Reeds Spring, MO. I was a teenage Anglophile. I have one overwhelming memory of my last two years of high school: a musty college library basement, where I meandered among the stacks with my “community member” library card and discovered works by John Donne, George Herbert, G. M. Hopkins, G. K. Chesterton, J.R.R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis, works that propelled me into a college degree focused on British literature and ones that still shape my reading life today.

In writers like these I discovered many things but especially a sense of the past. To my teenage self, reading The Lord of the Rings or Donne’s “Holy Sonnets” opened up historical and cultural vistas that my homeplace did not provide. Southeast Nebraska, where I lived, was a place that showed few traces of history: it was a landscape of ranch houses, cornfields, and highways. It was only in my reading that I could gain a sense of a culture that stretched back before the twentieth century.

At the same time, I was a fervent Nebraska partisan. I loved my home state despite—or perhaps because of—its humility, the quality that leads to the state’s current, tongue-in-cheek tourism slogan: “Honestly, it’s not for everyone.” For all that my reading was dominated by British literature, I never pined for England. I was content, in essence, where I was, even as I longed for a visible trace of history in the landscape around me. Although I had not yet discovered W.H. Auden at that time, I would have identified with his lament from the poem “In Transit,” composed in an airport:

Somewhere are places where we have really been, dear spaces Of our deeds and faces, scenes we remember As unchanging because there we changed, where shops have names, Dogs bark in the dark at a stranger’s footfall And crops grow ripe and cattle fatten under the kind Protection of a godling or godessling Whose affection has been assigned them, to heed their needs and Plead in heaven the special case of their place.

Like Auden, I wanted to live in a place with a name and a soul; I suspected that my home was not such a place, even as I longed for it to be so. I suspect many readers of Front Porch Republic can identify with these experiences: longing for a deeper history and a richer culture than one’s place offers; loving one’s place despite its thin and diminished culture and ecology. Trying to hold these impulses together can lead one into a posture that is something like absurdity—swooning over the dreaming spires of Oxford from a house abutting a soybean field, while nonetheless scheming with all one’s might to remain in that field. Localists, urbanists, and other dreamers are made of such pressures.

Living vicariously through the reading and art of an older culture is one way to endure this tension, but there is a better path. One might instead find ways to plunge deeply into the history of one’s own place, whether that history is apparent in the living landscape or not. If we in the Midwest lack ancient buildings, the land itself has been here since antiquity—and so have the First Peoples who called it home. If we seek a sense of history in our disrupted places, then, we might start by learning something of their stories.

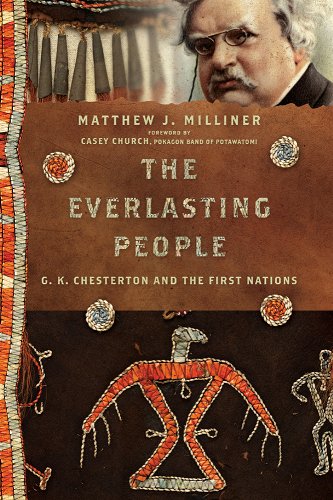

In The Everlasting People: G.K. Chesteron and the First Nations, Matthew Milliner offers a unique look at the history and visual culture of America’s first inhabitants. Reflecting on the art history of Indigenous North American peoples in light of Chesterton’s Christian passion for justice, contentment, and local culture, Milliner strives to help us attain “contentment at our own hearthstones, but without forgetting those whose hearthstones were taken from them.” In so doing, he provides rich imaginative and historical resources to grow in love for and knowledge of our home—particularly for those of us descended from settlers to North America.

The book is undoubtedly timely given recent public discourse about race in the United States as well as the Dakota Access Pipeline protest. Yet one strength of this book is that it is not beholden to the terms of that increasingly toxic conversation. Milliner states his concerns with this discourse sharply: “There are at least two errors about racism currently circulating in North American culture. One is that it has been permanently defeated, and the other is that it is omnipotent.” On the one hand, The Everlasting People unquestionably affirms the systemic nature of American racism and its ongoing effects. On the other, in contrast with many current antiracist thinkers, Milliner’s approach avoids rigid binaries or simplistic narratives premised upon racial essentialism.

