Atlanta, GA. The idea of a lost Paradise abounds in world mythology. Historian of religions Mircea Eliade wrote at length of the “prestige of origins”— glorious beginnings after which something went seriously wrong cosmically or humanly. Paradise Lost American-style has often involved a supposed decline from the communal solidarity and “values” once prevalent in rural villages and small towns, the culprits being urbanization and industrialism.

Vernon Parrington, in Main Currents in American Thought (1954), described the pastoral vision of the small town as a scene of “economic well-being, neither cursed by poverty nor corrupted by wealth, where communal solidarity and friendship prevail, . . . where American democracy resides, dominated by the spirit of equality, according to which men are measured by their innate qualities”—and where, one might add, was never heard a discouraging word, and the children are all above average.

Cultural anthropologist Robert Lynd and his wife Helen in Middletown (1927) were concerned that the widespread transformation of American socio-economic arrangements after 1890 had vitiated the solid old Anglo-Saxon, Protestant communities of the Midwest. In the 1920s, the Lynds had launched studies of Muncie, Indiana, a mid-sized Midwestern city, believing the older American social virtues had probably survived there and that Muncie-Middletown might serve as a model of social excellence for the new, more various and sprawling industrial-urban America.

Unfortunately, Lynd and his wife were to discover, as Arthur Vidich writes, that the putative solidarity of the old America town had been compromised as completely in Muncie as elsewhere by “competitive individualism and pecuniary standards of civic worth”; and “the members of the community were no longer each other’s moral keeper.”

The romance of the American village or small town lingered well into the twentieth century, though, and still resonates, if more dimly. People being social by nature, given to relationships, and dependent on them practically, generally like to think of themselves as members of communities, and this may seem easier in compact settings, amid limited populations, than in large cities. Whether life in a small American town was ever essentially more “communal” than life elsewhere is at least questionable, though. The force of natural social predisposition, combined with cozy-seeming appearances, can generate ambiguities—if not delusions.

Working summers between college terms in the 1950s as an apprentice reporter for the daily newspaper in my Ohio hometown (population eight thousand) I was aware of how often the term “community” cropped up in its pages. Each day’s edition included a “Community Calendar.” There were articles on “community meetings,” and “community celebrations,” reports on baseball games at “Community Field.” Representing our town as a “community” had no doubt encouraged contributions to what was then known as the “Community Chest” (later the United Fund).

Community-this, community-that.

What people did in our town mainly, though, was what Americans everywhere did, or aspired to do: they went to work, paid their bills, had hobbies and private circles of friends, sent their kids to school, and sat in front of screens and speakers. Confronted with some emergency requiring cooperative effort, they’d pitch in—maybe relish the novelty of doing so—but that wasn’t what life generally required of them. What the term “community” bandied in my hometown paper referred to most obviously was simply people gathered for the pursuit of economic ends.

At my desk in the newsroom one day, I’d just run across some reference to “the community” in copy I was reading, when it occurred to me that perhaps the newspaper was the community. Paperboys rolled the community into a tight little projectile they winged onto your porch every afternoon. It was a local commonplace that there was “never anything in the paper,” but there were subscribers who became very agitated when this nothing failed to arrive in a timely fashion.

When the media today speak of “the Afro-American community,” the “arts community,” etc., they use the term “community” in the same way my hometown paper did. In metro Atlanta, the sprawling agglomeration of six million people where I now live, mention of the “Atlanta community” calls to mind an image of thousands of people seated in private cars idle on jammed freeways, talking into cell phones. (Rousseau in The Social Contract spoke of a similarly questionable use of language in which “city” and “town” became synonyms. “City,” he pointed out, was cognate with “citizenship” and “civility”—people working together for common ends. “Houses make a town, but citizens a city.”)

People talk about the “sense of community,” a pleasing if evanescent state of fellow-feeling aroused, perhaps, by disaster-inspired cooperative efforts, crowds at sporting events or concerts, protest demonstrations, or “social media.” Lately, the political ideology associated with the red states may conjure the sense of community. Someone has remarked that what may explain the gravitations of Americans out of cities and suburbs back to the old American towns in recent times (notably in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine) are simply the communal overtones of quaint Main Streets and squares.

Rhetoric, imageries, and special situations requiring cooperation can stir the instincts for relationship without having much connection with ordinary life and relationships generated by economic arrangements, whose effects, as we know, are often atomistic and unjust.

