Palm Beach, FL. Alex Jones was recently ordered to pay over $900 million for his perpetration of the idea that the Sandy Hook shooting was a hoax. Properly speaking, the damages were part of a defamation lawsuit related to the harm caused to victims’ families by his promotion of the hoax on his media platforms—years of threats and harassment. Throughout the trial, Jones’s Infowars site was actively denigrating the judge in the case and raising money for Jones. He considers himself the victim of conspiracy and an unwilling participant in a show trial. Of course, the social media responses to the verdict represent a wide variety of opinions. Some people are thrilled that Alex Jones owes people money. Some are saying that freedom of speech is dead in our country. Some have posted that Jones has been right about a lot of things, so… just saying. How did we get here? Where will we go from here?

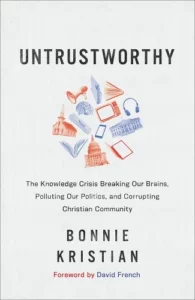

Bonnie Kristian’s new book Untrustworthy wades into these troubled waters. A professional journalist herself, Kristian considers us to be in the midst of an “epistemic crisis.” We seem unable to agree on what is true and unwilling to commit ourselves to the importance of truth. All knowledge seems up for debate, but we no longer engage in true debate, either. This is true in the country generally, but also in the church. She writes that this crisis “is breaking our brains, polluting our politics, and corrupting Christian community. It may be the most pressing and unprecedented challenge of discipleship in the American church.” Untrustworthy seeks to diagnose our current condition and then offer some remedies from a Christian perspective.

Untrustworthy is a clear and compelling book that covers our relationship with media and considers how we can have a healthier relationship with it, the people around us, and the truth. Kristian begins by outlining critiques of the news media, distinguishing between the fair and the unfair. She then examines the culture that has emerged with our current media of all types, including skepticism, conspiracism, and cancel culture. Kristian addresses all sides fairly, without descending into useless “whataboutism.” Then Kristian explores what a healthier relationship to media would look like, with regard to our emotions, our identity, and our epistemology. Lastly, she offers a plan for healthier habits in media consumption and conversation with others. This is a book which has useful advice for people who need to spend less time on Twitter and people who are trying to reclaim family members from QAnon.

Our problems with knowledge have contributed to our problematic politics. Our entrenched positions, determined often by feeling or identity rather than facts, are good only for throwing bombs across the divide. As our shared understanding of truth has declined, our debates have become more contentious. Using the insights of various scholars and the events of recent years, Untrustworthy offers suggestions for how to have honest and open debates. Kristian also suggests ways in which Christians can bring avenues of redemption into present-day controversies, alternatives to the more common practice of public shaming without the possibility of restoration.

Untrustworthy is both thoughtful and practical. Kristian offers reflections on epistemology and useful definitions of the difference between truth, knowledge, and opinion. She addresses the range of issues with the news (not just potential political bias) and successfully differentiates real news from pseudo-news. She describes the troubling rise of conspiracy thinking and the reasons for its appeal. She considers the right relationship between reason and emotion. And at the end of the book, she offers very specific suggestions for healthy habits to counter the epistemic crisis in our own lives.

One aspect of Untrustworthy that is especially appealing is Kristian’s recommendation of developing epistemic virtues. Kristian, like MacIntyre and others, recognizes that the pursuit of virtue is the foundation of many good habits. In this book, Kristian recommends studiousness, intellectual honesty, and wisdom as epistemic virtues we should adopt. We must pursue the truth in the right ways and be honest with ourselves about what we do and do not know. Then we must use wisdom to navigate the gaps between truth and knowledge and the ways in which we interact with others, especially those with different opinions. She then describes N.T. Wright’s concept of an “epistemology of love” and the Anabaptist hermeneutic of obedience—truths are also meant to be lived. Taken together, her vision of epistemic virtues is very compelling.

Virtues require cultivation, but our culture has left us with somewhat untended gardens. We have undisciplined minds, undisciplined debates, and undisciplined media consumption habits. Like other recent Christian books by authors like Jeffrey Bilbro, Justin Whitmel Earley, Alan Noble, and James K.A. Smith (all referenced in this book), Kristian recommends self-examination and cultivation of specific habits—disciplines. Disciplines might seem like restraints, but in his classic on Christian discipleship, Celebration of Discipline, Richard Foster describes each of the disciplines as freedoms. They free us from the “slavery of ingrained habits.” For example, disciplines like taking time away from our phones and committing to knowing fewer news stories more in-depth, free us from the tyranny of constant and somewhat incomprehensible information. When we choose more carefully what we consume and how, we are not buffeted by every wind but are better able to adjust our sails and tack as needed. In the same way, if we have disciplines for our debates and conversations with others, we are freed from the need to have or win every argument by any means and freed from the need to set everyone else straight. These disciplines are not complications to our lives; they are opportunities to be released from burdens we cannot carry anyway.

