A new issue of Local Culture: A Journal of the Front Porch Republic is heading to the printer. Below, you can read the editor’s prefatory letter. The Table of Contents can be viewed here. If this whets your appetite, you can subscribe to the journal; subscribe by Monday October 16 to receive a copy of this issue in your mailbox.

But be contented when that fell arrest, Without all bail shall carry me away, My life hath in this line some interest, Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

— Shakespeare, Sonnet 74 (1-4)

Henceforth I call you not servants; for the servant knoweth not what his lord doeth: but I have called you friends; for all things that I have heard of my Father I have made known unto you.

— Jesus in the Gospel according to St. John

“Without friends,” said Aristotle, “no one would choose to live, even though he possessed every other good.”

If the Stagirite is right, as I suspect he is, then what will become of the man who thinks he can be cryogenically preserved until Science figures out how to warm him up and download into him the data he mistakenly believes consciousness can be reduced to? Let us venture a guess. It will be this man’s good luck to discover that immortality on the terms he seeks isn’t in the cards: he won’t have to thaw into a joyless no-place from which all his friends are forever fled.

You may argue that he would make new friends in this fabled future fantasy. But what is friendship stripped not only of long acquaintance but also of the places that its sacred rites were once performed in—this particular fishing hole or that golf course or the hospitable kitchen with the island made of hard maple and the gin-laced gossip that passed across it? What is friendship devoid of the old familiar music halls and fireplaces and barns and deer camps?

And what are these without the friends that make them memorable? What are these without the friendships worn smooth by time’s gentle rolling current?

Edwin Arlington Robinson proffered a pretty good answer once. You will find it in the poem “Mr. Flood’s Party.” It’s about an old man, Eben Flood, whose misfortune is to outlive everyone he knows—everyone, that is, except himself, the self he sometimes talks to on his journey home from filling his companionable whiskey jug in Tilbury Town. Find the poem and read it. It is very funny. It has Robinson’s distinctive touch: treating our often dark solitary condition with good humor and compassion. We may smile at the sight of Mr. Flood out on a dark road, offering himself a drink and then accepting his own offer—and instructing himself not to drink too much (though he already has). And we should smile. The poem means for us to smile. But its ending is no joke. Mr. Flood, alone, his way illumined only by a harvest moon, hears a “phantom salutation of the dead” ringing from “the town among the trees, / Where friends of other days had honored him.” Once he has had his conversation with himself, once he has taken a drink for auld lang syne—a phrase his voice falters on—and especially once he has shaken his head in an effort to clarify the landscape and reduce to one the two moons he sees in the night sky—once he has done all this he returns to his loneliness, or rather his loneliness returns to him. The party is over. He knows it, and so do we:

There was not much that was ahead of him, And there was nothing in the town below— Where strangers would have shut the many doors That many friends had opened long ago.

“We’ve each a darkening hill to climb,” says the speaker in another of Robinson’s poems, and old Eben Flood is climbing his. But like the man who would be frozen into eternal life in the here and now, Mr. Flood is friendless, and we have it on good authority that no one would choose to live without friends, even though he possessed every good thing. This includes a full whiskey jug, which, as it turns out, can neither honor a man nor open a door to him.

I’ll admit to some trepidation in devoting an issue of Local Culture to the second greatest gift the gods have given us. (The first is wisdom, or so said Cicero.) An obvious danger is that we can overthink a thing and in doing so underthink it. And too often we murder to dissect. What’s to stop us from doing the same with that high grace that united Jonathan and David, or Achilles and Patroclus?

We know, if only intuitively, that in a real sense criticism completes art, that going to the trouble of knowing a poem means that we will be able to return to it as better listeners, as indeed once we know what Beethoven was up to in the Eroica we will find that it astonishes us all the more. We will at once hear and know.

On this view friendship may also be an art that invites our probing, if also by inviting resists it. Careful study of any great work of art gives way to knowledge, and knowledge, when it is more fully grown, presents to us by way of return a greater mystery than we started with. Our knowing sends us back to the thing, and we find that it is now larger, deeper, more vexing, if also paradoxically to some degree better known. In attempting to reduce a thing to the terms of our understanding we find it irreducible, a mystery as slippery to the mind as quicksilver to the touch. We have stepped into a wardrobe, and soon the coats are tree branches, the mothballs snow. Inside that tiny thing we find a vast country where it is always winter and never Christmas. We have gone deeper in and found ourselves going higher up as well.

