The following is an edited version of an address delivered at Eureka College’s 2023 opening convocation ceremony.

“May you live in interesting times.” So goes an ancient Chinese proverb, which, like my mother’s antique chinaware, is neither ancient nor Chinese. As we sit back and survey our times, I think it safely can be said: request granted. Our times be interesting.

Of course, outside of moments such as these, when my kids and students and, on this occasion, you the members of the audience, are obliged to listen to me wax philosophical, all times are interesting—or ought to be, at any rate. The fact that there is something rather than nothing is interesting—profoundly so. The fact that we, that you, are part of that something is also interesting—profoundly, miraculously so. Or again, at least ought to be.

We humans are a curious lot, at once capable of apprehending the wonders of existence and, in the blink of an eye, losing sight of them altogether. This peculiar propensity is especially pronounced in this age of universal haste, with our attenuated attention spans and insatiable appetites for distraction.

But even by our modern and, I would contend, superficial standards, these times are emphatically interesting. That there are more than 8 billion of us on the planet today is interesting.

It took untold millennia—thousands upon thousands upon thousands of years—for the world population to reach a billion. After that watershed, it took little more than a hundred years to add another billion. That staggering feat is dwarfed by the proliferation that followed: over the next 100 years—so from last century’s Roaring Twenties to this century’s Raging Twenties–the global population increased, on average, by 1.2 billion people every 20 years.

So eight billion of us inhabiting a planet that ain’t getting any bigger makes for interesting times. But of course it goes far beyond that.

Artificial Intelligence, which heralds our deification or dehumanization; our emancipation or subjugation; our salvation or decimation (depending on whom you’re listening to), promises to keep our times interesting.

COVID-19 certainly made for interesting times and will continue to do so for some time yet. The virus itself may have dissipated, but the effects of that pandemic, as well as the response to it—the extraordinary measures taken to combat it—will be with us for the long haul.

Escalating tensions and turmoil abroad render these times interesting; so too the growing bitterness and discord at home.

On that note. #45. He who cannot be named. President Voldemort. Love him or hate him—there would appear to be no alternative—a Donald Trump on the national stage makes for interesting times.

As these examples suggest, interesting times are often precarious and tumultuous ones. Indeed, that gets us closer to the substance of that not-so ancient, not-so Chinese proverb, which is colloquially known as the Chinese curse. If someone says to you, “May you live in interesting times,” they are not wishing you well. The spirit of that curse can be gleaned from a veritable Chinese proverb, one that dates back to the early 17th century, which reads: “Better to be a dog in times of tranquility than a human in times of chaos.” As a dog lover, who has cared for a number of dogs over the years, I’m inclined to think it is better to be a dog simply, but we’ll leave that for another day.

There is a lot that we are free to choose these days—how we dress, where we live, whom we associate with, what we believe (choices that are so commonplace for us that we lose sight of the fact that for most of history, those seemingly elemental choices could not be made freely, and still cannot be in much of the world today)—but one thing that remains beyond our power to decide is the age into which we are born. All of us are tossed into this world; none of us gets to choose where we land. But if we cannot choose the times in which we live, we can choose how we live in the time we are given. Will we do so thoughtfully or heedlessly? Courageously or cravenly? Honestly and honorably or falsely and deplorably?

Admittedly, I have struck a rather somber tone with these opening remarks, one that might be tantamount to a dereliction of duty on my part. As I see it, the task I have been assigned is to welcome you; to lift your spirits, not sink them. To encourage, not discourage you. To inspire you—not to inspire terror in you (I’ll save that for the classroom), but to inspire you to stay the course which you effectively embark upon today.

So permit me to refill the glass I have too precipitously drained. Not all the way, that would be unbecoming of me. But enough to reach that point of equilibrium, where one could, with equal validity, say the glass is half full or half empty. When I’m done pouring out my thoughts, you can decide for yourselves which half preponderates.

