Brecon, Wales. On 15 November 1772, a freeborn Martinican “mulatress” named Marianne delivered a healthy son, whom she called Jean-Pierre. Little else is known about her except that she was the widowed daughter of Elizabeth, who had once been enslaved. When Jean-Pierre was baptized in his local Catholic church, he wasn’t given his own father’s surname but that of Marianne’s late husband. He was illegitimate and, consequently, carried and passed down to his sons the family name of a man he never knew and to whom he wasn’t related. That name was Clavier. Jean-Pierre was my great, great, great, great grandfather.

Jean-Pierre’s surname did more than just provide a family association. It also signified that, like his mother, he wasn’t among the enslaved population but instead was a member of the gens de couleur libres: the free people of color of Martinique. Yet he almost certainly had relatives who were still in bondage on that small sugar-producing island. And like everyone else in the Caribbean, the enslavement of the vast majority of the island’s population shaped his entire life.

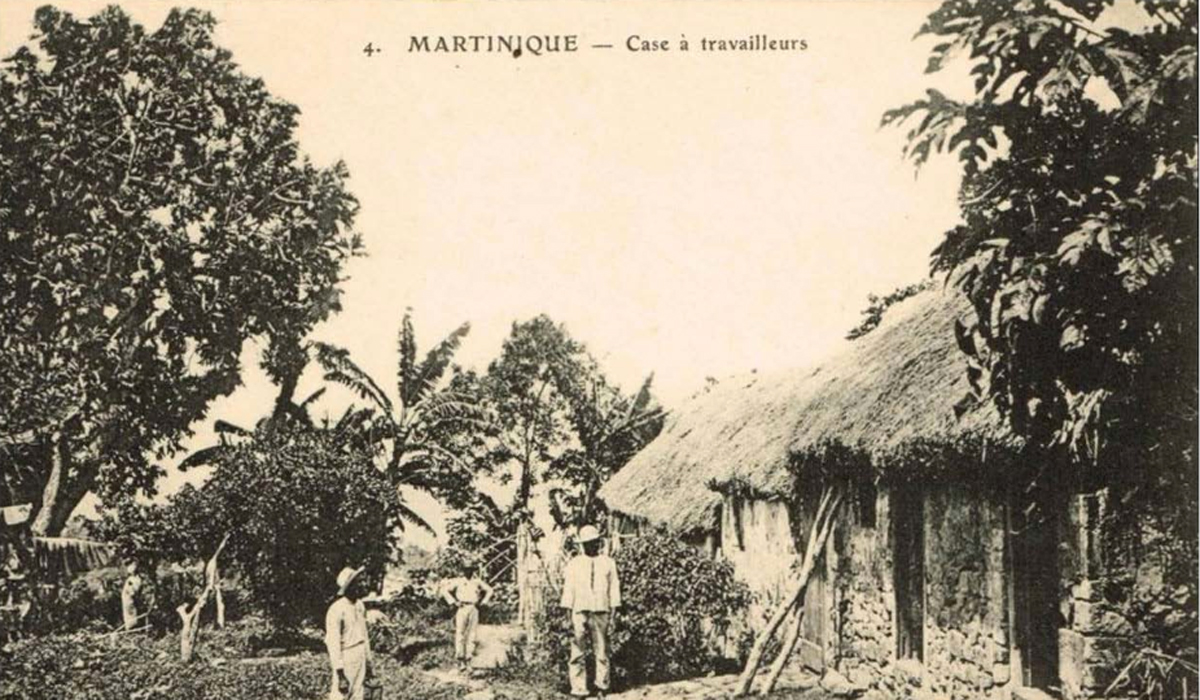

Despite his humble beginnings, Jean-Pierre became a man of means. Documents include him among the most prominent of the free blacks of Martinique. By the time he was a young man, he owned a farm that grew coffee and cacao, additional homes in Fort-Royal and across the channel in St Lucia, and a key post at his local port that granted him official status in wider Martinican society. Jean-Pierre later sent two sons to France for further education—his eldest son Antoine-Marie earned a doctorate in medicine and briefly taught on the faculty at the University of Paris before returning to the islands to be a doctor. Jean-Pierre wielded more actual power and influence than most of the ordinary whites on the island, and yet he also lacked basic rights like the right to vote or of assembly. All the same, to rise from slavery to one of the wealthiest families (black or white) in Martinique within two generations was an astonishing feat.

