Below is the introductory essay to the new issue of Local Culture, which is devoted to regional writers and artists. If you subscribe by March 1, you’ll receive this issue in your mailbox. You can whet your appetite by perusing the complete table of contents.

I stood there a little out of range, and I thought, It is all still new to me. I have lived my life on the prairie and a line of oak trees can still astonish me.

—Marilynne Robinson, Gilead

The provincial has no mind of his own; he does not trust what his eyes see until he has heard what the metropolis—towards which his eyes are turned—has to say on any subject. This runs through all activities. The parochial mentality on the other hand is never in any doubt about the social and artistic validity of his parish… All great civilizations are based on parochialism—Greek, Israelite, English.

—Patrick Kavanagh, Collected Pruse

The thing about a city skyline is that it’s a skyline only if you’re looking at it from somewhere else. There is no skyline visible at the base of the Willis (née Sears) Tower, nor at the base of One World Trade Center. Indeed, the very sky that these structures impudently “scrape” is barely visible. What you mostly see—aside from the great mass of men avoiding eye contact one with the other—are significant monuments of arrogance that can make even arrogant men feel monumentally insignificant. Small wonder, then, that concerning the City that Never Sleeps a patriot of Dixie once crooned, “all I’ve seen so far is one big hassle.”

To each his own. Let that charitable sentiment be used liberally. Let it extend even to your tired, your poor, your huddled insomniacs.

Of course to the one-armed intrepid John Wesley Powell looking up from the Colorado River the sky might have seemed “nothing more than a single clear blue line” (so sang a folk band from the Ozark Mountains), and there are valleys aplenty that limit the range of vision from whatever basecamp or ground-zero a body might be standing on. But the thing about an open space far removed from the penumbras of Babel is that it has no need to flatter itself with talk of skylines. From within and without alike it affords you a view of itself; it extends an invitation for you to know it intimately. Proximity does not diminish its allure. And as your vision sweeps a rise or a hillside or a gorge, your imagination follows along, moving in sympathy with the mysteries beyond. The mystery beyond the Willis is the Hancock—until Lake Michigan imposes its impertinent natural limit upon the metastasis.

Let no one think that this is a screed against cities. It isn’t. We’ve been told of old that, properly understood and rendered, the city is the place of human flourishing; it affords us the opportunity to know ourselves and our limits—to know, that is, what sort of creatures we are. But as Thomas Merton once remarked—and herein lies the problem—the hierophants and salesmen of the age would have us believe that “only the city is real”—the city that by now is a far cry from the polis the Stagirite was at pains to recommend, and certainly not the thing in whose peace Jeremiah said we would find our own. Can a political animal fashioned after the trinal unity find no other locus amoenus than the industrial megalopolis with all its self-approving arts so jealously adored by the omnibenevolent elites toiling away in the selfless labor of Explaining Things?

And are only the arts of the city real? Or can anyone be surprised that, as power and wealth contract and centralize, such a prejudice should manifest itself in the arts? Is only the life of the busy and bustling place, the place of mergers and acquisitions, worthy of story and song and canvas? It is one thing that artists should congregate in Ben Jonson’s or Dr. Johnson’s London, or in Hawthorne’s Concord, or in Hughes’s Harlem. That is reasonable enough. It is another thing that Sarah Orne Jewett’s South Berwick should suffer the sneers of “regionalism” for not being Gertrude Stein’s Paris. Apparently it is better to be a boozing expatriate of the lost generation, loitering about Shakespeare & Company and writing in cafes, than to be N.C. Wyeth, brush in hand, comfortably at home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where it is impossible to get lost.

Let us pause at Chadds Ford, where the southwest painter, Peter Hurd, successfully undertook two very sensible projects: instruction from N.C. Wyeth and the courtship of his daughter Henriette. Hurd once told Gene Logsdon, the contrary farmer from Upper Sandusky, Ohio, that N.C. or “Pa Wyeth” was the key to understanding the artwork of both Hurd and Wyeth fils—the great Andrew Wyeth. “He gave us our realistic approach, so-called,” Hurd said, “and he gave us our respect for the so-called regional, finding greatness or beauty in the near at hand.” Perhaps it was for the benefit of the feted paint splatterers and the droppers of crucifixes into jars of urine that he added, “the avant-garde in art circles reject what they call realism in my work and Andy’s too. They like to say I am a square. I am not a square; I am a cube. A cube has six sides. That’s five more than the avant-garde have. I can view the world from any one of those facets. They have one view. And most of that is put-on.”

