Between the time in which this interview took place and the time in which I sat down to edit it for publication, Facebook rebranded itself as Meta and the public outcry at the company’s shady censorship practices turned into public meme-ification at the brave new augmented reality of Zuckerberg’s Metaverse. Creative destruction moves fast, and attention spans are short.

Yet while last month’s news cycle is already becoming a distant haze for some, we wanted to think a bit more historically about the significance of the leaked Facebook papers and the current policy ambiguity about how (or if!) to best curb and guide freedom of speech in ways that serve the commons.

In an important essay in The New Atlantis, author Nicholas Carr (The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to our Brains, and The Glass Cage: How are Computers are Changing Us) makes a very compelling case that this current confusion about how to regulate social media is partially tied to our collective amnesia. We are people with limited historical attention. In his essay, Carr goes back over 150 years to look at the emergence of radio, telegraph, telephone, cable, and digital technologies that predicated the growing need for regulatory bodies like the FCC.

To curb the freedom of speech has always been a challenge, particularly as new technologies for speech blurred lines of public and private. But Carr’s hope is that “the way the country met the challenge a hundred years ago, haltingly but effectively, holds important lessons for us today.” Go and read Carr’s takeaway lessons in his essay, but in this context, we thought it might be intriguing if we looked at other fraught moments in history where questions about communication and censorship, politics and propaganda, freedom and government intervention came to a head. What might we learn from such moments?

We were delighted to think through this with Paul Kemeny of Grove City College, Richard Gamble of Hillsdale College, and Ben Faber of Redeemer University. In their own way, each helps to illuminate our present moment with light from the past.

Doug Sikkema: As we look at the current situation around regulating a new digital, mass communication technology, we are tempted—at least I am—to think: “We have never been here before.” There is perhaps always a certain truth to that. But for those of us who spend a lot of time digging around in the past, we also realize that other moments have enough similarity to still be instructive. I’m curious to hear from each of you about a historical moment that might surprise us in how it dealt with the fraught issues of free speech, emergent technologies, and the sticky business of censorship.

Paul Kemeny: In the late nineteenth century, liberal Protestant elites, typically considered progressive, urbane, and tolerant, established an anti-vice organization, the New England Watch and Ward Society, to curb the growing rise of allegedly obscene literature. These self-appointed custodians of Victorian culture enjoyed widespread support from many of New England’s most renowned ministers, such as Phillips Brooks of Trinity Church, Copley Square, distinguished college presidents, including Harvard’s Charles W. Eliot, and wealthy philanthropists, such as Godfrey Lowell Cabot.

Obscene literature was prevalent, and its popularity grew dramatically over the course of the nineteenth century. Several developments fueled its growth. Advances in printing technology—the invention of machine-made paper, mechanical typesetting, stereotype plates, and high-speed, steam-powered cylindrical presses—made the publication of obscene literature easier and more profitable. At the same time, an expanding postal system and a growing railroad network made it easier to distribute licentious works. When federal authorities attempted to curtail the importation of obscene material from Europe, they unwittingly helped launch an indigenous erotica publishing industry.

The Watch and Ward Society used four tactics to “safeguard” public morality from obscene material. Building upon the 1873 Comstock Act, which had strengthened federal laws against using the postal system to distribute obscene material, they introduced additional legislation to criminalize the sale and distribution of such material in each New England state. Second, the organization pressured the police, both privately and publicly, to enforce these laws. Third, the society’s agents functioned as an extra-legal police force and gathered evidence against obscenity dealers and then took it to the police. Finally, they directly pressured bookstore owners and publishers to conform to the obscenity laws.

Richard Gamble: When I began researching my PhD dissertation in the late 1980s, I hit on the problem of the activism of the social gospel clergy in America during the First World War. Purportedly committed pacifists, the leaders of the movement in large numbers supported the war, not merely for the sake of an Allied victory over the Central Powers, but to seize on what they called a “plastic” moment in America and the world to remake the economy, politics, the church, and international relations.

Through agencies such as the Federal Council of Churches, they produced sermons, Sunday-school lessons, hymns, and bad poetry to mobilize the nation for an idealist crusade. Today, I refer to this phenomenon as “self-mobilization”—a reaction to war not confined to the liberal clergy in America or to WWI. My research and writing have moved away from the First World War, but I have continued to write about American civil religion, especially in war and other times of crisis.

All sorts of people “self-mobilize” in times of crisis. The national government hasn’t always had to resort to force to get people on board with the war, its aims, and its costs. Of course, there was conscription; there was nationalization of the railroads; there was intervention in banking, industry, and consumption; and there was censorship.