It was also a morally compromised one. Jean-Pierre’s marriage contract included among his assets four enslaved people, which increased to over thirty by 1800. When Britain abolished slavery, Jean-Pierre was compensated £41 18s 2d on 21 December 1835 for the emancipation of two slaves and another £477 15s 7d on 11 January 1836 for another nineteen (by then he was living in St Lucia). That’s roughly equivalent to £60,000 in today’s money. When his son Antoine-Marie returned from France, he married the daughter of a white plantation owner in St Lucia, though he doesn’t seem to have owned slaves himself. Oddest of all, his younger brother, Eugène Clavier, helped to abolish slavery in Martinique while profiting from a sugar refinery that depended on it. In that brutal world, the enslavement of others wasn’t just a white disease.

Jean-Pierre and Antoine-Marie are the earliest males of my Clavier line whom I’ve traced. Beyond them, Marianne, and Elizabeth lies the nameless anonymity of chattel slavery. Their story and my descent from them in the age of Black Lives Matter would be a remarkable story on its own. But there’s a particular irony contained in my familial descent from them:

You see, I am a white Southerner.

To be a white Southerner is to bear a relationship to race—historically, culturally, socially, and even religiously. One way or the other, you have to confront the issue and come to understand your place vis á vis racism past and present.

Recently, I perused a social media conversation about when participants realized they were white. I found this an unanswerable question because I’ve always known that I’m white. I knew that I was white because in the Southern culture of my childhood even those who thought of themselves as kindly-disposed towards African Americans still thought of them as them. There was us whites and them blacks and while we might get on well individually, we also accepted without question that a great cultural divide lay between us that was often traced through our towns by railroad tracks.

I knew too that I was white because I shared in the guilt of my Southern ancestors. The films I watched regularly hammered home the message that as a white Southerner I’m inescapably a bigot, either directly or by implication. Like many Southerners, I didn’t have a straight-forward way of dealing with this. That my Southern ancestors had fought on the wrong-side of the Civil War was undeniable. While my more ardent Southern friends tried to downplay slavery as a cause for the War of Northern Aggression, not even they defended the “peculiar institution” on which the Confederacy was built. So, unlike almost anyone else, we Southerners must figure out how to honor our ancestors while rejecting their moral outlook, which not only embraced slavery but even defended it at the cost of over 250,000 dead.

Like most white Southerners, I lived with these contradictions without really needing to resolve them. I felt ashamed that my ancestors defended slavery and later resisted racial equality, but I was also grateful I wasn’t a Yankee. Robert E. Lee was my boyhood hero; I even won a university scholarship for an essay extolling his virtues. I was glad the South lost; I was equally glad we gave the Yankees a good licking before we did.

Being a white Southerner taught me that racism isn’t easily resolved because it infects our loyalties, affections, and familial instincts. Our goods and evils are too entwined to be pried neatly apart. There is for us no offer of an unsullied cultural identity or a heritage we can blithely celebrate. The South is my home, though I’ve not lived there now for thirteen years. Instinctively, I think of Southerners as my people, my compatriots, though I share neither their Evangelicalism, politics, nor their love of grits and NASCAR. I also belong in some way to them all, no matter their race or their views on race. I may not defend my region right or wrong, but I feel obliged to love her folk right or wrong. Slavery, racism, Jim Crow laws, lynchings, and the whole system of racial inequality are inextricably part of my cultural heritage. Like the mark of Cain, that past continues to mark who we are, even those convinced they’re clean. The sins of our fathers are, indeed, visited upon their children’s children.

More than any of this, however, I’ve always known I was white because I knew also that my Clavier family’s whiteness is only a recent phenomenon. I didn’t then know about Jean-Pierre and only vaguely about Antoine-Marie. But an old photo of my black great-grandfather Louis, who emigrated to Britain after the War, adorned the top of an old bureau in our living room. I grew up knowing about him and his illustrious pedigree. The black Claviers were prominent doctors and lawyers, one knighted for his services to the British Crown and another awarded the Legion of Honor for his services to the French Republic. Louis’s father attended school with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle along with his close friend and cousin, Joseph Alexandre Lestrade, the inspiration for the Inspector Lestrade of the Sherlock Holmes stories. Frankly, they were far more interesting than my white Southern ancestors about whom I knew little.

So, not only do I have black ancestry, but I also grew up enormously proud of that heritage, dimly aware that the whiter we Claviers have become, so too the poorer. This left me with a rather complex attitude towards the question of race, to say the least. On the one hand, it inoculated me against intentional racism. How could I think of African Americans as anything other than my brothers and sisters when black blood runs in my own veins? In some places in the South, I would once have been classified as black under the notorious “one drop rule.” On the other hand, the color of my Clavier ancestors in the West Indies has never borne any relation to my day-to-day life; I’ve never looked anything but white, have never been considered anything other than white.