So it is, I think, with talk of friendship. And, at any rate, who can resist the urge to study this creature, Man, the glory, jest, and riddle of the world, and what it is that brings him into the glorious salutary estate of friendship?

Worrying only a little about how we murder to dissect we can avail ourselves nevertheless of the great documents on friendship that in part compose our cultural inheritance. I mean Cicero in De Amicitia and Aristotle in the Ethics, which I have already borrowed from. I mean the works of Plato, Epictetus, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Sir Thomas More. I mean Michel de Montaigne and Francis Bacon, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Immanuel Kant, Hannah Arendt, and Friedrich Nietzsche, to name only a few who have written intelligently and provocatively on friendship.

But what making a list does is remind you of what a bad idea list-making can be. Who would deny the embarrassment of riches in our literary inheritance? For this reason I mentioned old Eben Flood—with the reminder that he isn’t anywhere but somewhere, uphill from Tilbury Town. And who would discount the majority of Shakespeare’s sonnets, which provide an unparalleled commentary not only on friendship but on what it means to be a friend? It was the great bard who imposed upon himself the bold imperative, “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments” and then in a flourish of agnominatio went on to declare that

Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove.

Love, he said, is “an ever fixéd mark / That looks on tempests and is never shaken.”

It is the star to every wand’ring bark, Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken. Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle’s compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

Inasmuch as our means of communication have become increasingly abstract, and given our disastrous inclination to turn a blind eye on the ill-effects of our vaunted mobility, our ideas about friendship, already so cerebral, already so clearly grounded in the airy space of the affections, might play fast and loose with the “marriage of true minds” and slip easily, drowsily, into a kind of gnostic void.

Let us therefore give place and time their due. The young friend for whom this sonnet was written wasn’t cryogenically preserved from the age of Virgil or Boethius. He happened to be walking about not anywhere but in or about London, and not whenever but in the late 16th century. It was he, not just anyone, whom the bard loved and enjoined to marry and beget children. And so it is no stretch to say—though hearing it will sound all wrong—that without him, not without Shakespeare but without the friend, we would lack a king’s ransom in verse. Time and place make contingent the friend no less than the bard. “We think we have chosen our peers,” C.S. Lewis wrote, but

in reality, a few years’ difference in the dates of our births, a few more miles between certain houses, the choice of one university instead of another, posting to different regiments, the accident of a topic being raised or not raised at a first meeting—any of these chances might have kept us apart.

Allowing for this we might be more inclined to acknowledge the fishing holes and barns and kitchens where friendship lives and sometimes dies. I myself can scarcely think of one particular period of intense friendship from long ago without recalling the taps and the SUNY Binghamton grad (an English major!) who tended them, the arrangement of tables and the lighting in that dim university-town watering hole; I can scarcely forget what was maybe the damnedest thing about it all: a pay phone in the men’s room. Many broken promises about arriving home soon were made on that phone as the grip of friendship and the conversation that Aristotle said is its sine qua non took hold of long evenings and dragged them into the early morning hours.

But having given place and time their due, let us also bear in mind how distinctive Shakespeare is in the English belletristic tradition. He is the poet of friendship nonpareil, singular is his capacity to express friendship as a totalizing concern for the friend. If the lines I used as an epigraph above don’t serve, where the speaker imagines his own death as a “fell arrest” that no bail can be set for, think of these lines:

No longer mourn for me when I am dead Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell Give warning to the world that I am fled From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell.

Why the imperative not to mourn?

I love you so That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot, If thinking on me then should make you woe.

Of those sonnets, some hundred and twenty-six of them, Lewis said he could find “no real parallel to such language between friends in sixteenth-century literature”:

The greatest of the sonnets are written from a region in which love abandons all claims and flowers into charity; after that it makes little odds what the root was like. They open a new world of love poetry. . . . The self-abnegation, the “naughting,” in the Sonnets never rings false. This patience, this anxiety (more like a parent’s than a lover’s) to find excuses for the beloved, this clear-sighted and wholly unembittered resignation, this transference of the whole self into another self without the demand for a return, have hardly a precedent in profane literature. In certain senses of the word “love,” Shakespeare is not so much our best as our only love poet.

