West Palm Beach, FL. Much has been written and made of the status of “free speech” on college campuses in recent years. Some people are certain that the average university has become a totalitarian and freedom-hating environment. Others are certain that universities have been forced to protect students and staff from an escalation in aggressive and unacceptable speech. Much ink has been spilled describing and analyzing the situation. Some people choose to focus on students censoring themselves, each other, and faculty; others focus on the role of the professionals in the room. Regardless of whom these critics focus on, they tend to zero in on the interactions that occur in one specific place: the classroom.

The classroom is certainly one of the most important spaces on a college campus. It is where the formal learning that adds up to a degree takes place. It is a site of instruction and sometimes of self-discovery. For some students the classroom has become an uncomfortable space for expressing their personal views. Many people are asking hard questions about intellectual conformity in classrooms. When it comes to the classroom, it seems clear that shaming students is not a helpful pedagogical approach.

What is not altogether clear is exactly what role the classroom should be playing in campus speech. There is, perhaps, too much pressure on the classroom to be a place for self-expression. What types of conversation belong in the classroom and when? Students should not be self-censoring in their chairs, but neither is every class session an invitation to open discussion. Students may sometimes lack a clear understanding of the distinctions between different classes and the role of personal expression within them. At the same time, academic culture has, for the most part, abandoned any insistence on formality in the classroom, which permits things to get unprofessional much more quickly.

Faculty, the actual professionals, may also sometimes lack a clear understanding of the proper role of personal expression—their own or others’—in any given class. Faculty have been increasingly encouraged to lead with discussion in nearly every subject, but most have not been trained in managing classroom discussion, much less managing it with empathy. Many professors have experienced a student turning on another classmate during discussion, but almost none of us have had any lessons on how to handle that before we experienced it. Neither are faculty trained for how to respond to students who express direct opposition toward a professor or an established view in the field.

It is unsurprising that classroom discussions can sometimes be challenging and frustrating, if not worse. We have made the campus classroom a site for self-expression and discovery and we encourage discussion of nearly everything. But those responsible for managing that space have little training in actual classroom management and are still responsible for communicating information pertinent to a specific discipline. It has become popular to blame all bad teaching on tenure, but lack of training and insufficient time for these expanding expectations seem to play a larger role in the dissatisfaction with classroom discussions.

In order to work toward a better environment for everyone, we may need to look beyond the classroom and toward other spaces for speech on campus. The rise in concern about free speech correlates quite remarkably with the decline of campus newspapers and college radio. College campuses have fewer newspapers than they once had. Some have gone online; some have gone under as a result of administrative decisions. College radio, once the best place to discover new and obscure music, has become rare. Some stations have been shut down, others sold off. These were budget-based and administration-led decisions, but they have big implications for the speech environment on college campuses.

It is difficult to practice free speech without appropriate spaces for it. Historically, college newspapers have not only fostered campus culture, they have featured opposing views. They have been a space where students can carry on their own discourse, with limited oversight from faculty and administrators. That is a very good thing. College radio has not only provided an origin story for successful bands, it has been the starting point for a number of distinctive voices in broadcasting. The ability to get your own radio show and explore your interests and musical tastes, to learn through doing, is a beautiful thing. It also makes college radio another space for students to express themselves outside the classroom.

The more spaces that exist for exchanging and engaging different ideas, the lower the stakes for each encounter. Once upon a time, classroom debates were perhaps less significant because there were other places for students to engage opposing views. When I was an undergraduate, we had a “Wittenberg Door” on our campus—a bulletin board where students could post all kinds of ideas for public viewing. At many campuses today, they would like to eliminate bulletin boards altogether in favor of screens, with only the announcements approved and posted through campus departments to be permitted. No wonder students are stressed by classroom conversations: so many of the other forums for conversation have been shuttered.

Students are sometimes uncomfortable with a lack of consensus or challenging views, but there is a certain amount that students need to sort out for and among themselves. There’s a scene in the Richard Linklater college movie Everybody Wants Some!! when one of the freshmen on the baseball team expresses some discomfort with the things he’s been learning and all of his new experiences. Beuter just isn’t sure what to make of it all: “it’s kind of confusing.” One of his fellow freshmen tells him, “Who gives a turd what some egghead professor says?” When he’s still unsure, one of the seniors asks him, “Beuter, are you prepared to fold like a lawn chair?” He then comically yells, “Private Beuter, are you prepared to fold like a lawn chair?!” Beuter responds, “sir, no sir.” As an egghead professor myself, I happen to love this. The classroom is intended to be one source of information that provokes students to spirited discussion in other spheres.

The students in that movie can work through those issues together because they have a sense of community. They are all on the baseball team together. Things like campus newspapers and radio stations and student clubs create a sense of campus community and shared identity. If a university is too streamlined or lacks a distinct identity, students may never enter into the “imagined community” of their alma mater. When students feel that they are part of a shared community, they are less likely to turn on each other. And if students can only use social media for self-expression, their statements go out to the whole world, which also raises the stakes for engaging new or controversial ideas. In order to be a “safe space” for speech, a campus needs to be grounded in a sense of place and a mosaic of local discussions.

The issue at hand is not as simple as a tyrannical grip on opinion or expression by a particular party or set of interests, the issue is also about an administrative grip that pursues cost efficiency at the expense of campus culture. Some may be pointing a finger at political correctness, but the budget spreadsheet bears much of the blame. Have we hollowed out the campus experience so that students lack good spaces for self-expression? Why are these the items that can be eliminated from the budget? In saving money, are we strangling campus culture? The classroom cannot bear all the burden for fostering community and cultivating the virtues required for free expression.

