Puyallup, WA. In his 1970 book Cities of the Prairie: The Metropolitan Frontier and American Politics, political scientist Daniel Elazar pointed to “the very real paradox of American life (and perhaps of modern life generally); high social and geographic mobility prevents the formation of traditional communities based on stable populations, while functioning, self-perpetuating local communities clearly do exist and may be even more powerful politically than in premodern times.”

In other words, we Americans move around a lot, but somehow or other we manage to form and sustain decent, livable, and influential communities.

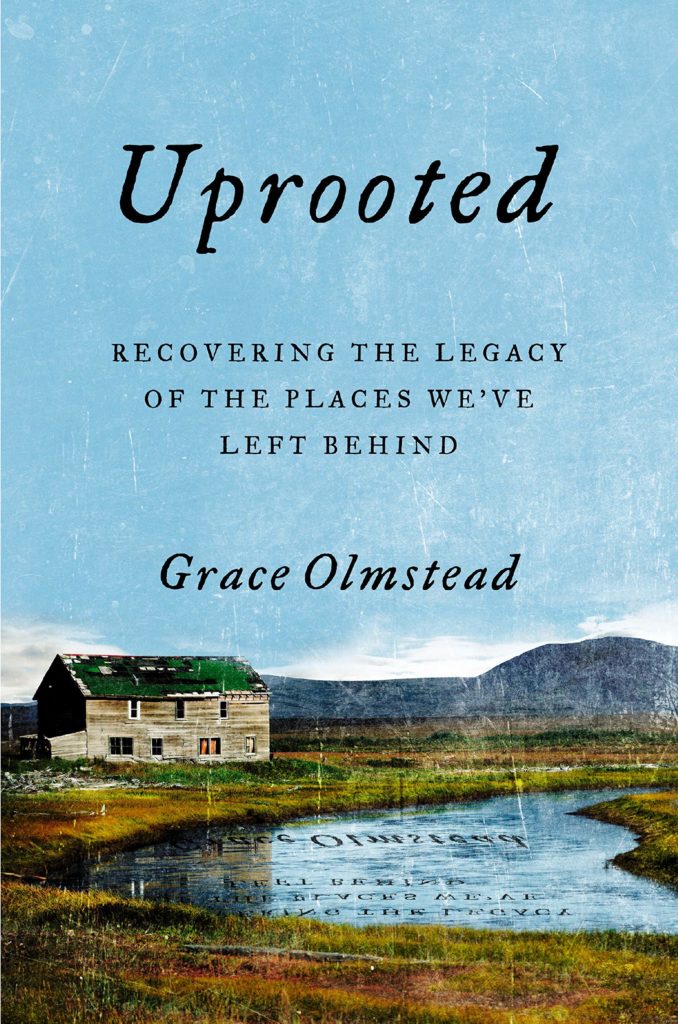

I came across this insight from Elazar while reflecting on Grace Olmstead’s important and beautifully-written new book Uprooted: Recovering the Legacy of the Places We’ve Left Behind. Uprooted is a history of Olmstead’s family roots in the farming community of Emmett, Idaho, a documentary of the changing landscape of American agriculture, and a deeply personal contemplation on the meaning of home as Olmstead weighs whether to return to Idaho or remain in Virginia. It seems that Olmstead’s book has sparked a much-needed conversation about community, mobility, the local impacts of economic centralization, and the importance of family commitment to places.

It is worth considering Elazar’s “paradox” in this context. Elazar suggested that local attachments can form and flourish even in a mobile society. He observed that the American pattern of community formation and indeed our covenant as a people differ in important ways from those of traditional European societies. “Local ties are the primary ties even for the mobile people of the mass society,” he wrote. “It is clear that, in the United States, they are not and cannot be the ties of a gemeinschaft, the rooted, homogeneous, organic community of medieval Europe. Rather, they must be based on the realities of a contractual civil society—social and geographic mobility, pluralism, and voluntarism.”