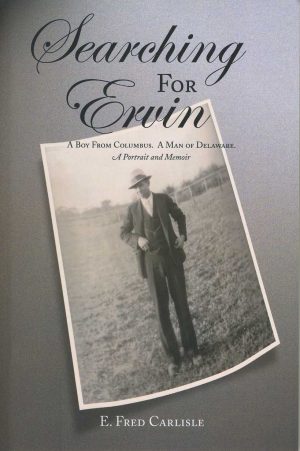

A splendid little book Searching for Ervin (Middle River Press, 2006) embodies the ambiguities in the idea of “community” in America. The book has special interest for me personally because its author, Fred Carlisle, was a youthful contemporary of mine in small town Ohio.

Fred, a few years ahead of me in school, was a bright, spirited fellow: our high school’s student body president, an all-league standout in basketball and baseball, an actor in school plays, etc. Like many in our generation, he took advantage of the expanded opportunities for education and employment in postwar America. These led almost inevitably out of our town into the greater world, and he eventually became a college professor, literary scholar, and provost of a large state university.

Searching for Ervin, a work of his retirement, is a “portrait and memoir” of his father Ervin Carlisle and an attempt to understand him better than he had in youth. Fred had “gone beyond” his father in the approved American way, but he describes himself at the end of Searching for Ervin as a “noticeably diminished version” of his father.

Not everyone would agree, I imagine, but what Fred had found lacking in his own adult experience had been the communal richness of his father’s, the complex web of relationships Ervin spun around himself, “his generosity and concern for other people (for all others), his good will, his great capacity to enjoy life, his playfulness, his organizational and leadership talent.”

Ervin had “valued others and cared for them in remarkable ways—far beyond my capacity and beyond anyone’s I know.”

Ervin had been a teacher, coach, and high school principal in our town before the difficulties of supporting a growing family on a public-school salary drove him regrettably out of education into the insurance business. During the Depression and World War II years—hard times in our town, Delaware, Ohio, as everywhere—volunteers often had to shoulder responsibilities that would later fall to governments and social service agencies. “Community service” was an esteemed virtue, and Ervin was a community servant extraordinaire. During the war he served as interim superintendent of the local public school system and assistant coordinator of the local wartime food-rationing program. He promoted a childcare program and bond levies for increasing school monies and chaired “fund drives” for worthy causes. His premature death at forty-six was front page news, with a five-column banner headline, in the town newspaper.

Fred sees the small town setting of the early-to-mid twentieth century as integral in his father’s humanity. Accordingly, Searching for Ervin has nearly as much to say about our town as it was then—or at least how in retrospect it seems to have been—as about his father. In describing the life of Ervin’s town, Fred is aware of the danger “of disappearing not just into the past, but into nostalgia, romance, and fantasy”; but he really does think the experiential possibilities of that place and time were superior to what was to exist later there and elsewhere in America. What had been lost most conspicuously was the possibility of a communal experience as rich as his father’s.

Ervin Carlisle attended public schools in Columbus, twenty-some miles south of our county-seat college town. At Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware, he majored in physical education. He was quarterback of the Wesleyan team that beat the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor one year, an upset nearly as stunning then as it would be now. “Football Made All the Difference” is one of Fred’s chapter titles. Ervin had embraced the persuasion often voiced in his time that amateur sports were valuable training for young men in sportsmanship, cooperative work, and competitive hutzpah. Of his father’s high school and collegiate athleticism, and later career as coach, Fred writes, “The team worked together in a cooperative and coordinated way in order to win. They were a kind of fraternity.”

After Wesleyan, Ervin became a teacher and coach at our public high school and then the principal of the school at the tender age of twenty-six. By the time he entered teaching, tax-supported public education was, of course, a well-established reality both locally and nationally, but people still needed to be convinced it was worth their money. The title of the thesis Ervin wrote for a master’s degree in education at Ohio State in 1937 reflected this: “Acquainting the People with Their Schools.” Judging from the portion of the thesis Fred quotes, its main message was the one commonly voiced in early-twentieth century American educational philosophy: the critical task of the schools was to civilize and socialize: “The first purpose of the schools is to develop courteous, considerate ladies and gentlemen who should be taught to think. . . . They should be taught to live happily as individuals and as members of a group. . . . These ladies and gentlemen should develop emotional controls, a proper sense of values, and tolerance.”

