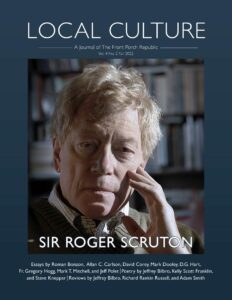

Below is the introductory essay to the new issue of Local Culture, which is devoted to the life and thought of Sir Roger Scruton. To receive the full issue in the mail, subscribe by October 23rd.

People wish to be settled; only as far as they are unsettled is there any hope for them.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Circles”

It is through settling that the most important fund of social capital is accumulated, and an unsettled world will be one in which inherited wisdom will be irretrievably dispersed.

—Roger Scruton, News from Somewhere

Emerson once said that “greatness appeals to the future.” This is one reason Emerson wasn’t great. Another is that he declared himself an “endless seeker, with no past at [his] back”—which is to say the kind of “endless” seeker who seeks in one direction only. He held the botanically dubious view that the roses under his window “make no reference to former roses or to better ones.” He wondered why we “should import rags and relics into the new hour,” inasmuch as “nature abhors the old, and old age seems the only disease.” He went so far as to say that old age is the disease that “all others run into…. We call it by many names—fever, intemperance, insanity, stupidity, and crime; they are all forms of old age; they are rest, conservatism, appropriation, inertia, not newness, not the way onward.”

This kind of unthinking thing some call a thought is all too familiar where the cult of The Future thrives: the campaign trail, college campuses, advertising, and other platforms of prevarication. Newness! The way onward! It is the kind of talk that transforms goods into necessities and sanctions the planned obsolescence that ensures a steady flow of them. Thus the “economy” thrives. We know this because we can see with our own eyes all the busy garbage trucks making room for The New, and pollution becomes our most reliable indicator of economic health.

Consider, by contrast, the structure of Roger Scruton’s News from Somewhere, which bears the subtitle On Settling. It is an account of Scruton, an analytic philosopher of no little renown and stature, taking up permanent residence on an out-of-the-way farm in Wiltshire, England. The chapter titles, in order, are “Our Soil,” “Our People,” “Our Animals,” “Our Home,” “Our Place.” Only at the end of this movement from soil to place does Scruton devote a chapter to “Our Future”—and he does so not as if greatness but as if humility appeals to it. He understood that not to think of the soil, people, animals, home, and place—and not to think of them in order or in relation—is to prepare their ruin; it means that they will be colonized by those in the present who are unwilling to think of them at all, for capitulation to the inevitabilities of “progress” is always much easier than mindfulness of the good things at hand. (Aldo Leopold: “to build a road is so much simpler than to think of what the country really needs.”) And those inevitabilities are, of course, entirely predictable. Scruton noted that “advocates for the global economy,” for example, argue that the global economy itself “is an inevitable development of the capitalist system, and that it will spread freedom, prosperity and democracy around the globe.” But

much intellectual effort is wasted on such half-baked predictions, which are usually not predictions at all, but intentions in the minds of maniacs. By pretending to predict when you are really deciding, you exonerate yourself from blame. You describe your purpose as “inevitable,” “irreversible,” a part of “progress.” Anyone who resists is “anachronistic,” “reactionary,” a victim of “nostalgia.”

Scruton was quick to add that “it was in such unsettling language that the revolutions of the twentieth century were sold to their gullible consumers, and the 1000-year Reich and the socialist millennium notwithstanding, people go on mouthing this trash and go on believing it.”

This isn’t exactly the applause Emerson anticipated in the Lyceum lecture hall when he sneered at “rest, conservatism, appropriation.”

But be assured that the anachronistic, reactionary, and nostalgic dissenters from the global economy, the independent-minded folk with pasts at their backs and roses that descend from other roses, will be footing the bill for the inevitabilities others have decided on. As Scruton noted, the burden of regulations and taxes will continue to fall “most heavily on the small businesses, small producers, small farmers and small shopkeepers,” which means “the part of the economy that is most important to the life of the community [will be] forced underground”—a simple fact of human existence that any child too much hovered-over can tell you. Make him do everything in front of you, and he’ll start doing all kinds of things behind your back. And good for him.