But right along with these efforts were all sorts of pastors, politicians, publishers, journalists, and others voluntarily preaching the “official” Wilsonian version of the war (not the only version available or best suited to secure victory and a realist peace). No government edict forced churches to display American flags in their sanctuaries. No government agency forced preachers to find the Great War in their Bibles and sell it to their parishioners. No government agency forced congregations to sing the “Star-Spangled Banner,” “America,” or the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” in public worship.

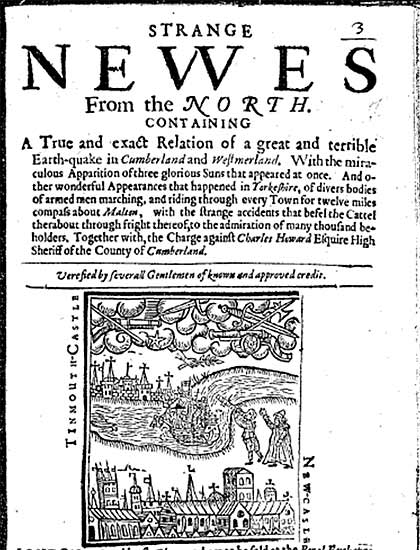

Ben Faber: The focus of my doctoral research was the role satire played in the public discourse of politics and religion during the English Civil Wars (1640-1651). I was especially intrigued by how shaming rituals in 17th-century popular culture were translated into the satirical pamphlets that flooded the London book trade during the most crucial stages of the ideological battles between Royalists and Parliamentarians. In the early stages of the revolution, the traditional mechanism for the licensing of printed works was disbanded, which allowed virtually anyone to have their views—conservative or subversive—appear in print.

Printers’ apprentices, apparently disgruntled by the monopoly of the Stationers’ Company, were setting up clandestine presses to print pamphlets, quickly and cheaply. These were often printed on a single sheet that was folded twice into an 8-page leaflet. This period also saw the rise of competing newsbooks, called “corantoes” or “Mercuries,” which reported battles between the King’s army and that of Parliament, as well as foreign news. Sometimes referred to as “cheap print,” many of these pamphlets, broadsheets, and newsbooks were sold on the streets of London.

And the satire on all sides was snarly and snappy, bitter and biting, often blending classical literary forms with popular cultural shaming practices. In other words: easy access to opinions of all kinds, in a medium that could respond quickly to events, with mis- and dis-information coming from various and frequently anonymous sources, marked by personal attacks and allegations, at a time of serious social and political upheaval.

When Parliament re-introduced pre-publication licensing in 1643, effectively restoring a system of government control over the printing press, John Milton responded with Areopagitica, a work that is regarded as one of the foundations of modern liberal democracy in general and of the First Amendment in particular. At the heart of John Milton’s commitment to what he called ecclesiastical, domestic or personal, and civil liberty is his vision for a godly nation that is left free to choose rationally between truth and error, goodness and evil: “Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience above all liberties.”

Doug Sikkema: From these “historical friends” in the Victorian Era, early 20th century America, or even Restoration England, what we might learn about the boundaries and limitations that are necessary for free speech to be both fruitful and conducive to a robust “life together”?

Paul Kemeny: The history of the Watch and Ward Society’s censorship activities demonstrates that there is no “golden age” in nineteenth-century America where people shared a healthy vision or consensus over the limits of free speech that would empower them to pursue a robust life together. Instead, the history of the society’s efforts to determine the boundaries for what literature was morally acceptable for public consumption was always contested by those who did not share the Protestant moral reformers’ underlying principles.

One way of framing the debate over the censorship activities of the Watch and Ward Society that may shed some light upon contemporary discussions about free speech is to see it as part of an ongoing contest between the Whig-Republican and Jeffersonian traditions in American history. The Protestant moral reformers, heirs of the Whig-Republican tradition, stressed self-discipline, rational order, and social responsibility. Consequently, they maintained that the state should protect people from the corrupting influence of allegedly obscene literature. Neither the free market nor personal liberty, they insisted, should determine what was moral or immoral.

These Protestant Republicans saw themselves as their brothers’ moral keepers and consequently attempted to regulate public morality through their anti-vice organization as well as state and federal laws. In contrast, their detractors, such as the poet Walt Whitman, the free love activist Ezra Heywood, and the journalist H. L. Mencken, embraced the more libertarian strain of the Jeffersonian tradition which sought to completely remove religion from public life. Consequently, they stressed the preeminence of personal liberty over Protestant morality and social order. What people read, they argued, should be left to personal discretion, not the state and especially not a self-appointed voluntary organization of censors.

