Boise, ID. Living in the midst of a social crisis is delightfully clarifying. By delightful, I do not mean to minimize the real suffering that exists in either precedented or unprecedented times; however, it ought to be a truth universally acknowledged that a society upended is a society able to reexamine itself. And society is not upended without a myriad of individual lives being upended and thus prepared to reflect. Despite the real human suffering, I would want to remind us all that this is the nature of human life. When we are not in a national crisis or a global crisis we are yet surrounded by our own and others’ pain. A dear friend’s death, the loss of a pet, a new and terrifying diagnosis, the failure of a marriage, or merely a mechanical failure robbing us of our transportation or our formerly clean clothes all disrupt and confuse and frustrate the trajectory of our little lives. Any of these disruptions, however, is equally an individual opportunity for us to face the big questions. Who am I without my spouse? Without my health? Without my comforts? What am I supposed to be doing with my time? With my money? With my portion of creativity? What am I to say that it means to be human? To live in the world? How do I encounter others and how do I relate to them?

When these questions are forced out of the private sphere and into public conversation, a private refusal to engage becomes more and more difficult. Of course, engagement is no panacea. Hard questions about what it means to be human are no less difficult for being inescapable. Easy answers are even more appealing on a mass scale than on the individual. To engage with the question and come to a wrong conclusion is disastrous. But then, so is sleepwalking through life, anesthetized by ease and entertainment.

This delightfully clarifying year began with too much to do and too little time to do it. While I have often, very consciously, structured my family’s life in direct opposition to our cultural norm of relentless activity, I still found myself drowning under a too-common load of what seemed to be inescapable commitments. When the stay-at-home order came down, I was sick and quietly happy about a sudden cessation of commitments. Sports practices for my sons, my gym schedule, dinner engagements, the daily alarm, and the rush of my working life all fell away. And the things I love most about my life stayed: making food for my immediate family and a close friend or two, piles of books to read in my cozy little home, and long walks along the river through the beauty of this quieted city.

All of this beauty came along with the fears and anxieties of the actual crisis. I could enjoy the slower pace of life, but I could not simply enjoy it. Along with reduced commitments came concern for my friend’s health, concern for my husband’s business, concern for increased tensions in a long polarized and now seriously wounded country. Would the virus destroy already compromised lungs? Would the cabinet shop collapse under the slowed economy and then would we be able to find a way to pay our bills? Would the simmering civil unrest boil over into riots and, if so, what would that mean for my town?

Without these anxieties and fears I would not have had to ask or answer questions, but simply to relax in an extended vacation. Instead I had leisure to reexamine my life, my beliefs, and my commitments. The difference, then, between vacation and leisure is the difference between time to escape from problems and the time to contend with them at a measured pace.

Luckily, I had been preparing for this moment, perhaps unwittingly, most of my life. I moved from a childhood marked by trauma and chaos to a rooted adulthood in a series of consciously undertaken questions, answers and commitments. The tentative moves I made as a young woman, away from unstable employment and housing and toward education, career, and homeownership have been given new depth over the years by readings and studies in Plato, Berry, Tolstoy, and Austen. A sense of the world as containing limitless possibilities best pursued while honoring the constraints and limitations of the human scale is opened in these texts. Deliberate and deliberative engagement with this vision is the discipline to which I have devoted both my leisure and my professional life. That I stumbled on all of this by chance in the tiny library of Priest River, Idaho means that none of it redounds to my credit, but it still means that I was in some sense ready for the pandemic (other than that we possessed only one pack of toilet paper).

Two recent books address these same questions and the context for asking them explicitly, thoughtfully, and even lyrically. Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn’s Ars Vitae: The Fate of Inwardness and the Return of the Ancient Arts of Living is a scholarly exploration of the modern situation contrasted with the ancient arts of living. She is a gifted scholar whose examination of ancient works, their modern scholarly reception, and the appearance of big ideas in popular culture is consistently brilliant. Thoughtfully selected quotations, careful paraphrase, and incisive summary characterize her treatment of everyone from Plato, Epictetus, Plotinus, and Augustine to Foucault and Camus. Further, she is a guide with strikingly original insight into their fundamental coherence and wisdom as well as their limitations. Putting the primary texts of the major philosophical schools into conversation with popular culture as well as scholarly and popular secondary texts, Ars Vitae invites the reader to rethink modern culture, to see it as a weak remix of more coherent ways of living rather than a new or innovative social experiment.

