Lebanon, NJ. I’ve never really left the classroom. After college, there was graduate school, then becoming a teacher, then more graduate school (while teaching). Just recently another new school year began, though this time I ventured from K-12 education to a university. On our first day together, I found myself a little bit in awe of the students on my rosters. Why are you pursuing higher education, I asked them? In the AI age, in the teach-yourself-on-YouTube era, when influencers make millions of dollars, what are you seeking here? There were answers focused on skills and careers, but what really surprised me was the number of students who said they were seeking relationships and a community in which they could explore the questions they have—about themselves, the world, and God.

“A god we can understand is a god less than ourselves,” Flannery O’Connor said. I shared this quote with my students on our first day of class and then used it to frame our syllabus for the semester. In other words, I was warning the students to start getting comfortable with mystery and with what is unknown. They understood this. Not a single eye rolled. It hit me, after class, that the students entering college now are probably very used to the unknown, the unprecedented. They have something to teach me about this. I certainly still have a lot to learn about not simply tolerating the uncertainties in my own life, and not becoming overwhelmed by them, but instead letting them teach me how to love better, how to love what is difficult and let that shape me.

In fact, I’ve often asked myself (and others have asked me): why teach? It’s not that I think the system of education is perfect—there’s a lot of debate over what style of pedagogy is best, or what content should be included in a curriculum, or which methods of instruction truly foster cognitive development, or even what the goals of an education should be. In these messy, uncertain times, why teach then? In all sincerity, I’ve often answered this question by saying that I think it’s what I was made to do. What else would I do?

As we mapped out the semester, I explained that we would be tracing the questions that have persisted throughout the centuries, in every culture, about what it means to be human and about the best way to live. In the classroom, I get to teach students about the great thinkers who have asked these questions and tried to answer them. I get to guide students as they puzzle through these questions themselves, and not only try to understand what others have thought and concluded, but what their own answers might be—and how to live those beliefs.

This brings to mind Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Letter Four” in Letters to a Young Poet:

Have patience with everything unresolved in your heart

and try to love the questions themselves

as if they were locked rooms

or books written in a very foreign language.

I keep teaching because I love the questions themselves, difficult and frustrating though they may be. And though I’ve just met them, my students seem drawn to pursue higher education for the same reasons. They have questions. They want to see what others before them have thought and then think through those same questions with their peers. I think they know that the world will keep having questions for them—even when they become engineers, lawyers, accountants, nurses—or whatever economic role they assume. But for now, they want to wrestle with questions about the best way to live, for not to decide is not an option.

What can I offer my students, if not answers? Of course, there are some things that are empirical. There are topics I can explain, definitions or histories or strategies I can help students to understand. Students move through higher order thinking levels until the knowledge is their own and they can do something with it. But even Bloom’s taxonomy has at its highest level the verbs that have to do with creation: to generate, to devise, to plan, to prepare, to integrate. Once they know what the questions are, the students can live them, even love them, and let them propel what they create from their lives.

The course I am teaching is part of the university’s core curriculum. Core comes from the Latin word for “heart,” I told my students. The same Latin root, cor, gives us the word, courage, I added. Why might the courses at the heart of the university’s curriculum require courage? I inquired. It’s up to us to decide if we have the courage to accept what is challenging, they wrote. It takes courage to be uncomfortable, to be open, to adapt. With courage, we can pursue what is good for ourselves and others, one student said. It takes courage to stand up for what you believe, said another. Stepping into the unknown requires courage, they agreed. It takes courage to ask questions, to have faith.

I’ve taught in several major cities—Chicago, New York City, and Philadelphia. After living and teaching in all of these places, I find myself back in my home state. It feels fitting to me that, as I settle into this career that I was made to do, I would do so where I grew up. In some ways the fact that I became a teacher, and the fact that I now find myself in New Jersey once again, remain minor mysteries to me. Perhaps this is because it was not my own will that brought me to any of these experiences and places. Perhaps it’s like Rilke says, and I have arrived closer to that “someday far in the future / you will gradually, without even noticing it / live your way into the answer.”

For me, at least part of the answer must be that the classroom is my home, and the world is my classroom. I can learn about the world, and keep asking questions about it by starting with the particular in my own home state. What is the best way to live? The best way to live is to be with others, asking questions, trying to live the answers with courage. And a classroom is a pretty good place to do all of those things.

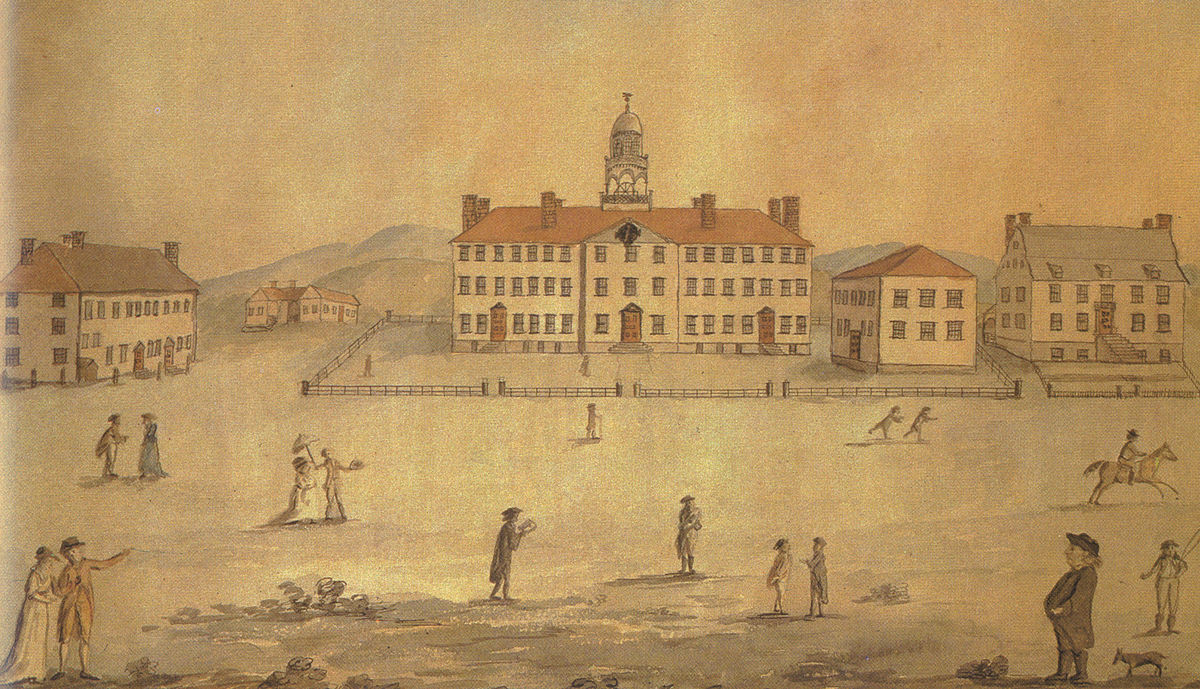

Image credit: “Dartmouth College Campus” via Wikimedia Commons