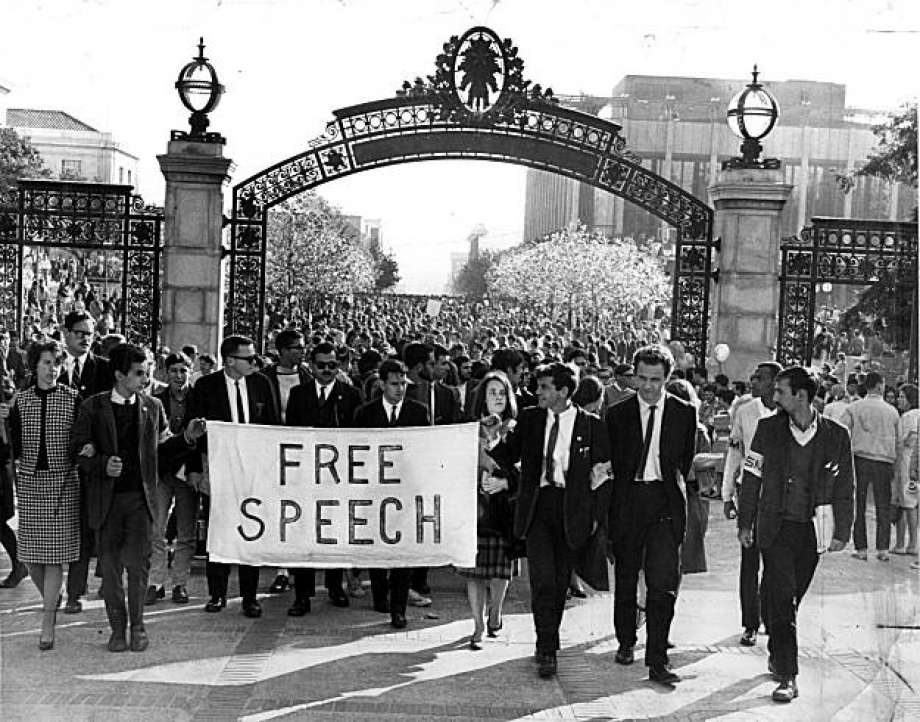

Students could very well demand spaces for discourse beyond the classroom. That is how the Free Speech Movement began in 1964, as described by Louis Menand in his new book The Free World. At Berkeley in the early 1960s, students “had been allowed to set up tables representing political causes on a twenty-six-foot strip of sidewalk just outside campus.” But in 1964, a vice chancellor (Alex C. Sheriffs) walked by the tables and “decided that the spectacle was a bad look for the university.” There was a ban on political activities in that space and soon after students were giving speeches and being arrested. Of course those students were not only insistent on self-expression, they were willing to face imprisonment for it. Students today pay quite a bit in tuition and fees and could ask more questions about where it goes.

Providing students with more outlets for expression will not resolve all of the problems with speech on campus. Reviving campus newspapers and radio stations and student-led clubs, and putting resources behind them, could create more space for speech, help foster campus community, and model a level of comfort with differing views. The classroom may still need adjustment, but antagonistic wrangling with, or under the gaze of, professors is not the path to enlightenment. At the end of the day, instructors are still primarily responsible and qualified for guiding students through disciplinary knowledge. Healthy campus speech requires healthy campus culture with a variety of spaces for expression and exchange beyond the classroom.

Image of 1965 Free Speech March at UC Berkley.

2 comments

Martin

“Some may be pointing a finger at political correctness, but the budget spreadsheet bears much of the blame. Have we hollowed out the campus experience so that students lack good spaces for self-expression? Why are these the items that can be eliminated from the budget?”

People point to political correctness because that is where the money is going. Or to look at it your way (focusing only on one’s cut), those are the programs that are deemed untouchable, or invulnerable to budget concerns.

Numerous writers have pointed out that non-teaching employees now outnumber teachers at most colleges. It is no longer enough to have a Director of the Office of Diversity — as that bureaucracy grew, the army of SJW needed a higher rank, and so a Dean was created and budgeted, and more recently the management has been handled by a Vice President at many universities. A large army needs a general, who not only wields more power but also has a correspondingly higher salary and golden parachute, thereby bloating “tuition and fees”.

Aaron

My impression of my students is that the classroom is perhaps the only venue in which free speech of the type you’re discussing, is likely to happen, even if–and I think you’re right about this–the classroom is not itself always the ideal venue for doing that.

It’s been many years since there was such a thing as a campus paper here, and we just lost our campus radio station last year. Interestingly, the effort to get rid of the radio station was driven by a small coterie of students, who didn’t want to pay the student fees to support it, and the apathy of the rest, who largely didn’t even know that we had such a thing. Students would have to come around even to the idea of listening to the radio, for getting the station back to matter very much. So when much of the rest of student interaction seems to take place over social media, which, it need hardly be said, does not tend to foster productive civil discourse, what’s left? Well, the classroom, which has its own problems, as you rightly point out.

I do often find myself sacrificing course content in order address other types of issues, which is problematic, but I wonder if that’s not the best we can do, to offset the increasingly pyramid-scheme nature of higher ed.

Comments are closed.