Richard Gamble: Censorship during WWI (and before and since) has to be placed in this larger context of speech, free or otherwise, in a mobilized nation-state. Do we have a word for this tendency? It’s not censorship, and its effects might be more consequential than censorship. Should we just call it conformity? It involves self-censorship and self-mobilization in a cause, the force of public opinion and not the force of law and police.

Before returning to this wider problem, I have to say that government censorship and coercion were very active during WWI, and I don’t want to downplay their significance. The story of this censorship and coercion still has the power to shock us. I meet people all the time who have no idea how far the central government went from 1917-1919 (at least) to control speech and action. Since we didn’t experience the same degree of censorship during WWII or in subsequent wars, we tend to think that nothing so “un-American” ever happened here. But it did. The government (national and state) used two strategies: 1) flood the nation with the official view, and 2) silence and even imprison critics of the war and Wilson administration. George Creel and his Committee on Public Information (CPI) falls into the first category. Every form of media was employed: press releases, scripted speeches, posters, songs, movies, and phonograph records. The “Creel Committee,” as it was popularly known, produced an endless stream of propaganda (in the older and newer sense of the word). “Four-Minute Men” promoted the sale of Liberty Bonds and conservation in movie theaters between reels. The CPI made some speech as loud as possible. When Creel wrote about his war service, he didn’t hold back. He called his history How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe (1920). I think the title and subtitle go far in demonstrating why publicity is as serious an issue as censorship. Its goal is group-think and group-act.

The second wartime strategy undertook direct prohibition of and interference with free speech. U.S. Postmaster Albert S. Burleson denied the mails to newspapers and magazines deemed subversive. This power was used not only against radical socialist publications, such as the Masses, but against newspapers that criticized Wilson, criticized the British or French, or opposed the draft. There were other organizations, such as the Council of National Defense, and similar bodies cooperating with it in nearly every state, that reported on rallies opposing the draft, neighbors who refused to contribute to the Red Cross, and so on. The Agriculture Department sent agents from house to house to ask housewives if they were conserving food and wrote the response on index cards. Enemy aliens were sent to the federal prison in Atlanta for the duration of the war. The prison housed at least one South Carolina editor and enough German musicians to form an orchestra (complete with conductor).

Ben Faber: I earlier summarized the pamphlet wars of the 1640s in terms that sound familiar to us today. At the same time, we should not exaggerate the similarities in our widely differing contexts. The debate about free speech today involves not simply a Parliamentary committee for the regulation of the printing press in England; the global, corporate machines that control social media cannot be regulated as easily. Nevertheless, John Milton’s plea for unlicensed printing sets out principles that bear paying attention to.

First, Milton notes that liberty is not the same as license, that is, unrestrained or unchecked behaviour that indulges the self at the expense of another. As John Locke later argues, liberty is a freedom that always functions within law. The parameters within which we exercise free speech today, as many acknowledge, do not permit such things as libel and hate speech. The parameters that circumscribe freedom of speech should be demonstrably grounded in natural law and in universal rights, not in political ideologies or national interests.

Second, Milton argues that, while the “liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience” is individual and personal, the context is corporate and public. In Areopagitica, Milton pictures England as a nation of rational, godly individuals. In the 17th century, reason was both the faculty that every human being possesses and the activity of logical processes that one exercises in discourse with others. For Milton, a godly nation was one that practiced the Christian religion free from custom and error. It is no accident that Milton also wrote a treatise on education in 1644: essentially, Of Education describes the formation of the virtuous and noble person “to perform justly, skillfully, and magnanimously all the offices both private and public of peace and war.” In order for freedom of the press to function positively, Milton implies, you need a properly educated reader. A commitment to free speech today should be accompanied with a commitment to public education.

Third, Milton holds that difference, error, and even heresy are necessary for truth to flourish. How can you know right from wrong, when you never encounter the wrong? How can you prepare a reasoned defense for your position when you cannot hear the contrary argument? Just as law, reason, and virtue are prerequisite for liberty, so toleration of differences is a necessary precondition for the flourishing of free speech.

Doug Sikkema: What are some of the ways in which speech ought (not) to be constrained today? Who or what should exercise that authority? How does “free speech” change with scale from an institution to a community to a nation state to a globalized, pluralistic world?

Paul Kemeny: First, let me say that I do not think that I am qualified to answer all of these questions.