The Emersonian sneer has a familiar feel. Conservatism cannot possibly be good because it is bad. The keepers in that totalizing alliance of commerce, politics, education, and news have said so. They certainly wasted no time stigmatizing Scruton after he published The Meaning of Conservatism (1980). He had become a conservative, he tells us, while in France in the 1960s. He recalls being brought up at a time when “almost all English intellectuals regarded the term ‘conservative’ as a term of abuse.” To be a conservative then was to be a carrier of all the sicknesses that Emerson said old age is a catch basin for:

[it] was to be on the side of age against youth, the past against the future, authority against innovation, the “structures” against spontaneity and life. It was enough to understand this to recognize that one had no choice, as a free-thinking intellectual, but to reject conservatism. The choice remaining was between reform and revolution. Do we improve society bit by bit, or do we rub it out and start again? On the whole my contemporaries favoured the second option, and it was when witnessing what this meant, in Paris in May 1968, that I discovered my vocation.

Scruton recalls seeing scenes resembling those in American cities in recent years: smashed windows, upturned cars, uprooted lampposts, bloodied policemen, and self-righteous young revolutionaries atop the barricades. But they were revolutionaries unprepared to die for their beliefs, only to “put others at risk in order to display them.” The contrast between his own view of the chaos and that of the revolutionaries brought the difficult discipline of affirmation into bold relief—affirmation not of boundaries or institutions but of “language, religion, and high culture,” for “in times of turmoil and conquest it is those spiritual things that must be protected and reaffirmed.”

And so Scruton, who as a teenager had intuited the importance of aesthetic judgement and was now repulsed by the ugliness of the contemporary vandals around him, assumed the vocation of the protector, the conservator. Modernism, especially Modernist architecture, provided the necessary heuristic:

I saw—though I did not have the philosophy to justify this—that aesthetic judgement lays a claim upon the world, that it issues from a deep social imperative, and that it matters to us in just the way that other people matter to us, when we strive to live with them in a community. And, so it seemed to me, the aesthetics of modernism, with its denial of the past, its vandalism of the landscape and townscape, and its attempt to remake the world of history, was also a denial of community, home and settlement. Modernism in architecture was an attempt to remake the world as though it contained nothing save atomic individuals, disinfected of the past, and living like ants within their metallic and functional shells.

So it was that Scruton, convinced that debunkers and defenders alike had misunderstood conservatism, set out in The Meaning of Conservatism—which the keepers of commerce, politics, education and news wasted no time pouncing on—to show that “the conservative attitude, and the doctrine that sustains it, are systematic and reasonable,” that it alone is aware of “the complexity of human things” and attached “to values which cannot be understood with the abstract clarity of utopian theory”—that, indeed, utopian theory tends by nature heedlessly to simplify, and by simplifying to falsify, and in falsifying to destroy all that is at once complex and true and worthiest of preserving. Scruton, in a ponderable but by now unthinkable move that would baffle today’s journalists and academics alike, said that conservatism “may be defined without identifying it with the policies of any party. Indeed, it may be a stance that appeals to a person for whom the whole idea of party is distasteful.” But he was also clear to point out that in his view freedom

is not the precondition but the consequence of an accepted social arrangement…. Freedom is comprehensible as a social goal only when subordinate to something else, to an organization or arrangement which defines the individual aim. Hence to aim at freedom is at the same time to aim at the constraint which is its precondition.

Constraint, that is to say, jars not with liberty, only with liberalism. Thus “Locke, and the other great individualists, who thought otherwise”—and who prepared the way for what Robert Nisbet would call “loose individuals” free of all restraints and responsibilities—“were also constrained to think that the world contained many ‘vacant places’ which could be filled by those who chose to withdraw from their inherited arrangement.” Scruton had little patience for this sort of self-enthrallment:

Is it not psychological naiveté to think that I, now in middle age, rooted in my language, culture and history, could suddenly do a volte-face and see myself as English only by accident, free at every moment of change? If I go elsewhere I take my Englishness with me as much as I take my attachment to family, language, life and self. I go as a colonial or as an exile, and either sink like the Tibetans or swim like the Jews.