Were I to ask why you enrolled in this institution, I would wager that some of you would say you had no other choice or no better choice; that your parents compelled you to go to college and threatened you if you opted not to—perhaps with getting a job or paying rent or moving out of the house—with growing up, in short. (As one who is routinely told by his better half to grow up, I sympathize with your predicament.)

Some of you, if we’re being transparent, will say that you’ve come here to play a sport: football or basketball or rugby (in which case—that latter one—I’m sorry to report, you’ve come to the wrong place).

The majority of you, I feel confident, would, in some form or another, give the following answer: I’m here to increase my earning potential. A fine reason to be sure, one that reflects the utilitarian spirit of our day. And unlike the aspiring rugby players among you, you—aspiring increasers of earning potential—have come to the right place. I don’t mean Eureka, per se, though Eureka certainly fits the bill, but to college.

The data on this varies, but as a rule, it is estimated that with a bachelor’s degree, your earnings will be roughly 75% higher than they would be with only a high school diploma. To put that in another perspective: over the course of a lifetime, with a college degree in hand, you will earn, on average, over a million dollars more than you would in the absence of one.

Talk about incentivization! There’s the encouragement, the inducement, the inspiration that this address had been wanting. If I had more earning potential and could afford to replace it, I’d drop the mic right about now. Alas…

Yet, to leave it at that would, in my antiquated and non-utilitarian view, still be a dereliction of duty.

Increasing one’s earning potential is all well and good, but to view a college education solely or even predominantly in that light, diminishes the quality and import of that education. An education should do more than increase your earning potential; it should increase your potential outright. It should not just prepare you for earning a better living but for living a better life. Ultimately, it should enrich you in ways that money never can, however fanciful or farcical that may sound.

We might better appreciate the nature of this education by reflecting on the type of college you find yourselves at. You have matriculated at what is known as a liberal arts college, which in some ways is a distinctly American institution. In this country, by conservative estimates, there are more than 200 liberal arts colleges; Illinois alone has more than 20. The vast majority of countries out there do not have any and those countries that do have some, don’t have many. Excepting Canada, no other country has more than 10; that is, Canada aside, no other country has half as many as IL, which itself has half as many as some other states—PA, for example, which has nearly 40 liberal arts schools. There are more liberal arts colleges in the state of PA than in all of Europe.

What is a liberal arts college and why are they primarily found in this country?

In our hyper-politicized day, one hears the word liberal and naturally assumes that it has a partisan connotation. Liberal means on the left; progressive; aligned with the Democratic Party.

But that is not what liberal means in this regard. A liberal arts education is un-partisan—anti-partisan, even—and is so by design; its purpose in many ways is to transcend partisanship.

A partisan is someone who maintains a strong and oftentimes unreflective adherence to a particular cause or party or idea. While this can lend itself to a deep commitment and willingness to sacrifice oneself for that cause or party or idea, it tends to promote parochialism and in extreme cases fanaticism. A partisan will have no problem pointing out the errors of other people’s ways but will labor in vain to detect the errors of his own.

A liberal arts education is intended to show us the errors of our ways; or to frame that differently, to show us that in the ways of others—ways we reject or ridicule or never even imagined—wisdom may be found. And that our own cherished ways are very much open to question, notwithstanding our studious disinclination to ever question them.

A liberal arts education then is meant to be liberating; it is meant to liberate those who pursue it from the prejudice and delusion that exist in every age, our own included. We all harbor certain beliefs, values, opinions, which we did not exactly give ourselves. They have been inculcated in us, not maliciously or mendaciously, but because that’s how we operate. We can’t just start from scratch and figure it all out. We do not have the time or the motivation or the capacity to create our own values; to devise our own moral code; to inscribe our own tablets of good.

None of this is to suggest that your values are flawed. They very well may be principled and just. But the point is that you cannot know this unless you scrutinize them. Unless you ponder them. Unless you weigh them judiciously. And that entails considering and weighing judiciously values that are not your own, competing values, antithetical values; values that may disconcert you, that may offend you, but values all the same that others uphold with a conviction commensurate to your own.