That is from Logsdon’s The Mother of All Arts: Agrarianism and the Creative Impulse. I account it yet another sorrow among many that Logsdon has left us for the silent majority. You can hardly doubt that the author of such books as Holy Shit! Managing Manure to Save Mankind and You Can Go Home Again would have made a memorable contribution to this issue of Local Culture.

What of this issue? It was originally slated to coincide with the 2020 meeting of the Front Porch Republic at Middle Tennessee State University. The topic had been set (The Arts of Region and Place) and the speakers lined up, including, in the keynote slot, Scott Russell Sanders, a Tennessean by birth but a longtime and firmly-placed Hoosier whose books include the aptly titled Staying Put. His latest, The Way of Imagination, had just been brought out by Jack Shoemaker and the good folks at Counterpoint Press.

But by March there was already widespread suspicion that the year itself had been born under an unhappy star. Our nation’s most important annual ritual, the NCAA Basketball Tournament, had been cancelled, and others would soon suffer a similar fate, among them the ceremonial commencements that unleash upon the world credentialed and debt-strapped graduates duly prepared to go anywhere but home. An old throw-back called Transcendentalism seemed to some as if it might be staging a comeback, for vapor locks began to show up in individual minds everywhere, as if descending from a vapor-locked Over-Soul. Elites were securing their own livelihoods and causing “background” people to lose theirs. “We’re going to follow the science,” said the universal technocratic We, even though the science was already on a zig-zag voyage of a hundred tacks. When Dottie’s Diner and Art’s Bar at last began to go broke gradually, then suddenly, it would prove to be a great convenience to the experts that science was on hand to take the blame. And you could see a growing realization in the eyes of even the most timorous undecided sophomore for whom future job security had become a pressing concern: maybe I should change my major to Expertise—or at least pick up a minor in it.

At any rate, whether from the dictates of Expertise or the common prudence of those who know their own mortality, Murfreesboro would be closed off to those who fain would travel thither in search of the free associations that characterized a once-grand political experiment in a now-perishing Republic. Thus do the best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft-agley.

But herein LC presses on, taking up in its small way the arts of region and place, maugre the times and their distempers. Hollywood will fling its Teufelsdröckh, and Madison Avenue will find a way to sell it. To each his dröckh. Let people nevertheless make music together. Let the musicians of the country’s many sections play their own tunes to the beats of their own drums. Let the crossroads conceive and bring forth another Booth Tarkington. Let the Hawkeye State give us more Grant Woods, the Bluegrass State another Irvin Cobb, the Land of Sky-Blue Waters Jon Hasslers not in single spies but in battalions. Let the children of River City scratch out their approximations of the Minuet in G. Let the sons and daughters of the Republic, whether in Clifton or Pigeon Forge, whether along the Big Blackfoot or beside the Big Two-Hearted, whether in the Big Easy or even in the Big Apple, all learn to see and to cherish the near at hand. And may a line of familiar oak trees never cease to astonish them.

For when the Ernest Gaineses of Pointe Coupee Parish and the Vachel Lindsays of Springfield and the Eudora Weltys of Jackson pick up their pens, when artists everywhere take to canvas and score, to script and clay, to pencil and paper and woodshop and kiln, you know there still remains a democracy of invention betokening a vibrant and colorful citizenry and giving both voice and hope to anyone poised to enact one of the most useful offices of citizenship: the office of making, from somewhere rather than from anywhere, the arts that sanctify a place, that acknowledge and articulate its meaning, that render it durable because loveable, and remind us of its lovely enduring worth. The wonks of the major news outlets may carve the nation into two colors, red and blue, and thereby lay down the unbearable lightness of nuance, but children in an art class can tell you that by mixing red and blue you can get a third color. And lo! there are still others on the palette. What portraits, what landscapes are possible with so much color at hand—dare I say with so much diversity at hand?