Just as Alexis de Tocqueville suggested in Democracy in America that marriage and family in democratic America center more on affection than on obligation, we might also suppose that our impulse to be part of a community arises more from affection than from obligation.

To the French-American Nobel Prize winning biologist Rene Dubos, mobility and choice served a useful function as a search for genuine community. In 1977, he addressed the Human Ecology Conference in New York City on an “extraordinary social trend—for the first time in human history a large and increasing number of people can select their place of residence” instead of simply living obligatorily in the same place as one’s ancestors. At the same time that human beings were becoming more mobile, they were also becoming more interested in communities, he believed. Dubos declared that “the most interesting and powerful force in our time is that people are getting more and more interested in regional and local affairs.” He believed that this trend toward intentional localism would persist with the continuing increase of mobility, along with changing energy sources, food demands, and environmental pressures that would refocus Americans’ attention on local concerns.

Of course, mobility is not an option for everyone. Urban studies theorist Richard Florida’s construct in his book Who’s Your City, which Olmstead cites, includes three groups of Americans: the “mobile,” the “rooted,” and the “stuck,” who face economic barriers to social and geographic mobility.

While acknowledging the realities and limitations of mobility, Olmstead presents an eloquent defense of genuine rootedness. She notes that American transience “has birthed a nation filled with innovation and incredible success stories. . . . But it’s only when people decide to stay that a place can develop.”

The choice to commit to a place, whether in staying, returning, or arriving for the first time, is one of the profound life choices we can make. And it’s worth noting that the choice to live in a place is a different thing from growing up there, or remaining there on account of economic immobility.

In his 1968 essay, “A Native Hill,” Wendell Berry described his journey back to Kentucky. After working in New York, he realized, “I still had a deep love for the place I had been born in, and liked the idea of going back to be part of it again.” Upon returning, he reflected, “I had made a significant change in my relation to the place: before, it had been mine by coincidence or accident; now it was mine by choice.” Having made this choice, Berry wrote:

I began to see the place with a new clarity and a new understanding and a new seriousness. Before coming back I had been willing to allow the possibility—which one of my friends insisted on—that I already knew the land as well as I ever would. But now I began to see the real abundance and richness of it….I listened to the talk of my kinsmen and neighbors as I never had done, alert to their knowledge of the place, and to the qualities and energies of their speech. I began more seriously to learn the names of things—the wild plants and animals, the natural processes, the local places—and to articulate my observations and memories. My language increased and strengthened, and sent my mind into the place like a live root system.

In this way, we should not discount the power of intention.

There may be intentional reasons not to stay in a place, as Olmstead acknowledges. This does not diminish the real loss that occurs when people leave a place. “But why we leave and what we cultivate once we’ve moved to new ground are important questions to consider,” she writes.

The important thing is to create and sustain conditions in which people can form commitments like those Olmstead observed among the farmers of Emmett, Idaho, where “the bonds of life they cultivated in their lifetime were thick and nourishing.” Once we have committed to a place, then our sense of obligation grows.

If Elazar was correct about the “very real paradox of American life,” we should never take our roots for granted (for it is all too easy to do so), nor should we doubt our ability to take part in meaningful community wherever we land. There is power in human intention, and regardless of where we find our home in the landscape of American life, we can do our part as friends, family members, and neighbors.

Looking ahead, Daniel Elazar was emphatic that a “renewed sense of localism” was essential to America’s future. For Americans, this means renewed intentionality about our local communities, not merely living in one place for a sustained period of time.

As Olmstead puts it, “Wherever we decide to live, we must learn to stick: choosing to invest ourselves in place, to love our neighbors, to leave our soil a little healthier than it was when we arrived. Every place will be imperfect. Our own efforts at living well in place will be imperfect. But love suggests that we ought to keep trying anyway: to keep sowing seeds of service and generosity in the lands we love.” This is a statement about intentionality, one that we would do well to take to heart in our own ways and in our own places.