Much of the current discourse on race focuses legalistically on sorting out historical winners and losers and on determining whether and how racism continues to privilege whites and harm people of color. In contrast to this zero-sum approach, Milliner’s work proposes that the systemic and continuing effects of racist oppression harm everyone, because while they continue to materially disadvantage Indigenous peoples, they also alienate and separate descendants of settlers from the place where we live. “Until the crimes are acknowledged,” he asserts, riffing on Chesterton’s The Crimes of England, “the magic stays concealed.” Accordingly, The Everlasting People falls in a tradition of thought which sees American racism as a spiritual and cultural problem as much as an economic and legal one. It takes its place alongside the work of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, Wendell Berry’s The Hidden Wound, and James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. Like those works, which see anti-Black racism as a spiritual disease afflicting especially the South, Milliner’s positions the mistreatment of Native Americans as an open wound in the culture of the Midwest. Acknowledging that disorder is the first step toward health: “I have discovered that my wife and I are just as much guests on Turtle Island, a widespread Indigenous name for this continent, as we are respectively ‘Canadian’ or ‘American.’ Acknowledging this hospitality, which comes with considerable humiliation, is a first step toward calling this land home.” Only such acknowledgement can help us forge a “penitent Midwestern regionalism” that will foster love of our home not for what we would like it to be, but for what it truly is.

A further concern might be raised about the book relating to what Milliner calls the “thorny question” of appropriation—is it not another form of plunder for Milliner, a white man, to draw so heavily upon Indigenous resources? He is careful to clarify: to understand Native beliefs themselves, “I refer readers to Native persons themselves.” Milliner himself only borrows Native symbolism in order to “drive home the realities of settlement and the presence of Christ among the First Nations,” not with any intent to speak for Native peoples. Though this approach still risks an accusation of appropriation, Milliner suggests that such an approach is preferable to “the considerable risk taken by most North Americans by default: ignoring these symbols altogether.” Rather than profiting off Native motifs, then, the book aims to create a conversation between Indigenous art history and the Anglo-European culture of Milliner’s ancestry. In so doing, there is no attempt at gaining further profit from Native resources, but rather an attempt at fostering intercultural conversation and understanding. Milliner’s use of Chesterton here is a way of “examining the resources of one’s own ancestry” rather than “siphoning someone else’s” for some sense of cultural authenticity. Accordingly, it is fair to say that this is a book written especially for we teenage Anglophiles whose settler heritage has left us ignorant of the ancient culture of the land we now call home. It is a work of intercultural dialogue, rather than an attempt at seizing another’s culture for one’s own.

In that spirit, Milliner offers three essays that put the works of Chesterton into conversation with Indigenous art and symbolism. I will summarize each briefly to give a sense of his project, though each also has many rich images and reflections which I cannot do justice. I will give special attention to his first chapter, “The Sign of Jonah,” which examines the varying treatment of Christian converts in North America and is particularly indicative of his approach. Whereas Milliner and his ancestors found Christianity a path to social mobility, for Native Americans who embraced Christianity their new faith “registered no change in their treatment at all,” leading instead, all too often, to marginalization or even martyrdom at the hands of their fellow believers. Milliner thus concludes that “there are more spirits at work on this continent than the Holy Spirit.” He finds these spirits documented, in particular, in rock paintings.