Her study of the ancient philosophical schools is grounded in an examination of the modern malaise. Her diagnosis is quite stunningly insightful: we are new Gnostics, wrapped up in a dualism that permits any indulgence while demanding dehumanizing asceticisms and culture-destroying solipsism. Trapped in an utterly goal-less society of limitless possibilities, distracting entertainment, and disruptive movement, our inner lives are essentially non-existent. We have no inwardness. We love the therapeutic and yet we cannot become healthy. We live in a “knowingness” that dismisses learning and we are profoundly ignorant of what a good life might be. Lasch-Quinn calls the reader to explore the four main schools of ancient philosophy, reject the New Gnosticism, recognize the strengths and the limitations of these schools, and take the first step toward living not just a good life but a beautiful one. In a winning picture of the benefits of re-engaging with Platonism she calls for a pursuit of the philosophical that refuses to instrumentalize it. Learn and think and question for the sake of learning, thinking, and questioning, and we and our society will grow more human and more beautiful. Try to forcibly fix society by applying philosophy, and we will once again spiral into the solipsistic ugliness of a Gnostic narcissism.

Though a densely argued scholarly work, Lasch-Quinn’s book is lyrical in its summaries and winsome in its pronouncements. She manages to cover over two thousand years of philosophical development in under four hundred pages, and while those pages are dense in content, they are charmingly readable. The introduction, “Therapeia,” is worth the price of the book. Describing the world of capitalistic therapy, she says: “Luck, pluck, and marketing allow self-help Horatio Algers to ply their trade unchallenged. In a world of short attention spans, any kind of follow-up on the effects of the advice is nonexistent” (12). Advising individual engagement with complex wisdom she says: “We should be wary of relinquishing to someone else the post of tour guide, let alone architect, of our own inner life” (13). Cautioning over-reliance on pop psychology and “programmatic solutions” she writes: “These characteristics of the therapeutic culture, its manner of self-perpetuation, and its ultimate costs can be summed up as a loss of inwardness. . . . The therapeutic thus spells a systematic derision of the individual’s own ability to become adept at the art of living” (18). And every other page yields another insightful crystallization of the failure of our culture to provide human beings with the framework for a human-scaled and beautiful life.

The best moments in the following chapters are where Lasch-Quinn concludes her overviews of primary and secondary texts and moves to her own interpretation and evaluation of the same. Gnosticism, in its ancient and modern forms, is dispatched with a sharp critique of the ways it attempts to create ego, superiority, and disdain for the world. Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Cynicism are praised for the ways they directed adherents toward a definite telos and criticized for their failures to guard against too narrow practices that exclude some critical aspects of human life. Platonism is praised, though not unreservedly, for the way it directs our perspective out and up toward the good in a way that elevates, refines, and satisfies: “Given our separateness, all communication is translation. The reality of ignoring inwardness and failing to cultivate the inner life as our sole basis for connection makes translation impossible.” And thus we need to “[be] open to influence but impermeable to manipulation” so that we can give ourselves “to deep involvement, to the inseparable intertwining of our minds and our lives.” We must “start with acknowledging our coexistence. The irony is we think we want everyone to speak our own language. We want to feel comfortable in the world and try to surround ourselves with people like us. Communication with those like us can be harder than with those not like us because we fail to see this challenge. We are all discreet beings” (319).

Zena Hitz’s Lost in Thought is more personal than Lasch-Quinn’s, but no less grounded in the rich philosophical tradition that emphasizes thinking, questioning, and exploring. Shorter, and faster moving than Ars Vitae, Lost in Thought is an intellectual memoir rather than a scholarly work, but Hitz navigates the personal and the academic with ease. Hitz identifies the same danger Lasch-Quinn concludes with: if we pursue the intellectual with the intent of being better at business or social relations, we will destroy it. Instrumentalizing the intellectual life dehumanizes the individual, destroys culture, and robs us all of our connection to the world and our joy in it. Hitz’s narrative of her path through academia illustrates Lasch-Quinn’s thesis about the necessity of pursuing philosophy for the the love of wisdom so neatly that one might have supposed collusion.