Now it is doubtful that even a country with vibrant regional arts, arts unique to each place and composed of all the colors on the palette, can do much to cure every form of myopia that afflicts it. But when an electorate surrenders its thinking to the wonks and neglects the example of its children, to say nothing of the arts that help those children enter into the fullness of their humanity, that electorate may soon follow the experts into darkness. Thus will the lately-sighted also descend into blindness, there to be led by the long-since blind. Soon a kind of Manichaean idiocy prevails; soon red and blue become black and white, and the line between good and evil no longer cuts through every human heart but between Massachusetts and Montana, between the eye of Newt and toe of Mitt, right on down the aisles of parliaments and houses and senates. What a relief! Why think when you can just move a line? Sheep to the left of it, goats to the right (or clowns and jokers, if you prefer). And then let no man come to be our judge.

But what if vibrant regional arts are in fact a kind of leaven to the nation’s lump of lifeless dough, an antidote to the poison of a far-reaching and mind-numbing monoculture? Wouldn’t failing to defend local and regional life and all its many artifacts put the dough at risk of never rising? Must children take their tuition in curricula written from afar and not by those who might tell the children where they are? Must Dottie’s always give way to Denny’s and Art’s to Applebee’s? The local summer Jubilee in my little town, with its arts and crafts and music and beer tents, always features a demolition derby, which a native son named Tommy almost always wins. Those who think us deplorable for this are welcome to sip their lattes and stare at their screens and avoid contact with other humanoids as they think such borrowed thoughts. We grant them that. We propose to deny them nothing. We ask only to determine how we shall live here—imperfectly, certainly, but in accordance with memory and custom and local lore, mindful of our own dead and dying and young and yet unborn.

Not that there aren’t attendant dangers to the “regional,” especially if it is not properly developed and properly guarded. It is doubtful, in the first place, that a dispersive art alone, although desirable, can do the work of cultural cohesion, especially if there is no broader will to regard that art in the aggregate and to situate it in a larger cultural context. This business of cultural cohesion is a wicket of considerable stickiness, and we in the West, certainly we in America and undoubtedly others elsewhere, are working through a problem that no one concerned with comity and legitimacy should take lightly, namely, whether a civilization can survive without a common culture, by which I mean a cultural inheritance of long memory in education, literature, art, history, music, political theory, civic-mindedness, and so on. A rehearsal of cultural illiteracy is probably not necessary here, and I am not speaking of illiteracy in such basics as reading and writing, though I might. Both are as evident as the darkness of a long winter’s night. I mean the question of whether a polity can remain viably stable and coherent when Moses and Homer are unknown or have no more authority than a skateboarding graffitist for whom Roger and Francis Bacon are interchangeable brands of breakfast meat. I admit that breakfast meat does link the generations in a palpable way, but men do not live by bacon alone. The stories and histories we know are the stories and histories that in the telling and hearing we are known by, and by which we come to know ourselves and our places, whether local, regional, or otherwise; we and they are part of a larger fund of memory, instruction, and example that the local and regional are features but not the sum of. Part of that fund is young and local, but much of it, the greater part, is old and universal. We have our pledges of allegiance and anthems and symbols, our declarations and constitutions and bills of rights, holidays and days of remembrance, oaths of office, basketball tournaments, and truths held to be self-evident, to say nothing of our martyrs to those truths. But we also have—or had better have—famous funeral orations and the great codes of the lawgivers, epics and confessions and dialogues, Summas in theology and theses numbering in the nineties, soliloquies and sonnets and the speech on St. Crispin’s day.

But what happens when Bright Lights, Big City (or, what is worse, Sex and the City) replaces Winthrop’s City Upon a Hill in the collective consciousness, or when jollity and gloom can no longer contend for an empire, as at the Maypole of Merry Mount, because self-reliance and ressentiment are now at loggerheads among welders and wonks alike? And how much worse that there’s scarcely a college president in sight who can take a stand for Winthrop and gloom and self-reliance—or recognize ressentiment when he sees it circling his once-venerable institution? We may soon have answers we don’t like. This, I trust, is not a point that needs belaboring. How often were the children of Israel told to remember, and how often were they chastened when they didn’t? And yet, by now, what is there for us to remember? The Alamo Bowl from last year? Who even remembers the children of Israel? Again: it is doubtful that a dispersive art alone, although desirable, can do the work of cultural cohesion, and such substitutes as American Idol, Oprah’s Book Club, and Karen’s Kar-Pool Blog don’t seem to be working very well so far.

