Buncombe County, NC. In 2010 Kristin Kimball published The Dirty Life: A Memoir of Farming, Food, and Love. In that volume Kimball describes her first encounter with Mark—the tall, lean farmer she would eventually marry—and chronicles their courtship, which included the work required to launch a farm in upstate New York built around the idea of a whole-diet CSA. Their ambitious plan was to provide their membership with not only a weekly ration of vegetables and fruit, but also meat, milk, eggs, grains, syrup from their sugarbush, and firewood. They envisioned doing their work—plowing, cultivating, and harvesting—with draft horses. Given their diversity of production and their primary power source (the sun), Essex Farm would be modest in size by design.

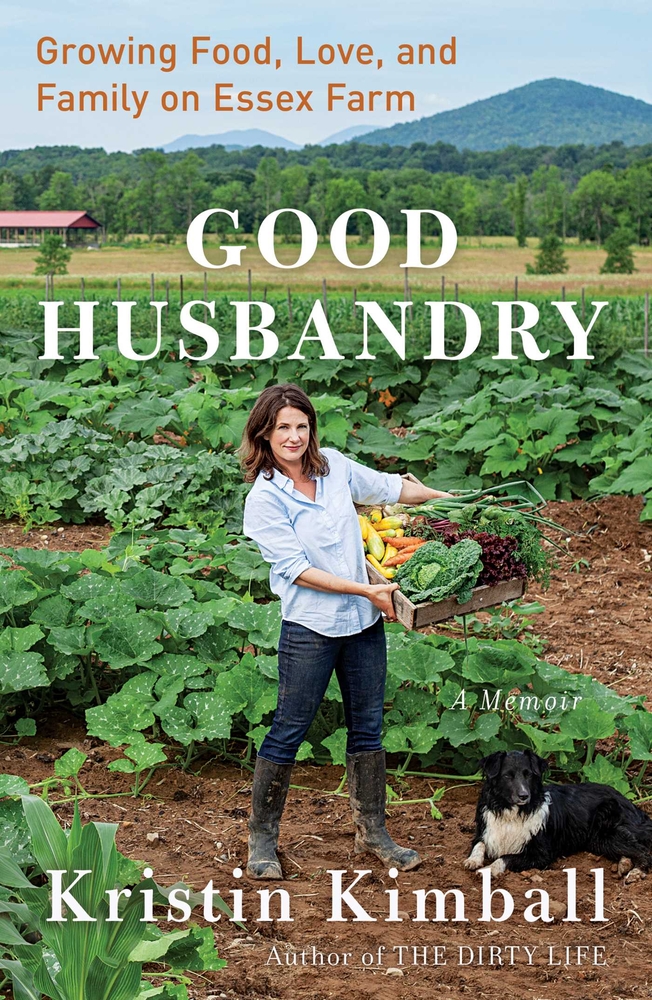

Good Husbandry: Growing Food, Love, and Family on Essex Farm, published in 2019, describes the handful of years that came after the Kimballs’ marriage and business began. Kimball’s subtitle provides a fair summary of her themes. Within the pages of her memoir, she describes the farm and farming as the anchor, bulwark, and joy of her family’s life, even while its rough edges fray her relationship with Mark.

I. Farming as “Organizing Principle”

Kristin Kimball was not born to farming. In fact, she defected from a life pretty close to its opposite: before meeting Mark, Kristin worked as a travel writer who lived out of a small apartment in New York City.

As someone who chose rather than inherited an agricultural life, Kimball is able to offer some frank appraisals of farming. She warns that farming is not “easy and it is not going to make you rich” (263). Value, when it arrives, sometimes comes unexpectedly and in bizarre forms. For example, Kimball insists that the work itself is rewarding: “when you look at a farm from the outside, it looks like work is the cost. From the inside, you find that the work is the reward or, rather, the work is all there is, and it’s a beautiful thing” (282).

In Good Husbandry Kimball echoes much of what she emphasized in The Dirty Life about the importance of agricultural work being physical:

We have bodies, and it generally feels good to use them. It feels especially good when we use them for a purpose, toward something we believe. It is a simple thing but profound, and it is easy to lose sight of in a world that places more value on work that happens inside, on a screen, while seated at a desk. (68)

Along with the work that farming generates, Kimball appreciates the way that farming provides “a strong organizing principle” (263). The demands of farming, Kimball says, make “everything else fall into line.” She describes her family’s life as rotating around “a heavy rod of daily need: the plants need, the animals need, the farm needs.” Kimball writes that all of that need is “not a curse but a blessing”; however, having the farm and its demands as the axis of her life does create some friction points, especially when her family’s needs increase exponentially.

II. Family Life on Essex Farm

The Kimballs’ family doubles in size after the arrival of their two daughters. This entry into parenthood changes Kristin’s perspective. In Good Husbandry, she frequently contemplates the way that the course she charted for her life automatically affects her children as well.