That is what a liberal arts education invites you to do. It doesn’t tell you what to defend, what to fight for, what to hold dear. It exposes you to the musings, the teachings, the works of others; to those who have devoted themselves to reflecting on our shared human condition, on what it means to be human. Those profound and lofty souls habitually do not agree with one another—an enduring testament to the complexity of human beings. But invariably they shed light on some aspect of our condition, and in doing so, they allow us to better understand ourselves.

In ranging far and wide across the vast and varied terrain of human thought, we challenge ourselves, we expand ourselves, and we free ourselves from the narrow confines in which the unnurtured mind is predisposed to dwell.

That quest demands a lot from those who undertake it. In addition to the considerable time and effort it calls for, it will require you on occasion to step out of and leave behind your so-called comfort zones. Indeed, it could be said that that mind is freest which wanders furthest beyond its comfort zone without losing itself. It can be an unsettling and perilous venture. No doubt there is comfort in complacency, just as there is bliss in ignorance. But if that is the sort of comfort and bliss you are after, then I reckon, like the rugby players among you, you find yourself at the wrong place.

So… broadness of mind: that is the sort of good I alluded to earlier; an inestimable good that a liberal arts education engenders. It is good for many reasons, though here I’ll put forward only two:

For one, it conduces to concord, both within and without. A broad mind is not quick to anger, hasty to judge, nor eager to punish. In part this results from an awareness that the riddle of existence is insoluble. The broad mind doesn’t presume to have all the answers; to know what it does not know; and it will want to comprehend better where others are coming from before dismissing them—or canceling or deplatforming them (to employ the not-so-interesting parlance of our oh-so-interesting times). Moreover, the broad mind recognizes that we humans have been at this a very long time; that in spite of our best efforts (and worst), we have yet to figure it out; and that even if we ever did, we would always remain at risk of going astray.

It is human to err. Even the broadest minds are still errant ones. But they know as much.

As a result, they are understanding and patient with others. While they have no illusions about the depravity that lurks in the recesses of the human breast, they maintain that misdeeds are more likely to be the result of misguidance than malevolence. Which is why they are more inclined to instruct than attack; to improve than to harm. I already have alluded to two individuals who exemplify this spirit: Socrates and Jesus. I might add a third, one much closer to home, who occupied his own emphatically interesting times: Martin Luther King, Jr.

If I may hazard a provisional answer to that question raised above—why are liberal arts schools found predominantly in America? It is because the health of the republic depends on a critical mass of citizens who are broadly and liberally educated. An expansive, pluralistic society devoted to ensuring that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth cannot long endure without that critical mass. Self-government requires broad and liberated minds, much as despotic governments depend on narrow and fettered ones. Perhaps part of the present rot in America can be attributed to the decline in the quality of education in this country and to the plight of the liberal and liberating arts in particular.

Two, broadness of mind gives you room to grow. I trust each of you has a lot of life left ahead of you. For better or for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, you’re stuck with you until death do you part… and perhaps—what do I know, what do any of us know—long thereafter. Better to be stuck with a capacious you than a cramped one. Just as a plant without room to grow will atrophy, so too will the human mind. The more inner depth and breadth one embodies, the more likely one is to flourish in this life. And it is the flourishing soul that knows the sort of well-being that money alone can never afford.

If you’ll indulge me, one more point I’d like to get across. It regards the voguish denigration of privilege.

For much of history, privilege was seen as a good thing. It was reserved for the few, who guarded it jealously; it often was envied by the many, who longed for and never tasted it. In our day, privilege has become a term of opprobrium, of contempt. Nobody wants it or wants to admit they have it; those who do have it are eager to shed it—or give the appearance of shedding it—in rituals of public expiation.