Socialization of the little barbarians, in other words.

This was a tall order for schools—one that calls to mind the poet Wordworth’s remark to Ralph Waldo Emerson that Americans were much too prone to substitute “tuition” (formal education) for “moral culture,” “social ties,” and “education of circumstances.” Of course, what Wordsworth failed to understand was that American “circumstances,” if not positively inimical to “moral culture” and “social ties,” often didn’t support them very generously either. He was right, though, in saying that to suppose schools could exert a force equal to that of “circumstances” in generating sociality was a dubious proposition. Lord knows, though, we as a people have tried—with some dubious consequences, one being the development of an educational class and bureaucracy “worse than anything since the time of Henry VIII,” as sociologist-author Paul Goodman once put it memorably.

Ervin Carlisle had been, in any case, a true believer in the American educational mythos. He loved schools and their associated organizations and teams. This had been apparent even in his youth. At South High School in Columbus, he’d flourished as a campus leader and a quarterback on the football team. To pay his way through Ohio Wesleyan in the late 1920s he caddied summers at a golf course in Columbus–and while he was at it, organized an educational program for caddies, a caddy newspaper, and a caddy baseball league. While in college, looking back to his school days in Columbus, he organized and served as president of a club for South High School athletic alumni. At Wesleyan he was the member of a social fraternity, a class president, and a campus “representative man.” When Fred, whose undergraduate degree was also from Ohio Wesleyan, joined the social fraternity of which his father had been a member, Ervin wept with joy.

Fred acknowledges that Ervin had been a fellow who would strike many people as “uninteresting and insignificant, if not the subject of satire.” He had been, after all, just “a small-town Midwestern man, a coach, a principal and superintendent in a small school system . . . a Kiwanian, active in the Boy Scouts, and so on.” But he was “a genuinely good man,” and his humanity, inseparable from his involvement in the life of the small town, is what Fred had found missing in his own experience and that of his contemporaries.

Was the experience of “community” in an Ohio town during Ervin’s lifetime fundamentally more compelling and authentic than has been possible after the post-war economic boom? Or should Ervin’s passion for organizing and social service be seen as an attempt to compensate for an actual fragility of communal life? Ervin was scarcely the only American in the earlier twentieth century for whom schools, organizations, and team play have compensated a more fundamental anomie. Sociologist Max Lerner once represented organizing and “joining” as all-American palliatives for social fragmentation; and the Lynds had noted that as Muncie-Middletown grew from a sleepy village into a mid-sized industrial city between 1890 and 1920, “organized leisure,” compensatory for the dissolutive social effects of economic developments, abounded: men’s service clubs with weekly luncheon meetings, fraternal lodges like the Elks and Moose, women’s clubs, organized athletic teams and leagues, the country club social calendar, public dances on holidays. “Organized leisure” might or might not engage citizen participation very fully, and it might amount to just symbolic assurance that the “community” was still there, like the American flag at Fort McHenry after the bombardment by the British navy.

When I was in high school, two men who ran a retail photo supply business in our town organized a camera club, the Shutterbugs. A teenage photography geek, I became a “charter member.” The first meeting was to be in a classroom at the high school. Arriving a bit late, I found the classroom door shut. I opened it. The scene in the room was startling: the overhead lights were off and candles burned on a table in the center of the room. The Shutterbugs gathered in a circle around the table were holding hands, while Earlene Babcock intoned a solemn mumbo-jumbo bearing on the high purposes Shutterbug membership was evidently to entail. After that came a “responsive reading”—something right out of church litany. Earlene would read a portentous statement, and then the Shutterbugs, reading from mimeographed handouts as best they could in the dim light, mumbled solemn replies. Earlene had evidently cribbed an initiation ritual from the rigmaroles of the Elks or the Daughters of the Eastern Star. Shadowy faces of several male Shutterbugs lit by candlelight from below revealed losing battles against levity.

Fred speculates at one point that an exceptionally lonely childhood may have had something to do with his father’s passion for organizing, team play, and social service. His mother had died shortly after his birth. His father, a machinist in Columbus, moved to West Virginia where he remarried, and there were vague family stories about Ervin having been mistreated by his stepmother. The task of raising Ervin had fallen mainly to his German immigrant grandparents in south Columbus, Ohio, where, as a boy, to help make family ends meet, Ervin had risen at four AM to load bread delivery trucks before going off to school.