My mixed-race ancestry taught me from the start that race isn’t absolute. My white skin doesn’t mean I’m any less related to my black ancestors than to my white ones. And if that’s the case, I long ago supposed, color should play no role in distinguishing between people socially or culturally. Racism is a matter of attitude, a deliberate choice to treat our neighbors individually and systematically as strangers, even as enemies. It is to treat that which is superficial (race) as though it were everything. In this respect, racism is fundamentally a form of collective madness, replete with all the antagonistic irrationalism of psychosis.

That lesson was a valuable gift of my mixed-race background. At the same time, I foolishly imagined that my black heritage absolved me from the crimes that marked my Southern past and present. I readily admit that this was a delusion (at the very least ignoring the fact that I’m only half a Clavier), but it was one I happily embraced along with my dual British citizenship to escape sharing culpably in American racism. Without ever being conscious of it, I arrogated to myself all the privileges of being visibly white while also cleansing myself of any guilt through my black ancestry. You might say that I convinced myself that my black ancestry made me morally whiter than snow.

And then I discovered that Jean-Pierre owned slaves.

That realization came only recently after watching a documentary about those in Britain who were handsomely compensated for the emancipation of their enslaved people. I went to the online database featured in the program, typed in “Clavier,” and was immediately presented with two entries for Pierre Clavier: the Jean-Pierre mentioned earlier. I was stunned by what blinked back at me from my screen. I had always been grateful that none of my Southern ancestors owned slaves. Not once had it occurred to me that my black ancestors might have. What was I to make of the fact that the family stain of slavery marks my Afro-Caribbean ancestry but not (except by implication) my white Southern ancestry?

How was I to come to terms with the fact that I’m a white Southerner descended from enslaved Africans who subsequently became slave-owners?

I later found ways to begin answering that question in Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon’s exploration of the psychological impact of slavery and racism on Martinican society. He recalls a conversation with a young black woman enthralled by the opulence of the wealthy elite. She remarks that in Martinique a person is “white above a certain financial level.” Reflecting on this, Fanon comments: “It is in fact customary in Martinique to dream of a form of salvation that consists of magically turning white.”

Fanon’s statement struck me hard, and the force of its impact lay the realization that I embody his keen observation. No matter how prominent and wealthy the Claviers became, their position in society remained precarious as long as they were black. Jean-Pierre himself experienced this in 1822 when he was hauled before a kangaroo court, accused of collaborating with slave insurrectionists, and deported forever from Martinique; not all his wealth and status could protect him from being black in a society ruled by fearful whites. Whether this social precarity encouraged Clavier men to marry, generation after generation, either white or light-skinned women I’ll never know. But because they did, I’ve never experienced, nor ever will, what it’s like to be black. My line of Claviers found salvation from racism by “magically turning white.”

Moreover, like many free blacks in a deeply racist society, they sought salvation by adopting the dress, education, wealth, and even slaves of the white elite. A portrait of my great, great grandfather reveals a black man who was every inch a Victorian gentleman, complete with pince-nez glasses and a formidable moustache. Probably nothing in his life, except the color of his skin, identified him with the poorer blacks around him; he undoubtedly felt most at home with whites. Ironically, then, from a Martinican perspective, even my black ancestry is white.

I do not say this in an accusatory way. To think that a successful black family in the West Indies during the early 19th century had any other choice is to cross into fantasy. One may wish that they had rejected worldly fortune for noble principles, but it’s one thing to hope for saintliness and another thing to demand it. My family were as much creatures of their own time as we are of ours. We all share in the moral failings of our society, especially the successful among us. To a greater extent than most of us care to confess, the degree of our affluence marks also the degree to which we’ve compromised with an unjust world.

Whatever money and influence the Clavier clan amassed disappeared long before I was born. Some was buried when Mount Pelée erupted in 1902, a great deal vanished during the Depression, and what remained was didn’t survive by my grandfather, a man who earned the Military Cross during the Battle of France, was captured at Tobruk, and spent much of the rest of the war as a POW in Italy. Today he would probably be treated for PTSD. So, the glory of the Clavier line thus came to its conclusion in Wales, an ocean apart from the warm sunshine of the Caribbean but oddly only a short drive from where my own life has taken me. All my father inherited were half-remembered stories, family legends, and a surname that no one can ever pronounce.