It is doubtful, in the second place, that in the absence of the long remembered artifacts of the cultural tradition there will be any way to judge those newly added, and this must necessarily include the arts of region and place. Even as we credit the art by which a given place is fixed in memory, we must continue to vex ourselves with questions of excellence and form—unless of course we have no qualms about living by the worst that’s been thought and said. And make no mistake: once the long-remembered becomes the long-forgotten, the new, lacking the tutelage and measure of the old, will not merely be new; it will also be deficient at best and bad at worst. Anyone looking for a good galvanized bucket these days knows that. Any student sitting at a desk made of plastic and pressed particleboard should know that. So another problem confronting the loyal regionalist is the matter of criticism rightly conducted. Booth Tarkington, aforementioned, was once far more popular than his fellow Hoosier Theodore Dreiser, but today we remember Dreiser and not Tarkington. On what grounds? Is it on sound formal principles that we judge Dreiser to be more worthy of our attention? Is it because only the city and its arts are real? (Is it because Dreiser was more traveled, or a better philanderer, or that his jowls were bigger?) Failure to ask these questions is worse than punting on third down just because you’re backed up to your own one-yard line.

We can no more be uninterested in the question of what is good, and whether a thing answers to its form (or to its material, efficient, and final causes), than we can be indifferent to whether a two-legged chair made of balsa wood will answer to our need for sitting down, or whether a clay jug with a hole in it will answer to our noble custom of making mash in the hollers of the hills. The question of whether a thing is good insofar as it answers to its form does not go away simply because we may or may not believe that the arts should flourish in all their regions and places, much less because artists and critics alike have ceased to care about form at all, or have lost the ability to recognize it, or, what is worse, have abandoned the proper order of things—learn first to see, then to understand, and then to love—for the easy uncritical shortcut of noticing and liking, which is not love at all but the mere tickling of fancies. If we applied such laziness to gustatory matters, who would ever venture beyond cold gruel and boiled beef? It is the larger cultural context, the cultural remainders, the treasury of something better than the worst that’s been thought and said, that make possible our addressing the problem of what is good. If we do not engage in the serious business of criticism made possible by the long-remembered, we are not far from being unhelpfully indiscriminate about the Handmaid’s and the Winter’s tales, which are both good but not equal, or about The Georgics and “Georgia on My Mind,” again both good but not equal. The local or regional, though valuable as such, may (and in many instances almost certainly will) fall short by other standards. Again: in the absence of tradition and the judgments it alone makes possible—supposing it has the requisite heirs who are worthy of it—there is a danger of valuing the regional and local without regard for their formal merits.

The first two dangers have concerned (1) the cultural and civic limitations of the here and now and (2) the problem of formal or aesthetic judgment. But wouldn’t both disappear if we simply dropped our affection for, or even patience with, the regional and then capitulated to the pronouncements of our Rightful Superiors in The Center? Isn’t a liking for the regional a mere prejudice of place anyway? And so I come now to the third danger.

It is doubtful, in the third place, that localists or loyal regionalists are immune to the allure or can escape the accusations of a falsifying prejudice. Wendell Berry once remarked that there is a regionalism “based upon pride, which behaves like nationalism” and also a regionalism “based upon condescension, which specializes in the quaint and the eccentric and the picturesque.” Abuse can rush in where imagination fails to tread, for the road to falsification is paved with bad inventions; and a “false mythology,” Berry warned, “tends to impose false literary or cultural generalizations upon false geographical generalizations.” Soon only the region is real. Soon “regional pieties” blind us to the complexities and particularities of our whereabouts, putting in their place the ringless cipher of an abstraction. For his part Berry said “the regionalism that I adhere to could be defined simply as local life aware of itself. It would tend to substitute for the myths and stereotypes of a region a particular knowledge of the life of the place one lives in and intends to continue to live in.” He went on to insist that such a regionalism troubles itself with living before it troubles itself with art, and “the motive of such regionalism is the awareness that local life is intricately dependent, for its quality but also for its continuance, upon local knowledge”:

Without a complex knowledge of one’s place, and without the faithfulness to one’s place on which such knowledge depends, it is inevitable that the place will be used carelessly, and eventually destroyed. Without such knowledge and faithfulness, moreover, the culture of a country will be superficial and decorative, functional only insofar as it may be a symbol of prestige, the affectation of an elite or “in” group. And so I look upon the sort of regionalism that I am talking about not just as a recurrent literary phenomenon, but as a necessity of civilization and of survival.

