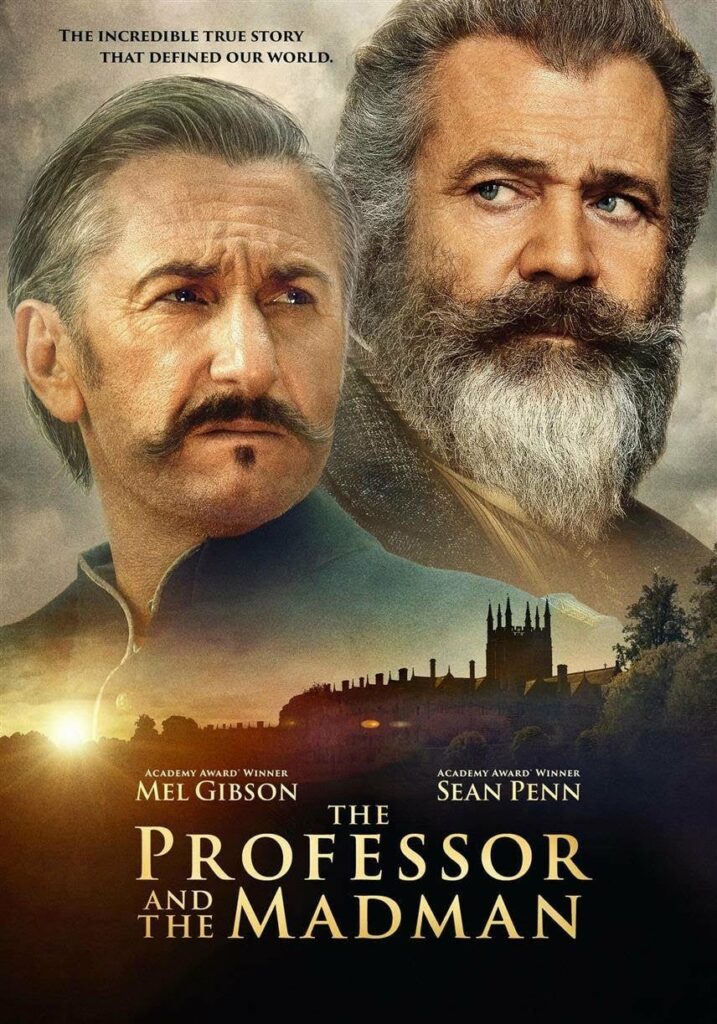

West Palm Beach, FL. The Professor and the Madman is a film about the Oxford English Dictionary based on real people and events. Opening in the late 1800s, it follows the efforts of James Murray, a Scottish autodidact, to put the dictionary together and account for every English word and its history. In this herculean task, Murray finds unexpected help and friendship, from a man imprisoned in the asylum at Broadmoor. William Chester Minor, a retired U.S. Civil War surgeon, is confined to that hospital because his madness drove him to murder an innocent man. It may seem as though a movie about the Oxford English Dictionary, which opens in the 1870s and closes in 1910, would be nothing but a period piece. In fact, it is a very timely film, because it deals with the enduring issues of justice and forgiveness.

The film opens with William Minor’s crime: shooting a man in cold blood. Though he was declared not guilty by reason of insanity, his guilt was clear—to many in the public and also to himself. The death of Minor’s victim created a vacuum: a now-struggling, working-class family without husband or father. Society has imprisoned Minor, but justice is more than punishment. Throughout the film, he wonders how he can forget the things he’s done and how he can atone.

We live in a society more than capable of identifying misdeeds, both minor and serious, social and criminal. Thanks in part to the long memory and long arm of the internet, nearly anything said or done in the past can be held against someone. Almost every week some person in a position of celebrity or authority apologizes for some recently-discovered misdeed, and even obscure people face serious consequences for words amplified by the internet. Words and deeds that may have once had small or local consequences now seem to follow someone forever. People have opportunities rescinded; they can lose jobs and, sometimes, friendships.

The public reaction to this new reality is schizophrenic, as can be seen in the conversations around “cancel culture.” For the most part, the distinction between “being canceled” and “facing consequences” is only a matter of perspective. Some of the same people who chanted “lock her up” at Trump rallies believe that cancel culture is out of control because Gina Carano was fired from the Mandalorian due to her political tweets or because Marjorie Taylor Green was stripped of committee assignments in Congress. On both ends of the political spectrum, second chances tend to be reserved for fellow travelers.

