In the spring of 2017, Brandi Levy failed to make the varsity cheerleading squad at her Pennsylvania high school. Upset with the decision, she went to a local convenience store and dashed off a SnapChat message that targeted some offensive language at the school and its extracurricular activities. Some teammates took a screenshot of the message and showed it to their coach, who suspended Levy from cheerleading for a year. In 2021, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that the coach violated the First Amendment (Mahanoy v. B. L), liberals applauded the decision for challenging authority, vindicating student rights, and protecting speech critical of the government. The American Civil Liberties Union started selling t-shirts with Levy’s message on the front.

Mahanoy may have been legally sound, but the decision itself is nothing to cheer about. If anything, it reveals the danger of treating schools as governmental rather than associational or fundamentally educational institutions.

Media coverage of Mahanoy focused on a single line from the ruling, which advanced an easily digestible argument about free speech. Writing for the majority, Justice Stephen Breyer noted that, despite the vulgarity of Levy’s message, “the school itself has an interest in protecting a student’s unpopular expression, especially when the expression takes place off campus, because America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy.” Predictably, he cited Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), in which the Court affirmed students’ right to wear black armbands to protest the Vietnam War and famously declared that children do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Tinker offered a public rationale for speech: namely, that citizens benefit from a robust exchange of ideas and that the school, as an arm of government, cannot stifle political expression. In Mahanoy, Breyer went farther, claiming that criticism of the school is inseparable from its educational mission, insofar as it develops civic skills of independence and dissent.

Almost entirely unremarked, however, was the decision’s reliance on the common-law doctrine of in loco parentis, in which the school exercises disciplinary authority in place of the parent. For most of the twentieth century, common-law approaches seemed like a dead letter in education, superseded by statutory law at the state level (particularly compulsory attendance requirements, which eroded parental authority) and by equal protection rulings in federal courts (ensuring the right to private education, prohibiting racial discrimination, and applying the Bill of Rights to state governments.) Indeed, as Tinker and other decisions radically redefined school punishment in the 1970s, none of them even mentioned the doctrine. During the 1980s, however, the Court revived in loco parentis to narrow the boundaries of protected speech at school. When a teenager gave an assembly address laced with sexual innuendo, the Court affirmed the school’s right to punish disruptive speech. When another student unfurled a nonsensical banner at a school event, the court upheld his punishment, invoking in loco parentis to discourage drug use. Breyer had to acknowledge this history—and the school’s authority to punish profanity on campus—if only to limit its extension into students’ private lives.

He undoubtedly did so to secure Justice Samuel Alito’s concurring opinion, which defended Levy’s remarks almost wholly on the basis of family privacy. Alito stressed that while bad language can be rightly punished on campus, by scrutinizing a student’s actions after hours the cheerleading coach inappropriately intruded into parental responsibilities. In loco parentis predated public education, he noted, and when eighteenth-century parents hired tutors they delegated disciplinary authority on a narrowly contractual basis, limiting a teacher’s power over the child. Alito’s concurrence likewise cited Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), in which Amish families won a constitutional exemption from secondary education and (he implied) all families secured some right to educational privacy.

Missing from discussions of the Mahanoy case, however, is the tension (and perhaps incoherence) between these two positions. The private protections that Alito referenced are obviously distinct from the public benefits that Breyer invoked. And although the interests of families and individual students might sometimes align against the government (for instance, when parents and their children share the same religious beliefs), even in Yoder there was a suspicion that they might not, and that empowering parents to make decisions for their children could actually limit the children’s autonomy. In this case, while the media celebrated the stirring image of a teenager speaking truth to power, the family privacy argument at the heart of the case gave Brandi Levy no particular right to say anything at all.