These remarks from the 1970s (A Continuous Harmony) serve at least two important purposes, one to act as a safeguard against the uncritical chauvinism to which anyone might be prone, whether under an oak or under the Willis, and the other to remind us that our place (or region or section) is not raw material; it does not exist so that proprietors can simply mine it, whether for economic or artistic purposes. It is, rather, and in the first place, “a necessity of civilization and survival,” irreducibly itself, rendered heritable by our knowledge of it, our care and affection for it, and the arts and artifacts that memorialize it.

These and much else compose not “an abstract system,” as John Crowe Ransom said, “but a culture, the whole way in which we live, act, think, and feel.” This is a “genuine humanism,” he said, “a kind of imaginatively balanced life lived out in a definite social tradition.” It is “deeply founded” in a “way of life itself—in its tables, chairs, portraits, festivals, laws, marriage customs.” That such local richness is under attack from the flattening tendencies of an expanding monoculture can hardly be doubted. But must the cube of Chadds Ford always be reduced to the square who stands before a Campbell’s Soup can, amazed in scripted fashion at its profundity? Aside from this genuine humanism, this “imaginatively balanced life lived out in a definite social tradition,” what other armature is available to those who would defend, from the many forms of predation, all that they hold dear?

As for this whole bundle of concerns or “attendant dangers,” as I have called them, consider Ransom once again: “We cannot recover our native humanism by adopting some standard of taste that is critical enough to question the contemporary arts but not critical enough to question the social and economic life which is their ground.”

And so I ask again, then, whether the arts of region and place can in fact be a kind of leaven to the nation’s lump of inert dough and whether failing to defend local and regional life and all its many artifacts wouldn’t be tantamount to killing the yeast. It is too much to ask of the arts that they save us, especially if they themselves have forsaken beauty for such shibboleths as “originality.” There was never a poem or a painting that doubled as a dying god. But if we render each place with the affection and care that artistry requires, we can at least sleep easy knowing that we haven’t subtracted from the vulnerable funds of affection and care—multiplied them, much rather, kneading and punching down and rolling out a living thing irrepressibly rising by the leaven of a properly developed and properly guarded regional and local motive.