The history of the Watch and Ward Society casts some light upon the debate of free speech in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that may inform our current conversation. During this period, Protestants largely dominated the key culture-gatekeeping institutions of American society and presumed to speak for most Americans when they censored obscene literature. Today, Protestants do not enjoy this kind of cultural influence.

Various boundaries define free speech today, and those norms are being contested as they were in the past. Today, however, American Christians live in a much more pluralistic culture. Christians should participate in discussions about what norms should limit free speech and where and how it should be restricted in the different venues in which it is debated. But Christians should do so in a tone that is consonant with basic Christian beliefs. Micah 6:8 is helpful on this point. According to the prophet, believers are to act justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with the Lord. Therefore, the language Christians use should embody these values. Christians should avoid histrionics and inflammatory rhetoric and resist demeaning caricatures that misrepresent those with whom they have serious disagreements. Although it may seem naïve to some, engaging in the Nietzschean politics of ressentiment, which is grounded in a narrative of injury and as a sense of entitlement, betrays basic Christian principles and will likely fail dramatically in our current political climate. Unlike the Protestant moral reformers of the early twentieth century who presumed that their viewed shared widespread public support, Christians today need to learn to speak and to act for the common good more effectively.

Richard Gamble: What I am groping toward here is the point that there is more than one way to make something “unsayable.” Government, with the power of force behind it, can outlaw certain kinds of speech, or ordinary citizens—well-meaning and nefarious—can use the pressure to conform to control how others act and what they say and don’t say/can’t say. Maybe we need a history of the “unsayable” in America.

One chapter of that book would have to be about Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. While we rely far too much on this one book for our understanding of 1830s America, Tocqueville’s comments about speech are right on target. The public in a democracy would feel compelled to conform, and it wouldn’t take a police-state to do it. We would do it to ourselves:

So the public among democratic peoples has a singular power the idea of which aristocratic nations would not even be able to imagine. It does not persuade, it imposes its beliefs and makes them penetrate souls by a kind of immense pressure of the mind of all on the intelligence of each. In the United States, the majority takes charge of providing individuals with a host of ready-made opinions, and thus relieves them of the obligation to form for themselves opinions that are their own. A great number of theories in matters of philosophy, morality and politics are adopted in this way by each person without examination on faith in the public; and, if you look very closely, you will see that religion itself reigns there much less as revealed doctrine than as common opinion. [Emphasis added].

If, today, we no longer conform our ideas to the “ready-made opinions” for the sake of our “faith in the public,” we do conform them to our little “publics” and what our little publics hate and love. This is certainly my experience with Facebook. I miss the days when people posted pictures of their boring breakfast.

Ben Faber: This is a tough question. Freedom of speech is not a free market commodity, nor should it be treated in a laissez-faire manner. However, because it is a right exercised by the individual, it is also not primarily or exclusively the remit of the state to regulate or control. Who then sets the parameters within which this freedom is best exercised, and who polices the practice and who punishes its violation?

It would be appropriate for an institution, whether in business or education or religion, to require of its voluntary members agreement with constraints on their speech as it pertains to the mission of the institution. If someone publicly bad-mouths their boss or openly undermines the mission of the institution by their speech, they can expect to be reprimanded. At the levels of the community and the nation state, the health of the body is maintained by the free, open, and transparent engagement with dissent. Before opinion becomes knowledge, and before knowledge becomes wisdom, a community or a nation needs to attend to diverse articulations of experience.

Within an institution, community, nation, and even globally, the expression of worldview diversity is an antidote to stagnation, intolerance, and bigotry. Since the end of the Second World War, organizations such as the United Nations, the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, and the International Atomic Energy Agency have done much to stabilize the volatility of nationalist tendencies.

However, the dominant influence of Western culture through language, commerce, entertainment, and social media is unravelling the global tapestry and is subtly encouraging conformity to sameness. International sanctions can be levied against states that contravene the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Freedom of speech and belief, however, is an aspiration in the Preamble to the Declaration, not an article in its own right. The policing and punishing of the freedom “to know, to utter, and to argue freely” resides with the nation state, whose responsibility it is to ensure the context in which this freedom can be exercised responsibly. Because I have not adequately answered the question, let me recommend a piece by Nicholas McDowell on the relevance of Milton’s Areopagitica published earlier this year.

Doug Sikkema: What historical circumstances create particularly sharp debates about free speech? Are there technological and cultural conditions we need to be attuned to?

