flight from this world. It seemed a merely passing remark when in The Revolt of the Elites Lasch noted our “loss of respect for honest manual labor.”

We think of creative work as a series of abstract mental operations performed in an office, preferably with the aid of computers, not as the production of food, shelter, and other necessities. The thinking classes are fatally removed from the physical side of life—hence their feeble attempt to compensate by embracing a strenuous regimen of gratuitous exercise.

He indicted them for having “no experience of making anything substantial or enduring” and for being mere consumers of productive labor. “They live in a world of abstractions and images, a simulated world that consists of computerized models of reality—‘hyperreality,’ as it is has been called—as distinguished from the palpable, immediate, physical reality inhabited by ordinary men and women.”

But Lasch clearly regarded this as a Gnostic resurgence. And who should be surprised by this rough beast, its hour come round again, slouching toward Silicon Valley to be born? “The ‘postmodern’ megalopolis,” he wrote in New Oxford Review, “has given rise to forms of social life uncannily reminiscent of the Hellenistic empire,” which he called “sprawling” and “polyglot” and which suffered the “decline of small property and local self-government,” the absence of which created a vacuum that political and economic centralization were (and are) quick to rush into.

But the similarities did not end there: “The militarization of government and civic life was an added discouragement to any form of popular participation. The widening gap between the rich and the poor did not prevent a rapid circulation of elites or the rise of a parvenu class that was widely traveled and superficially sophisticated but only half educated.” In short, “the second century was a time when the accumulation of wealth, comfort, and knowledge outran the ability to put these good things to good use. It was a time of expanding horizons and failing eyesight, of learning without light and great expectations without hope—a time very like our own.” In Lasch’s view Gnosticism “could take shape only in a climate of the deepest moral confusion.” He had learned from reading Wendell Berry’s The Unsettling of America that contempt for the physical world and the life of the body in it leads inevitably to the destruction of both. But what more could a world-despising Gnostic ask for than release from the world and the body born into it—except maybe a few more technological shortcuts through the splendid messiness of this one life?

You can join the madding crowd of politicized intellectuals in condemning Lasch as a man who couldn’t mind his business as a historian. But Lasch was clear about the study of history. A properly “prophetic” study of the past, he wrote in Salmagundi, as opposed to a mere scholastic curiosity about it, puts itself to the important task of the criticism that is essential to the examined life. “Here the study of Gnosticism,” to take but one example, “is shaped not by questions growing out of a tradition of specialized scholarship but by the suspicion that an understanding of the gnostic sensibility will shed light on the spiritual condition of our own times.”

Historical scholarship becomes a form of philosophical and cultural criticism…. Gnosticism commends itself as an object of study, to those with a speculative turn of mind, not because new information has come to light or because gaps in the scholarly record remain to be filled but because it is important for the modern world to understand how it lost its way and might regain it.

Lasch believed that our grip on the real world—not just the “environment” but “our human home”—was weakening. Our sustaining traditions, our mediating institutions, our privileges of association—all were being dismissed as parochial by the greater parochialism of the elites. And so “an ancient dualism reasserts itself as a plausible description of existence”:

the world is a wilderness, a madhouse, a living hell, escape from which (whether in space ships or suicide, in daydreams, in carefully engineered revivals of old superstitions, or simply in a kind of cultivated inattention) holds out the only hope of freedom.

Gnosticism, “the faith of the faithless,” is as well-suited to us as it was to those living in the second century. “We can expect many people, still only dimly aware of its undeniable attractions, to fall on it as a religion seemingly made to order for the hard times ahead.” For, again, “the talking classes inhabit an artificial world in which simulations of reality replace the thing itself.”

Such was Lasch’s cast of mind, and such was his rhetorical power in plain style. Philip Lee rightly noted in Against the Protestant Gnostics that in the New Testament the formulation isn’t escape from the world but pilgrimage through it. It is a notable feature of Lasch as a man—as distinct from Lasch as a social critic or historian—that, even in the late stages of cancer, he chose pilgrimage, not escape. And then Valentine’s Day 1994 beheld the end of a journey that most agree was far too short.

