As a mental health and substance abuse psychotherapist, reading The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution, by Carl Trueman, provoked reflections on the provision of psychotherapy in America today and, more specifically, my experiences as a therapist over several decades. This is not a review of that book; rather, it is giving credit and gratitude for his analysis of the rise, and perhaps regretfully, the “triumph” of the modern self.

Much recent attention has been given to the “mental health crisis” in the United States, arguably more acute than in other societies, with special mention often given to the somewhat unique angst of adolescent girls. Statistics about the prevalence of depression (the “common cold of mental illness,” as it is sometimes called) and anxiety in teens and adults are usually put forth alongside observations about the dearth of mental health providers and psychiatrists, unacceptably long waiting times for even minimal levels of service, and anecdotes of individuals being housed in hospital emergency rooms for days, if not longer, while beleaguered social workers search for available inpatient psychiatric beds. And all of this despite the proliferation of innumerable teletherapy platforms and “warm lines” available to people of all ages, offering psychotherapy and text and chat support from the privacy of one’s home.

The Bishop of Hippo (also known as Saint Augustine, he of Confessions renown) tells the story of a childhood experience in which he and a group of friends carried out a late-night raid on a neighbor’s garden with the intention of stealing pears, circa A.D. 397. As he later reflects, the pears were in no way appealing to him or his friends; in fact, the pears from his own garden were much better, and they ended up feeding the stolen pears to pigs, having a good laugh at the whole thing.

Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions, book 1, written just about 13 centuries later, tells a story with a similar theme: a local journeyman named Verrat persuades the youth Rousseau to steal asparagus from Verrat’s mother’s garden so that he can sell it for profit. Rousseau obliges and provides a subsequent self-analysis of his motivation for committing this act, as well as many other examples of his escapades over time. Rousseau’s assertion that his “psychological autobiography” as a writing form had no precedent was undoubtedly a dismissal of Augustine’s earlier work and, by using a parallel tale, serves to counter Augustine’s reflection on his behavior and provides a counterpoint perspective on his own.

Both men are considered giants: Augustine in the theological realm and Rousseau as a preeminent Romanticist. These simple stories offer us lessons not only on their views about the nature of humankind, but also on how one might understand the experience of psychotherapy today.

While the reference to these tales is inevitably reductionistic and certainly to a degree simplistic, the key contrast between Augustine and Rousseau is this: while Augustine acknowledged a “social” component to his behavior, he reflected upon it as evidence of the fundamental sinfulness of human nature and subsequently felt innate shame, whereas Rousseau attributed his behavior solely to the influence of others, evidenced by his susceptibility to social pressure, stating in book 1, “At first I would not listen to [Verrat’s] proposal; but he persisted in his solicitation, and as I could never resist the attacks of flattery, at length prevailed.” Neither man “needed” the ill-gotten gain, and both recognized that the “satisfaction” derived only from committing the act itself. Most simply put, Trueman, in his summary of these contrasting stories, states, “Augustine blames himself for his sin because he is basically wicked from birth; Rousseau blames society for his sin because he is basically good at birth and then perverted by external forces.”

A central Trueman thesis is that the inevitable result of Rousseau’s contention that the darkest aspects of the self are shaped by the corrupting influence of the society and cultural milieu is that modern persons come to live life through “therapeutic ideals and expressive individualism.” Trueman is not using the term “therapeutic” in reference to “therapy” per se; rather he means that the individual can only find full expression and “authenticity” by shedding any sense of connection to the larger world and seeking a perpetual state of psychological well-being. The natural consequence of Rousseau’s thought, in Trueman’s view, is the politicization of many key cultural developments of the past several centuries, finding their current expressions in issues such as Supreme Court decisions related to marriage, LGBTQ+ and transgender concerns, and the illiberal atmosphere pervading academia. Indeed, Trueman believes that the inevitable endpoint of Rousseau’s thought has found its victory in the emergence and cultural pre-eminence of the “modern self,” that is, one whose entire psychological well-being is grounded in an individual’s particular “identity,” however fluid or ill-defined this may be in any given moment.

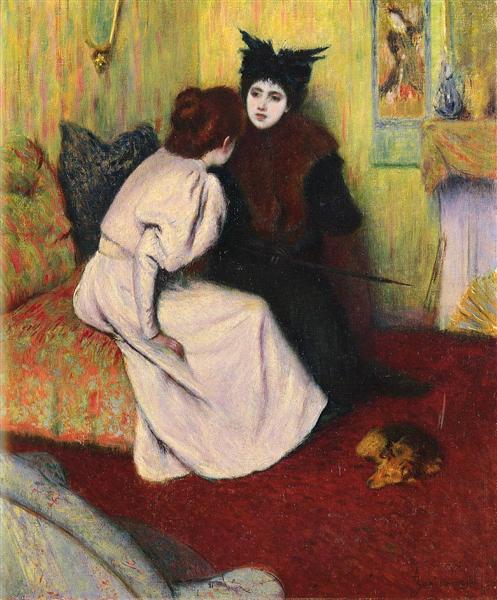

Trueman’s primary thesis is applied to his examination of “the triumph of the erotic in art and culture, . . . the triumph of expressive individualism and related therapeutic concerns in law, ethics, and education, and . . . the triumph of transgenderism as the latest logical move in the politics of the sexual revolution.”