The tension between children’s autonomy and parental authority is the central theme of Rita Koganzon’s recent book, Liberal States, Authoritarian Families. Koganzon points out that, like the decisions in Tinker and Mahanoy, much of today’s liberal educational theory relies on a “logic of congruence,” which assumes that democratic citizenship emerges from democratic families and schools. “Contemporary liberal theorists propose that the school and family be made to resemble the state,” she writes. “Their state is thoroughly anti-authoritarian; it denies hierarchy and maximizes equality, and so do their imagined schools and families.” But that congruence misconstrues the nature of democratic education. “The family does prepare the child for citizenship,” she continues, “but not by having him rehearse civic principles from a young age. Rather it does so by inoculating him against the worst tendencies of liberalism—the tendencies to be ruled by fashion, custom, and the opinions of the majority. The family can do this precisely because it does not resemble the state, because it is hierarchical and ‘authoritarian.’” Drawing from Hannah Arendt, Koganzon concludes that children must fall outside liberal autonomy insofar as their intellectual and moral formation requires induction into existing traditions, without which they will be vulnerable to peer pressure and unable to exercise true independence. In her words, it is only by “understanding the place of personal authority over children in the foundations of liberalism” that we can safeguard the “private or semi-private experience of personal authority, which, despite its negative associations, remains central to forming the very public life that rejects it.”

The lone dissent in Mahanoy, from Justice Clarence Thomas, demonstrates why even sympathetic jurists struggle to uphold this type of “personal authority” in public schools. Thomas noted that, in the nineteenth century, schools could punish “off-campus speech or conduct that had a proximate tendency to harm the school environment,” specifically when a student insulted his teacher. He acknowledged that compulsory attendance and rulings like Tinker might have altered this authority, but chided the majority for sidestepping the history. Yet, notably, Thomas assumed that disciplinary authority operated for the benefit of the teacher rather than the student, that punishment was a means to secure order and compliance rather than foster moral development. The same standard underlies all the case law on students’ speech rights, even Tinker. Order remains the only limiting criteria, which reduces everything to a question of institutional efficacy against individual rights and in the process leaches punishment of any educational educative value or truly moral authority.

An alternative path does appear in Thomas’s dissent—and with it a third, “semi-private” space between the family and the state—but it has remained overlooked. In a single line, Thomas pointed out that cheerleading is neither a compulsory activity nor an entitlement. Thus, “students like B. L., who are active in extracurricular programs have a greater potential, by virtue of their participation, to harm those programs. For example, a profanity-laced screed delivered on social media or at the mall has a much different effect on a football program when done by a regular student than when done by the captain of the football team.” (In other contexts, too, the Court has recognized that constitutional rights are attenuated in non-compulsory school activities.)

Extra-curricular activities incorporate elements of voluntarism and personal sacrifice. Indeed, in their pursuit of established standards of excellence, they inculcate both the “internal goods” and the virtues that Alasdair MacIntyre associates with “practices,” undertakings that he hopes will overcome the solipsistic individualism and “divided selves” of modern liberalism. In each of these respects, extracurriculars are more similar to the associational, “semi-private” spaces of civil society than to increasingly bureaucratic classrooms and governments that structure modern schooling. They are also more likely to be led and evaluated by community members than by professional educators. It is hardly coincidental that extracurriculars expanded just as secondary education became universal in the United States, or that parents and students saw them as a legitimate means of character formation just as moral instruction declined in the classroom. Despite instances of individual dissatisfaction (like Levy’s), it is in athletic contests, theater performances, and band practices that one still finds consensus around older forms of adult authority and both the implicit and explicit inculcation of moral norms.

Unfortunately, it is precisely these qualities that liberal institutions like courts cannot assess. As MacIntyre writes, “For liberal individualism a community is simply an arena in which individuals each pursue their own self-chosen conception of the good life, and political institutions exist to provide that degree of order which makes such self-determined activity possible. Government and law are, or ought to be, neutral between rival conceptions of the good life…. It is on the liberal view no part of the legitimate function of government to inculcate any one moral outlook. By contrast, on the particular ancient and medieval view which I have sketched political community not only requires the exercise of the virtues for its own sustenance, but it is one of the tasks of parental authority to make children grow up so as to be virtuous adults” (p. 195). Because they understand education in terms of adversarial rights-claims and Rawlsian notions of “public reason,” courts can approach schools as nothing more than arms of the state and thus are unable to countenance any type of moral authority in their operation.