While we seek to publicly punish people for things deemed inappropriate, as a nation we are also imprisoning over a million people for criminal activity. In 2019, 419 of every 100,000 US residents were in state or federal prison. Despite the fact that these figures are in decline, our incarceration rate is still much higher than other developed countries. And people can linger in prison for anything from murder to struggling to make bail. Once released, those who were convicted of felonies struggle to reassimilate to society: they find it hard to get employment with a prison record, they are prohibited from voting in many states, and they are, increasingly, burdened by fees (some totally unrelated to crimes).

Our society may sometimes be divided on how to define right and wrong, but that has not dampened enthusiasm for identifying wrongdoing. There may be no consensus on the existence of original sin, but nearly everyone believes we live in a world warped by the flaws and faults of others. We all believe the other drivers on the road are the dangerous ones.

Even apart from our individual misdeeds, society itself seems tainted. In the eighteenth century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau theorized that society had a corrupting influence on individuals. In the twentieth century, Sigmund Freud, and later Norman O. Brown, agreed. They believed that society itself was sick, making us all neurotic. Later in the twentieth century, people talked less about neurosis, but more about global wages and how our habits of buying and spending could help or harm others. Today people are asking about “systemic injustice.” Our modern society makes us complicit in many things. But it is not so easy to run from society or to solve all of our problems through psychoanalysis. Localism can be one way to avoid unnecessary entanglement in things we do not understand or support, but a localism strict enough to keep us completely untainted would be hard to sustain in a world that pulses with connected markets. How do we address the harm we may be doing, sometimes unwittingly or seemingly unavoidably? Too often we simply opt for denial.

In The Professor and the Madman, Minor’s crime results in his confinement. But his imprisonment does little to help the family of his victim, who find themselves desperate to survive. His crime has also distanced him from others socially. Minor’s work on the dictionary leads Murray to establish a friendship with him, but that association is one that some in Murray’s life find unsavory (and which may jeopardize Murray’s employment). Minor himself is tormented by his guilt. In the film and in life, the combination of guilt and delusion lead him to self-mutilation.

We know the road to perdition, we all walk it. Is there a road to redemption, to restoration? This is one of the animating questions of the film and of our times. So much hinges on our ability or inability to answer this question. We can think of consequences, and cancelation, as exile from the fellowship of community. If we can find no way back, we will continue to deny wrongdoing among our friends and allies while damning our enemies. Once a wrong is admitted, a person is condemned forever. This creates a hell for our opponents and leads to such open hypocrisy in our own camps that cynicism seems justified. When we look around our society now, we see that those whose sins are known often cannot find a path to restoration, and thus it is all too easy to fall into recidivism or embrace relativism and retreat deeper into the echo chamber of their own place on the political spectrum. That is disastrous for individual humans and divisive for our society.

What is the way back from wrongdoing? In The Professor and the Madman, it includes restorative justice. Minor has a pension from his time in the U.S. Army. He gives much of his money to support the family of the man he murdered, saving them from penury. When he learns that Eliza, the widow of his victim, cannot read, he establishes a friendship with her and teaches her to read during her visits to him. He cannot make up for the loss of her husband, but he can do much to ameliorate her condition. Minor seeks to atone for his wrongdoing. Minor also needs to be restored by others. He is offered forgiveness and acceptance, first by Murray and then by Eliza. He wins the affection of many who monitor him in the asylum. (There is more to say here about Minor’s plot, but it would include spoilers.)

In The Professor and the Madman, the way forward from wrongdoing includes restitution and forgiveness. Though he is insane, Minor does not deny or excuse his crimes. Nor does he put off the responsibility of caring for his victim’s family. But those around him do not treat him as irredeemable; they recognize his contrition and respond with forgiveness and acceptance. Murray does not withhold friendship from him, though it is to his professional disadvantage to be connected to a murderer and though, in the film, his wife is skeptical of their association. Neither does Eliza, the widow, withhold forgiveness when she sees that Minor’s repentance is genuine and his efforts at restoration are also sincere. By the end of the film, Murray and Eliza are united in believing that Minor has suffered enough for his crime and deserves better treatment than what he received at Broadmoor. Murray is moved enough to take Minor’s case to the government.

The path to restoration in The Professor and the Madman is shaped by an understanding of the Christian faith. Murray, a devout Christian, sees more to Minor than his crimes because of his belief in the imago dei. And he is willing to befriend and even advocate for Minor because of his belief that all people are dependent on God’s grace and mercy. Theists may have some advantage in walking the path of restorative justice because their traditions include the concept of sin and ways to remedy it, but one need not be a theist to understand the importance of being able to both identify and resolve wrongdoing.