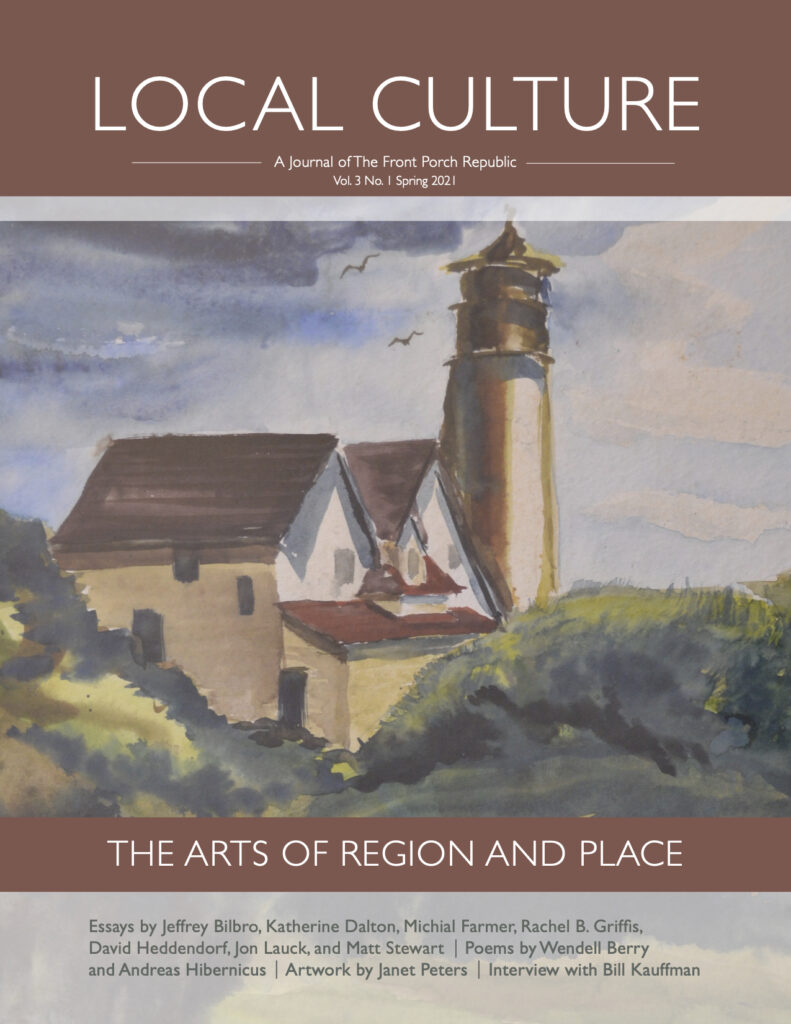

LC features the artwork of iconographer and retired art teacher, Janet Peters, who lives in Williamston, Michigan (born 1936 in Scottville, Michigan, home of the famous Scottville Clown Band). On the cover is her watercolor of the Point Iroquois Lighthouse on Lake Superior not far from where the Edmund Fitzgerald (of a certain celebrated ballad) sank off Whitefish Bay on November 10, 1975, just 104 years after the birth of Winston Churchill, the once-popular American novelist from St. Louis, Missouri. (NB: November 10 is also the expiration date of the American painter John Trumbull [1843], the Rifleman Chuck Connors [1992], the Beaver State’s Ken Kesey [2001], and failed decentralist and anti-flouridationist Norman Mailer [2007]).

LC is once again set in Eric Gill’s Perpetua. In the queue: issues devoted to Sir Roger Scruton, failures in higher education, and, when the time is ripe, a retrospective on 2020. Thanks for reading and subscribing.