Kristin elected to live a life rich in land and food but poor in cash, but becomes acutely aware of what that means for her children after her older daughter comes home and asks why she has a home-packed lunch while the other kids have brightly wrapped “things from the store” (250). Kimball’s justification—“Food . . . is what we do. It is one of the things that makes our family special”—seems to satisfy the child, at least for the time being. Kimball recognizes, though, that the kind of childhood that accompanies growing up on a farm—one that includes haircuts at home, high-mileage cars, and an unfinishable chore list—may eventually feel like deprivation.

Of particularly great concern to Kristin is the condition of the farm house where she, Mark, and the girls live. Before children, Kimball tolerated the severely worn and dirty state of her house because she chose to put the farm first. It was more efficient, the Kimballs reasoned, to feed the entire workforce at the same large table and for the farm office and all of its detritus to occupy a room in the house. Her mother looks at the condition of the Kimballs’ home and says, “you owe your child a better life than this” (103). Eventually, Kristin comes to agree with her mother. Her re-appraisal of the house’s role on the farm sets the stage for a showdown with one of the most eccentric characters found in farm writing.

III. Mark Kimball as a Character

For this particular reader, some of the most memorable moments in Kristin Kimball’s writing are the details and anecdotes she shares about her husband. Mark Kimball (he took her last name when they married, by the way), stomps through the pages of Kristin’s memoirs as a kind of flesh-and-blood embodiment of Wendell Berry’s “Mad Farmer.” Close cousin to self-described “lunatic farmer” Joel Salatin and “contrary” farmer Gene Logsdon, Mark rejects or rethinks any convention he finds limiting or flawed. He does not, though, restrict his revolutionary thinking to farming. I remember from The Dirty Life that Mark wears his shirts inside-out half of the time so that they will wear evenly. When he and Kristin skyped with a Food Writing class I was teaching several years ago, he insisted that it would make perfect sense to grind and eat draft horses after they reached the end of their working lives.

Kristin stocks Good Husbandry with more of Mark’s musings. Tired of chasing down matching socks and mittens for his daughters, he draws up a one-piece sack that would dramatic simplify the attiring of infants. Mark also imagines doing away with dinner plates. Why not eat directly off of the kitchen table, he asks, and then use a sheetrock knife to scrape all the residue into a bucket? Finally, Mark feels “true and deep-rooted antipathy toward the idea of fixing anything” in the Kimballs’ house (285). To him, all of their investments should go into the farm since it generates income. Spending money to improve the house, by comparison, would only make them more comfortable—an idea he finds anathema. (Mark disdains comfort; we learn in Good Husbandry that Mark takes his vacation by windsurfing in New England in January).

On the one hand, Mark’s eccentricities liberate Kristin. Because his ideas and notions run so contrary to the norm, she is free to cast off some of the thinking about farming and parenting that doesn’t make sense to her. For example, their oldest daughter spent “every night” of her second winter “sleeping in a pink snowsuit, cozy against the cold” inside their home. Kristin sees this as “a solution to the problem of keeping blankets on a toddler that seemed perfectly reasonable to me, then and now” (101). And to a degree, she shares in Mark’s thinking about frivolous, HGTV-driven home makeovers. Whereas others might be “house-proud,” she describes herself as “food-proud, land-proud, and work-proud” (103).

On the other hand, some of Mark’s thinking situates him in opposition to his wife. The pages of Good Husbandry do not suggest that Mark convinced Kristin—an avowed “horse person”—to slaughter and consume their retired horses. Kristin also insists that plates are to be used at all meals and that children wear clothes (not sacks) because they are people. And eventually Kristin converts the farm house into a far more domestic space by carrying out some modest renovations after moving the farm’s office out from underneath the home’s roof and expelling all of the farm workers from the kitchen table.

IV. “The Problem of Scale”

Re-defining the farm house as a space exclusively for family marks the way that Good Husbandry is about a period of transition. The growth of the Kimballs’ farm and family brings change and adjustment.

Essex Farm began with a labor force of Mark and Kristin. Over time they were joined by a steadily growing but ever-changing array of farmers. When there were only four adults, gathering everyone around the same table was both logical and pleasant. Kimball writes that during those early years the full workforce felt like an extended family. Even much later, when more than a dozen people crowded around the table or spilled over into an adjacent room, meal times still felt magical. Thus, requiring those working on Essex Farm to eat elsewhere indicates a tectonic shift. Kristin seeks to create some kind of separation between business and family. She makes clear that navigating that change takes years, in part because the farm is also changing.

The farm alone brings enough challenges to fully occupy the Kimballs. As Essex Farm scales up, they must constantly re-consider how they go about their work. Kimball writes that “Scale is just scale, but it’s everything in farming. Scale dictates the equipment you use, the infrastructure you need, the labor you employ” (194). As Kristin contemplates the dilemmas presented by growth, she visits or mentions farms that have answered “the problem of scale” in a variety of ways. She knows of farmers who grow microgreens on a single acre and others who operate a 1500-cow dairy. Essex Farm falls in between those two extremes, but its growing membership requires changes. The Kimballs switch from hand milking to milking machines. They turn to larger and larger hitches of horses so that they can plow and cultivate their acreage more quickly when conditions are right (or close enough). Later, they scale back on their use of draft horses when their workforce does not include enough experienced teamsters. On the decision to use their horses less, Kimball writes, “I didn’t think we could hold up our end of the deal with the horses and keep the farm going at its current scale” (277). Essex farm eventually returns to relying largely on biological horsepower once the Amish move into their region in significant numbers.