Hitz’s life is interesting as biography and her insight into systemic issues in academia (adjunctification, depersonalization of teaching, toxic competition) is bolstered by her personal path disengaging from the tenure-track mill and first entering a convent and then returning to the intimate teaching experience at St. John’s College. She moves beyond the biographical to embed her portrait of the intellectual life in great fiction. Muriel Barberry’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog (at least the film version of it) and Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels provide a wealth of characters and situations for exploring the effect of the intellectual life on the individual. Hitz praises the private, the useless, and the lost for how these enrich the human experience and while she does praise the work of intellectuals who shaped the world, her work emphasizes how focusing on intellectual work for its own sake and releasing concern for its effect deepens the work itself and paradoxically makes it more effective. Intellectual work that “merely” changes your own life is enough. And if that is enough, then it may also change the world.

Lost in Thought is valuable for how it paints a winsome picture of the beauty of a life devoted to some intellectual pursuit. Whether it is bird-watching (The Peregrine by J.A. Baker gets special attention), or fiction writing, or obsession with the Battle of Gettysburg; whether a researcher is independently wealthy and able to devote all her time and wealth to a project, or whether a patent-office clerk is doing math on the side, or a laborer is spending a few hours a week reading to supply his mind with material for reflection; whether a poet’s work is destroyed in a fire, or read by three scholars, or popular the world over; the work of the mind can and will enrich any human life. As Hitz writes,

If human beings flourish from their inner core rather than in the realm of impact and results, then the inner work of learning is fundamental to human happiness, as far from pointless wheel spinning as are the forms of tenderness we owe our children or grandchildren. Intellectual work is a form of loving service at least as important as cooking, cleaning, or raising children; as essential as the provision of shelter, safety, or health care; as valuable as the delivery of necessary goods and services; as crucial as the administration of justice. All of these other forms of work make possible, but only possible, the fruits of human flourishing in peace and leisure: study and reflection, art and music, prayer and celebration, family and friendship, and the contemplation of the natural world.

Lasch-Quinn encourages a Platonic pursuit of beautiful truth while explicitly acknowledging that we will probably disagree over what that is. She argues that the pursuit itself is fundamentally unifying, but gives little attention to the ways that competing ideas of the true, the beautiful, and the good can set us against one another. The Greek poleis were not exactly characterized by peaceful resolution of disagreements. This is particularly concerning given her diagnosis of modern attempts at Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Cynicism as failures to identify, have, or even desire, a telos. Without ends, without goals at which to aim, our culture is uniquely adrift. To have a goal but no power is at least to know what one would aim at if they could. Anchorless but also directionless, wind and windlessness both become equally meaningless.

Hitz’s Catholicism, naturally, provides her with a clear telos, yet she still makes apparent the ecumenical openness of the intellectual life. She, along with Lasch-Quinn, argues that the practice of the intellectual life is open to anyone regardless of belief, social status, or even ability. Thinking about the ultimate questions is what defines our humanity. If we abandon these questions, we abandon something foundational in our nature. If we pursue these questions, however weakly or poorly we manage the process, we are at least acknowledging what it is that makes us human. And if we cultivate that, we work toward the humane even if it is a small step in a long journey.

The art of living is always an urgent question. Asking what it means to be human is foundational to building an individual life as much as building a society. When one set of distractions is destroyed by a change in our living conditions—as when we can no longer work, or shop, or dine out because of a pandemic—we can pick up another set of distractions—like a Disney+ subscription or a premium PornHub account (two real things that rapidly expanded throughout the world in March and April)—or we can reexamine where we focus our energies. The limitations imposed by the pandemic have deepened my sense that a well-balanced life is one that is lived in close connection to a very small group of people. That I can and should spend much of my precious allotment of time observing, tending, and loving plants, animals, and people. It deepened my gratitude for my personal library (it was great to have essentially limitless reading options) and the space to garden a bit. And Lasch-Quinn and Hitz have deepened my belief that reading my books and writing my ideas and my stories are worth doing whether they affect anyone other than myself today or tomorrow or ever. The art of living well includes conscious reflection on the art of living well and both of these books will help you do it. Read either one, and you will go forth more absorbed, more thoughtful, and probably a bit more absent-minded in the best sense.