The alternative is the self-deceived idea of a “fulfilled human being whose style of life is entirely of his own devising.” This is an observation that derives from Edmund Burke, who, objecting to the French revolutionaries, said that living and trading on the individual’s private stock of reason is foolish; “the individuals,” Burke said, “would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages.”

No wonder, then, that Scruton was possessed of a Burkean distrust of 20th-century revolutionaries:

The great intellectual advantage of socialism is obvious. Through its ability to align itself with ideals that everyone can recognize, socialism has been able to perpetuate the belief in its moral purity, despite crime upon crime committed in its name. That a socialist revolution may cost millions of lives, that it may involve the willful murder of an entire class, the destruction of a culture, the elimination of learning and the desecration of art, will leave not the slightest stigma on the doctrines with which it glorifies its actions or the people who have taken part in them.

In other words, it can dispense with the inherited wisdom of tradition and take up with the folly—which is to say the untried fervor—of the moment. While Scruton’s target here is socialism, his broader point is not a party observation. It is a description and indictment of two opposing inheritors of a single modern doctrine, inheritors who in America we call “conservatives” and “liberals,” “republicans” and “democrats,” “right” and “left”—or who some, not without good reason, call “wrong” and “wrong.”

Roger Scruton was born in Buslingthorpe, Lincolnshire, on February 27, 1944, to John (“Jack”) and Beryl Scruton. He and his two sisters grew up in High Wycombe and Marlow, both in Buckinghamshire, a little over thirty miles west of London. The children endured an embattled relation with their temperamental father, a schoolteacher who, as we are told in Gentle Regrets, hated the upper classes; the children’s mother, Scruton writes, “born and bred in the genteel suburbs of London,” cherished “an ideal of gentlemanly conduct and social distinction” that his father “set out with considerable relish to destroy.”

Early encounters with Pilgrim’s Progress and a collection of Rilke’s letters set Scruton on a bookish course, though his first interests and talents were in the sciences, which he intended to pursue at Cambridge. Upon matriculating there he switched almost immediately to philosophy and graduated in 1965 with a double first. After two years abroad he began work on a doctorate in philosophy at Jesus College, Cambridge, which he completed in 1972. His thesis, supervised by Michael Tanner and Elizabeth Anscombe, was published as Art and Imagination (1974), the first of more than 50 books he would write not only in philosophy but in autobiography, fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. He also wrote two libretti. His work would range widely across aesthetics, religion, politics, culture, farming, architecture, music, fox hunting, wine, and England itself. He founded both The Salisbury Review, which ran under his editorship for almost twenty years (1982-2001), and Claridge Press (1987-2004).

Always something of an academic outcast, Scruton nevertheless held several academic posts. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he was a Research Fellow at Peterhouse, Cambridge. For nearly 20 years he taught philosophy at Birkbeck College, after which he was Professor of Philosophy and University Professor at Boston College (1992-1995). He also held a research post in Virginia. After returning to England and to Sandy Hill Farm in Wiltshire, which he had purchased in 1993, Scruton held a visiting Professorship at Oxford and was a senior research fellow at Blackfriars Hall. In 2010 he delivered the prestigious Gifford Lectures at St. Andrews in Scotland, later published as The Face of God (2012). For three years he held a part-time professorship in moral philosophy at St. Andrews, and at the Birthday Honours of 2016 he was knighted.

And then there were his political involvements, especially during the Cold War, when he worked on behalf of Eastern European dissidents and persecuted intellectuals in Prague, Hungary, and Poland, frequently putting himself in danger by smuggling in books and organizing underground seminars for the Jan Hus Educational Foundation that the Czech dissident Julius Tomin had founded. In June of 1985 Scruton was detained and then expelled from Brno; his name was placed on the Index of Undesirable Persons. In Gentle Regrets he recounts being followed in both Hungary and Poland.