My family story, however, offers a lesson in microcosm about systematic racism and the other injustices that underpin the social order. By all accounts, my ancestors were decent folk who dedicated themselves to the welfare of their communities. They were, in fact, a strikingly successful black family in a world strongly biased towards whites. Yet, they also shared in the material benefits of a society underpinned by institutionalized racism. In the society to which my ancestors belonged, you could not be wealthy and influential, no matter your color, unless you somehow participated in or condoned the slave system and accepted white supremacy. We take for granted the kind of racial solidarity and sympathy for the marginalized that seem to have been rarer in those days. That the free people of color, including my family, weren’t far removed from their own enslavement did not prevent them from owning slaves and even allying themselves with plantation owners to protect their own interests. Self-interest trumped everything else.

Today, the descendants of the Claviers in the United States, Canada, South America, the West Indies, and Great Britain run the gamut of racial complexions. We share an ancestry that contains triumph and shame and lives worthy of both praise and condemnation. There’s no separating them into the good and bad, the commendable and the corrupt. As with us all, sin and virtue were too intertwined to permit easy judgement. We, their descendants, are also the fruit of their morally complex lives, each of us working out in our own context how best to live virtuously just as they once did. In other words, we’re simply Claviers, branches of the same family tree, no matter our color. Whether I or my relatives will be any better than our ancestors is for God to decide.

Lest I end on a note of judgement, allow me to look to my surname for a sign of redemption. In hearing about my family story, a friend sent me a photo of a piano keyboard with the comment, “Claviers have always been symbols of the interdependence — interchangeability, indeed – of black and white.” Not even the most accomplished pianist can play without both the black and white piano keys. A keyboard contains no hierarchy of color, the misplaying of any one affects the sound of all. Each key is required to achieve beauty. But when played together well, how majestic is the sound.”

8 comments

Jim Clavier

For me, absolutely riveting article. I knew very little of this. Thank you for filling in the gaps.

Mark Clavier

Thnks, Jim!

Russell+Arben+Fox

I agree with Rob G. above; this is a great essay, skillfully opening up questions, and then questions about those questions, but never falling back into any kind of shoulder-shrugging mystery–all throughout, the goal of understanding and compassion remains. Thank you for sharing it, Mark–I hope to have the chance to read your history of your Afro-Caribbean ancestors someday!

Leroy See

Beautifully told story. All of us are a mosaic of biological origins with superimposed cultures and prejudices that muddy the water of understanding each other as being “just people.” In my case I am from genuine Oklahoma redneck stock of German origin in the 1700’s. In chasing down who I am I discovered that I probably have American Indian in my blood. In chasing that down I discovered that The Five Civilized Tribes relocated to points west of the Mississippi took their black, white, and Indian slaves with them. Intermarriage in all directions occurred but a hierarchy of tribal racial purity prevailed with a pure Indian on top. What blend of an admixture of Indian blood, if any, is in my veins is the question of the day because I am Caucasian in appearance. All of that mosaic matters not in my relationships with “just people.” Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King’s dictum that character is was really matters, and trumps all else, is where I find peace amid the racial rhetoric and political posturing of those who seek to divide people from people. Long gone is the day I would have cast the first stone.

Thank you once again for your thoughtful story of your mosaic family.

Brian

I can’t relate to any of this at all. The notion that you or anyone else, no matter your race, religion, geographic home, etc., bears any sort of culpability or shame or any other negative word you can think of based on anything to do with your distant forebears, or that you need “redemption” (!!!) from it, is the most bizarre and horrific and destructive concept I can think of, and it is totally insane that it is on the rise (!!!!!!) instead of completely disregarded as something totally incompatible with modern civilization.

Rob G

Berry’s The Hidden Wound may shed some light on that for you.

Rob G

This is precisely the sort of story that needs to be heard, as it throws a spanner into the works of the over-simplistic racial ideas that currently dominate both sides of this issue. For a thoughtful fictional treatment of a somewhat similar story see Glenn Arbery’s recent novels Bearings and Distances and Boundaries of Eden.

I remember reading a quote somewhere that said that one of the great tragedies of the Civil War era was that the North came to believe that all slaveholders were like Simon Legree and the South that all abolitionists were like John Brown. I think that a modern version of this error still runs rampant in contemporary discussions of the topic, except that it no longer necessarily contains the old geographic element.

Mark Clavier

Thanks Rob. I agree entirely. I often complain that in books and films Southern racists are so often portrayed has entirely villainous in an almost cartoonish way. I think it would be much more interested to portray them sympathetically, to highlight the moral ambiguities of their lives, and thus also highlight the truly noxious ways that racism (or any other vice) can become entwined with virtue and decency.

Comments are closed.