Siloam Springs, AR. Centuries ago, devotion implied a commitment to God, a dedicated piety. We are devoted when we give of ourselves, to God and to others. For many of us, our devotion is an understood part of our teaching or parenting philosophy. We give time to prepare, think, plan, and collaborate to benefit our students and our children. Some call devotion “giving it your all” and see it as a standard of excellence. Others call it a virtue.

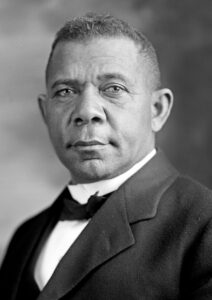

That’s how I would describe the steadfast quality in Booker Taliaferro Washington. Beginning in the 1880s, on almost every Sunday evening at Tuskegee Institute, Washington collected his students, teachers, and visitors to speak to them. The gathering wasn’t called a chapel service or a Bible study, it was simply “Sunday Evening Talks.”

Even if he didn’t have each student in class, as an educator, Washington was determined to shape the character and lives of all Tuskegee students in a whole education, not just head-knowledge. His devotion to education and to the people who surrounded him in his work was clear. Week in and week out, he gave time to them. Washington said this was because “Unless you have got truth, you have failed in your purpose to be educated.”

In these evening talks, Washington speaks of practical education, the trades, and working with our hands. He addresses qualities such as self-reliance, obedience, justice, and responsibility in order to study the nature of man. He mentions disappointments, homesickness, difficulties with people, and the danger of success but adds that we must always be aware of opportunities, seeing life as a series of opportunities:

And so you will find it all through life, especially for the next fifty or one hundred years, that those persons who are going to be constantly in demand, constantly sought after, are those who make the best use of their opportunities, who work unceasingly to become proficient in whatever they attempt to do.

On February 10, 1895, Washington poignantly illustrated the position of his students this way. He explained coming out of slavery as coming out of a sickbed where a man had been for a long, long time. The sick man would recover given time and opportunity, but he would have to learn again how to use his muscles, how to eat, how to function and work. Placed side by side with a healthy man, the sick man had a long way to reach his full strength. It was a process that required patience and persistence–one might even say devotion. And this was an investment he knew well.

In his autobiography Up from Slavery (1901) and again in his biography of Frederick Douglass (1906), Washington describes the lasting irony of abandonment, a people who must suddenly depend on themselves as the Civil War ended. In Up from Slavery he writes that

most of the coloured people left the old plantation for a short while at least, so as to be sure, it seemed, that they could leave and try their freedom on to see how it felt. After they had remained away for a while, many of the older slaves, especially, returned to their old homes and made some kind of contract with their former owners by which they remained on the estate.

Dependence was normal. Freedom was not. No matter how long it took, the sick man in Washington’s metaphor, his people, had to become well to reach independence. More than mere patience, Washington knew from his own experience that the newly freed slaves needed to be equipped in practical and in moral training. It was a lifelong catalyst that fired his devotion:

Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top.

By 1902, a collection of Washington’s “Sunday Evening Talks” was published by Doubleday as Character Building: Being Addresses Delivered on Sunday Evenings To the Students of Tuskegee Institute. The booklet read, “The speaker has put into them his whole moral earnestness, his broad common-sense and, in many places, his eloquence. Many of Mr. Washington’s friends have said that some of these addresses are the best of his utterances.”

In the talk “Helping Others,” for instance, Washington speaks to all of us, and particularly to teachers and students:

This institution does not exist for your education alone; it does not exist for your comfort and happiness altogether, although those things are important, and we keep them in mind; it exists that we may give you intelligence, skill of hand, and strength of mind and heart; and we help you in these ways that you, in turn, may help others. We help you that you may help somebody else, and if you do not do this, when you go out from here, then our work here has been in vain.

We have been given much and we give in return. I think, I know, that Washington exemplified a whole-hearted devotion to his students. He was concerned, as I am, to educate the whole person of the student, not merely to train children to someday earn a good salary or support themselves. He purposed to equip and to invest in them, to prepare them for the many realities of life that they would walk through at school and beyond.

4 comments

Christine Norvell

Washington’s descriptions center on freed slaves who had little to no skills, those who could barely support themselves. In the late 1800s, Tuskegee Institute offered practical training in housecleaning, gardening, farming, and tool repair as part of its teacher’s school.

Martin

I agree. The sick man analogy and your own emphasis on independence of spirit are excellent. However, it would be good to understand in more detail his notion of practical training: was it specifically oriented toward newly emerging skills?

I ask this because several historians this century have pointed out that the manual labor done by slaves included carpentry and other skilled labor. Some have said that this was part of the resentment that accompanied emancipation: many white men and women in the south had very few hands-on skills. The richer ones were plantation owners and the poorer ones were taskmasters of the slaves, giving orders without necessarily having any other skill of their own.

Mark Botts

Christine, thank you for this essay. Washington’s illustration of the sick man needing to build up his strength is a moving and clear picture. It advocates devotion, as your essay notes, and patience.

Also, the following lines from Washington are powerful: “we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top.”

Christine Norvell

Thank you for reading!

Comments are closed.