The stories of his first-world persecutions are perhaps better known, chief among them a predictable New Statesman hit job in 2018 by an irresponsible journalist named George Eaton, who accused Scruton, then chairman of the British government’s Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, of the usual crimes against humanity: Islamophobia, homophobia, and anti-Semitism—an especially rich cocktail, given Scruton’s German-Jewish ancestry. Scruton was summarily dismissed from the commission by Communities Secretary James Brokenshire, the same man who had appointed him, when on “Twitter,” that platform of nuance par excellence, several of Scruton’s remarks had been manipulated in order to misrepresent him and destroy his reputation. The perfidy was later exposed in The Spectator, and in July of 2019 the New Statesman was obliged to issue an apology, as was Secretary Brokenshire, who then reinstated Scruton. The affair is worth looking into: it would seem a case-study in illiberal liberalism were it not merely another public display of its official visage. The intolerance can hardly be surprising in an age when knowing languages means nothing and when the clamorous confusion that rushes in to fill the space they’ve been evicted from cannot be quieted or put to rights.

Scruton did not need to think of himself as an international public figure or a “global citizen.” In an essay titled “The Dangers of Internationalism” he admitted that there are certain dangers attendant to nationalism and that being an Englishman made it difficult for him to be a nationalist, there being “no such thing as the English nation.” But he did not demur from thinking of himself as such.

England is the metropolitan center of an Empire that has vanished. My country, defined geographically, is Great Britain; defined politically it is The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; defined culturally it is nowhere and everywhere, the point of departure for the greatest experiment in international government that the world has ever known. Nevertheless, I am a patriot, a believer in local loyalties, and a fierce defender of the territorial and historical rights of my countrymen.

In this same essay Scruton distinguished between the “cosmopolitan” properly understood and the “internationalist.” European art and culture, he said, are cosmopolitan, which is why it is possible for a cosmopolitan to be “at home in any city” and to “appreciate human life in all its peaceful forms.” An internationalist, by contrast, “sees the world as one vast system in which everyone is equally a customer, a consumer, a creature of wants and needs.” He “does not feel at home in any city because he is an alien in all—including his own.”

The cosmopolitan is a nationalist—a believer in his own nation. But he is also a believer in all other nations that have captured a corner of the earth that they can legitimately claim as their own. He is a patriot of one country, but a nationalist of many.

In this sense Scruton himself was both a nationalist and a patriot, and in light of the foregoing it is not difficult to see why he had little patience for America’s not-yet unforgotten (and putatively conservative) meddlers who brought forth on this continent a new empire, conceived in bellicosity, and dedicated to the proposition that all Middle Eastern countries are created equally susceptible of refashioning according to the pattern of Western democracies. Concerning this fool’s errand, of which at the moment we apparently enjoy a temporary suspension, Mark Dooley, Scruton’s literary executor and contributor to this issue, has weighed in. Scruton’s The West and the Rest (2003), Dooley says, has been rightly acclaimed for its sensitivity “towards the sacred rites, rituals and pieties of the Muslim faith.” Given the mere economic costs of interventionism, to say nothing of the human lives it has heedlessly made a quietus of, there is something to be said for being “a patriot of one country but a nationalist of many.”

This issue of Local Culture is devoted to Scruton not because he was a conservative—for by now, clearly, “conservative” (like “liberal”) is not a reliable word—but because he was unique in this sense: he was a philosopher of no few credentials who, in the end, was not so much a philosopher as a man, a man of place and home and family and of the humanizing limitations that place and home and family impose upon the individual who, it turns out, is not “atomized” or “loose” but emphatically social, an I in unrelenting need of a thou—a testament to an old idea according to which it is not good that man should be alone.

