Tulsa, OK. Censorship breeds thought. It causes us to question, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. I wasn’t entirely surprised then to hear a student’s reaction as I pulled Huck Finn from the shelf.

“I heard Twain was a racist.”

I promptly asked if he had read any Mark Twain.

“Nope.”

I confess I was tempted to say, “Do you let other people decide what you think?”

It would have been a lively debate in a high school classroom. But rather than argue or say more about Twain’s life, I said, “Let’s read the whole novel before you decide.”

Thinking isn’t an end but a beginning, a beginning that is much like Huck’s own journey. In The Adventures of Tom Sawyer we know Huck is a follower by nature. But in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck is beginning to change, or should I say, beginning to think.

That doesn’t mean he’s some ideologue, however. Huck is no hero, though he is clearly a child on the cusp of adulthood. As in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Huck and Tom’s imaginary childhood adventures quickly become real. From pranking the ever-suspicious Jim at night to signing contracts in blood with their gang, Huck Finn begins as Tom’s story did. Their youth sparks the adventure, yet I think Twain manipulates their adolescence, especially Huck’s, to deepen his story.

Adolescence often hinges on thinking—or not.

At first, our empathy is stirred by Huck’s lack of education and careless upbringing. Pap Finn is a mean drunk. When he first appears in Huck’s room in the widow’s house, he discourages Huck from taking on airs by becoming educated, that “highfalutin’ foolishness.” We could argue that Pap censors Huck by limiting what he reads or limiting reading entirely. Twain intentionally provokes our pity, and that’s before Pap kidnaps, beats, and terrorizes Huck. This is not an adventure, yet Huck doesn’t seem marred by it at all. No bitter bad boy here, Huck longs to be free of Pap and those who want to “sivilize” him. But is Huck’s longing for freedom the same as thinking?

In an ironic twist, Huck came to mind last month as I read about Arkansas courts and their affirmation that prison inmates have the right to access books and information under the First Amendment. Huck too was a prisoner. He too lacked education and access.

In this case, the sheriff’s book ban in the Benton County jail appears to be a natural consequence. It wasn’t about limiting access and education. It was about the physical misuse of books—using them to cover vents and plug toilets. The ACLU, however, argued that prison officials were “engaging in ‘content-based censorship’” because the prison still allowed religious texts, but not other material. While the ACLU couched their complaint in terms of censorship, the real issue seems to be one of access.

Yet the word “censorship” continues to be thrown around, and it often refers to very different kinds of efforts to forestall reading books and responding thoughtfully to them. I’m reminded of author Jeanine Cummins and the controversy over Macmillan’s American Dirt a year ago. Could a white author write authentically about a fictional immigrant experience? Should she be allowed to?

Despite mixed reviews, it became clear Cummins could write a thriller, though members of the Hispanic community criticized her stereotypes, language, and her slight connection to her Puerto Rican heritage. One Macmillan employee said, “The problem wasn’t necessarily that she wasn’t Mexican—the problem was that we published the book in a way that we said defined Mexicans.” Macmillan publicly acknowledged they made mistakes, especially in overstating Cummins’ heritage, the migrant experience, and their overall lack of sensitivity. Regardless, American Dirt remains a bestseller today, a full year later. Readers identified with the story, and the controversy boosted sales, much like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

I’m still wondering why any publishing house thinks this type of situation is new. Do readers get to decide for themselves, or have they been conditioned to believe a book should be labeled and judged by someone else, as my student did?

Twain encountered these questions regularly. In the Reconstruction Era, he deigned to write about race and class issues and often used regional dialect and crude vernacular in polite society. On March 18, 1885, The New York Herald published a report from the public library committee in Concord, Massachusetts:

One of the Library Committee, while not prepared to hazard the opinion that the book is “absolutely immoral in its tone,” does not hesitate to declare that to him “it seems to contain but very little humor.” Another committeeman perused the volume with great care and discovered that it was “couched in the language of a rough, ignorant dialect” and that “all through its pages there is a systematic use of bad grammar and an employment of inelegant expressions.” The third member voted the book “flippant” and “trash of the veriest sort.” They all united in the verdict that “it deals with a series of experiences that are certainly not elevating,” and voted that it could not be tolerated in the public library.

Twain’s response published in The Hartford Courant on April 4 is well-known. He was grateful for the committee’s public censure and “generous action” because they doubled his book sales. Their protest “will cause the purchasers of the book to read it, out of curiosity, instead of merely intending to do so, after the usual way of the world and library committees; and then they will discover, to my great advantage and their own indignant disappointment, that there is nothing objectionable in the book after all.”

Again, in 1905, the Brooklyn Public Library removed all copies of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer due to “coarseness, deceitfulness and mischievous practices.” The two novels made the move from the children’s reading room to the adult section.

In the last two months, books have been pulled from circulation for differing views on transgenderism, for exposing antifa, and even for being too old or too historical. Who determines our access to these books, to all books? Are we not allowed to choose who or what we read under the First Amendment? Maybe the ACLU’s broad understanding of censorship gets at an important reality: denying access is a species of censorship.

How, then, can I ask my students to read a novel like Huck Finn and invite them to go about drawing their own conclusions?