The Professor and the Madman presents two key practices that we can consider when we ask how we can work toward restorative justice in our twenty-first century society. The first is the acknowledgement of wrongdoing and the necessity of repentance. Where there is denial of wrongdoing, especially in the face of evidence, there can be no road back. Where there is acceptance of responsibility and confession of sin, there must be a way back. That way is often made through the practice of forgiveness, which asks something of the offended.

An excellent example for what restoration can look like and what it is up against is the life of Michael Vick. In 2007, when he was a star quarterback in the NFL, he went to prison for his involvement in dogfighting. His crime made him one of the most-hated athletes in America. His poor choices also cost him his wealth. But, as told in ESPN’s 30 for 30 about him, Vick made significant decisions about how to address his misdeeds. He pled guilty and served 21 months in prison. When he filed for bankruptcy, he did not choose to escape his debts. Vick was open to accountability. He was willing to face the consequences of his crime. When he left prison, he came back into the league, initially as a backup.

Vick’s return to the league was controversial. People protested. Some thought he should never play again. A vocal minority believes he should still be in prison. The issue hinged on forgiveness. That was so clear that the Washington Post opened its article about Vick’s ESPN special with this line: “You don’t have to forgive Michael Vick for dogfighting, but ESPN wants you to understand the context.” Did Vick deserve a second chance? He could do all the work of atonement: prison, debt repayment, and ongoing work with the Humane Society. But without forgiveness, Michael Vick would never be more than his crimes, and he would be denied an opportunity to be restored to society.

Atonement is hard and unpleasant work. It is so difficult to admit wrongdoing that many people seem unable to do it. Everyone has experienced a “fake apology.” It is also unpleasant to go to prison, or to step down from a leadership position, or to compensate someone else for our wrongdoing, or to lose opportunities as a result of our words or actions. Similarly, it is hard to see people we like sidelined for their poor choices. Parents sometimes try to shield their children from consequences. Friends often refuse to be informants.

For those who have been harmed by others’ misdeeds, forgiveness is also hard and unpleasant work. In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin wrote to his nephew who was growing up in a Harlem Baldwin compared to Dickensian London. Baldwin told him that most of white America wouldn’t ever be able to acknowledge, or be willing to consider, how bad existence could be for the people of Harlem and how oppressive racism was. And Baldwin wrote about how acceptance and integration were kind of a joke if you considered the contrast between the ideals and actions of white society: “There is no reason for you to try to become like white people and there is no basis whatever for their impertinent assumption that they must accept you. The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.” Our society cannot experience restoration unless we do it together. Forgiveness is often required, even though it is not free.

The Professor and the Madman can be an important film, whether or not we completely accept its solutions, if we let it lead us to the important conversation of how to acknowledge and address wrongdoing. How many of our gritty screen dramas that expose the darkness of our world even attempt to shed light on how we can move beyond the long shadows of our sins into the light of reconciliation? We need more stories that can make us think through how to, as W.H. Auden wrote, “love your crooked neighbor / With your crooked heart.” Another contemporary cultural voice which can contribute to this work is the podcast Ear Hustle, a non-fiction podcast that explores life in San Quentin prison. Always interesting, it is often powerful. Its episode “Dirty Water” features participants in a restorative justice project meeting and talking, in this case sex trafficking survivors and offenders. Ear Hustle is an excellent reminder that our decisions about how to handle wrongdoing have far-reaching ramifications in many individual lives.

In our society, we have a desperate need for both the recognition of wrong and the restoration of forgiveness. Our is a world with hateful middle schoolers, madmen, and murderers, all mixed in among newborns, neighbors, and next-of-kin. The longer we live the more opportunities we have for mistakes, social and criminal. As we continue to call out wrongdoing and we continue to imprison millions of Americans, we must consider how to make consequences restorative rather than simply retributive. Such changes would not just benefit our friends and family who are kicked out of carpools or incarcerated; it would improve the health of our whole society. The Professor and the Madman can help us start the conversation about what restorative justice should look like in our communities.

1 comment

Martin

This is perhaps the best FPR piece I’ve read all year. It identifies and juxtaposes two current issues with a clear call for moral contemplation and action.

The quote from James Baldwin reminds me of a statement presented by a black woman 22 years ago to her fellow clergy at a Unitarian General Assembly:

https://revthandeka.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Why_Anti-Racism_Will_Fail.pdf

I am grateful to Prof. Stice for her essay and hope to see similar appeals without waiting another two decades for courageous people to step forward.

Comments are closed.