At the risk of raising hackles and ruffling feathers (and let me add as a relevant aside: education is unproductive without the occasional provocation), I would argue that if you find yourself where you are today, you are privileged. I don’t wish to seem insensitive. No doubt some of us have more privilege than others; and I don’t say any of this to slight the very real trials and tribulations that each of us faces. We all have our crosses to bear and some of those crosses are much heavier than others.

Still, the ability to receive an education, to acquire knowledge and autonomy with it; to express your views openly, even unfashionable, heretical ones, of the sort that, in an earlier day, might have landed you in hot water (figuratively and literally); to contest the authority of those in authority, be they living or dead—that is a privilege, one that has been reserved for an exceedingly small number of people throughout history and still is denied to many today. I implore you never to lose sight of that.

For now, I wish you all the best. May your time at Eureka be wonderfully enlightening, richly rewarding, and interesting, but not too interesting.

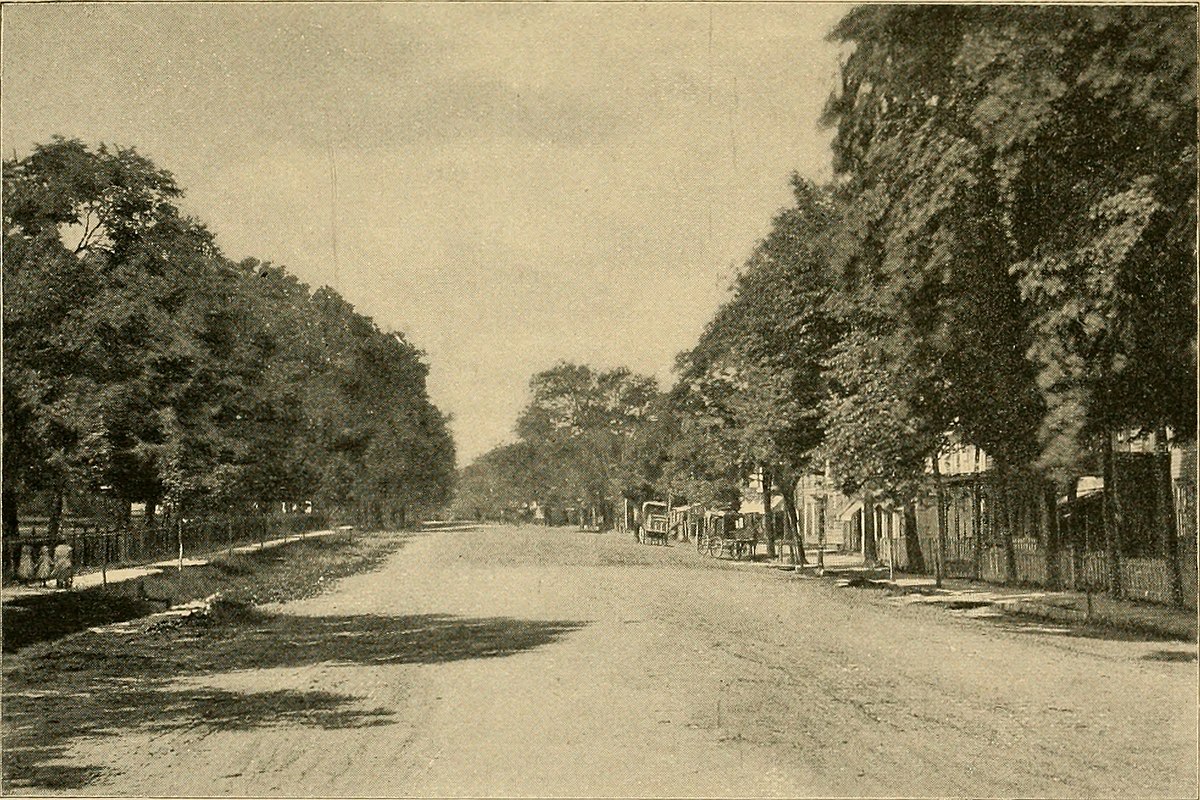

Image credit: “Princeton Sketches” via Wikimedia Commons