Paul Kemeny: Context is crucial for understanding why the debate over censorship and free speech were so heated during the 1920s and why critics successfully subverted the Watch and Ward Society’s role as the region’s literary censors.

Following World War I, there was a widespread rebellion against Victorian mores, especially among young Americans who had witnessed first-hand the horrors of war. Grand changes were also taking place in American literature that displayed this rebellion against Victorianism. The Genteel Tradition of Victorian literature had not only fallen out of favor, but naturalism in fiction as evidenced, for instance, in Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (1925), grew in popularity. To aging Protestant moralists and New Humanists such as Stuart Sherman, naturalism was literary realism gone awry, but to cultural modernists the genre captured the brutalities of life. To cultural modernists, literature, like other expressions of art, should be judged only by aesthetic criteria untethered to Protestant moral standards.

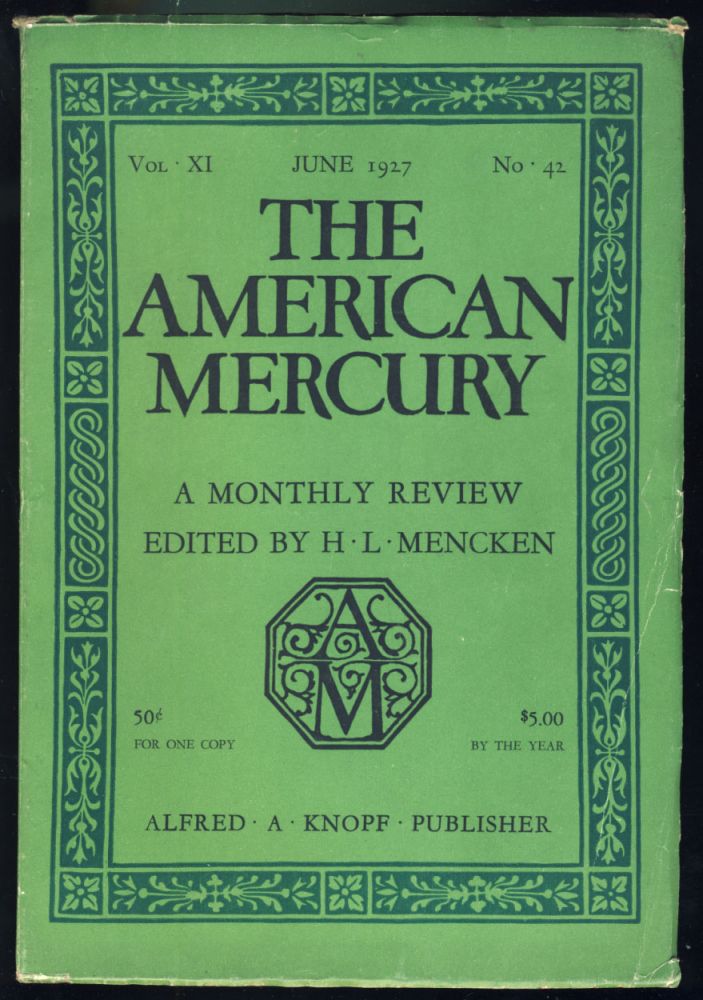

Another important cultural condition was the emergence of avant-garde publishers, such as Albert Boni and Horace Liveright, who were eager to publish modernist writers. Likewise, avant-garde publishers financed new popular magazines, such as H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury. These books and magazines gave the critics of traditional Protestant values a new vehicle through which to broadcast their views on free speech and literature.

The backlash generated by the Wilson administration suppression of free speech rights during the First World War and after it also played a critical role in raising concerns about intellectual freedom. The suppression of free speech gave rise to the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920 which marshalled significant legal and financial resources to protect free rights.

While Protestant moral reformers in previous decades had critics, in the 1920s they faced even greater challenges. An ideological antagonism toward Protestantism, economic self-interest, and a commitment to civil liberties brought together a coalition of civil libertarians, modernist authors, and avant-garde publishers. These critics ridiculed the Protestant reformers’ privileged backgrounds, social idealism, and religious commitments. This coalition successfully mobilized public sentiment against the Protestant traditionalists and their censorship activities and won the day decisively in both the courtroom and the arena of public opinion for two critical reasons. In novels, such as Elmer Gantry, and publications, most notably the American Mercury, they used ridicule, or ressentiment, to discredit and silence the moral reformers. Even if works by Sinclair Lewis and other modernists unnerved many Protestant readers, they successfully demonstrated in courtrooms and then state legislatures that literary naturalism was not genuinely immoral by the standards of the day.