He relates Chesterton’s reflections on cave paintings in The Everlasting Man to North American images of two supernatural creatures, the Mishipeshu and the Thunderbird. The Mishipeshu—also variously titled the Underwater Panther, the Great Lynx, Piasa, or the Beneath World Spirit—is understood in a variety of ways, including as a dark creature associated with harm, death, malignancy, and destruction. Milliner applies one of Chesterton’s insights from The Everlasting Man: “Human Christianity in its recurrent weakness was sometimes too much wedded to the powers of the world.” Such was the violent settler Christianity that oppressed Native Christians; Milliner comments, “for the original inhabitants of this land, the nightmare was us.” Even though many Native American tribes and individuals embraced the Christian Gospel that made them fellow-believers with European settlers, these Christians were nonetheless repeatedly driven off their lands, dispossessed, and persecuted. Milliner evokes the Mishipeshu to visualize the dark powers of greed and domination that took up residence where there should have been Christian charity and solidarity.

On the other hand, in the Native symbol of the Thunderbird, Milliner finds “evidence not just of the Christianizing of the Indigenous but of the indigenizing of Christianity.” Often found in contrast with the Mishipeshu, the Thunderbird is another common Native symbol with many meanings, but it is often found among Native Christians serving as an image of Christ: Milliner documents Native artworks (by Norval Morriseau, Ovide Bighetty, and others) and churches (the Indigenous Christian Fellowship of Regina, the Immaculate Conception Church on Manitoulin Island, and the Saint Kateri Center of Chicago) where this conjunction takes place. Native Christianity, Milliner notes, is often overlooked—either seen as representing social oppression by missionaries or capitulation by Natives. Yet “Native Christianity is not a mark of inauthenticity, as it is often perceived, but a sign of revitalization in the face of overwhelming pressure, a revitalization in full flight today.” The adoption of the Thunderbird as a sign of Christ represents the enculturation and translation of the Christian Gospel by Indigenous peoples themselves, a process echoed in every culture that wholeheartedly lays hold of Christian faith.

As such, the Thunderbird is a sign of creative resistance to oppression and one that is essential for Christians descended from settlers to recognize: “Perhaps only Indigenous North American Christianity can address the pervasive imbalance of Christian culture on the American continent.” Just as Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man documents the mythic reception of the story of Christ by early Europeans, so Milliner observes a parallel process going on among the Indigenous peoples of North America, one offering a parallel sign of hope and testimony to God’s love for all nations and peoples. All told, this first chapter gives a taste of Milliner’s approach throughout the book—both lamenting the legacy of American racism and seeking hope for renewal, all filtered through a learned and careful attention to Native symbol, artistry, and image.

In his second chapter, “The Cost of Chicago,” Milliner reflects upon contentment and imperialism by drawing upon the Native history of his home in Chicago and Chesterton’s mock-revolutionary novel The Napoleon of Notting Hill. I could expand upon this chapter at length as well, with its reinterpretation of the Chicago flag, prehistoric history of the Midwest, and account of Catholic ministry among Indigenous people in twentieth century Chicago, all historic details that have much to teach us about the broader culture of North America. Perhaps the most relevant portion of the chapter, though, is Milliner’s grieved commentary upon public monuments, which illuminates our culture’s broader debate about memorialization of wicked or bigoted past leaders.

He first provides an account of how the many tribes that once inhabited the Chicago region—Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Sauk, Kickapoo, Miami, Shawnee, Delaware—were defrauded of their land and violently removed from it. In particular the Potawatomi, the largest group in the area, were eventually removed under military guard on the Trail of Death. Milliner comments: “While Northerners tend to consider ourselves free from the troubles lately faced by Southern monument culture in the United States, it needs to be remembered that the Midwest currently remembers the events just related with columns of triumph,” commemorating the defeat and removal of Native tribes with memorial columns in Indianapolis and Stillman Valley, Illinois. In contrast, at the terminus of the Trail of Death in Kansas, one finds only crosses, remembering those driven there to die: “If the blood of the martyrs is what makes places holy, the Midwest has holiness to spare.” Milliner notes Chesterton’s observation that pagan monuments in Rome were topped with crosses to recapture them for holiness and remarks, “Perhaps it is the job of the twenty-first-century Christian Midwesterner to, without forgetting the suffering of settlers, imagine our monuments with Indigenous crosses on top.”