If Ervin, in his commitments to public schooling, team play, and organizing was addressing a vulnerability in American life generally, was he also compensating for his personal past, trying to create a community ab nihilo for himself as well as the town?

I had only one personal, up-close encounter with Ervin. One day, when I was maybe ten years old, I burst through the front door of my parents’ home into the living room where Ervin and my father were discussing insurance. I’d disturbed the business at hand obviously, but Ervin paused to register my presence and beam my way the rather shy smile he displayed also in the photograph of him that appeared in the local newspaper. He gave off a quiet radiance, and his smile said he wanted you to like him.

Fred writes that his father, as educator and social servant, had been “striving, I believe, to make a life, a community and schools, of sincerity, honesty, and integrity, of caring and concern”—a task that would obviously have seemed most urgent when nothing of the sort could be presupposed. He sought, Fred writes, to create “a full, rich life not only for himself, but for family, friends, and townspeople. We all benefited.”

There is, though, at least an ambiguity, if not a contradiction, when on the same page from which the passage just quoted is taken, Fred refers to the “self-sufficient and communal” town of Ervin and his fellows. I mean, was it “communal,” or was that something Ervin, like other Americans given to “organized leisure,” were struggling to create by conscious and willful means, to offset a public life whose tendency was so often amoral and acommunal?

2 comments

Rob G

“I mean, was it “communal,” or was that something Ervin, like other Americans given to “organized leisure,” were struggling to create by conscious and willful means, to offset a public life whose tendency was so often amoral and acommunal?”

In my experience it seems to have been something of both, in that the organizational aspect was often working with pieces that themselves were more “organic” in nature. I grew up in the 60s in a small town that’s a suburb of a large midwestern city, but which nevertheless had its own character, its own small main street and business district, etc. At that time it was considered a bit too far from the city proper to be a “bedroom community,” although it has since become one.

The organic pieces of the whole were simply “there” — who knew how or when they had arisen? The woman’s sewing club that my mother was a member of, for example. At the time I remember it it was made up mostly of younger mothers, although a few older women did take part. Did these women create this idea on their own or was it something passed down from older women in the neighborhood? I have no idea. But there it was, one patch in the quilt of the larger community.

Community life is, or at least was, replete with such “patches.” The idea that creation of organized leisure comes by conscious and willful means is accurate, I think, but it might be seen, to continue the metaphor, more as a patchwork quilt than a thing created out of whole cloth.

There’s also an element of preservation present in the “conscious and willful means.” You get the sense that many people felt that these old ways were under attack, or at least threatened by lack of interest and attention. The increased organization can be seen as way of resisting those threats.

Colin Gillette

“I mean, was it “communal,” or was that something Ervin, like other Americans given to “organized leisure,” were struggling to create by conscious and willful means, to offset a public life whose tendency was so often amoral and acommunal?”

This is a good question. Running things through the filters of my often own romanticized rural life, is “organized leisure” nothing more than recreation, or the act of “recreating” as the Latin origins of the word implies? Is community the means by which we preserve the best of ourselves in service to one another? It begs to question, also, how to differentiate between the eulogized version of time past, and whether or not there are actual rules for human relationships beyond those agreed upon between participants.

Living in the rural area of Northern Illinois, along the rust belt, it is easy to notice, at times, how industry swept in, stripped the mine, and left everyone wandering around an empty cave. The greatest resource, the people themselves, sometimes seem a little lost. Yet there are still softball games, routine volunteerism, and dedication to the community, as it were, ballasting hope against an often bleak allegory of loss.

I’ve been reading Front Porch Republic for a while, and it has helped to squelch a lot of the cynicism that rises as a result of some of the otherwise bleak aspects of rust belt rural life. I will say, regrettably, the time period you speak in this piece was littered with strong elements of segregation and role conformity among the genders. Perhaps it might be easier to have “organized leisure” when there is agreement between the participants about the rules, whether spoken or unspoken.

Finding a route to a more inclusive community takes writing new rules, and as a result, dissonance resonates through the generational divides. It may be true that public life is amoral and acommunal, yet there seems to be, from my own lens, a desire in people for consensus on what moral life ought to look like, for everyone, even without the romance. Either way, I appreciated your piece, and the question.

Comments are closed.