In some ways Good Husbandry stands as a kind of bildungsroman for the support-your-local-farmer movement.

In some ways Good Husbandry stands as a kind of bildungsroman for Essex Farm and, by extension, the support-your-local-farmer movement. The Kimballs’ farm is nearing its twentieth birthday. Several of their former employees now operate farms of their own, some nearby. Thus, Essex Farm has met with enough success to make Kristin anxious about its vitality and identity. She writes, “There’s a limit to how big a farm can get without changing its nature” (126). Some readers might be surprised to learn that the Kimballs are now delivering their year-round share to New York City every week. Google Maps indicates that 283 miles separate Essex Farm from the Big Apple and that one would need four hours and forty-seven minutes to make the trip. Kimball makes clear that economics prompted this decision. In another part of the book she says that there’s “a limit to how small [a farm] can be and stay afloat, pay its taxes, its mortgage, provide a living of any sort for a family” (126).

I imagine that some purists would find fault with the Kimballs for violating the most stringent definitions of what constitutes local agriculture. I will leave the casting of such stones to those who have managed to sever all ties to the distant. I remain problematically tethered to faraway places, and so I will continue to celebrate a place like Essex Farm that generates both food that feeds people and a living for the workers, all while carefully stewarding the land itself.

Certainly, though, the Kimballs’ story does underscore a deep-seated problem. More than fourteen years after the publication of Michael Pollan’s Omnivore’s Dilemma, we remain at the beginning of our food revolution. If Kristin’s account is to be believed (and I do believe it), the Kimballs have worked with determination and persistence. They have also benefitted from good land and a few windfalls: grants, significant gifts from old friends and new neighbors, and some unexpected income from book sales. And yet the Kimballs find themselves making some difficult decisions that take them a few steps away from the ideals with which they began. Though such compromise is likely inevitable, the Kimballs’ situation suggests the existence of a systemic economic hardpan that the new wave of small, locally-oriented farms may struggle to break through. As long as they must compete with food made cheap by hidden subsidies, farms like the Kimballs’ will operate at a disadvantage. Kristin and Mark seem resolute enough for that challenge, but I hope we can continue to do more to support all those working American soil.

2 comments

Daithi+Dubh

For lack of a better way to describe this, I’ll just call it “recalibrating to reality”, to which I believe Ms. Kimball’s book appears to be a testament. In treating this subject, we often seem to rebound between romanticizing a supposedly idyllic Currier & Ives vision of our agrarian past, or go to the other extreme, regarding it in strictly – and cynically – pragmatic terms. Like a lot of folks from here in the rural South, for example, I come from a long line of farmers, but not a one of us is engaged in that work anymore; while I’ve learned a great deal from the reminisciences of my elders, I simply can’t entirely get back into their mindset, because farming was simply a reality that pervaded every aspect of their lives. I doubt there was much contemplation regarding other options.

It sounds as though Ms. Kimball, who evidently had no connection with an agrarian past, had perhaps a steeper hill to climb here. The realities of God’s Economy remain (i.e. sunlight, soil, seedtime, harvest, etc.), but the modern economy (i.e. concerning itself merely with the flow of capital, profit and loss, etc.) obscures and makes abstractions out of the former. While it wasn’t anywhere near idyllic back when our ancestors were making a living from the soil, at least they didn’t have to deal to the same degree with BigAg, the managerial state, its regulations, and the higher property taxes that are the plagues of traditional farming today.

The “recalibration to reality” I referred to above is something indivduals like Ms. Kimball, have to engage in, but it is something our entire system must get right. Perhaps the COVID crisis and the resulting threats to supply lines have begun revealing the fragility of our current conception of economy and the need for all of us, like the Kimballs – and however imperfectly – to wake up to how the world really works.

Brian D Miller

Ethan,

Thanks for sharing. I do like reading your book reviews.

However, you seem to set up an argument that brooks no alternative but your own solution. That driving 566 miles is just what small farms must do to survive, so get over it.

“I imagine that some purists would find fault with the Kimballs for violating the most stringent definitions of what constitutes local agriculture. I will leave the casting of such stones to those who have managed to sever all ties to the distant.”

I have no idea where this farm is located, being too lazy to google the distance. But I can easily imagine that there are many small towns and mid-sized cities they drive past on the way to NYC. Yes, surely, we don’t want to be purists. But if we are to foster local food sheds, local economies, local families, then we should certainly focus as farmers on bolstering the local. Let the empire take care of its own. Indeed, it always does.

Cheers,

Brian

Comments are closed.