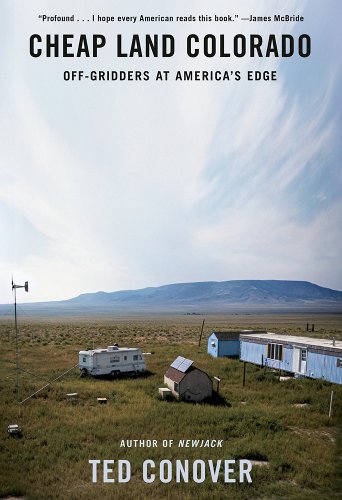

West Palm Beach, FL. To own a piece of land and to do as you wish with it has long been part of the American dream. The desire to go to some seemingly (if not really) empty and not entirely regulated place and forge something of your own was part of the frontier thesis advanced by Frederick Jackson Turner. Many people today think that there is nowhere left outside of the mainstream, but there are always margins and stretches of wilderness. Ted Conover’s newest book, Cheap Land Colorado: Off-Gridders at America’s Edge (2022), takes us to the San Luis Valley to acquaint us with the people who experience America from its edges.

While some writers find their work isolates them from others, Ted Conover’s projects take him into the most interesting and disparate experiences and relationships. His first book was Rolling Nowhere: Riding the Rails with America’s Hoboes (1984). He gathered his material by riding the rails himself and interviewing people he met. Then he wrote Coyotes: A Journey Across Borders with America’s Mexican Immigrants (1987). To learn about illegal border crossings, he made one. Since then, he has written about guarding Sing Sing Prison (New Jack), about roads (The Routes of Man), and many other things. His approach involves two significant and not elementary aspects: immersion and empathy. Not only has his work won him a Guggenheim Fellowship and made him a Pulitzer finalist—it has also given him connections in unlikely and unusual circles.

As a professional writer and part-time professor at NYU, Conover is an outsider to the outsiders in Colorado, but his immersion and commitment help him overcome that barrier. For Cheap Land Colorado, Conover first went to the San Luis Valley in 2017. He kept going back, off and on, for months at a time…for years. This pattern has so far not ended. He purchased his own land and trailer and intends to keep going back, even now that the book is published. During his time in Colorado, he has worked to meet neighbors and make friends, and he has also volunteered with La Puente, a rural outreach organization that also has a shelter.

The San Luis Valley is not the part of Colorado where every recent college graduate seems to want to go. Out on the flats, there are few trees and the land is dry and the mountains are not very close. There is a different kind of beauty, a beauty that could be appreciated by someone like Edward Abbey. And on five acre lots, living in trailers and small homes, off the grid and on the fringes, there are people pursuing the kind of freedom from society and social norms that Christopher McCandless pursued. But for all the romantic associations with untamed land and untamed people, the flats are also a hard place, where many rely on disability or assistance, most people are missing teeth, seemingly everyone has COPD, drugs and guns are common, and opportunity is scarce. People burn their trash and chain their dogs and are always tangling with law enforcement for lacking septic systems.

Some people end up in the San Luis Valley seeking something, others are running from something. Conover writes:

Generally speaking, the flats residents I met were not the young and idealistic (though there were exceptions). Rather, they were the restless and the fugitive; the idle and the addicted; and the generally disaffected, the done-with-what-we-were-supposed-to-do crowd. People who, feeling chewed up and spit out, had turned away from and sometimes against institutions they’d been involved with all their lives, whether companies or schools or the church. The prairie was their sanctuary and their place of exile.

Conover describes the people and the land in a way that is sometimes startingly honest. He doesn’t shy away from describing drug use, poor health, criminal backgrounds, depression, conspiratorial thinking, and a dedicated gun culture. If someone is a murderer or child abuser or runs a puppy mill, Conover doesn’t leave it out. But neither does he omit the helpfulness and friendliness of his neighbors, the network of care and assistance he experienced, the local wisdom and impressive knowhow, and the beauty of the sunsets. Sometimes in the flats, horses starve for lack of food and people shoot at each other too quickly, but sometimes people heroically save strangers from freezing to death in the cold or save their friends from themselves. There are people who can fix just about anything and survive on almost nothing. They have reasons to be proud of their resilience.

Cheap Land Colorado partially fits into the broader discourse about red state/blue state divisions and conspiracy-thinking in our country. Some of Conover’s neighbors believe in the sovereign citizen movement. They don’t have driver’s licenses, they are wary of capital letters. Most of his neighbors believed Covid was either a hoax or exaggerated. Many refused to get the vaccine, some of them died. Several of his friends are doomsday preppers. Though not the main point of the book, this worldview is a prevalent part of life in the flats. Coming from a different place and political perspective, Conover identifies the differences but does not villainize his neighbors. But he cannot help but sometimes be surprised by their credulity and concerned by the ways these beliefs further alienate them—making it impossible to maintain legitimate employment, keeping them away from needed healthcare, and making some of them dangerous to others.

B.J. Novak’s recent film Vengeance (2022) takes on some of the same issues. The main character, Ben Manalowitz, finds himself in rural Texas, trying to make a podcast about the death of a young woman named Abilene. The police say she overdosed. Her brother says she was murdered. As Ben investigates, he learns about the local drug trade and Mexican gang, inadequate policing, the lack of opportunity, the beautiful landscape, the affection of a large family, and the love for Whataburger. He discovers that rural America, and its people, are much more complicated than he realized. A charismatic local record producer, Quentin Sellers, suggests that the conspiracies and desperation aren’t signs of inadequacies on the part of residents. He tells Ben: “The problem isn’t that people aren’t smart. The problem is that they are. If the landscape is like this and people were just boring, you wouldn’t have this problem. The problem is that you got all these bright creative lights and nowhere to plug in their energies. So it gets channeled into conspiracy theories and drugs and violence.” In many ways, Conover’s book makes the same point.

Cheap Land Colorado takes us into the experience of people in America who are up against it. Sometimes it’s their own fault. When Conover struggles with some of the help given in his neighborhood and by La Puente to people with not just bad track records, but current criminal situations, he remembers that “the needy are not always the good.” But there are also people who just want to be left alone and have a lot of animals and live their own way without much money. The San Luis Valley is such a place. The right to move away and leave everything behind is at the heart of the American story. The ability of people with little money to have a little land is part of our mythos. When Conover first asked to volunteer with La Puente, someone explained to him that “those with the frontier mentality are trying to make it on their own.” And “the fringes of society really define who we are. They are the extreme fringe, asking questions about how we should all live.”

Toward the end of the book, Conover identifies an overarching question: “Who is America for, and who is it not?” There will always be people who would rather risk the cold than come into society. But reading Cheap Land Colorado makes you wonder how we can make more space for human flourishing among the poor and on the edges of society? Conover’s approach to the San Luis Valley might offer us a starting point. He worked to build friendships and he offers assistance. He drives around offering people firewood for La Puente, gives people rides, and helps out at the shelter. Conover’s help may not solve the structural problems, but that’s not exactly the point. He’s not just there to change the situation. He is there to be connected. And he now has his own lot in the off-grid community.

1 comment

Michael Martin Serafin

I have never read Mr..Conover,’s work, but, he sounds like the non-fiction counterpart to Cormac McCarthy.

Comments are closed.