Waco, TX. First things first. Ron Howard’s adaptation of Hillbilly Elegy, J.D. Vance’s bestselling and contentious 2016 memoir, has its problems: the acting could be better, the lines are sometimes poorly scripted, the characters appear like caricatures of real people, and the plot meanders to and fro which, combined with Hans Zimmer’s soundtrack and slow-motion montages and flashbacks, forms a story that is uneven and sentimental. But the truth is that life is often poorly scripted, its actors could be better, its characters are often caricatures of real people, and its plot meanders into a story that is uneven and sentimental. Elegy is uneven in such a way that it resembles life, and it does not deserve the wave of criticism it has received. The fact that it has may owe more to a prevailing distaste for life than it does to the film itself.

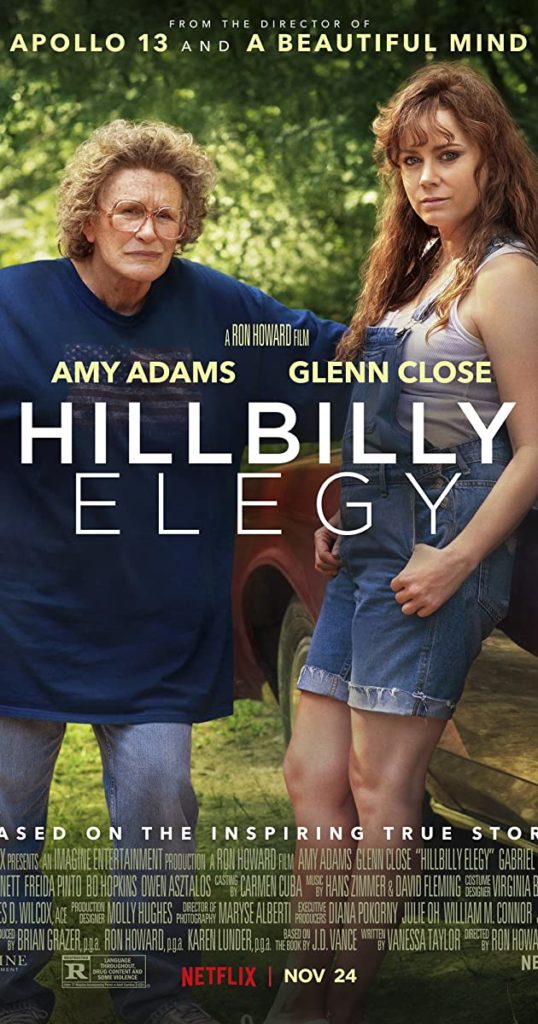

J.D. (Owen Asztalos) is a boy who shuffles from home to home in Ohio as his mother Bev (Amy Adams) struggles with addiction and abuse and his Mamaw (Glenn Close) tries to care for him and his sister (Haley Bennett). He is a pale, chubby, klutzy, and naturally smart kid who does not fit in a place that doesn’t have one for the likes of him. It is a triumph of a portrayal of a kid who is good at some things and terribly awkward at most others, someone who might make a good adult but is terrible at being a teenager. Like many such people, J.D. channels his dysfunction into the hard work of finding a place for himself, which will in time lead him to the Marine Corps, a fast-track degree at Ohio State, and eventually Yale Law School. (There are no spoilers here, as the film plays as a collage of timelines that bounce back and forth.) But he must live and learn among the other kinds of dysfunctionals who do not succeed as he does, his kith and kin. As the story progresses, J.D. takes many turns for the worse before he gets better, and his mother takes many more for the worst, while his Mamaw strives hard to mend these tangled lives. Family histories are unveiled, cycles repeat, and a family hits walls and keeps running alongside them in desperate search for doors.

Many critics have complained that Elegy is apolitical. But it seems no accident that Howard juxtaposes an idyllic beginning—strong, loving grandfathers and uncles protecting a child, great-grandmothers sitting on the porch listening to an archaically eloquent country radio preacher defend the life of his people, a steel mill steaming along—with views of fighting couples, boarded-up apartments, dying towns, and hints of drugs and unhealthy sex. The cinematography does not preach, since it does not offer any direct answer to these woes, but it does frame the notion that there is something quite different in this America today from two generations ago, and all these characters and landscapes are feeling that something, or someone, somewhere, is missing.

Hannah Arendt held that forgiveness is one of the two bases of politics, for without forgiveness man is doomed to live under the shadow of mistakes he can never amend. This is a film of people failing and being forgiven and failing again, struggling to act after they have sinned or have suffered the sins of others. Howard’s script repeats key themes that come across as ham-fisted but ring true nonetheless. Each of the four main characters owns a scene in which he or she must bear the weight of the word responsibility and must struggle with the paradox that one must be responsible in the very moment that one can’t. And this causes them to break down and cry out, Who will speak for me? Who will be responsible for me? At its best, this is a film crying out for grace and forgiveness to a silent God. Its single quotation of Scripture haunts the entire film: “Now we see through a glass darkly…”

For Arendt, the other basis of politics is the promise, the act in which man, in the midst of all the fluctuations of life, stakes himself to a concrete future in covenant with other men. Broken promises appear throughout this story, and they take their toll on J.D. Where this film might be weakest is its conclusion, which (without giving spoilers) was directed in such a way that it came across as more cheerful than it actually was. J.D. (now played by Gabriel Basso) must choose between the priorities of his own life and the immediate care of his suffering mother, and whichever choice he makes, he cannot choose perfectly. He cannot bear total responsibility, he cannot speak for everyone, and, in that moment, he cannot live up to the promise he embodies as the caretaker for his family. Contrary to critics’ claims, this story, as a kaleidoscope of memories and hard decisions, is no straightforward can-do tale—even if Howard comes dangerously close to portraying it as such at times.

Hillbilly Elegy is indeed political, but in a deeper sense, entangled as it is in the webs of broken promises and repeated forgiveness. In the repetition of promise and forgiveness, this family inches its way towards small graces, and by the ending credits, it suggests that promises may be renewed in the future. But within this cycle, can there be a greater grace than that which we fickle human beings give to each other? Will we find that something, that someone, that somewhere we feel like we once had? Or should we content ourselves with the small graces, the hard work, the incomplete victories that do not fix the past? I left Hillbilly Elegy with both a deep yearning for something more and also a chastened sense that less must do until then—the imperfect story, family, and country, the imperfect human words of promise and forgiveness.