We could do worse than follow the Roman statesman in thinking of friendship as a divine behest, an endowment we have been charged with stewarding for increase, as in the parable of the talents. Cicero rightly said that “virtue holds friendship together” and that “Nature gave us friendship as an aid to virtue, not as a companion to vice.” So nearly does a pagan claim, as did St. James, that “every good and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father of lights”! That a capacity for friendship my result in the Lyrical Ballads is one thing. But that it might culminate in a last supper hosted by a peaceable rabble-rouser in Palestine is another—one reputed to have said, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

So I come, fearfully, to my second epigraph and also to shakier ground. There is something at once jarring and disarming, arresting and comforting, in that statement recorded by the beloved disciple: “Henceforth I call you not servants,” Jesus says, effectively disrupting the classical notion of friendship between equals, “for the servant knoweth not what his lord doeth: but I have called you friends; for all things that I have heard of my Father I have made known unto you.” What could it mean that God declares man his friend and not his servant?

You might marvel, as I sometimes do, that any old sermon jockey would dare to explicate this of a Sunday morning—or any young sermon jockey.

Hear, then, St. John Chrysostom, who in his commentary on St. John’s gospel says that “to speak of secrets appears to be the strongest proof of friendship.” Jesus says that his disciples have “‘been deemed worthy even of this communion’…. Then He putteth also another sure proof of friendship, no common one. Of what sort was that? ‘Ye have not chosen Me, but I have chosen you.’ That is, I ran upon your friendship.’” A few lines later St. Chrysostom adds,

Seest thou in how many ways He showeth His love? By telling them things secret, by having in the first instance run to meet their friendship, by granting them the greatest blessings, by suffering for them what then He suffered. After this, He showeth that He also remaineth continually with those who shall bring forth fruit; for it is needful to enjoy His aid, and so to bear fruit. “That whatsoever ye shall ask of the Father in My Name, He may give it to you.”

I cannot read this without recalling St. Matthew’s “lo, I am with you always.” Nor does the commentary suffer from comparison to Cicero, who said,

Even when friends are absent, they are still present…. And—though this is more difficult to say—when friends have died, yet they are still alive in you. So powerful and real are the memories of true friends, so great and tender is the longing for them, that even in death they are a blessing and live in us.

If you took away the bond of goodwill from the world, no house or city could stand, nor would the fields any longer bear fruit. If that statement is difficult, then consider the power of friendship by looking at the effect of its opposites, dissension and discord. What house is so secure, what city so firmly established, that hatred and division cannot destroy them? By this fact you can judge the good of their opposite—friendship.

And on this score, to the theme of the abiding friend in Cicero and the deathless God-friend of the fourth gospel, I would add—I would be remiss not to add (though I am skipping over Canto XII of the Paradiso:

Illuminato and Augustine are here; they were among the first unshod poor brothers to wear the cord, becoming friends of God)—

the amicable variation elaborated by Elie Wiesel in that long quest of his to locate God amid the horrors and atrocities of his youth. And what Wiesel came to at last was a character in his fiction he named “Pedro,” a mysterious God-like invention who first appears in The Town Beyond the Wall, which is a remarkable story about friendship amid persecution. And Pedro, far from being silent or absent or both (or, what is worse, hanging dead from the gallows as in Night), does not wait for your release from prison but goes there with you. In Twilight, when you find yourself in the asylum, you find that he is there with you also. And what he recommends by both precept and example are the offices of friendship as the means of making God incarnate.

Tradition tells us that St. Theresa of Ávila also said as much.

The bar and restaurant of that intense friendship I spoke of are gone, and their passing duly lamented. But I think perhaps there’s a lesson in that lamentation: place and friendship alike enjoin their mutual preservation. The placeless and the friendless don’t think so, but you who are right would be doing them a favor by telling them that they are wrong.

And, while you’re at it, tell Cryogenic Man that he is in fact a maniac—from μανία (madness, inspired frenzy), the root of μαίνεσθαι (to rage, be furious, be in a frenzy), as if you’re a certifiable maenad. Name a maenad who has friends. Name a maenad who is one.