D. H. Lawrence’s view of pornography offers insight on these two points. Lawrence defined pornography as “the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it,” and he admitted that “even I would censor genuine pornography, rigorously.” In his landmark 1933 decision, Judge John Woolsey drew upon Lawrence’s definition when he determined that James Joyce’s Ulysses, although “disgusting” in many places, did not contain “anything that I consider to be dirt for dirt’s sake.” Despite “its unusual frankness,” he concluded that the novel was not “pornographic.” Woolsey’s decision, coupled with revisions to numerous state laws defining obscenity, successfully reformulated the parameters of morally acceptable literature and largely ended the Protestant moral reformers efforts to regulate anything but the most widely recognized forms of pornography.

Richard Gamble: What we have going on here are three interwoven problems at once: Censorship, conformity, and corruption of language. I can only handle this third element briefly.

The worry about corruption of language is as old as Thucydides and Plato. Here’s Thucydides writing about what happens to language in times of civil strife:

To fit in with the change of events, words, too, had to change their usual meanings. What used to be described as a thoughtless act of aggression was now regarded as the courage one would expect to find in a party member; to think of the future and wait was merely another way of saying one was a coward; any idea of moderation was just an attempt to disguise one’s unmanly character; ability to understand a question from all sides meant that one was totally unfitted for action. Fanatical enthusiasm was the mark of a real man, and to plot against an enemy behind his back was perfectly legitimate self-defense. Anyone who held violent opinions could always be trusted, and anyone who objected to them became a suspect. [Emphasis added].

Sound familiar?

And here is Socrates speaking in the Republic about the corruption of the soul when virtues no longer guard at the gates. The “false spirits” make “an alliance with desires” in the city of the soul, and one of the casualties is the meaning of words:

[They] banish modesty, which they call folly, and send temperance over the border. When the house has been swept and garnished, they dress up the exiled vices, and, crowning them with garlands, bring them back under new names. Insolence they call good breeding, anarchy freedom, waste magnificence, impudence courage.

Sound familiar?

I would reprimand my students if they dumped block quotations like this into a paper with so little commentary and analysis, but my thoughts about all of this are tentative. In fact, I had never thought about the close relationship between censorship, conformity, and corruption before this interview. All three of these tendencies are being played out simultaneously on Facebook today. And we have to admit that while we might be victims in some ways, we are also active participants in what is happening to language. We have to look to ourselves as well as government and corporate America.

Ben Faber: At times of cultural change, the old answers may no longer fit the new questions. When an old paradigm needs to be challenged, freedom of speech is both necessary and discomfiting. Change disrupts our set patterns and practices, and we may resist attending to new voices and to radical ideas. But it is precisely when language ossifies into cliché that we need novel articulations and fresh expression, as George Orwell argued in “Politics and the English Language” (1946).

At times of cultural crisis, too, freedom of speech allows a society to think together of the origins, consequences, and solutions of the crisis. Freedom of speech is the public mechanism by which the hive mind of society thinks aloud and collectively processes the thoughts and feelings generated by the crisis. Change and crisis are threats to the social fabric when free speech is denied.

Currently, COVID and global warming are two critical moments of change and crisis. Milton’s call for “the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely,” within the parameters of law, reason, and respect for difference, is for such a time as this. But we must understand that education is the corollary to freedom of speech. The virtuous and noble education that Milton projected was based on classical and Christian humanist models, which also happen to be the models upon which English and American liberal democratic institutions were built. (Thomas Ricks, First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned From the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country (NY Harper, 2020) is good on this subject.)

We can translate these models of education in our pluralistic context as learning the values of historical perspective, critical thinking, logical argument, civil disagreement, and the virtues of empathy, charity, and humility. While technology changes at increasingly rapid rates, the fundamental means of discerning truth from error, right from wrong, and good from evil, remain constant. My final word, then, is a plea for the renovation of public and private education in order to equip everyone for the responsibility of speaking and listening “justly, skillfully, and magnanimously,” as Milton puts it in Of Education.

Paul Kemeny is Dean and professor of Religion and Humanities at Grove City College and author of The New England Watch and Ward Society, New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Ben Faber is an Associate Professor of English at Redeemer University (Ontario, Canada), where he teaches courses on Shakespeare, Milton, Romanticism, and Literary Theory.

Richard Gamble holds the Anna Margaret Ross Alexander Chair in History and Politics at Hillsdale College and author most recently of A Fiery Gospel: The Battle Hymn of the Republic and the Road to Righteous War, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019