Twain himself was pondering the American conscience and society’s shifting morals through the 19th century. Once Huck fakes his death and determines to live on Jackson’s Island again as he did with Tom, Huck encounters the widow’s slave Jim who has run away. From here, Huck’s story accelerates into his very own, replete with lessons and failings.

From quickly realizing his stupidity when he pranked Jim with a dead snake to the adventure of boarding the sinking steamboat simply because of the romantic danger of scavenging, Twain provides readers with glimpses into Huck’s burgeoning awareness—“Now was the first time that I begun to worry about the men—I reckon I hadn’t time to before. I begun to think how dreadful it was, even for murderers, to be in such a fix.”

What empathy is this? Huck thinks of others, even murderers, as fellow men at the point of death. I still wonder if it’s because of his experiences with his father. The point is that Huck is changing, and perhaps America was too.

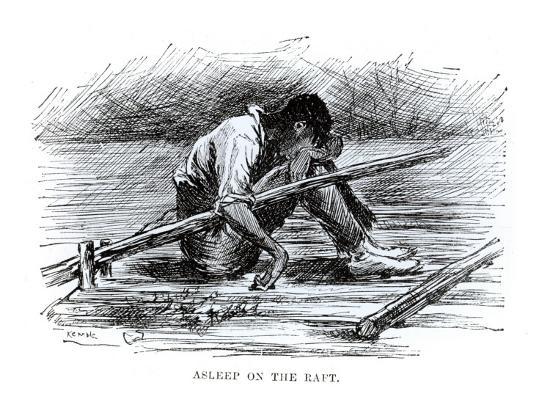

Soon after, Huck and Jim are separated in a dense night fog. Once Huck finds Jim asleep on the raft the next day, Jim is overjoyed to see Huck alive. In a cruel twist, Huck chooses to tell a whopper. He tricks Jim by pretending that Jim dreamed up their entire separation. After the snake incident, I can’t imagine why Huck thinks this is some amusing prank. It’s a moral step backwards, and my students see it and groan. Nevertheless Jim goes along with it and weaves Huck a fanciful story of his dream, turning the fog and danger of the night before into an allegory of their journey to freedom.

But then Jim notices the leaves and branches on the raft. After Jim explains his heart “wuz mos’ broke bekase you wuz los,” he confronts Huck with the truth—that Huck lied to him and made him feel ashamed. Huck, however, doesn’t lie again to get out of it. Filled with remorse, Huck humbles himself to a slave because he just now realized, as he will continue to do, that Jim is human.

By the next chapter, Huck is tested again. Huck and Jim hope they have reached Cairo, Illinois, where Jim can be free and work to buy his family back. Jim is so excited and praises Huck, “you’s de bes’ fren’ Jim’s ever had; en you’s de only fren’ old Jim’s got now.” Huck is sick to his stomach because he knows he would obey the law and turn Jim in as a runaway. He accepts slavery as his culture did. He believes that helping Jim run away is a sin. Yet that sickening in his stomach, that troubling in his heart, is telling.

Huck is in a world of trouble, and Twain depicts his conundrum beautifully—“It would all get around, that Huck Finn helped a [n-word] get his freedom; and if I was to ever see anybody from that town again, I’d be ready to get down and lick his boots for shame.” The moral climax of the novel lands here as Huck debates whether to send Miss Watson a letter detailing Jim’s whereabouts. Finally, Huck says, “All right, then, I’ll go to hell,” whereupon he tears the letter up. Huck has begun to think through what to believe, what to do, and most importantly, what to value. Crucially, he is now thinking with his friend Jim and pushing against the moral standards of his society.

But Twain isn’t done. Huck must rescue Jim from the Phelps’ farm just as Tom reappears in the story. This is the crux. Who actually changes? What type of American will change? Are we Toms or Hucks? Yes, Huckleberry Finn is a coming-of-age tale, it’s a social criticism and satire, it’s a commentary on the South and slavery and racism, but my favorite element is that the novel chronicles how Huck grows past Tom.

The Tom of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is fun-loving, just dangerous enough, and one heck of a dynamic leader. But he doesn’t change, and I’m not sure he thinks things through. What’s more, he doesn’t realize Huck has changed. We know by the end that he has manipulated Huck since he knew all along that Jim had been freed. My students often say the appearance of Tom at the end ruins the novel because Huck regresses and is submissive to Tom and his splendid plans. A pertinent theory, yet more importantly, I think, Twain is reiterating that Huck is imperfect. He is still learning, and I don’t have to explain that to a single student.

When we find out that Jim has already been freed and that Pap Finn is dead, we realize, along with Huck and Jim, that they have been running away from nothing. Nothing. Their long adventure seems pointless now.

Yet if their journey didn’t free Jim from slavery, it may have freed Huck from his unthinking acceptance of his culture’s racism. If Huck has grown in tenderness, in mercy, and in justice, how much more has his character deepened because he now views Jim as both friend and fellow man. The censorship of slavery no longer dictates Huck’s morality. Unlike Tom, Huck has begun to question his society’s standards, to weigh and consider what is just and right, and I hope that by reading this story, my students may follow him in this difficult endeavor. If my students are constrained by labels and systems, then they have succumbed to censorship. My hope is that through Huck and Jim, my students will glimpse a more charitable way of thinking.