Fiesole, IT. Neil Dahlstrom is the Branded Properties & Heritage Manager at John Deere. His research on the histories of agriculture, business, and the press has appeared on The History Channel, PBS, and in a first book about Lincoln and the “President’s Mission to Destroy the Press” as well as in his more recent work on John Deere. His most recent book, Tractor Wars: John Deere, Henry Ford, International Harvester, and the Birth of Modern Agriculture, is another romp of a read about the introduction of that most famous of movers of “modern agriculture”: the tractor.

Tractor Wars starts with the rather familiar stories of the figures and the firms that are featured on its cover: Henry Ford, the “young man with demonstrated mechanical aptitude, limitless imagination, and ambition, [who] left the farm at the age of sixteen for the city of Detroit” (xiv), Cyrus McCormick Jr., the heir to the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company who left Princeton and came into his own as a “ruthless protector of profit” (14) and the President of International Harvester amid the Haymarket Riot and the Merger Movement, and William Butterworth, the somewhat less famous, but, as Dahlstrom tells it, no less formidable, “newcomer” (13) of a man who made the leap from punctilious son-in-law to President of Deere & Company in 1907.

Dahlstrom, who writes with the eye of a novelist as well as an archivist, then follows these figures in their race to design, develop, and distribute their machines across the drama of the first two or three decades of the twentieth-century in the United States. Tractor Wars thus covers events of broad significance in the history of agriculture like the Merger Movement, the First World War, and the Depression of 1920-21 as well as episodes of importance in the history of the tractor like the Winnipeg Industrial Exposition of 1908, the National Tractor Demonstration of 1916, and the Tractor Test Bill. The book and its author are at their best when their focus is trained on the former, such as in the passages on the First World War, when Dahlstrom weaves through a wealth of research on the business that his protagonists conducted on the other side of the Atlantic, including material that will be of interest to students of agriculture in Europe as well as the US.

With a story of such grandiose ambitions as Tractor Wars and a storyteller of such obvious talents as Dahlstrom, the reader might be forgiven for expecting, not just a romp, but an epic, of the kind that have become ever more common across America, Amazon and Netflix, in which two or three titans of business clash in a contest of sweat, tears, and sheer will on the (somehow bloodless) fields of commerce. (And, for readers of How It Works Magazine, AgWeek, and The Wall Street Journal, the book might well fit both of those bills). For readers of the Front Porch Republic, and, as most us are, readers of Wendell Berry, however, Tractor Wars will read less like an epic and more like a tragedy, if not like a brochure at some bizarre museum, filled with the banalities about the “birth” of a broken, and in no sense bloodless, model of modern agriculture.

The first of the banalities that are to be found in Tractor Wars are the banalities—or rather more, the biases—about the “inevitable” (39, 52, 62, 11, 142; with and without scare quotes in the text) in the “birth,” the development, and the replacement of the tractor and the other technologies of “modern agriculture.” These biases are to be found at the level of the sentence, where Dahlstrom slips into the backward logic of lines like how the tractor “required yet another evolution” (41), how various technologies, above all, the horse and the tractor, were “pitted against each other” (224), and how the tractor, in particular, and “power farming,” in general, “made [and make] it all possible” (25, 229). But the same biases are to be found at the level of the book, as a whole, where the author falls back on banal, but no less bold, statements about how his subjects were bent on a “race to revolutionize agriculture” (xiv), rather than a race for markets, about how a “growing nation … could only benefit from a new era of power farming,” (35; my emphasis), and, of course, about how “necessity was truly the mother of invention” (51).

Dahlstrom demonstrates an awareness of the dangers of such biases himself, in one of the welcome but otherwise wanting instances of interpretation in Tractor Wars, when he writes that “nothing is inevitable until it actually happens” (229). “Nothing,” much less the elimination of an entire mode of production in the horse, is “inevitable,” however, not just until it “happens” but, as the content of the book shows so well, until it is made to happen, through the force of what Dahlstrom calls the “contextual drivers” within the “larger political, social and economic climate” (229)—and which are, themselves, made to happen—as well as the power of the still rather small collection of individuals, inventions, and ideas that are featured in Tractor Wars.