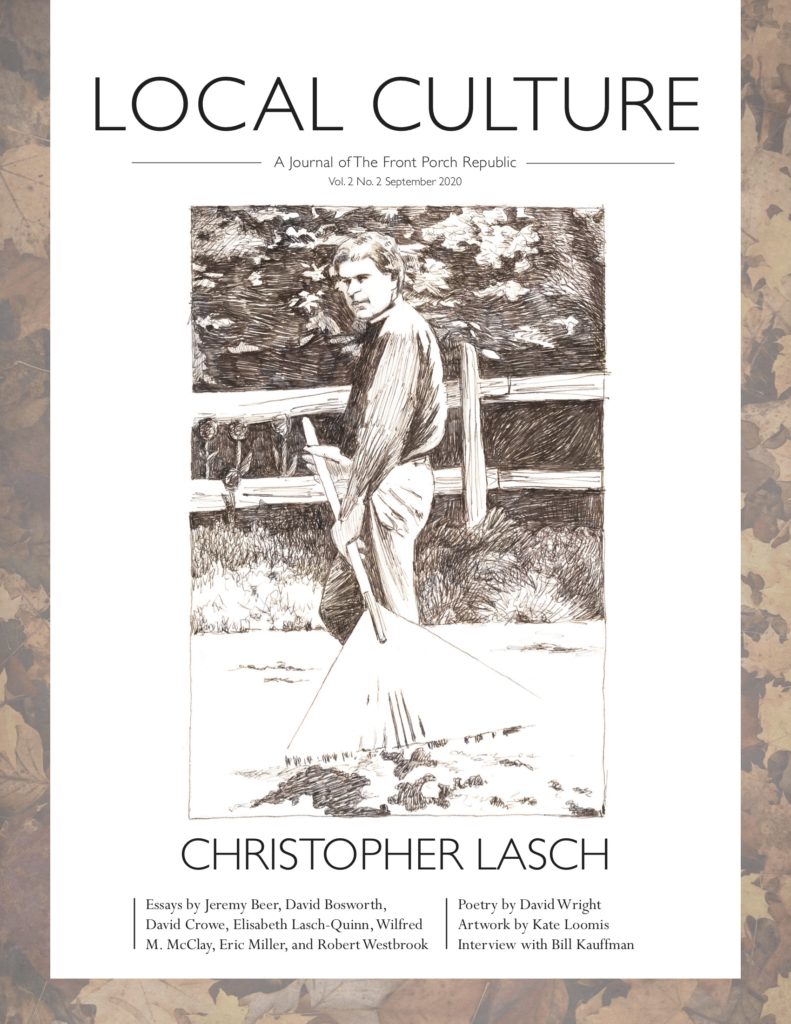

Local Culture is pleased to feature the artwork of Lasch’s daughter, Kate Loomis. The cover is a pen-and-ink drawing from a photograph of Lasch, ca. 1980. I am grateful to Lasch’s other daughter, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, not only for her reminiscence here but for the photographs included in these pages. Readers may be interested to know of an online bibliography of Lasch’s work compiled by Robert Cummings at Truman State University: https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/3271.

7 comments

Will check back

Can I purchase the lasch issue of the magazine?

Jeffrey Bilbro

Yes! Email me for details: jeffbilbro@gmail.com

Geoff Chapman

The same with me. Ran into you via Mars Hill and subscribed, and would love to get the Lasch issue, and the first two issues if possible! Thank you for what you are doing!

Clifford S Morton

I just subscribed today! How can I get the Lasch issue of the magazine? Are any of the older conferences recorded? I discovered you site through Mars Hill Audio.

Jeffrey Bilbro

I’ll get your name on the list for the Lasch issue. And while most of our conferences haven’t been recorded, a few have. Links are here: https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/fpr-conferences/

Brian Thorn

An excellent article,

Dr. Peters! Lasch truly showed how elements of “left” ideology in terms of class politics went alongside a “rightist” viewpoint on gender and sometimes racial politics. I appreciated the remarks here on Lasch’s respect for manual labour and for “middle Americans.” I learned a lot from Lasch’s A True and Only Heaven on critiques of progress. Thank you for writing this!

Comments are closed.