In Untrustworthy, Kristian sets an objective for Christians to be faithful, factual, and fair. In some cases, this must be practiced in a somewhat extreme environment. What do we do when we encounter something like QAnon, which is not factual and often fractures relationships? What if we encounter it in our own family or our own church, as many do? Untrustworthy helps explain the appeal of conspiracies (and QAnon in particular) and offers helpful advice for reaching across the epistemic divide. While our first reaction may be shock when someone suggests that JFK Jr. is out in the world campaigning for Trump or that Mike Pence might be a clone, our second reaction is usually to attempt to debate the issue. But Kristian reminds us of Chesterton’s observation in Orthodoxy that in such an argument “it is extremely probable that you will get the worst of it; for in many ways his mind [the conspiracist’s] moves all the quicker for not being delayed by the things that go with good judgment.” Instead, Kristian takes Chesterton’s suggestion that our job is to bring fresh air into that person’s mind, “to convince it that there is something cleaner and cooler outside the suffocation of a single argument.” We should engage in redirection and attempt more conversation on more basic realities rather than attacking every conspiracy head on at every opportunity.

At other times, we must be faithful, factual, and fair in more mundane settings. What news will we read or watch while we eat breakfast? What podcast will we wash dishes to? It is easy to slip into whatever is most comfortable, without holding ourselves accountable for being discerning about what we consume and in what volume. Do we inventory our habits and our beliefs? Do we understand the emotional effects we experience from media consumption? Or do we feel that everyone else is always the problem? It may be easier to blame journalists than acknowledge that we are sometimes credulous and sometimes cynical readers. We may consider others to have extreme opinions while we post an extreme amount of political content on our social media.

One of the best features of this book is the responsibility it places on its readers. It is very easy to write a book about how the media has failed us or how everyone is going crazy. Kristian does not fall into an easy castigation of all kinds of media outlets and figures or merely bemoan the existence of social media. We are already familiar with those jeremiads, and it is not our job to sit in scornful judgment on the world. Instead, Untrustworthy reminds Christian readers of their need to be grounded in truth and to be living and acting in love, which includes attaining knowledge. She writes that “we tend to see acquiring knowledge, becoming virtuous, and living in love as significantly distinct projects; knowledge especially is carved out from the other two.” But, turning to 1 Peter, Kristian argues that they are all entangled and “this is an entanglement I think we need.”

Christians cannot sidestep the epistemic crisis. This is both an issue related to individual faith and a problem in our collective backyard. It’s estimated that about 30 million Americans buy in to at least some QAnon beliefs, and there is an above average percentage of evangelicals among them. Where I live, I see quite a few bumper stickers on a daily basis, and it’s not altogether unusual to see some with QAnon phrases or symbols. There are certainly Christians in my county who subscribe to conspiracist thinking. In some circles, Christians are oblivious to the situation or hoping that these problems go away. But in Matthew 10:16, Jesus sent his disciples out among the “wolves” with the command to be as “shrewd as serpents and as harmless as doves.”

In a letter to his wife, John Adams wrote, “I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.” Adams knew that in a stable country, his sons and grandchildren would have the opportunity to excel in more refined fields. If we want a flourishing community (in our country or among Christians), we must attend to foundational things. Few things are more foundational than epistemology.

There is no simple or total solution to our epistemic crisis. Kristian suggests that we begin by looking first to ourselves and our immediate communities. We are capable of making better choices about news and social media and considering knowledge more seriously. To achieve a more grounded perspective, we have to learn to stop ignoring inconvenient truths, in the world and about ourselves. One individual may not overturn the epistemic crisis facing the whole country, but many people adopting healthy disciplines at the same time can have a leavening effect. Imagine a Christian community with grounded epistemology, not drawn into things like Infowars or distracted by cynics or charlatans. Imagine a community with a respect for truth and knowledge and other people. It is worth the effort to make this vision a reality.

This is a book which should be widely read in Christian circles. And there is no reason for it not to be. It is readable and clear. It is honest and non-partisan. It is not merely philosophical, it is practical. It should be welcome in church reading groups and would make an exceptionally good common read at a Christian university.

5 comments

Elizabeth Stice

Sorry for the delayed response, but, yes, I have actually met people who think JFK Jr. is alive and the whole thing. I’ve had someone tell me that many celebrities I think are dead are actively working for Trump. It woke me up to the reality that these are real people and they don’t just exist on servers.

Dan Grubbs

This is also part of what we get as a society that teaches and reinforces that there is no truth and that PR is more important than veracity.

Brian

“While our first reaction may be shock when someone suggests that JFK Jr. is out in the world campaigning for Trump or that Mike Pence might be a clone”

Have you actually ever had this happen? I read some pretty obscure corners of the internet, where I first heard all the facts about the RussiaGate hoax, about who Jeffrey Epstein was, etc., and I have literally never encountered anyone who talks about or believes anything about anything related to “QAnon”.

Aaron

Brian:

I don’t know what counts as obscurity on the internet, but the guy who fixes my dryer when it breaks painted his entire shop in a Q theme, and appears to be headed to federal court pretty soon, as regards his role in the capitol fracas. This particular example, illustrates, I think, the importance of the whole FPR ethos, as far as actually knowing people, as opposed to extra-local caricatures of them. Do I think Q is cracked? Yep. But my appliance guy is a really nice guy, and I’d be poorer for not knowing him, too.

Aaron

Brian

What does “a Q theme” mean?

(re: the “capitol fracas”, if he hasn’t gone to federal court in the last 21 months, then I’m sure he did absolutely nothing even remotely illegal by any sane standard.)

Comments are closed.