Finally, Milliner turns in his third chapter, “Mother of the Midwest,” to an attempt to find a patroness for the Midwest—a depiction of the Virgin Mary that might serve as a northern counterpart to Our Lady of Guadalupe: “But the Virgin I have in mind has the advantage of expressly bringing the stories of the First and Second Nations together. Neither triumphantly Catholic or Orthodox (let alone Protestant), she atones for acrid divisions among Christians that have bedeviled this continent, especially in Indigenous populations.” Drawing upon Chesterton’s late Marian poem The Queen of Seven Swords as well as the history of Marian iconography, Milliner finds within the Native history of the Midwest an icon of Mary as the Virgin of the Passion, or Our Lady of Perpetual Help. Whereas many depictions of the Virgin are triumphant, Our Lady of Perpetual Help is the sorrowing Mary, depicted with the implements of Christ’s crucifixion. Milliner traces the history of this icon, which first came to popularity as “the conscience of the Crusades,” an image especially venerated by Orthodox Christians who suffered as collateral damage in the conflict between the Crusaders and the Muslim states.

In the same way, he notes that the Virgin of the Passion appears in Indigenous Christian contexts under the expansion of the American and Canadian states, “with the same Virgin Mary functioning as an emblem of Native American ‘survivance’ under defeat.” More generally, documenting appearances of the icon in churches of all types across the Midwest, he advocates Our Lady of the Passion as the patroness of the Midwest, representing how reflective Midwesterners might grieve our bloody history but equally redeem it. Similarly, the Virgin in Chesterton’s Queen of Seven Swords serves as a point of unity, bringing together under her patronage not just the warriors of European Christendom, but the church of Africa. Their words of acclaim to the Virgin are poignant: “In all thy thousand images we salute thee. . . . Hewn out of multi-coloured rocks and risen / Stained with the stored-up sunsets in all tones.” And, Milliner notes, the warriors of many nations then lay their swords down. Just as the Virgin in Chesterton’s late poem offers the nations a source of unity and the end of conflict, so Milliner proposes the Virgin of the Passion as a patroness for Midwestern Natives and settlers alike.

In attempting to accurately describe Milliner’s project I have ranged widely across history, culture, and literature, but above all I would like to reader to see that this book is a resolutely personal project. Milliner begins and ends the book with reflections on his own English family history, including his ancestors’ involvement in conflicts with Native Americans and their struggle to ascend to a higher social status in nineteenth-century America, a struggle that at times would have involved them in a vicious conflict to demonstrate that they were truly people—that is, in the parlance of the time, that they were white. And so even in his most analytical, historical chapters, this book represents nothing so much as Milliner grappling with how to live with integrity and justice on this land himself. It is perhaps that personal search for contentment that makes this book a notable contribution to the literature on the American racial problem: Milliner’s “penitent Midwest regionalism” is first of all an attempt to heal within himself the disease and discontentment produced in those of us who have been told that what matters about us is that we are white.

In that light, let me add my own personal note. The authors I discovered as a teenage Anglophile continue to help me love my home. Yet these days I am more and more drawn to the stories that belong more closely to this place—not out of a sense of guilt or obligation so much as because I love Turtle Island and want to know its history and culture intimately. And so I have been drawn especially to literature written by the First Peoples of this place, by Black Elk and Leslie Marmon Silko, N. Scott Momaday and Linda Hogan, Diane Glancy and Louise Erdrich. As I read these authors, I find in them not a means to rebuke my teenage Anglophilia, but a profound continuity with that boy’s longing for a place he could love, a place with a past. And in reading Indigenous authors, I find that place is my home place after all. In that spirit, I would like to give the last word of this review to the Acoma Pueblo poet Simon J. Ortiz, whose poem “Passing through Little Rock” echoes Auden’s lament for place, reading in part:

The old Indian ghosts—

“Quapaw”

“Waccamaw”—

are just billboard words in this crummy town.

. . .

I just want to cross the next hill,

through that clump of trees

and come out on the other side

and see a clean river,

the whole earth new

and hear the noise it makes

at birth.