I offer an additional consideration related to an area Trueman does not address: the experience of psychotherapy. This is an environment where the “modern self” might be fully observed, to the extent that any “self” can be observed in the transactional conversation that is psychotherapy. Throughout my professional life I have witnessed how individuals who seek psychotherapy see themselves in the context of their world, whether that be the world of their family, marriage or relationship, or larger community. To the extent that one can say there is a “typical” individual who seeks psychotherapy, it is generally a person who experiences some degree of discomfort or dissonance with the “self” he or she is, and has tried, to no avail, to solve these concerns as a self, using only internal resources.

A therapist’s typical question to a new client is, “Why now?” The answer to this (perhaps to the layperson) obvious question begins to reveal why the individual has been unable to “solve” or “resolve” the self’s concerns from internal resources, i.e., previous efforts at resilience or problem-solving. As noted above and with some exceptions, most individuals seeking therapy today do not differ significantly from individuals at other cultural moments; they experience perceived depression, anxiety, or some constellation of relationship concerns. But what happens next is perhaps the most prognostic of all, determining in large part whether the individual is likely to benefit from therapy at all; the individual’s sense of where the responsibility for the self’s troubles is to be found: “within” or “without?”

With the exception of individuals who are constitutionally unable to accept any responsibility for changing their behavior (narcissistic) and those for whom the basic structure of “conscience” is missing (antisocial or sociopathic), most adult clients, even among us moderns, would identify with Augustine; regardless of aggravating social influences, and indeed needing to recognize and acknowledge them in any clinical situation, the onus for change can only come from the individual’s internal sense of responsibility and personal agency. In this context it is not necessary to accede to the notion of “original sin,” as Augustine would, but rather the sense that only “I” can fundamentally change my orientation and adaptation to the world within me and the world outside of me.

But what of the locus of this sense of “responsibility,” whether it is perceived by the individual as coming from “within” or “without?” In 1991, Charles Taylor writes in The Ethics of Authenticity, of “malaises of modernity,” one of which is “individualism.” Taylor suggests that such individualism (for his purposes finding its genesis in the 18th-century Enlightenment) is the fruit of a distorted understanding of identity. Taylor explains that Augustine’s profound interior explorations aimed at a true understanding of God. Augustine “saw the road to God as passing through our own reflexive awareness of ourselves.” Rousseau’s “self-determining freedom,” on the other hand, “is the idea that I am free when I decide for myself what concerns me, rather than being shaped by external influences.” Taylor’s thesis that the elevation of the modern identity of the “individual self” as necessary for a sense of “authenticity” ignores the historical (one might say long gone) understanding that the true self is most fully realized when it is understood and defined by a sense of belongingness to a community, with all of the consequent accountabilities. For Augustine, this community ultimately derives from God, and it’s only in conversation with God that Augustine can come to know his true, authentic identity. And even Rousseau—like many rebels throughout history—forges his gesture of rebellion out of his reading of Augustine.

Taylor argues, furthermore, that even those who think they can extract an authentic self in purely internal fashion are mistaken. We come to understand ourselves in dialogue with others, and we can either navigate this dialogue deliberately and responsibility, or we can thoughtlessly pick up fragments from our various communities and carry around a disjointed, unexamined identity. “Community,” in this sense, may be understood to mean familial, social, faith, and even political connections that serve to bind us together, and this process of formation occurs no matter how much we try to withdraw into the inner echo chamber often understood to be the “self.”

While many individuals who pursue therapy for the first time often have unrealistic and at times magical expectations for what therapy can do, most come to the process with the implicit awareness that they are looking for “something” to move them beyond their current state; otherwise, why pursue it at all? This is no small thing. The guided conversation that is the essence of therapy is, when it works best, not an echo chamber in which the therapist simply reflects upon and reinforces ingrained but unhealthy behaviors, ideas, and patterns of communication within relationships; no, the challenge of therapy is to empathically identify and confront the client’s concerns, explore alternative ways of viewing the world and his or her place in it, and ultimately move beyond the “painful familiar” to the new and unknown, but ultimately more satisfying, self. Clients often report this journey as most rewarding when they come to realize that the only thoughts, emotions, and behaviors they can change are their own, despite very real and traumatic life experiences they’ve received from the world around them. By taking responsibility for this identity-forming conversation, they come to recognize connections and relationships that run deeper than the reflections from the mirror on the wall.

Even in our modern age, then, it seems that Trueman’s “modern self” as narcissistic echo chamber, unconstrained by relationships with family and community, has not entirely triumphed after all.

6 comments

Rob G

~~it seems that Trueman’s “modern self” as narcissistic echo chamber, unconstrained by relationships with family and community, has not entirely triumphed after all.~~

Very good piece, and as one who has witnessed the benefits of solid counseling/therapy, I agree with much of it. But could it not be argued that the “modern self” has perhaps triumphed everywhere except at the level of the discrete individual and his or her ability/willingness to opt out of the narcisstic echo chamber? I doubt if Trueman would say that his argument applies to each and every individual person to the same degree, so wouldn’t the sort of “moving beyond” you describe be an exception proving the rule, therefore? That some people achieve sainthood doesn’t negate original sin, after all. I say this not in an attempt to throw cold water on your thesis, with which I largely agree, but more as a suggestion that we not take the existence of Trueman’s “modern self” lightly as a result.

Art Kusserow

Thoughtful and respectful consideration and perspective. Thank you for taking the time to read and respond!

Rob G

Thank you, Art. By the way, I’m from Pittsburgh and I know and appreciate the work of PPI.

Art Kusserow

Thanks so much, Rob. And that you mention PPI specifically.

Chris

Excellent. Thank you.

Art Kusserow

Appreciate your read of the piece!

Comments are closed.