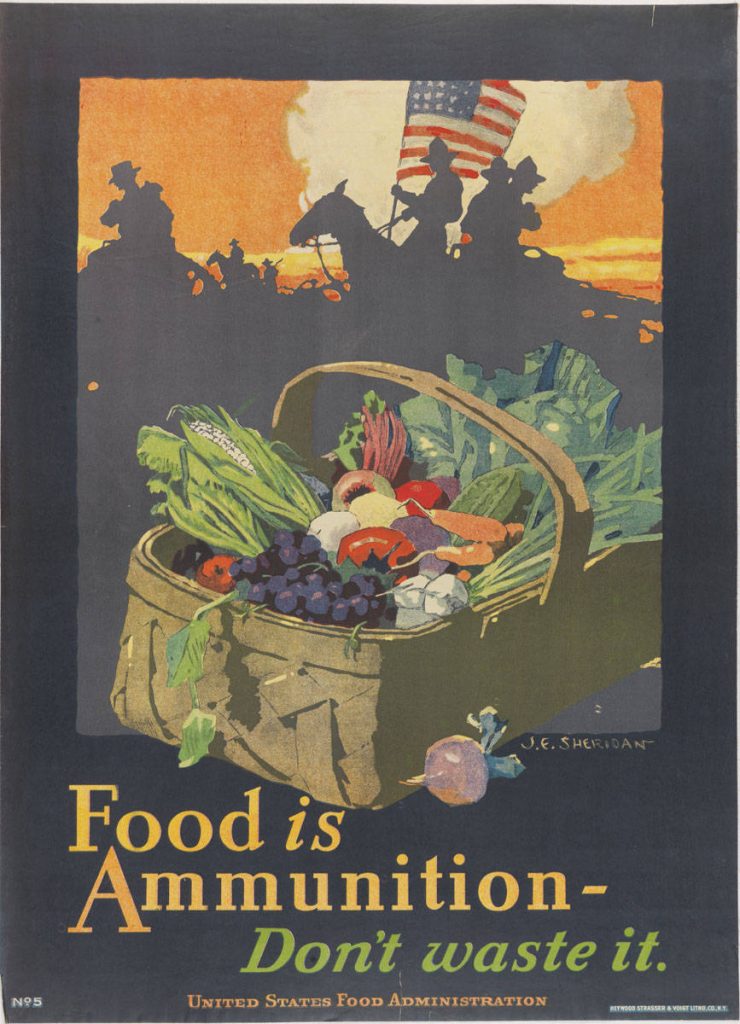

This latter line on context points toward a second in the series of banalities in Tractor Wars, of which the book demonstrates somewhat less awareness. And that is, if not the underestimation, then the misrepresentation, of the power, the force, and, indeed, the violence of the “birth of modern agriculture.” This trend, too, is to be found at the level of the sentence, where Dahlstrom lapses into the language of war and refers to “marketing,” “property,” and “legal” “battles” (15 ,64, 135), to the management of pests as “trench warfare” (158), and, of course, to “Tractor Wars.” But the same can be found at the level of the book, where he writes but one sentence about the American Indian Wars and the Homestead Act (43), none about Reconstruction or the Great Migration, and never enough about the First World War, the fruits of all of which were not just to drive forward the development of the tractor, but to drive people off the land, if not off the face of the earth, as in the “Great War.” Indeed, the “necessity” that Dahlstrom cites as the “mother of invention” in the development of the tractor was less the need for more labor, the need for more food or, more often, the need for freedom from “drudgery” (with and without scare quotes in the text) than it was the need for less labor on the farm, or, in the words of one of his subjects, to “remove drudgery from the farm and CUT PRODUCTION COSTS” (218; all-caps in text) after Reconstruction, the Long Depression, or the Haymarket Riot, and the “necessity,” the “military necessity,” as dubious as well as murderous of an idea as it is, of the First World War.

Again, Dahlstrom, with his subtle flair for writing as well as his serious skill for research, draws the attentions of the reader to this “larger political, social and economic climate,” such as when he trains his focus on the forces within this climate across the First World War and the Atlantic. But one wishes Dahlstrom would have brought these forces a bit more in and out for his audience as “contextual drivers,” and then, perhaps, as the consequences as well as a causes of the “birth of modern agriculture.” And, even if “tractor wars” is the term of contemporaries—in this case, of Cyrus McCormick III—one wishes that Dahlstrom would have done so with different words. For “battle” and “war” have proven not just some of most pernicious of metaphors, but some of the most perilous of metastases of and for “modern agriculture,” from Lloyd George’s “Land Army” to Mussolini’s “Battle for Grain.” Such minor changes might have lessened, or at least explained, the rather hollow, if not shallow, feeling of the “victory” at the end of Tractor Wars.

The hollow feeling with which one is left at the end of Tractor Wars leads toward one of the final banalities of “the birth of modern agriculture,” and that is, what is left out of Tractor Wars, in the broader mass of individuals, institutions, and ideas that, together with those of Ford, McCormick and Butterworth, were behind the “birth of modern agriculture.” Again, other than the reference to the labor movement in the Haymarket Riot and the references to government in the Federal Trade Commission, the Food Administration in the US, and the Ministry of Munitions in England, the reader is left with a number of questions about how John Deere, Ford, and International Harvester would respond to the demands of labor after the Long Depression or the state after the First World War, if not how the three firms would do so in still more recent times, when John Deere has faced similar demands from representatives of farmers in D.C. as well as from unions across the Midwest. Other than the retreat of Ford and the retirement of Butterworth to the Board of Directors, it remains quite unclear, if not somewhat suspicious, too, why Tractor Wars ends in 1928, when Ford, John Deere, International Harvester, and the tractor would drag “modern agriculture,” and with it, the modern world, through the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, the Second World War, the Cold War, the “Green Revolution,” and the shock of the COVID-19 Pandemic. The least that can be said is that this book should be read together with those of R. D. Hurt, Donald Worster, and Paul Conkin, if not of Berry, Maurice Telleen, and Vandana Shiva.

Of course, a history of all of “modern agriculture” is not what Dahlstrom has set out to do with Tractor Wars, and its blind spots might be written off as the products of a book that has been written for a broader audience, if not as a product of John Deere. But to write them off as such would be wrong, not just because Dahlstrom is as a historian as well as a Heritage Manager, but because all of the biases, all of the bloodlessness, and all the banalities of Tractor Wars, I suggest, are the products of a whole way of thinking about technology, agriculture and the economy, one that values invention over implementation or use, innovation over maintenance or care, and the “modern” over the technologies that are proven to work better for the plants, animals and people of the broader communities of agriculture in the present as well as the past. If we are to survive the wars, that is, not just the “tractor wars,” but the actual conflicts over technology, resources and life, itself, with which we are faced in our own time, we will have to think better.

1 comment

Christopher Baird

If we associate work with drudgery, and place the high value that we have over the last several decades on cheap food, then the presumptions of “modern agriculture”criticized herein are necessary. What is needed is a cultural shift: undo the dichotomy between work and leisure, and recognize food as a good and not merely a necessity. The problems have taken generations to manifest, and will take generations to solve.

Comments are closed.