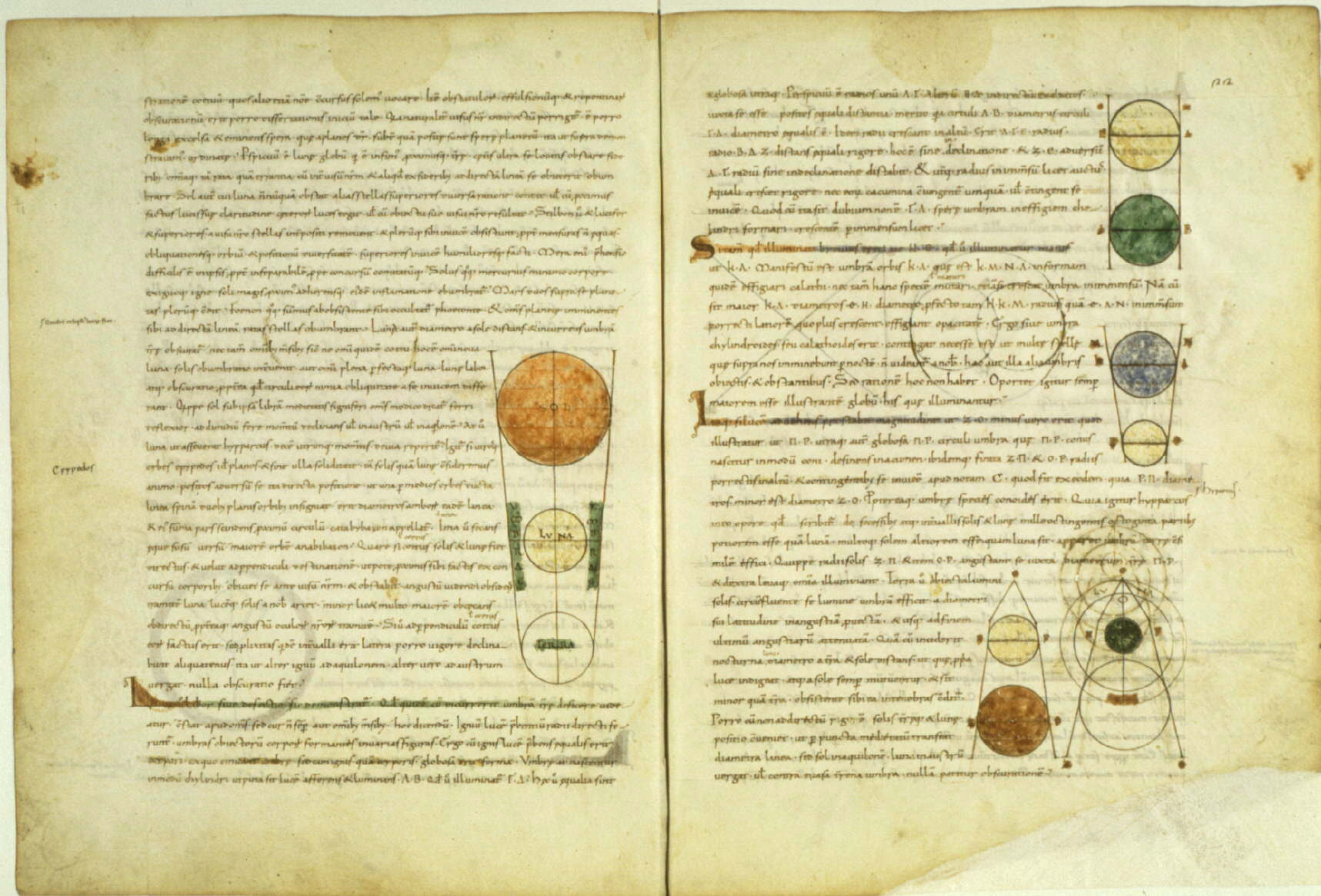

Image credit: Calcidius’s Latin translation of Plato’s Timaeus.

1 comment

Andrew G Van Sant

Have you read Josef Piper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture?

Comments are closed.