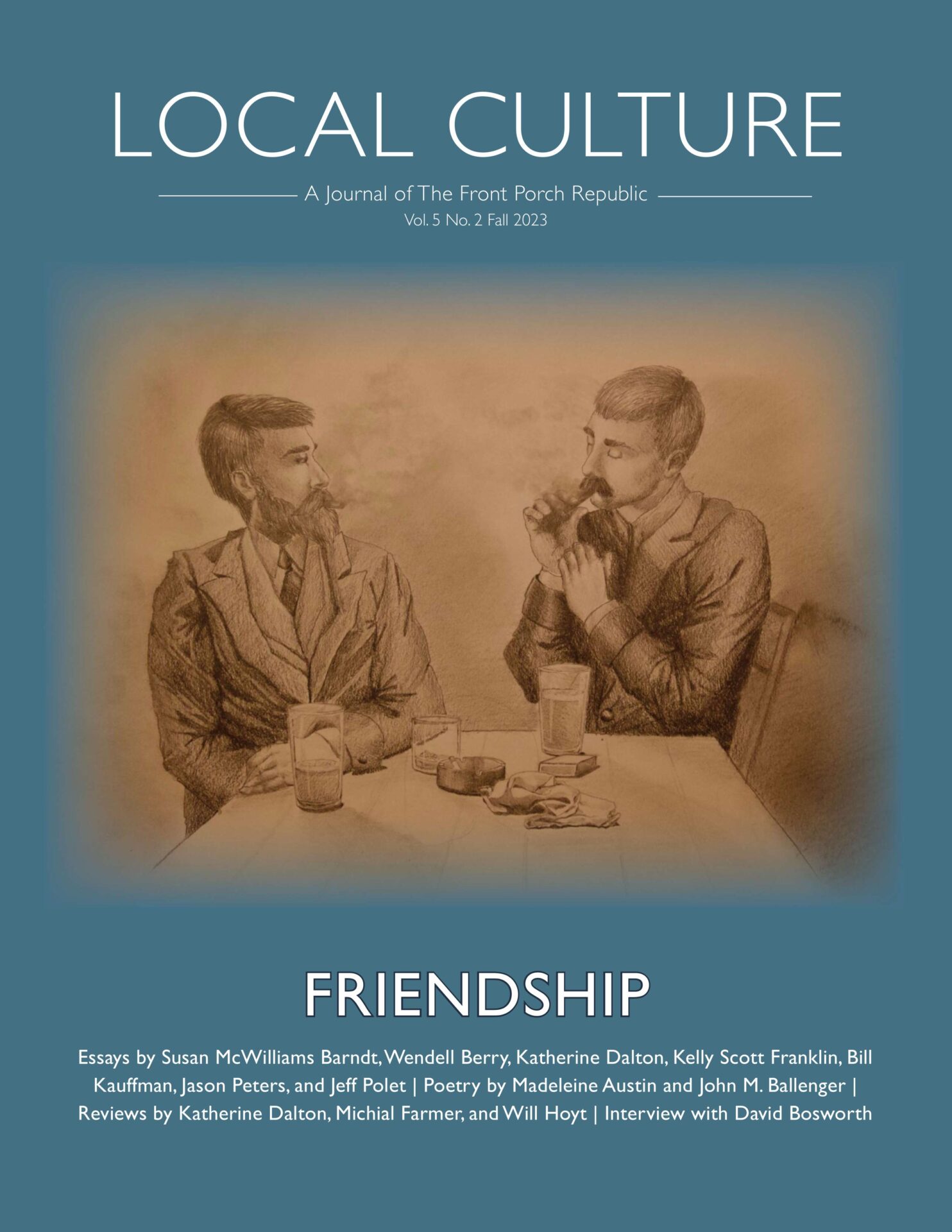

I would like to recognize Ali Westra, the designer and typesetter of Local Culture, for the fine work she did in putting together the first eight issues. The feat is even greater when you consider that she had to work with an editor who, at least in the beginning, had no idea how to put out a journal. Ali has decided to step down, and so on behalf of everyone at FPR I offer her my best wishes and sincerest thanks for her dedication, professionalism, and hard work.

And at the same time I am happy to welcome Carolyn Howell into the role of designer and typesetter and to congratulate her on this, her first effort. Carolyn’s artwork appeared in LC Vol. 5, No. 1 (Food & Drink), and it adorns the cover of this issue. She hails from Miesville, Minnesota. I was fortunate enough to have her as a student at Hillsdale College and also to entertain her and a handful of her classmates on my small farm last spring once the semester had finally come to an end and they had all recovered—more or less—from graduation. They helped me put in my garden, and Carolyn proved to be an excellent driver of the tractor. Thanks, Ali, and welcome, Carolyn.