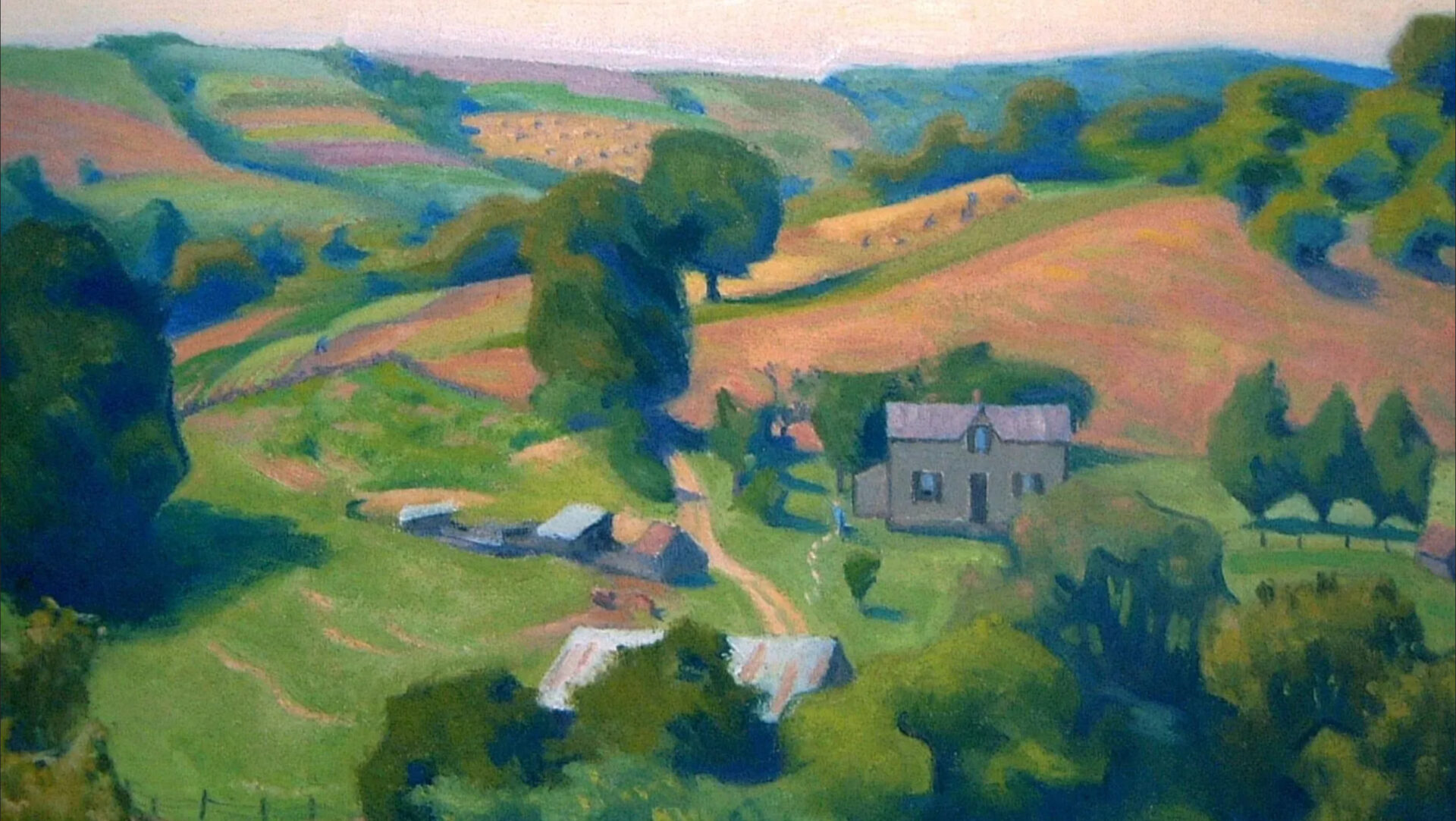

The header painting is “Summer, 1934” by Harlan Hubbard.

5 comments

dave

Well done, short in print! Funny how that goes. Enjoyed the issue. Thanks again for the work.

dave

Print copy of Local Culture came today, same day as my Main-Travelled Roads book from Belt publishing, among others. Good day! Just easier for me to read paper, seems like.

dave

You know Ms Dalton, agree with you. Odd thing for me is it’s hard to imagine Van Gogh without Arles, or put Rembrandt in sunny Italy; Monet had his garden, Toulouse-Lautrec could have only been in Paris. Could be a long list. I don’t know that Jewett is any more provincial than Proust. Or Joyce. Happen to like Pollock, Professor. Don’t know that I have an explanation for it. Closest I can think is a real letter, the odd way it can collapse or transcend time for the writer and reader. Anyway, not the thing. The thing is, watched the recorded zoom thing and enjoyed it, thanks, but stumbled over your claim Ms Dalton to Bill Kaufman , that you didn’t have a hat. If I remember, you’ve written once or more about the derby, I thought you must have a hat. How can you not have a hat? What an odd thing for someone from KY to claim.

As far as the talk, was thinking what’s gone is American pragmatism, and wondering if your group would make it around to something along those lines. Not what something means but whether it works. Thinking a consequence of moving from a manufacturing economy to a service economy or something else entirely, I don’t know. Anyway, appreciate all the work, glad you all are still around. That’s enough for now, planting soon, patch of spinach and peas. Weather gets odder all the time, hard to time it right. Will try again soon to navigate your vast and archaic vocabulary, Professor. Fain to.

Kate Dalton

Nice piece, Dr. Peters. Eye of Newt I will adopt for my own use, thank you, and yes, all of us with children in school are putting up a daily fight against their being asked to read and then live by the worst that has been thought and said. I will be recycling that as well.

I suppose “regional art” is art that is deemed good enough to be of interest the people of that region but not good enough to be worth the time of a national or international audience. In any other sense, all art is regional in that it is made by someone somewhere, no matter how deracinated the maker or how far-flung the subject. Some are perched and some rooted.

But if one major reason to read books (or experience other kinds of art) is to try to understand the world and vision of a mind other than our own, then giving Mr. Berry’s fine novel Jayber Crow a one-paragraph sidebar review, as I recall a major taste-making paper did, or pegging Jewett’s unbelievably good Country of the Pointed Firs as a regional and hence minor gem, is to dismiss these works-of-rural-place as outside the possible topics of interest to a self-styled serious critic. To such a critic Turkey is, literally, less foreign, more likely to have been visited and of more casual interest than Kentucky, much less Kentucky of a few generations back (I will grant such a critic has probably vacationed in coastal Maine). And it is that utter lack of curiosity, that lack of possibility of any human sympathy, that is ultimately so culturally divisive.

dave

I didn’t make it past fain. I suppose I fain, or am always faining- got lost contemplating. Not even a word, I suppose. Came to, skipped ahead and seemed I might only be half the way through and thought maybe it’s a William Morris you’ll want to keep an eye out for. What is for use not display, well wrought. For the daily round, to attend with grace despite the long shadow, leavens not what we own but what we enjoy with something transcendent. Art, here, must always be particular. Anyway, appreciate the work as always, hope my subscription is current. Will make a second attempt some time in the coming days.

Comments are closed.