If in passing I recommend Scruton’s News from Somewhere, or Gentle Regrets, or England: An Elegy, or Mark Dooley’s Roger Scruton: The Philosopher on Dover Beach, or his Conversations with Roger Scruton, or, as a primer, Scruton’s Philosophy: Principles and Problems, I do so in the interest of opening in the space left to me a small window on the smaller world that this wide-ranging and widely traveled philosopher settled for. For Scruton settled on a farm in Wiltshire and wrote lovingly about it, about its soil and people and animals—and about their reasonable desire to live in their place free of the impositions of distant planners who, caught up in steamrolling abstractions, would flatten all of England’s green and pleasant land into a dull unvarying monoculture. “It is only since becoming part of a family,” Scruton wrote, “that I have become fully aware of the depth and seriousness of the opposition between the family and the State. The family has become a subversive institution—almost an underground conspiracy—which is at war with the State-sponsored culture.” He offered the example of, among others, the “state-imposed lessons in sex education” that in America has not a few of us marveling at such shock-and-awe missions as the Drag Queen Story Hour, which ought to suggest to us how deathless Moloch is and how willingly we will sacrifice our children in the apparently unquenchable flames surrounding the altar of that insatiable god. What is almost as bad is that we do it for no good reason except to avoid the public shaming that awaits us from the keepers of commerce, politics, education, and news.

Or if the drums in the temple aren’t loud enough to drown out the screams in that analogy, take the economic metaphor instead: like good participants in the global economy, acting on orders from its own version of the high priests, we externalize the costs: we send the bill downstream in time. We send it to our children and to our children’s children, who will never have anything like an innocent unsexualized childhood to look back on.

The family, said Scruton, is by now an “‘option’ rather than a norm,” and the state-sponsored lessons “will ensure that the next generation will not form families, since it will have destroyed in itself everything that leads one sex to idealize the other, and so to channel its erotic feelings into marriage.” Scruton lamented that he and his wife, Sophie, “belong to a growing class of dissidents, at war with the official culture and prepared to challenge it. This official culture is founded on the premise that human material is infinitely plastic, and can be moulded by the State into any shape required.” Writing here as a writer rather than as a philosopher, Scruton did not pause to point out—although he might have—that this official culture issues perforce from the modern project itself: once we begin to treat nature as malleable, conformable to human desire, we will move on—and did move on—to assume the same about human nature. This is a far cry from a much older philosophical ideal: that rather than making reality conform to our desires, we should conform our desires to reality. Emerson said “I must be myself”—forgetting an older dictum that would have him know himself.

Of that marriage to Sophie, which death put asunder on January 12, 2020, Scruton wrote:

We become fully human when we aim to be more than human; it is by living in the light of an ideal that we live with our imperfections. That is the deep reason why a vow can never be reduced to a contract: the vow is a pledge to the ideal light in you; a contract is signed by your self-interested shadow.

Scruton, from that day in France until the end, could never situate himself in the fugitive and cloistered comfort of the academic and intellectual orthodoxy. To the life of what Wendell Berry once called the itinerant vandal Scruton finally preferred settlement,

an association of free beings, who treat each other as sovereign. It is the relation on which markets ultimately depend, and it thrives in rural areas because people are compelled to assume responsibility for their own lives, in an economy that places a premium on trust.

The soil in Wiltshire is “curmudgeonly” and niggardly and makes farming difficult for the people who nevertheless intend to continue farming, even though they bear the “unpredictable costs of needless regulations.” They live by cooperation and would never dream of sending a local dispute to a “higher tribunal than local gossip.” Stable marriages aid in the plight of family farms; “fungible partnerships” threaten them. A craft economy survives and “spreads its influence around itself, leading even the incomers to adopt the habit of mending what they might otherwise throw away.” Formal social dancing abides; it “banishes the sexual motive to the background.” Walking home from one you find the dance joining “other dances that have happened on this spot of earth” and you understand that these “moments of intense and purposeless community are the reason why we exist.”

Add dance, then, to the “myths, stories, dramas, music, painting—[for] all have lent themselves to the proof that life is worthwhile, that we are something more than animals, and that our suffering is not the meaningless thing that it might sometimes seem to be, but one stage on the path to redemption.”

— JP