Of course, in practice schools cannot help but impose moral norms, and the state itself depends on their cultivation. As Bryan Warnick and I have argued, legitimate forms of school punishment are far more likely to result from the creation of moral communities than from rights-claims alone. If students hope to make moral (rather than simply legal) claims against their schools, and if schools want to make moral claims on students, there needs to be a different kind of congruence between the classroom and the home, not a superficial protection of children’s autonomy but a more robust consensus around moral questions than our increasingly managerial schools have been willing to undertake. Courts can realize that vision by deferring to local decision-makers whenever possible and protecting liminal educational spaces like cheerleading teams—in MacIntyre’s words, those “local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained” between the glare of the public sphere and the particularity of the private. Preserving moral authority in schools would truly be something to cheer about.

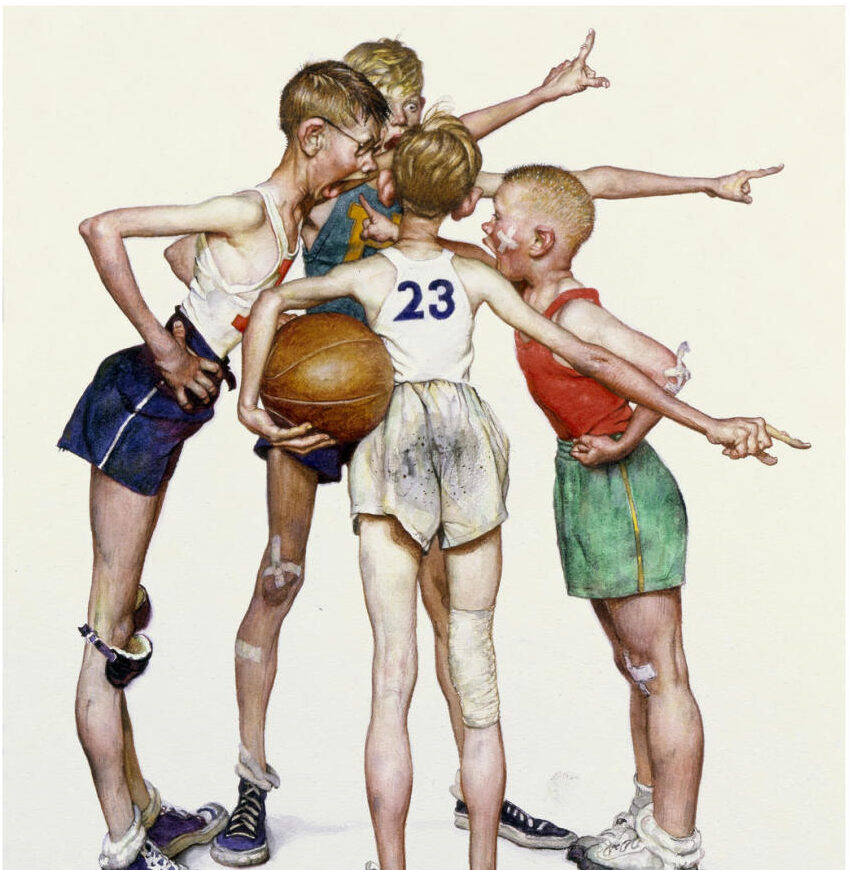

Image credit: Norman Rockwell, Four Sporting Boys: Basketball (Oh Yeah)

1 comment

Brian

In a sane world this girl’s parents would have taken away her phone, marched her to the coach’s house to apologize, the coach would have graciously accepted it with some sort of minor penalty, and we could all move on, but it’s not a sane world, and there are precious few adults left, and certainly not in today’s public education industrial complex. You can’t “preserve” that institution’s “moral authority”, as it’s long since been thrown away, to the extent that it ever existed.

I bet the ACLU doesn’t sell any shirts that say “There are two genders”, or defend kids wearing such shirts in school, do they? The fact is that organization is a fraud, as is essentially every leftist “free speech” group.

Comments are closed.